Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Makah Whaling | References

Wilma Mankiller – Healthcare for Indigenous Veterans

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Healthcare for Indigenous Veterans | References

The healthcare services provided to Native Americans by the United States government have been substandard since their inception. Indigenous veterans suffer more than any other group because of the inadequacy of the programs offered by the Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (V.A.). In 2019, Senator Tom Udall and Representative Ro Khanna introduced a bill aimed at addressing this issue. The Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act focuses on creating appropriate standard care for those who have served because the problems faced by Native American civilians are compounded by the psychological and physical trauma of military service. Lack of access, understaffed facilities, and racist bureaucracy have kept indigenous veterans from receiving the care they deserve. Considering Native Americans have historically served in the armed forces at a higher per-capita rate than any other racial group, this sort of legislation is more than overdue. Wilma Pearl Mankiller, a Cherokee chief who was heavily involved in healthcare reform, would have wholeheartedly supported this bill. She would have recognized it as a necessary step toward equal treatment under the law. However, Mankiller would have also realized that the bill does not go far enough. Its focus on urban veterans leaves out a large portion of the individuals in need of care. She knew, from personal experience, that the situation on reservations was just as dire as that in cities. Wilma Pearl Mankiller would not only have championed the Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act but would have also fought to provide the same level of care to indigenous communities in rural areas.

Udall and Khanna’s bill is intended to correct the United States’ disgraceful mismanagement of the medical needs of indigenous veterans. The legislation concentrates on the seventy percent of Native American veterans who choose to live in urban centers after their time in the military. Most of these individuals are unable to access the urban I.H.S. system because the V.A. does not reimburse them for their visits. They are forced to rely on overcrowded Veterans Affairs hospitals run and staffed by non-indigenous people. Udall stated that the bill is intended to “ensure more Native veterans have equal access to timely, culturally-competent care regardless of where they choose to live after leaving their military service.” Culturally-competent care is doubly important for veterans because they often have more complicated psychological conditions than civilian patients. This type of care incorporates the beliefs, traditions, and values of the patients’ upbringing in the healing process. Indigenous veterans, living anywhere, should receive treatment equal to that of their white counterparts. The Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act, which has been on the Senate legislative calendar for over a year, is a slow but necessary move toward improvement.

The Health Care Access bill fails to address the concerns of the thirty percent of veterans who choose to reside in rural communities. These individuals are often underserved because of geographical barriers and insufficiently staffed I.H.S. programs. In remote areas, many indigenous veterans with disabilities are unable to travel to healthcare facilitates. Neither the I.H.S. nor the V.A. provides any transit service for these people. Unlike in urban environments, public transportation is rarely an option. Understaffed facilities worsen the situation because they often lack medical professionals specialized in veteran care. In Hopi veteran Vanissa Barnes-Saucedo’s case, the “I.H.S. helped her get the medications she needed to manage her PTSD, but staff members lacked practical knowledge related to veteran-specific issues.” This struggle seems to be the converse of that faced by urban veterans who are unable to find culturally-competent care in whitewashed V.A. facilities. It is the U.S. government’s legal responsibility to ensure that all indigenous veterans receive proper care. Since Udall and Khanna’s bill only assumes part of this responsibility, it does not come close to solving the problem of substandard care.

Wilma Pearl Mankiller would have supported the Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act, despite its shortcomings, because of her personal experience with trauma and medicine. She was in a car accident in 1979, which necessitated seventeen surgeries and years of physical therapy. This experience lead her to spend much of her time as Cherokee Chief “developing a comprehensive healthcare system” for her tribe. The time she spent as a leader and lobbyist acquainted her with the racial biases in the United States’ lawmaking process that lead to the holes in Native American healthcare. She would have realized that Udall and Khanna’s bill is an attempt to help the largest, most easily accessible, portion of the community in need. Even though it does not solve the problems of all Native American veterans, it does address the concerns of thousands of disgruntled people. Mankiller would have openly acknowledged that the bill ignores far too many individuals because of their location. So much of her life was spent dealing with rural health care issues that she would not have allowed them to go unrecognized. However, this recognition would likely follow her ardent endorsement of the bill. If Wilma Mankiller were still politically active in 2019, she would have fought for the healthcare rights of indigenous veterans living in both rural and urban environments.

The goals of the 2019 Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act align with those historically supported by the late twentieth century Cherokee Chief Wilma Pearl Mankiller. Senator Udall and Representative Khanna’s bill is part of a progression toward a standardized system of appropriate care for all indigenous Veterans. Mankiller’s personal health concerns and passion for protecting indigenous peoples lead her to devote her life to a similar objective. She would have wished to include rural veterans in the legislation, but this would not have stopped her from standing behind it. Wilma Mankiller’s narrative suggests that she would have struggled unceasingly to provide proper healthcare to Native American veterans.

Hilaria Supa Huamán – Lakota Education

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Lakota Education | References

Background

Most Americans agree that obtaining a post-secondary education is essential to a brighter future. However, the Eurocentric education system of the United States has failed Native students and is not suited for their success. An important factor behind Native students not excelling in the education system is the terror and shame inflicted on Indigenous peoples, because the schooling for Native children is used as a weapon to further coerce assimilation.

One tribe in particular, the Lakota, on the Sioux reservations of the Oglala and Pine Ridge, the effects of colonization and intergenerational trauma are still prevalent today. Contributing to the high rates of incarceration, suicide and use of drugs and alcohol. Sadly, the life expectancy of Lakota men is only 48 years old. Though most of these issues are in response to the Relocation Acts the US government forced upon previous generations, where Natives were encouraged to leave their reservations and create lives in bigger cities. However, the Relocation Act possessed an unrealistic optimism and didn’t address issues like racial discrimination or segregation. This act destroyed and disrupted Native Culture, eventually leaving Natives homeless and struggling. The Relocation Act of 1956 is a major contributor to the high number of Native Americans living off the reservations.

On average, according to the Bureau of Indian Education, 90 percent of Native students attend public schools off the reservation. In these public schools, white students are twice as likely to succeed than Native students. When students lack the basic resources offered to every other community, it hinders the progress that they are able to make. When it comes to graduation, only 70 percent of the students graduate. A large number of Native students are left feeling invisible and their dream of going to college is not in the near future. Action is needed for the Lakota, because half of their population is under the age of 25 and the overall mental health of the students is declining.

Resilience

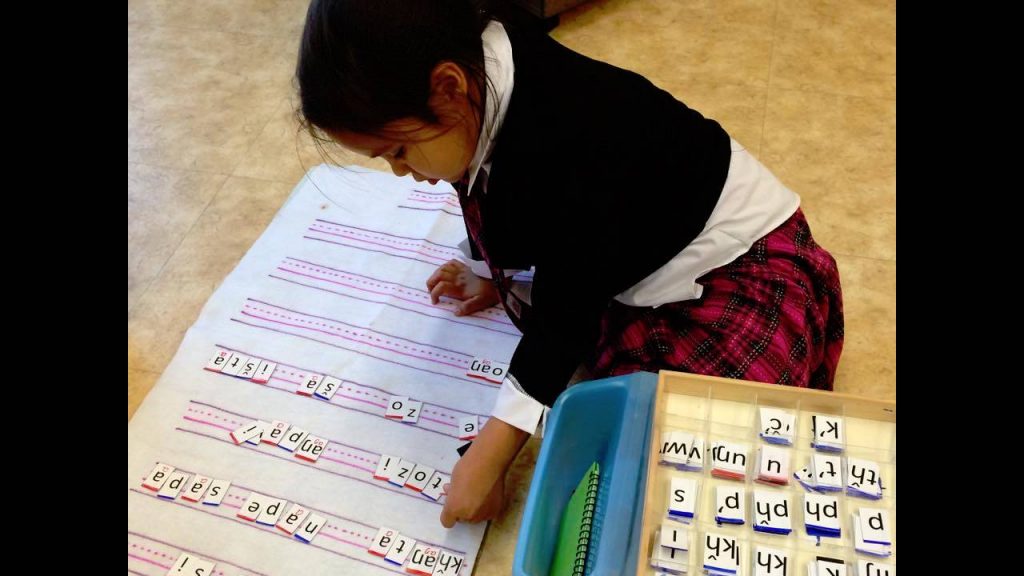

Despite these statistics, there are Lakota students who show their resilience by continuing their education. Some have been accepted into prestigious colleges like Yale University, for example. Along with the increasing numbers of teens attending college, a school called “Red Cloud Indian School” offers students an alternative option for school, focusing on the Lakota culture, teachings, and language. At Red Cloud High school, the students are required to take 4 years of Lakota language. Also, the National Indian Education Association has been able to create a plan with state education to consult with tribes on the needs of tribal students. Aside from the state education, within the public schooling, schools have been implementing and evaluating Native language immersion. NIEA has also offered schools for additional funding for drop-out prevention, and mental health services. The Lakota community approves of the immersion of culture into the schools because it offers economic and social contributions.

Hilaria’s Position

Hilaria Supa Huamán, a Quechua Peruvian activist and politician, is recognized for her part in the fight for the rights of Indigenous peoples. Being an Indigenous person, practicing her traditional ways and speaking her Native language of Quechua, she understands the importance of one’s culture. One of Hilaria’s core issues is the fight for Indigenous and peasant education rights.

Hilaria would agree that the United States school system is suited for white students to succeed, while the lack of resources for Native students keeps these communities in a vulnerable position. Vulnerability is enshrined in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia where Chief Justice John Marshall deemed Indians not as foreign nations, as previously stated in the Constitution’s Commerce Clause, but instead as “domestic dependent nations.” This kept the tribal nations dependent on the federal government. Forms of dependency are displayed in the education structure today, like the allocation of fewer funds to low socio-economic schools creating a need for more federal funding. It appears that the federal government’s intent was to create reliance by Natives, in a ward-guardian relationship, in order to maintain control over Indigenous peoples.

It appears that Hilaria would lobby for more federal funding for public schooling in the lower socio-economic Indigenous communities in order to create a more equal learning experience. For the Lakota in particular, Hilaria would emphasize the importance of integrating the traditional Lakota culture for the students and allocate funds for culturally relevant activities like after school programs but also culture programs during regular school hours. When it comes to the organization of the social structure in schools, I feel that she would assist the schools in creating models of education for the students which were not based off of the colonial mindset but rather change the focus toward a more matriarchal societal structure. She might begin an outreach program for Native girls, much like her organization FEMCA, to inform the girls about their heritage, to encourage them to learn and practice their ceremonies, and to help them understand that they are the bearers of culture. As President of the Education Commission, she worked tirelessly for the education rights of the Quechua, and she would most likely do the same for the Lakota.

Tame Wairere Iti – Tibetan Language Erasure

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Tibetan Language Erasure | References

A key feature of cultures word-wide is their ability to relay information and intergenerational knowledge through a shared common language. Not only then is the language a core identity of a culture, but it becomes attached to all elements of a people as their vocabulary shapes the way that they interact with the surrounding world and others. In models of colonialism, language is often the first and most noticeable distinction between peoples, which is why it is often the first portion of a culture that is directly targeted. Language activism is a centuries-long tradition by Indigenous peoples, tied to protecting their identities, and is still present across hundreds of international movements.

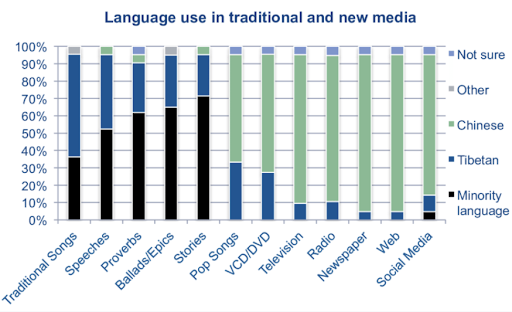

Language erasure is not only an institution of colonialism centered around dehumanizing a culture, it is additionally a deeply political process that is centered around the control of power. Following the occupation of Tibet by the Communist Chinese government in 1950, multiple policies and orders across the newly conquered state were enacted that actively discouraged the use of the Tibetan language. These laws were often indirect and subtly worded however their intended effect was wide-spread and difficult to reverse. The Chinese government used a diverse array of methods to limit the use of Tibetan, including exchanging Tibetan school books for ones provided by the government written in Chinese, changing all street signs and official documents to be only written in Chinese, prohibiting Tibetan from being used in official proceeding, and spreading a propaganda campaign that called Chinese the language of the future. It was not until the 1990’s that Tibetan activists became outspoken on the issue of language activism as it became apparent that the generation raised after Chinese occupation was more comfortable speaking Chinese than their own native language. However, as Tibetan awareness grew, the Chinese government began actively jailing and oppressing activists that sought to mobilize the populous. Even in the 21st Century little change has been realistically achieved by Tibetan demonstrations and several key leaders of the movement are currently imprisoned in China for actions taken against the authoritarian regime.

Tame Wairere Iti has experienced restrictions of his own language and been involved in language activism since he was in primary school. Iti believed that the language was a part of being Maori and didn’t understand how a person could be one without the other. The principal of his school declared that no one was allowed to speak Maori and were to only use English. Tame and his close friends chose to stand up to his principal and continued to speak Maori in school for weeks even though he was punished for standing up for his culture. From a young age, Tame has clearly understood the connection between both culture and identity with language and the importance of keeping native languages alive. For these reasons, Tame Iti would side with the Indigenous peoples of Tibet and help them attain the freedom to speak whatever language through the implementation of his unique and effective activism strategies.

Tame Wairere Iti has consistently been involved in activism for the Maori language since his youth and would undoubtedly have a strong opinion on language politics. Tame Iti sees language as an extension of self that deserves to be protected and celebrated like any other aspect of one’s culture. Although Tame Iti carries a positive view of China and Communism, as he had previously traveled there during the 1973 Cultural Revolution, he is outspoken on the topic of equal and accessible Indigenous rights to speaking a native tongue. Tame Iti would likely respond to this event by encouraging people to speak and use Tibetan whenever they could in their daily lives, as well as help to set up large scale protests. Although New Zealand’s relationship with the Indigenous Maori has been historically very different from China with Tibet, there are enough similarities that Tame Iti would likely continue to advocate in a similar manner. Tame Iti has additionally shown that he is not opposed to using force to effectively execute his plans, and thereby deliver a strong and cohesive message. However, as of now, Tame Iti has primarily retreated from the public sphere, due to his multiple arrests in the early 2000s, and is now focusing more on activism through art. It is important to note that Tame Iti would likely not want to get heavily invested in this struggle as he has repeatedly stated that while he supports other Indigenous groups, he believes that, when they can, they need to find their own path to recognition. It is for all of these reasons that Tame Iti would both fully support and recognize the Indigenous Tibetan’s continuous struggle for language recognition.

Not only is the study of the relationship between identity, language, and culture deeply personal for many individuals, it requires a reexamination of ideas of progress and prosperity. Both Tibetan and Maori activists grapple with countries that see their languages as obsolete, and with being the minority population in a land that once solely belonged to them. Tame Iti has advocated since his youth for both language recognition and Pan-Indigenous unity which is why he would undoubtedly support Tibetan resistance against Chinese policies.

Ramona Bennett – Little Shell Chippewa Tribe of Indians

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Little Shell Chippewa Recognition | References

The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians were federally recognized as the 574th Tribe in the United States December of 2019. Little Shell had been fighting for recognition since the 1930’s, making this battle almost 100 years long. Being federally recognized is such an important aspect to many Tribes and affects their sovereignty in several different ways. Becoming the 574th federally recognized Tribe opened many doors for the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians and they are now able to obtain and practice privileges the United States government promised in the treaties signed with Native Americans.

Ramona Bennett, being the woman she is and having fought the battles she has, would be very happy for the Little Shell of Chippewa Indians in our opinion. After that long of a battle, as well as having to sacrifice and feel the world around them continue to deem the lack of recognition as them being not Indian. Ramona having been a part of so many issues around Tribal policy and recognition in different fields would not only be pleased by this but also agree that the recognition process needs to change.She would say not only does the application process take years, clearly as Little Shell’s recognition shows, but the services and that many of the individuals in these Tribes need are not provided or cared for until the Tribe itself is recognized. Services such as Health care and social services for example are not governed by the tribe thus members are forced to seek help elsewhere, falling into a cycle as many western practices do not completely understand Native American circumstances, issues, or ways of going about things and so do not provide the correct services or help that the the Tribe would be able to should it have had the power and services. Most of Ramonas work was around social work, and this Tribe being able to finally have the proper services is something she would always agree with.

Ramona’s part in the historical Fish Wars of the 1970’s is why we chose this current event to focus on and discuss her response. Much like the Boldt decision finally giving recognition to the Washington state tribes and their Treaty rights, the recognition of the little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians was a long fought battle that in all honesty should have never been one. These promises and agreements made with the united states government should be upheld entirely and not taken back when they no longer profit or provide anything for the United States. Ramona would be crying happy tears and cheering loud along with all the other warriors of the Native communities, after fighting so long it seems almost normal to have to and once it’s over and you actually win there is a astounding overwhelming feeling that is not even imaginable.

As she spent many years on Tribal Council she would say, that although the fight is over the work is not done for the Little Chippewa Indians. Now that recognition has been established there is much to do around establishing themselves as a Nation, community, and people.

She would congratulate them, thank them for not giving up on themselves, and most likely give whoever she was speaking to from their Tribe a hug.

John Trudell – Oklahoma Tribal Gaming Dispute

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | OK Tribal Gaming Dispute | References

Tribal Gaming first began in the late nineteen-seventies. The initial form of tribal gaming came through bingo halls. By the mid-1980s, the United States began charitable gaming and state lotteries. Federally recognized tribes began running casinos as a form of revenue for communities. Contentions between the states and tribes questioned whether or not tribes had the authority to conduct gaming w/o state regulations.

In 1987, the court case: California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians (480 U.S 202) settled the conflict at a national level. The US Supreme Court “confirmed the inherent authority of tribal governments to establish and regulate gaming operations independent of state regulation, provided that the state in question permits some form of gaming.”

In the following year, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) of 1988. With this act, the state was given a voice in determining the scope of tribal gaming through a tribal-state compact for Class III gaming. Class II and I were to be regulated under full tribal authority. Furthermore, the National Indian Gaming Commission (NICG) was to maintain regulations at a federal level.

This was enacted in 1988 as Public Law 100-497 (25 U.S.C. 2701). Within this law, the framework for tribal gaming was established. The regulations for each class remain different. Class I gaming includes traditional Indian gaming and social gaming for minimum prizes. In class I, the regulatory authority belongs to the tribal governments. Class II gaming includes games of chance, such as bingo, pull tabs, and punch boards. This authority to license and regulate remains with the tribes, but it must be approved by the NIGC. Class III gaming is the broadest category. Class III includes all games outside of Class I and II, such as slot machines and table games. This category generates the greatest revenue and must be negotiated through state-tribe gaming compacts, approved by the Secretary of the Interior and the tribe must have their gaming ordinance approved by the NIGC.

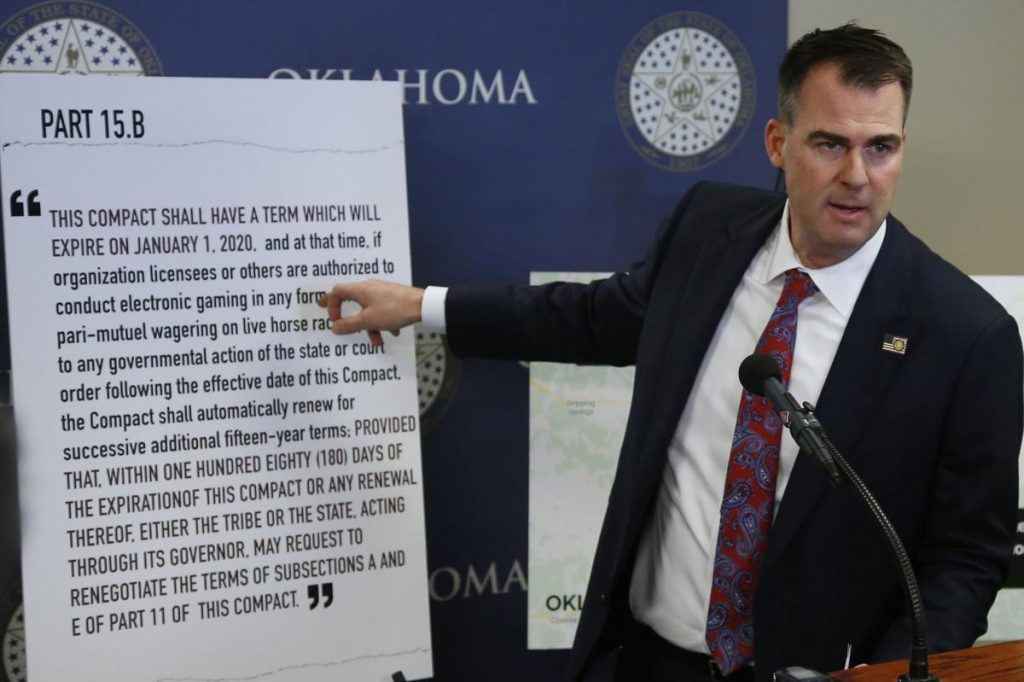

In Oklahoma, the first gaming compacts were signed in 2005. This was a 15-year compact with renewal set for January 1st, 2020. The current issue lies within the state government and their response to the Class III compact renewal. Governor Kenny Stitt(R) and the state of Oklahoma argue that it is time to renegotiate the compact. The State believes that the tribes owe greater taxes on their exclusivity fees for operating Class III gaming. Under the gaming compact, Oklahoma Tribes are required to pay an “exclusivity fee” for the exclusive right to operate Class III gaming. This form of revenue sharing is not explicitly authorized by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. Oklahoma tribes pay an average of 10-15% of their gaming revenue to the State. A recent Oklahoma Gaming Compliance report showed that the state received $1.28 billion in exclusivity fees since the Class III gaming compact was in effect. These funds have been directed to a variety of programs, most of which funds public education. Public school districts, especially rural, rely heavily on these funds.

Many tribes are in opposition of the greater taxation rates. Oklahoma Tribes argue that the compact was an agreement between equals. In order to renegotiate, both parties must be willing. Additionally, many tribes believed that this compact was set for automatic renewal. Governor Stitt has stated that the tribes must renegotiate or they will be illegally operating their casinos. Since then, the Cherokee, Chickasaw and Choctaw nations have issued a federal lawsuit on Governor Stitt. Their argument focuses on this portion of the compact: “This Compact shall have a term which will expire on January 1, 2020, and at that time, if organization licensees or others are authorized to conduct electronic gaming in any form other than pari-mutuel wagering on live horse racing pursuant to any governmental action of the state or court order following the effective date of this Compact, the Compact shall automatically renew for successive additional fifteen-year terms.” Under this, the tribes believe that the compact should renew. The state government disagrees. It will be up to the federal courts to decide. The National Congress for American Indians, the Seminoles, and Muscogee Creek Nations have vocalized their support of the lawsuit. In the meantime, Gov. Stitt recommended to place the funds in escrow until the dispute was handled. However, Mike Hunter, the Attorney General stated that this was not possible. Tribal leaders have shown willingness to negotiate, but they want the Governor to honor the automatic renewal, remain respectful on the agreements made between Tribes, and honor the sovereign rights of Tribal Nations.

Tribal gaming is one of the main sources of revenue for many federally recognized tribes. It is a critical driver of the economy because it generates 45% of all gaming revenue in the US. Since the passing of the IGRA in 1988, tribal gaming has grown from $121 million to over $32 billion in 2017. Revenue from tribal casinos provides careers, supports local businesses, and funds state, local, tribal government programs. This funding allows tribes to stimulate the economy, provide services such as housing, health care, education, and employment.

Tribal gaming provides many opportunities for improving local infrastructure. In 2017, the Oklahoma Native Impact Study reported that Oklahoma tribes are responsible for 96,177 jobs, $13 billion in annual contribution to Oklahoma economy, and $4.6 billion in wages and benefits to Oklahoma workers.

If John Trudell was alive to comment on this issue, he would say, “Our ancestors fought for the right to do whatever they so choose on their homelands and territories. Our tribal governments operate to serve the people and by demanding more from our tribes, we cannot provide for our people. The corporate greed that has permeated our state and federal government seeks to exploit our lands and bodies for profit. The very same government that occupies the lands of our peoples seeks payment for our occupation, when it is the government that should be paying for its occupancy. The rent is long overdue. The government, as an institution, operates to maintain a status quo. Those in power will remain in power while our people are perpetually subjected to economic enslavement.

These nations made an agreement and it is up to you [the state government] to uphold your end of the bargain. These nations seek to maintain a mutually beneficial relationship. If you have interests in these people, you must maintain a level of respect and integrity. By ignoring these nations, you are ignoring their rights as sovereign entities. This country was built on the backs of Indigenous peoples and it still relies on them today. This issue, for the government, is about making money. Meanwhile the issue for these nations is honoring your word. Respect and recognition sit at the center of our values. We have honored ours and we will continue to do so. It is up to you [the government] to do the same.”

Elizabeth Peratrovich – North Dakota Voting Rights

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | ND Voting Rights| References

In the last decade, North Dakota has been on the center stage when discussing Voter ID laws in the United States. In 2011 the state was accused of redistricting a legislative district to strengthen republican votes and dilute the influence of African American voters. Since this time, North Dakota has seen multiple lawsuits regarding various voting law violations. This voting injustice was made worse in 2013 when the United States supreme court voted for Shelby County v. Holder that took out a key part of the Voting Rights Act, which held certain jurisdictions with a history of discrimination accountable. These jurisdictions had to submit any proposed changes in voting procedures to the U.S. to ensure equal opportunity.

As North Dakota has faced multiple voter ID lawsuits, one in particular came from seven Native Americans: Richard Brakebill, Deloris Baker, Dorothy Herman, Della Merrick, Elvis Norquay, Ray Norquay, and Lucille Vivier. All of which had voted in the past but were denied due to the new state regulations of presenting a valid ID. Most notably was Richard Brakebill who was represented by the Native American Rights Fund (NAFR) in 2016 claiming North Dakota was disenfranchising Native American voters.

This lawsuit was grounded in the claim that these new laws excluded Indigenous votes. The new state law required all citizens to provide present identification with a residential street address, which is against state and federal law. Many reservations do not have proper identification of streets due to the state failing to assign residential street addresses. Lack of state-issued identification of reservations street addresses and restrictions by voting laws showed the state of North Dakota’s disregard for Indigenous votes. These two forces working in collaboration led to many Indigenous voters cornered and unable to cast their votes.

In 2018 NARF and Campaign Legal Center (CLC) filed separate lawsuits on behalf of the Spirit Lake Tribe. In 2019 there were 5,868 residents of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe that were affected by this new voter law which lead to them joining the Spirit Lake Tribe’s lawsuit to ensure their people were not discriminated against. In 2020 the Secretary of State has agreed to settle the voter ID lawsuit by allowing tribal ID’s to be used as proper identification. Additionally, the Secretary of State has entered a binding consent decree which guarantees that Native American voters do not need to know nor have a residential street address to be able to vote. This agreement from the Secretary of State leaves many Indigenous nations of North Dakota hopeful that their voting rights will be respected and valued.

After WWII began in 1939, many Alaskan Natives either signed up for the draft, or became a part of the Alaska National Guard. In fact, a disproportionate amount of Indigenous peoples across the United States and Canada fought alongside their respective colonizing nations in wars, even though their citizenship as Native Americans was only granted in 1924, and they were still treated as second class citizens. Seeing the valiant efforts of her Tlingit brothers in the WWII efforts sparked the unrest inside Elizabeth and Roy’s hearts upon seeing how Alaskan Natives were treated by whites in the territory. Elizabeth understood the similar feeling of Indigenous nations across North Dakota, as the United States government placed indigenous peoples in a corner where they had to compromise their rights.

This Piece was Made by Elizabeth’s eldest son to honor her as a Native American civil rights leader. She is dressed in an evening wrap as he remembers her on the night the first Anti-Discrimination Bill was passed on February 16th, 1945.

“No Natives Allowed” signs were blaringly disrespectful when many of those Native men had laid down their lives for the freedom of the United States. Voting rights for Alaskan Natives was the birth of Elizabeth’s fight against discrimination. Many Alaskan Natives were still unable to vote, years after being granted citizenship. Part of Elizabeth’s work, and the ANB and ANS work as a whole, fought against such disparities. Roy Peratrovich Jr. in the book, Fighter in Velvet Gloves, states that, “Both the ANB and the ANS worked to advance Native rights throughout Southeast Alaska and to support improvements in educational opportunities, employment, social services, health services, and housing for all Alaska Native people.” With that being said Elizabeth, if she was faced with the voter ID laws in North Dakota, would take a similar stance against those in power as she did in her time. If Elizabeth was still alive today, she would be very proud of the hard work of all of the Indigenous leaders across North Dakota as they too navigated the United States legal system and ultimately pressured the Secretary of State to grant them their rights. Just as Elizabeth is depicted on the night of her victory in the piece above, North Dakota should celebrate their victory, and acknowledge this as one step toward for Indigenous rights.

Jeanette Armstrong – Renaming Mt. Rainier

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Renaming Mt. Rainier | References

One of Washington’s most well-known landmarks is Mt. Rainier, named after Peter Rainier, a friend of the colonizer George Vancouver. In fact, the volcano is so loved that the University of Washington designed portions of its campus, the Rainier Vista, to ensure the perfect view of it.

Long before Vancouver ever laid eyes on Mt. Rainier, multiple Pacific Northwest Indigenous tribes gathered at, explored and built a relationship with the volcano. This relationship dates back to at least 5,000 BCE; while only a minuscule portion of Mt. Rainier’s area has been covered by archeologists, over 75 prehistoric sites and items have been discovered. While no singular tribe necessarily lived on the volcano, there is a multitude of tribes that visited and cherished Mt. Rainier–originally known as a variety of names, including Tahoma, Tacoma, Pooskaus, Tacobeh, or Ti’Swaq’. Puyallup activist Robert Satiacum has been fighting to get Mt. Rainier renamed to this last name, Ti’Swaq’, which translates into “the sky wiper,” or “it touches the sky.” The multitude of names reflects the multitude of languages, people, and culture that blossomed around Ti’Swaq’. “Mt. Rainier” erases the presence of the local Indigenous People and the history that they share with the volcano, and instead dishonors Ti’Swaq’ by naming it after a colonizing figure that never saw it. This incorrect name promotes a colonizing agenda that has worked for centuries to destroy Indigenous culture, heritage, and belonging to the land.

In the Syilx Nation, traditional land and water connections are embedded in their identities and local dialects. Members are raised to value the collaboration of individuals in skilled work, along with the consistent presence and respect that the Earth holds while completing their duties. As such, naming practices of landmarks are vital to Cpcaptikwlh (story-telling) because these titles encompass all of the historical, geographical, science, and cultural knowledge of the Syilx Nation. Through this, Jeanette Armstrong’s model of eco-literacy, the healthy relationship between Indigenous people and the community, land, and water, is restored. Likewise, reestablishing traditional names rejects economic colonial practices of land-ownership and exploitation. Therefore, by reestablishing Mt. Rainier to its true name, Ti’Swaq’, Armstrong’s teachings suggest that the abuses of power and miscommunication from colonizers would be reduced. This would restore Indigenous land memories, local dialects, and traditional land and water use.

In the Syilx (Nsyilxcən) language, all words and phrases have been shaped by the traditional land and water connections. Tmxʷulaxʷ (land), is a symbolic term that provides a framework to interpret the oral traditions, education, and traditional frameworks and values that govern them. Thus, also serving as the foundation for Jeanette Armstrong’s core beliefs and teachings. Similarly to the Puyallup people’s commitment to restoring Mt. Rainier to Ti’Swaq’, the Syilx Nation demanded unceded landmarks to include their traditional Indigenous names alongside their English titles.

Naramata, currently home to numerous Canadian vineyards, was originally known as citxʷs paqəlqyn or “House of the Bald Eagle”. In 2018, the Naramata Park Naming Project, after commissioning a public poll, modified all city landmark signs to include its true name, citxʷs paqəlqyn. This momentous achievement serves as a permanent acknowledgment of the colonial assimilation practices used against Indigenous peoples and their land and waterways. Moreover, with the inclusion of the Syilx (Nsyilxcən) title, Syilx people are able to reform land-based connections and begin the reconciliation process of regaining their lost language.

Another significant achievement for the Syilx Nation was permanently erecting their nation’s flag at the University of British Columbia Okanagan in September 2018. Flown alongside the Canadian flag, British Columbia flag, and the UBC flag, the Syilx Nation flag represents the University’s acknowledgment of their position on unceded traditional land and waterways. This event took place in 2018, while students, faculty members, and Syilx members witnessed. Jeanette Armstrong, as both a Syilx Member and professor at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, spoke from a unique perspective about combining western education with traditional teachings of the land and Syilx culture. With four of her students, they raised the flag and sung “We Are Beautiful”. Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, the Okanagan Nation Alliance Chairman, regarded this event as recognition of their distinct position as students and staff at the university. Presidents of the UBC was proud of having more diversity on the campus by creating tribal nation flags. Also, by having a stronger Syilx presence on campus, students who are unfamiliar with Indigenous Studies will be able to learn about colonialism and their ongoing effects through Syilx teachers, such as Armstrong. Moving forward, there will be more classes and projects about the Syilx culture offered in the Indigenous Studies program. This relates to the renaming of Mt. Rainier because the Okanagan gained recognition and partnership from the University of British Columbia.

The assimilation practices in Canada and the United States of America sought to eliminate the Indigenous peoples’ identity, by claiming ownership of the traditional lands and waters that held their languages, cultures, and traditional frameworks and values. The reclaiming of Naramata and UBCO serve as examples that reinstating traditional place-making would allow for the revitalization of Indigenous cultures. Therefore, through the understanding of Jeanette Armstrong’s eco-literacy philosophy, Mt. Rainier should be renamed to Ti’Swaq’ to properly honor the Pacific Northwest Indigenous peoples and begin the healing process.

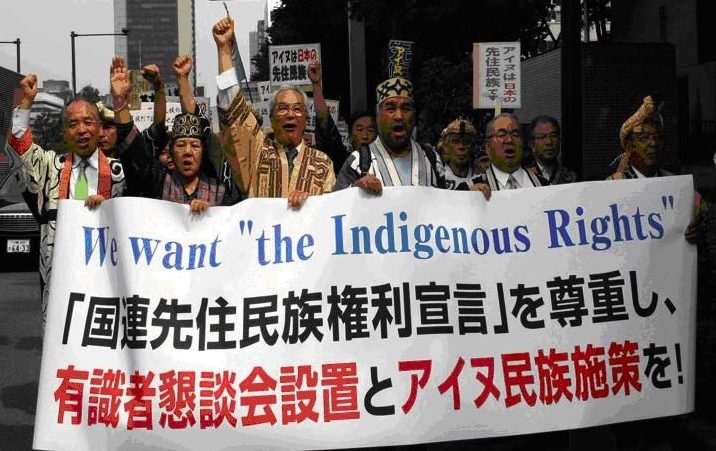

Matika Wilbur – Ainu Sovereignty

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Ainu Sovereignty | References

The Ainu people are a small Indigenous nation located in Northern Japan. For centuries the Japanese government and citizens of Japan aggressively discriminated against the Ainu people while creating policies that forced them to assimilate. In 1899, the Japanese government enacted the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act essentially creating a legal way for the government to assimilate the Ainu people into Japanese society. For nearly a century, the Ainu people were forced to leave behind their traditions and culture and instead adopt those of the Japanese. Like boarding schools across the United States forced upon Native American children, Ainu children were forced to go to Japanese schools where they were taught the Japanese language and traditions rather than their own. The Ainu language and other important cultural practices were not allowed. Despite the fact that the goal of this act was for the Ainu to assimilate into society, many Japanese people still discriminated against all Ainu people, no matter how great an effort they made to cooperate and appear more Japanese.

The Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act was finally removed in 1997 and replaced with the Ainu Cultural Promotion Law. This law worked to promote the diversity that the Ainu culture brought to Japanese society. This forced both the local and national government to make efforts to promote and protect the Ainu culture. In 2007, the United Nations also made a declaration that outlined rights of Indigenous people, which Japan chose to agree to and support. Both these acts represent the apparent support that Japan had for creating a more inclusive and diverse population. The Japanese government recognized that their economy may see improvements by creating and supporting certain polices that mitigated the discrimination against the Ainu people.

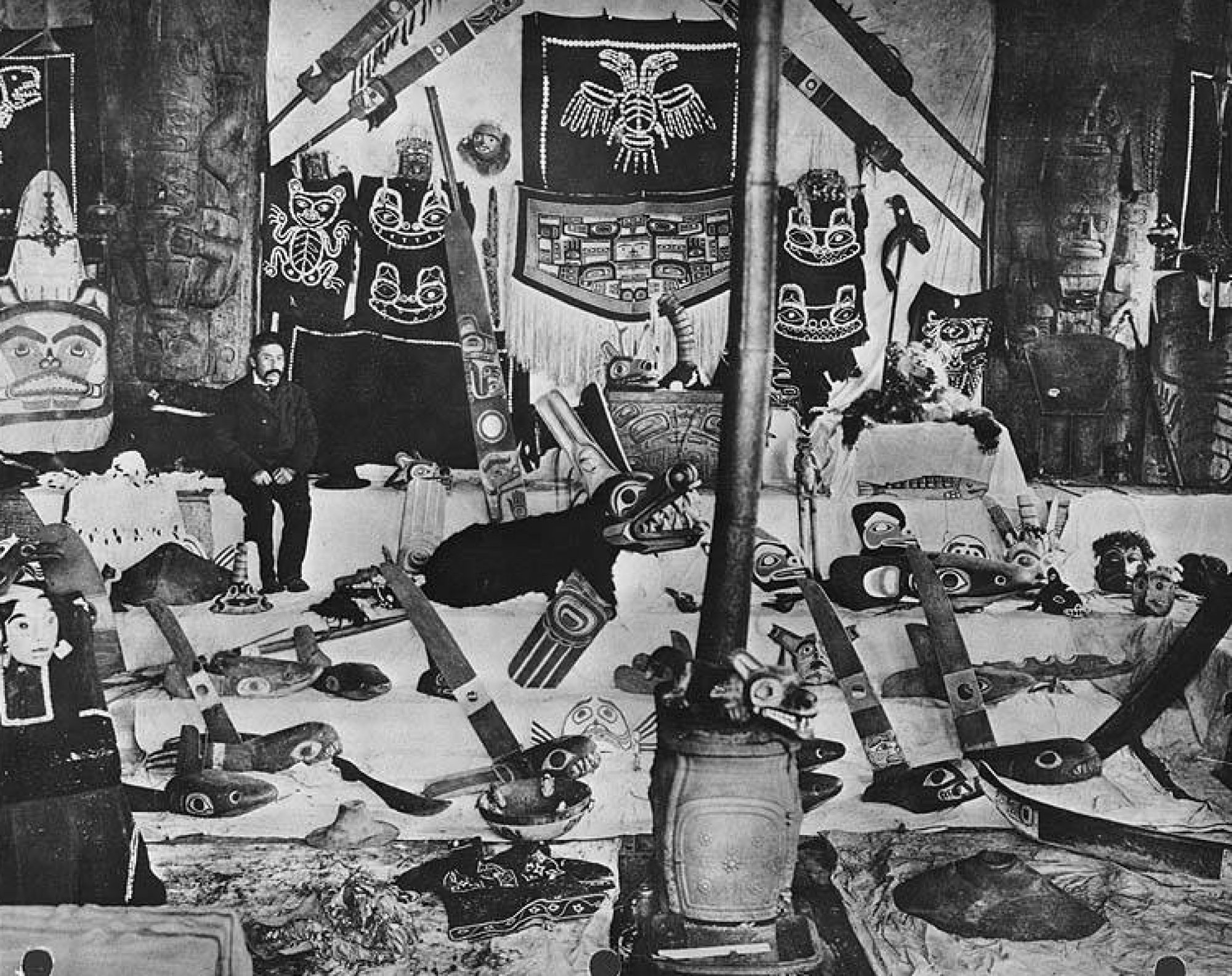

In response to the acts the Japanese government adopted in opposition to assimilation, they chose to create a museum putting the Ainu people’s culture on display for everyone to see and learn from. This action at first appeared to many to be a great act to repair the poor relationships between the Ainu and Japanese. However, many Ainu people were very unhappy and actually in opposition to the purpose in which the museum, Upopoy, was meant to serve. While the government effectively displayed the Ainu culture, they still failed to help actually create programs to that helped the Ainu people. They failed to help increase jobs for the Ainu people, so many still remained in poverty even after the museum was built. The museum failed to actually provide any help to improve the lives and ensure the futures of the Ainu culture, most notably the future of their language. Almost as importantly, the government never out-right stated that their acts of assimilation and discrimination were wrong. This failure to apologize and admit to their wrong-doing goes to show that the intentions of the Japanese government were not to actually improve the livelihood of the Ainu, but instead improve their own economy and worldly appearance.

Matika Wilbur’s work and efforts as an Indigenous activist focuses on creating a new narrative and image of what an Indigenous person looks like and is. The many photographs she has taken during her travels across the United States for Project 562 has shown the diversity of Indigenous people. The pictures show people of all ages and different genders. With each photo, she attaches a statement describing the pictured individuals, including their jobs, families, activist efforts and various other unique attributes. Wilbur clearly shows through her images how powerful native people are and how giving them their own voices relays a stronger message than having non-native individuals attempt to interpret what is being said. During a Ted Talk she spoke at, she mentioned how the media represented native Americans through characters such as Tonto played by Johnny Depp and many different adaptations of the “brave” or “savage” Indian. Wilbur wants to change this imagery to make sure Indigenous people are represented correctly.

Given Matika Wilbur’s avid pursuit for representation of Indigenous people in the United States, she would stand with the Ainu people in opposition of Upopoy. She would also oppose the actions of the Japanese government that clearly show their true negative intentions concerning the Ainu people’s future success. Wilbur’s main priority as an activist is to give the people she is supporting their own voice, rather than having the government or other majority groups speak for them. Given her clear perspective on what needs to happen in the United States with Native American representation, Matika Wilbur would fully support the Ainu’s efforts. She would completely agree that the Japanese government needs to take accountability for their prior actions while helping to support the education and job availability for the Ainu people.

Whina Cooper – N.Z. Foreshore and Seabed

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | N.Z. Foreshore and Seabed References

Our Current Event is the New Zealand Foreshore and Seabed Controversy. This controversy between the New Zealand Government and the Maori Peoples has been ongoing since 1840 when the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. In the treaty it states that the New Zealand Government owns the coastal water, the foreshore and riverbeds. Since the government did legally own the land because of this treaty, they had the authority to grant parts of the foreshore and seabed to whomever they chose. This allowed the foreshore and seabed to be used by the public from these owners.

Now the foreshore and seabed were granted to private owners who allowed the general public to fish and put their boats on the coast. What the New Zealand government forgot to recognize was the Native Maori Peoples rights and use of the land and water. The Maori fish, collect seaweed and used canoes as a form of transportation. Not only is the foreshore and seabed a piece of Maori ways of life, it is apart of their culture. The land under the water was used for canoe landing, as battlegrounds and burial grounds. The government failed to establish an agreement with the Maori and allowed others to use the land without Maori permission.

As a result, the Maori started the battle of earning rights to the foreshore and seabed that holds cultural meaning to them. In the year 1997, Maori from the Marlborough Sounds applied to the Maori Land Court for rights of foreshore and and seabed in the area as Maori customary land. The case went to Court of Appeal but prior to that, the Foreshore and Seabed Act of 2004 was passed. The act claimed that the government is the owner of the foreshore and seabed (excluding private land), the public has access to the the foreshore for recreational purposes and seabeds for navigating boats. What the act also stated was people who owned dry land next to the foreshore since 1840, can apply to the government to redress and could claim territory customary rights.

On March 4th, 2009 at the Ministerial Review Panel the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act is being reviewed. The National Party and Maori Party entered into a Relationship and Confidence and Supply Agreement in November 2008. When asked why the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed act was being reviewed the response is stated in the article, Door Open to Repeal of Foreshore and Seabed Act, “In this agreement both parties agreed to initiate a review of the Foreshore and Seabed Act as a priority. A key part of the agreement was recognition of the concerns over the current Act, and also the interests of the public in using the coastal marine area.”

Upon this Ministerial Review Panel in 2009, Prime Minister John Key announced his plans to repeal the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act. Mr Key stated these decisions, 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act would be repealed and replaced with new legislation. The foreshore and seabed currently vested in Crown ownership would be replaced by a public space incapable of being owned; Existing Maori and Pakeha private titles would continue unaffected; and Customary title and customary rights would be recognized through access to justice in a new High Court process or through direct negotiations with the Crown.

In 2011, the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act is repealed and replaced with the 2011 Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act of 2011 by the National-led government. The Crown ownership of the foreshore and seabed is replaced with a “no ownership” regime. The Iwi can apply to the court or negotiate with the government for recognition of customary rights or customary marine title over a particular area. These interests cannot prevent existing rights and uses, for example, fishing and public access. As of December 2014, seven applications for recognition and customary rights under the act have been confirmed. However; none have been confirmed as of 2014.

Our Indigenous Leader, Whina Cooper would be an active leader in this current event. Through her lifetime of protesting and marching and fighting for Maori land rights, she would be an active participant in this controversy. Her main involvement in this controversy would be staying involved in the several marches held by other Maori peoples. Just like she was quick to be apart of the Maori Land March of 1975, she would be one of the main faces of the Foreshore and Seabed marches. Upon being involved in marches, Cooper would become involved in the government and Maori party. She would be one of the Maori Natives fighting for the Foreshore and Seabed Act of 2004 to be reviewed and repealed.