Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Healthcare for Indigenous Veterans | References

Compassionate

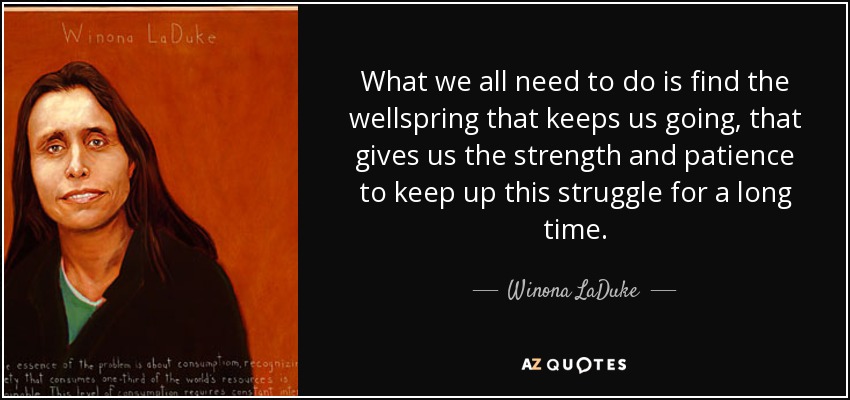

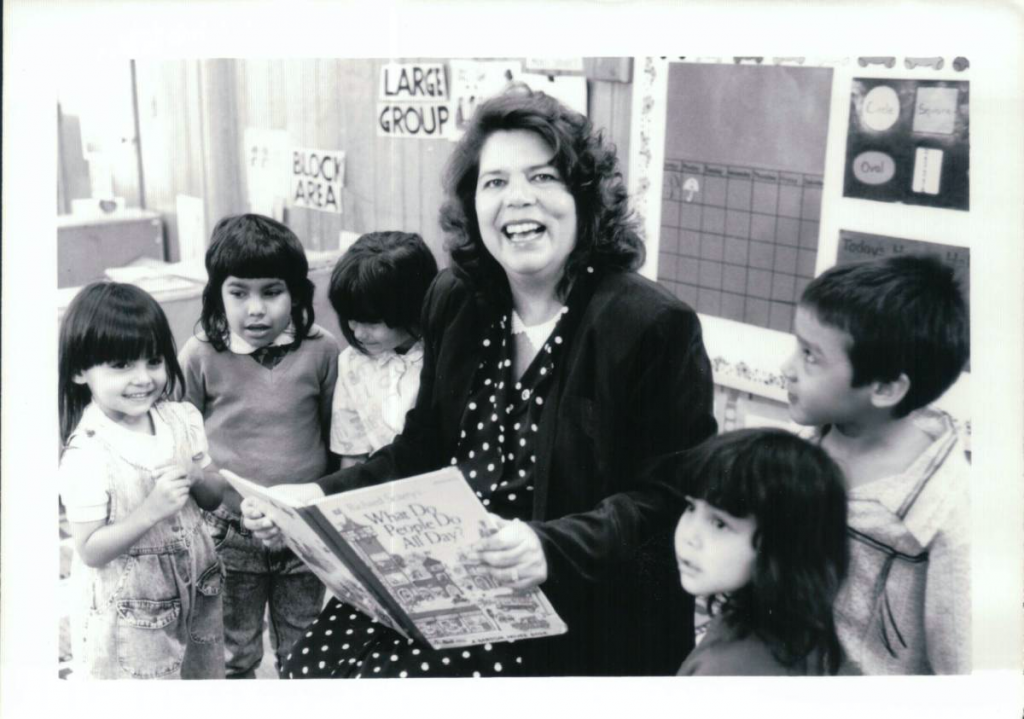

Wilma Mankiller can be most defined as being compassionate, towards her people and towards herself. She easily could have been another community member but she preferred to handle the issues her tribe was facing. Being the selfless individual she was, Mankiller’s activism involved leading some campaigns for Head Start that is a program for low-income preschool children whose goal is to provide educational, social and health needs where these families lack access. Mankiller’s concern for the next generation shows her care to ensure others are being given the same education regardless of their background. Her compassion lived through her vision most of all. She founded the community development department for the Cherokee nation and became the director. Mankiller helped establish rural water systems and rehabilitate housing for her tribe. This success of putting forth all her effort for her people was seen by the Cherokee people’s principal chief where he chose her as a running mate in the next election. Soon after she became the principal chief and created revenue for her tribe that was used for health care and job training, as well as Head Start programs. All of her energy was used to aid her people young and old. In essence, if it was not for her compassionate spirit Mankiller embodied, the platform she created would not have prospered and many of the events she evolved would not have flourished the way they did.

Resilient

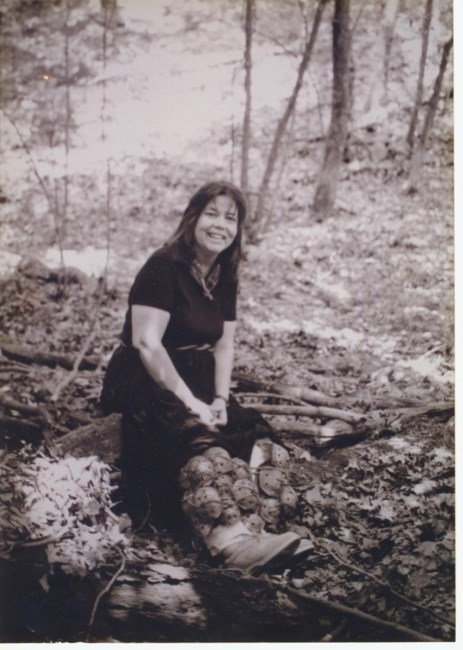

Throughout her life, Wilma Mankiller has had to face a number of challenges that has prompted her to become the resilient leader she is known to be. From an early age, her family had to relocate to San Francisco where they struggled financially. As she attended college, she became pregnant and had to resume her studies years after. These unexpected difficulties of juggling between her family and school work revealed early on the strength Mankiller carried as she navigated her path as a young adult. Her resilient energy carried as she settled through her divorce and moved alongside her children back to her tribal land in Oklahoma. It was these life turning points Mankiller heavily learned how to overcome any obstacle. As a single mother, she took on being the tribal planner until she faced another scarring challenge when she was involved in a tragic car accident where she lost her best friend. Mankiller’s spirit continued to fight through surgeries eventually leading to better health. Adapting to sudden life events, Mankiller remained persistent to keep going, she became deputy chief then tribal principal chief after winning two elections. As a leader, Mankiller gained her resilience as she never quit despite all the hardships that attempted to push her back down along the way.

”Keeper of the Village”

Wilma Mankiller’s last name from Cherokee history means “keeper of the village”. Essentially meaning a person who watches over the people. Mankiller’s leadership has earned her the qualifications under this name as she noted during her commencement speech at Northern Arizona University. Although the “keeper of the village” is honored as being the one to overlook the community, Mankiller directed her hopes towards the individuals within the community to take a stance together to make change. Her leadership style was not about one person leading the group but for everyone to be involved in public service if reshaping society was desired. Instead of waiting around, she emphasized the importance that making waves was about going forth and doing it yourself. In order to implement these ideas of going after what you wish to see onto her people, Mankiller became the first female executive on the Cherokee board. During times where females lacked representation anywhere. Her goal as she first accepted a job in tribal government was to reassure herself and others that her own community had the ability to defeat their own problems tackling issues head on such as creating programs to increase revenue for her tribe. This was all while she was still in the community developer position prior to her time as deputy and tribal principal chief. Mankiller established the meaning behind her name early on in her career as she made the moves to take initiative directly.