Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Fishing Rights in Alaska | References

In October 2012, fishing on the Kuskokwim River in Southwest Alaska was closed due to low amounts of king salmon during a salmon run. Native fishermen who depend on salmon, decided to ignore the closure because they believed their rights surpassed the state’s decision to close the river. Alaska State Troopers were notified of the defiant act and descended upon the river, apprehended dozens of nets, and more than 1,000 pounds of fish. The state pressed charges against sixty-one fishermen. This event sparred a rally, not the first rally for fishing rights, and certainly not the last. Alaskans gathered together to demand indigenous fishing and hunting rights be restored. These rights were eliminated under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971 and since then, Alaska natives often find themselves in a losing battle of rules, regulations, and jurisdiction. In 1980, congress attempted to fix this by enacting the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). In theory, ANILCA was meant to help Alaska Natives by allowing subsistence hunting. However, ANILCA also allowed any rural resident to engage in subsistence hunting if they could prove residency in Alaska for one year. Subsistence fishing and hunting has been a continuing concern for Alaska’s Natives with no end in sight.

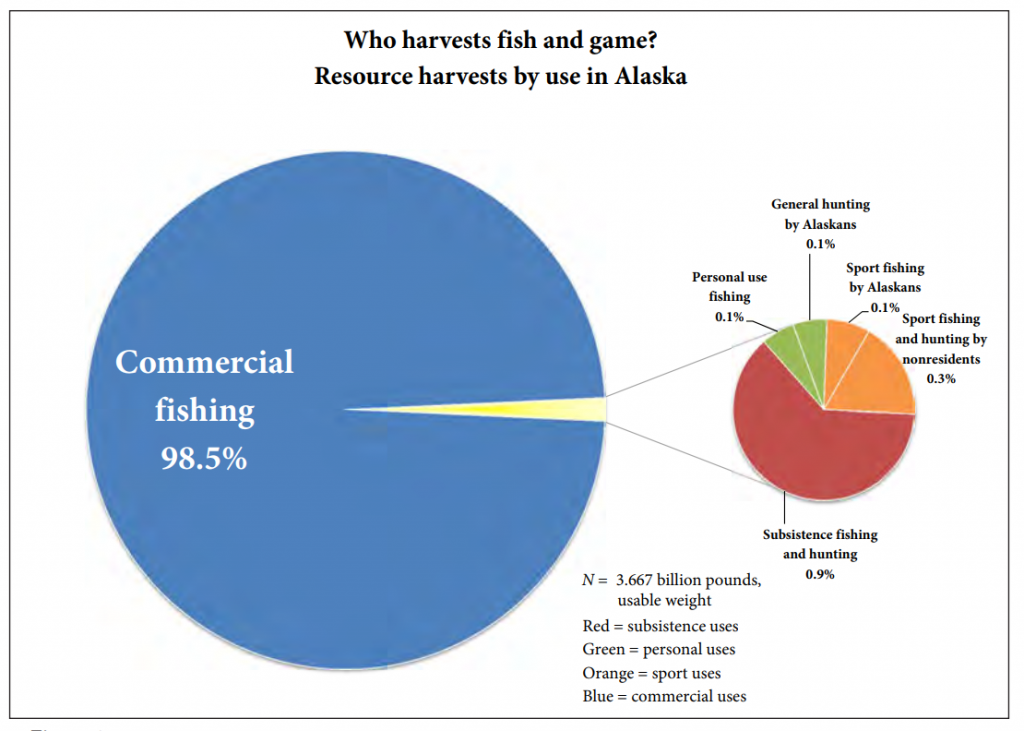

In 1971, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act attempted to resolve land claims of Alaska’s Natives. This act gave the legal title of forty-four million acres of land to Alaska’s Natives if it was considered unappropriated and unreserved. Alaska’s Natives were also awarded a $962.5 million settlement. The Settlement Act allowed the development of regional, and smaller village corporations in which all Natives were eligible to be shareholders. These corporations were under Alaska state law and there were no restrictions on using or selling the land. In the continental United States, almost all Native lands are owned by the federal government and cannot be used without the consent of the United States. Because of this difference between Alaska and the continental United States, the Alaska’s Natives’ land is not considered Indian Country and the Natives do not have governmental powers over them. Aboriginal hunting and fishing rights were exterminated despite that subsistence hunting takes less than one percent of the resources. Alaska Natives are required to comply with state laws everywhere in the state. These laws interfere with Alaska Natives’ traditional ways of life and began a lengthy battle for Natives rights.

Some success was meant to come in 1980 when the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act was enacted. The ANILCA is a piece of federal legislation providing protection to millions of acres of land in Alaska. Under this act the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was implemented more specifically. The ANILCA specifies the designation of wilderness and subsistence management. Since ANILCA, Alaska Natives have practiced subsistence fishing just as they have for hundreds of years. However, Alaska Natives face the frustrating reality that their rights have been restricted. State and federal management of fish and game conflict at times and Alaska Natives become the victim of a diverging government.

Were Billy Frank, Jr. alive today, he would have stood with Alaska Natives in preserving their right to continue subsistence hunting and fishing without regulations from the government. Billy Frank, Jr. was a passionate, and resilient leader. He cared deeply for the preservation of his home, traditions, and people. If Billy Frank, Jr. would have been present in October 2012, it can be speculated that he would continue subsistence fishing despite facing charges from the state government. This assumption comes from the dozens of time Billy Frank, Jr. was arrested for fishing when the government had placed regulations that he did not believe were fair or just. Billy Frank, Jr. believed he had a right to live off the land as his ancestors had for hundreds of years. He trusted that being consistent and resilient would serve his purpose and bring attention to the overlooked travesty of indigenous peoples’ rights.

As an inspirational leader, Billy Frank, Jr. would have done more than just participated in fishing. At his core, he was an activist. He spent his entire life fighting for the rights of indigenous people and held many influential positions including chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission. Billy Frank, Jr. was defiant, but he was not brash. His actions had thoughtful and strategic purpose. He would have taken time to completely understand the situation and then determined practical solutions. As a reasonable man, Billy Frank, Jr. would have actively sought influential people in government to help his cause. This assumption comes from the video clip, below. In this clip, he speaks about “going together” to the government. It was not fair to let the united states congress, or state legislature dictate the rights of indigenous people without the opinions of indigenous people. Billy Frank, Jr. had a deep understanding that solutions are created from fair representation and compromise between parties and he would have continuously fought for the Alaska Natives’ right to fish.