Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | OK Tribal Gaming Dispute | References

Tribal Gaming first began in the late nineteen-seventies. The initial form of tribal gaming came through bingo halls. By the mid-1980s, the United States began charitable gaming and state lotteries. Federally recognized tribes began running casinos as a form of revenue for communities. Contentions between the states and tribes questioned whether or not tribes had the authority to conduct gaming w/o state regulations.

In 1987, the court case: California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians (480 U.S 202) settled the conflict at a national level. The US Supreme Court “confirmed the inherent authority of tribal governments to establish and regulate gaming operations independent of state regulation, provided that the state in question permits some form of gaming.”

In the following year, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) of 1988. With this act, the state was given a voice in determining the scope of tribal gaming through a tribal-state compact for Class III gaming. Class II and I were to be regulated under full tribal authority. Furthermore, the National Indian Gaming Commission (NICG) was to maintain regulations at a federal level.

This was enacted in 1988 as Public Law 100-497 (25 U.S.C. 2701). Within this law, the framework for tribal gaming was established. The regulations for each class remain different. Class I gaming includes traditional Indian gaming and social gaming for minimum prizes. In class I, the regulatory authority belongs to the tribal governments. Class II gaming includes games of chance, such as bingo, pull tabs, and punch boards. This authority to license and regulate remains with the tribes, but it must be approved by the NIGC. Class III gaming is the broadest category. Class III includes all games outside of Class I and II, such as slot machines and table games. This category generates the greatest revenue and must be negotiated through state-tribe gaming compacts, approved by the Secretary of the Interior and the tribe must have their gaming ordinance approved by the NIGC.

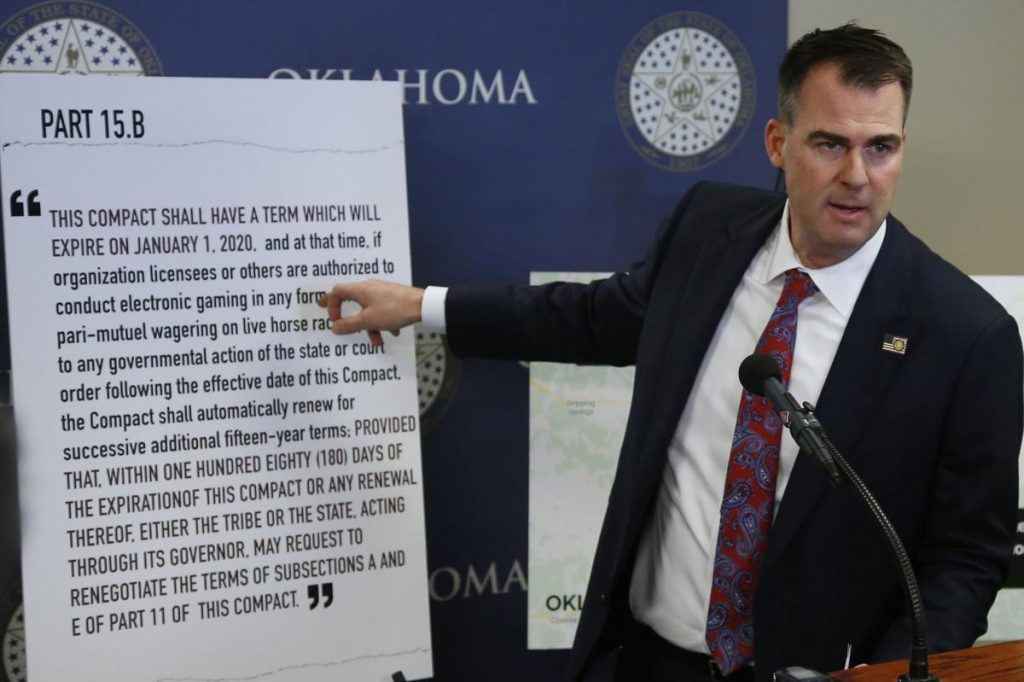

In Oklahoma, the first gaming compacts were signed in 2005. This was a 15-year compact with renewal set for January 1st, 2020. The current issue lies within the state government and their response to the Class III compact renewal. Governor Kenny Stitt(R) and the state of Oklahoma argue that it is time to renegotiate the compact. The State believes that the tribes owe greater taxes on their exclusivity fees for operating Class III gaming. Under the gaming compact, Oklahoma Tribes are required to pay an “exclusivity fee” for the exclusive right to operate Class III gaming. This form of revenue sharing is not explicitly authorized by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. Oklahoma tribes pay an average of 10-15% of their gaming revenue to the State. A recent Oklahoma Gaming Compliance report showed that the state received $1.28 billion in exclusivity fees since the Class III gaming compact was in effect. These funds have been directed to a variety of programs, most of which funds public education. Public school districts, especially rural, rely heavily on these funds.

Many tribes are in opposition of the greater taxation rates. Oklahoma Tribes argue that the compact was an agreement between equals. In order to renegotiate, both parties must be willing. Additionally, many tribes believed that this compact was set for automatic renewal. Governor Stitt has stated that the tribes must renegotiate or they will be illegally operating their casinos. Since then, the Cherokee, Chickasaw and Choctaw nations have issued a federal lawsuit on Governor Stitt. Their argument focuses on this portion of the compact: “This Compact shall have a term which will expire on January 1, 2020, and at that time, if organization licensees or others are authorized to conduct electronic gaming in any form other than pari-mutuel wagering on live horse racing pursuant to any governmental action of the state or court order following the effective date of this Compact, the Compact shall automatically renew for successive additional fifteen-year terms.” Under this, the tribes believe that the compact should renew. The state government disagrees. It will be up to the federal courts to decide. The National Congress for American Indians, the Seminoles, and Muscogee Creek Nations have vocalized their support of the lawsuit. In the meantime, Gov. Stitt recommended to place the funds in escrow until the dispute was handled. However, Mike Hunter, the Attorney General stated that this was not possible. Tribal leaders have shown willingness to negotiate, but they want the Governor to honor the automatic renewal, remain respectful on the agreements made between Tribes, and honor the sovereign rights of Tribal Nations.

Tribal gaming is one of the main sources of revenue for many federally recognized tribes. It is a critical driver of the economy because it generates 45% of all gaming revenue in the US. Since the passing of the IGRA in 1988, tribal gaming has grown from $121 million to over $32 billion in 2017. Revenue from tribal casinos provides careers, supports local businesses, and funds state, local, tribal government programs. This funding allows tribes to stimulate the economy, provide services such as housing, health care, education, and employment.

Tribal gaming provides many opportunities for improving local infrastructure. In 2017, the Oklahoma Native Impact Study reported that Oklahoma tribes are responsible for 96,177 jobs, $13 billion in annual contribution to Oklahoma economy, and $4.6 billion in wages and benefits to Oklahoma workers.

If John Trudell was alive to comment on this issue, he would say, “Our ancestors fought for the right to do whatever they so choose on their homelands and territories. Our tribal governments operate to serve the people and by demanding more from our tribes, we cannot provide for our people. The corporate greed that has permeated our state and federal government seeks to exploit our lands and bodies for profit. The very same government that occupies the lands of our peoples seeks payment for our occupation, when it is the government that should be paying for its occupancy. The rent is long overdue. The government, as an institution, operates to maintain a status quo. Those in power will remain in power while our people are perpetually subjected to economic enslavement.

These nations made an agreement and it is up to you [the state government] to uphold your end of the bargain. These nations seek to maintain a mutually beneficial relationship. If you have interests in these people, you must maintain a level of respect and integrity. By ignoring these nations, you are ignoring their rights as sovereign entities. This country was built on the backs of Indigenous peoples and it still relies on them today. This issue, for the government, is about making money. Meanwhile the issue for these nations is honoring your word. Respect and recognition sit at the center of our values. We have honored ours and we will continue to do so. It is up to you [the government] to do the same.”