In order for society to make informed, just and equitable decisions about whether and how marine cloud brightening might be used to address climate risks in the future, we first need to understand how using MCB would affect climate locally around the globe.

Studies to assess the climate impacts of MCB use the same global-scale models currently being used to project how human activities are already affecting climate, and how climate is expected to change in the future. These same models are run, but with a given pattern of MCB implementation added, to study how climate impacts would be altered by marine cloud brightening.

How the introduction of MCB would affect future climate impacts depends both on the background climate state (most importantly, the trajectory of greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions) and on the amount and pattern of cloud brightening used. However, representing aerosol impacts on clouds in these global-scale climate models is particularly challenging because aerosol–cloud interactions depend on complex fluid dynamical and microphysical processes which occur on spatial scales much smaller than the resolution of climate models (Stevens and Feingold, 2009). Thus, we cannot exclusively rely on global climate models to tell us how much cloud brightening is possible in different locations and seasons. Modeling and observations of aerosol-cloud interactions at much smaller scales must instead be used to bound how much cloud brightening is possible, and this information used to inform the global-scale simulations of the climate impacts of cloud brightening.

Despite the uncertainties inherent in these global models’ representation of aerosol effects on clouds, early studies (e.g., Jones et al. 2009; Rasch et al. 2009; Latham et al. 2012; Stjern et al. 2018) show that MCB applied to a relatively small fraction of marine clouds (10-30%) would be able to offset a significant fraction of the greenhouse gas warming expected over the coming decades. This early work shows the potential for MCB to address the risks that come with climate warming but does not yet provide the robust information needed for decision-making.

A challenge to assessing MCB as a climate intervention has been the wide differences in global model simulations of MCB, making it difficult to determine its potential benefits and risks. These challenges result from the large range in the responses of clouds to aerosols in different models, and a lack of systematic exploration to date of the reasons for inter-model differences. The lack of an effective standard for model simulations of MCB has made it difficult for scientists to conduct comparable studies of the most prominent proposed approaches to MCB.

MCB Research Program efforts to improve understanding of the climate impacts of implementing marine cloud brightening

Building on these earlier global modeling studies and our parallel research to assess how low marine clouds respond to aerosols in likely MCB target regions, the MCB Research Program aims to improve our understanding of the potential benefits and risks of MCB through several efforts:

- Developing global modeling protocols suitable for researchers around the world to use to simulate the effects of MCB on climate in a standardized and more realistic way (e.g. Rasch et al., 2024)

Shown is the temperature response in three earth system models (CESM2, E3SMv2 and UKESM1) to implementation of marine cloud brightening in three of the five regions shown in the upper, left panel: the northeast Pacific (NEP), southeast Pacific (SEP), south Pacific (SP) and north Pacific (NP). In all three models, MCB is implemented equally in the three regions to produce a total forcing of ~1.8 W/m2. [Modified from Rasch et al., 2024]

- Leading and participating in comparisons of the climate responses across different global-scale models to similar implementations of MCB, to identify which responses appear to be robust, which are less certain, and the best next steps for reducing uncertainties

- Conducting and analyzing more sophisticated simulations designed to elucidate, for example:

- how different future emissions trajectories of both greenhouse gases and aerosols would affect the efficacy and impacts of MCB

- how accounting for the spatial variability in the concentration of sea salt aerosols injected under different MCB scenarios would affect MCB efficacy and impacts

- the mechanisms driving specific climate responses to MCB

- Identifying and improving biases and gaps in global model representation of MCB through comparisons to observations and to smaller-scale/higher-resolution simulations. In particular, assessing why clouds respond differently to aerosols in different climate models by systematically exploring the effects on cloud responses of, for example, different model capabilities and parameterizations

- Assessing the potential for MCB to address specific local or regional climate or other goals (e.g. addressing Arctic sea ice loss)

Standardized modeling protocols that can be implemented across multiple models allow for direct comparison of how different processes play out in different models, providing insights to differences in the efficacy of MCB and to potential sources of bias. Shown here are differences in how clouds respond in terms of droplet size (expressed through droplet number concentration), the amount of water in clouds, and how long clouds last (reflected by a change in cloud fraction) in two different earth system models, E3SMv2 (top row) and CESM2 (bottom row).

An overarching goal of this work is to provide researchers with more accurate analyses of how MCB might influence global and regional temperatures, precipitation, and other environmental impacts. Ultimately, this will allow us to produce more effective input to scientific assessments. We also aim to facilitate the participation of researchers from around the globe in community science efforts to assess MCB. To this end, the group is making our model output openly available for analysis by colleagues, allowing researchers from around the globe to assess, and speak directly to, how different MCB implementations would affect climate risks in their region.

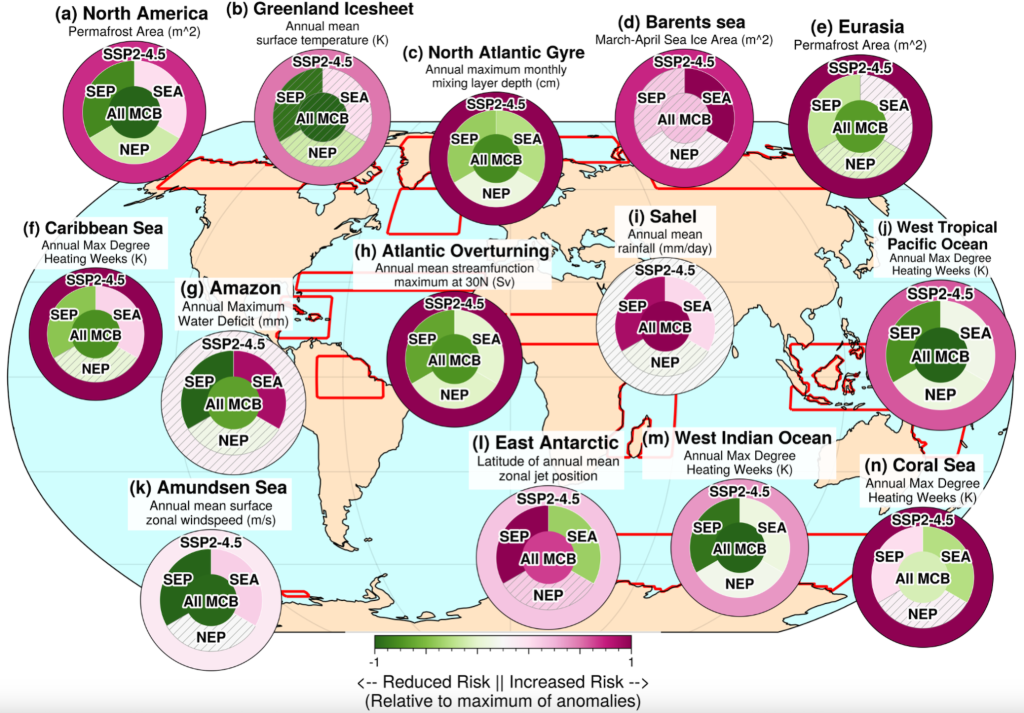

Results of an analysis to assess how different implementations of MCB would affect the chance of reaching various climate tipping points. For each tipping point, the circle shows: the risk level under a moderate greenhouse gas climate scenario (SSP2-4.5); whether that risk is increased (pinks) or reduced (green) through implementation of MCB in only one of three possible MCB target regions (the SE Pacific, SEP; SE Atlantic, SEA; and the NE Pacific, NEP); and the change in tipping point risk with implementation of MCB equally in all three regions simultaneously. [From Hirasawa et al., 2023]

Some of our recent activities include:

Development of the MCB-REG global modeling protocol

Through the SilverLining Safe Climate Research Initiative (SCRI), in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Exeter, UK and the U.S. Department of Energy Pacific Northwest National Lab, the team developed a modeling protocol, “MCB-REG”, to simulate the climate effects of implementing MCB in the three marine cloud regions considered to be the most amenable to brightening. This standardized set of simulations were run in three different climate models (Rasch et al., 2024), with several other modeling groups now in the process of using the MCB-REG protocol. The resulting body of simulations are being used to elucidate how the climate responds to MCB across different models.

Development of a G6-1.5K-MCB protocol for GeoMIP

Also through the SilverLining SCRI initiative, the team has developed a new modeling protocol that we will introduce at the 2025 meeting of the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP; May, 2025 in CapeTown S. Africa). This protocol, named G6-1.5K-MCB, is designed to be analogous to a modeling protocol developed to simulate stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) for climate cooling (Visioni et al., 2024). Both use a mid-range future greenhouse gas scenario (SSP2-4.5) as the baseline to which either SAI or MCB is introduced, and in both protocols the target is to keep global, annual average climate warming down to 1.5°C. Application of this protocol by a range of climate models will allow both comparisons across models of the climate responses to MCB and comparison of the climate responses to SAI and MCB.

Analysis to advance global model representation of processes key to determining MCB efficacy and climate impacts

The team is pursuing a number of activities to understand in more detail what drives cloud and climate responses to MCB in global models, and to assess model biases.

These include:

- Using a set of case studies to test the E3SM earth system model representation of cloud evolution against observations along trajectories in the NE Pacific that follow the transition from stratocumulus to cumulus cloud regions (Choi et al., 2024). This same set of case studies were used by our team to test higher-resolution (the SAM LES) model representation of cloud evolution (Erfani et al., 2022).

- Quantifying differences in the efficacy of MCB in different regions, in terms of both forcing per emissions and temperature response per forcing

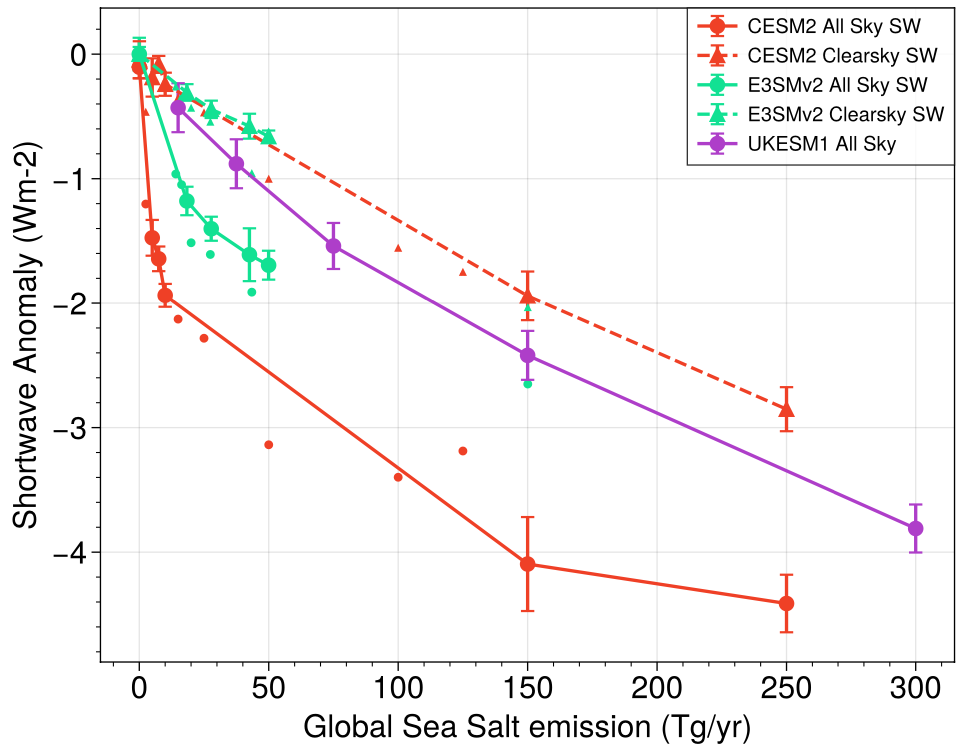

The Rasch et al. (2024) modeling protocol includes analysis of the change in shortwave forcing, which is a metric for the change in sunlight reflection, as a function of the amount of injected sea salt – revealing large differences between different models (CESM2, E3SMvs and UKESM1). [Modified from Rasch et al., 2024]

- Quantifying differences in radiative forcing per mass of injected sea salt, and diagnosing the causes of these differences, with current analyses being conducted of, for example:

- Differences across models in the amount of forcing occurring through direct light scattering by the injected sea salt vs through aerosol-cloud interactions

- Differences in the representation of the injected aerosol size across different models

- How aerosol activation into cloud droplets is affected by the use of different parameterizations in different models

Learn more:

Marine Cloud Brightening Research Program (main page)

Studies of Aerosols for Cloud-Aerosol Research

Generating Aerosols for Cloud-Aerosol Research

Governance, Engagement and CAARE

Our Team, Partners and Funders

References for this page:

Choi, K. O., P. J. Rasch, R. Wood, S. J. Doherty, 2024: Evaluation of E3SM version 2 marine boundary layer clouds over the northeast Pacific during the CSET Campaign, Journal of Geophysical Research – Atmospheres, in review.

Erfani, E., P. Blossey, R. Wood, J. Mohrmann, S. Doherty, M. Wyant, and K.-T. O, 2022: Simulating aerosol lifecycle impacts on the subtropical stratocumulus-to-cumulus transition using large eddy simulations, J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres, 127, e2022JD037258, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JD037258

Hirasawa, H., D. Hingmire, H. Singh, P. J. Rasch, and P. Mitra, 2023: Effect of regional marine cloud brightening interventions on climate tipping elements, Geophysical Research Letters, 50, e2023GL104314, https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GL104314

Odoulami, R. C., Hirasawa, H., Kouadio, K., Patel, T. D., Quagraine, K. A., Pinto, I., et al. (2024). Africa’s climate response to Marine Cloud Brightening strategies is highly sensitive to deployment region. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 129, e2024JD041070, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JD041070

Rasch, P. J., H. Hirasawa, M. Wu, S. J. Doherty, R. Wood, H. Wang, A. Jones, J. Haywood and H. Singh, 2024: A protocol for model intercomparison of impacts of Marine Cloud Brightening Climate Intervention, Geoscientific Model Development, 17, 7963–7994, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-7963-2024

Visioni, D., A. Robock, J. Haywood, M. Henry, S. Tilmes, D. G. MacMartin, B. Kravitz, S. Doherty, J. Moore, C. Lennard, S. Watanabe, H. Muri, U. Niemeier, O. Boucher, A. Syed and T. S. Egbebiyi, G6-1.5K-SAI, 2024: A new Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP) experiment integrating recent advances in solar radiation modification studies, Geoscientific Model Development., 17(7), 2583-2596, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-17-2583-2024

Jones, A., J. Haywood, and O. Boucher, 2009: Climate Impacts of Geoengineering Marine Stratocumulus Clouds.” J. Geophys. Res., 114, no. D10, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD011450

Latham, J., K. Bower, T. Choularton, H. Coe, P. Connolly, G. Cooper, T. Craft, J. Foster, A. Gadian, L. Galbraith, H. Iacovides, D. Johnson, B. Launder, B. Leslie, J. Meyer, A. Neukermans, B. Ormond, B. Parkes, P. Rasch, J. Rush, S. Salter, T. Stevenson, H. Wang, Q. Wang and R. Wood, 2012: Marine Cloud Brightening, Phil. Trans. Royal Society A, 370, no. 1974, 4217–62, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2012.0086

Rasch, P. J., J. Latham, and C.-C. Chen, 2009: Geoengineering by Cloud Seeding: Influence on Sea Ice and Climate System, Env. Res. Lett., 4, no. 4, 045112, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/4/4/045112

Stjern, C. W., H. Muri, L. Ahlm, O. Boucher, J. N. S. Cole, D. Ji, A. Jones, J. Haywood, B. Kravitz, A. Lenton, J. C. Moore, U. Niemeier, S. J. Phipps, H. Schmidt, S. Watanabe and J. E. Kristjánsson, 2018: Response to Marine Cloud Brightening in a Multi-Model Ensemble, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, no. 2, 621–34, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-621-2018