Neuroscience For Kids

Tumor Paint

By Hillary Lauren, Neuroscience for Kids Guest Writer

December 18, 2013

Dr. Jim Olson, a physician at Seattle Children's Hospital and research

scientist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, likes to share

stories of the patients and people in his life who provide a motivation

for his research about brain tumor treatments.

Dr. Jim Olson, a physician at Seattle Children's Hospital and research

scientist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, likes to share

stories of the patients and people in his life who provide a motivation

for his research about brain tumor treatments.

At a recent Town Hall presentation, Olson shared a recent experience about his own mother, who was receiving radiation treatment for a cancer at the base of her brain. The physicians were attaching a metal frame the size of a football helmet to her head "the same way you would attach a Christmas tree stand to your Christmas tree," by turning screws on the frame until they touched her skull and stuck. As Olson was observing this, he thought,

You know, the way that we treat cancer patients today is barbaric. This is cutting edge, this is the leading edge of the best in the world, and we're still frying cancer, we're still putting poisons into people's bloodstream.

In his own practice, Olson is all too familiar with the challenges of curing brain cancer. In addition to radiation and chemotherapy treatments, brain cancer is commonly treated with surgery to remove malignant tumors. Surgery is extremely difficult because the work must be very exact. Leave some of the tumor behind, and the cancer can return; cut too far, and damage to the brain may cause devastating effects to the patient. Surgeons rely on cues like color, texture, and blood supply to identify the tumor, but often times the cancerous tissue looks identical to the healthy tissue.

Wouldn't it be easier if there was a way that the brain tumor could "light up," so surgeons could tell exactly where to cut?

With hard work and a lot of support from the community, Olson and his colleagues have been trying to answer this question. In a pursuit that could forever change how brain surgery is performed, Olson's team has engineered a new molecule called "tumor paint."

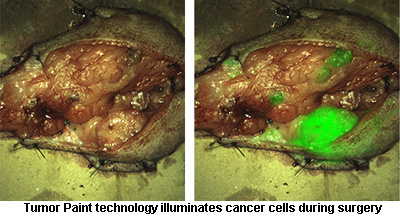

Tumor paint is a molecule that enters cancerous cells and lights up, giving surgeons a much better way to distinguish the location of the tumor.

How did Olson's team create tumor paint? First, they looked for a

molecule that would be able to find cancer in the brain. This is

challenging because the brain is naturally protected by the blood brain barrier, a special layer of tissue that

prevents most chemicals in the blood from affecting the brain. Molecules

that are able to cross this barrier and encounter a tumor are rare.

How did Olson's team create tumor paint? First, they looked for a

molecule that would be able to find cancer in the brain. This is

challenging because the brain is naturally protected by the blood brain barrier, a special layer of tissue that

prevents most chemicals in the blood from affecting the brain. Molecules

that are able to cross this barrier and encounter a tumor are rare.

The team looked through scientific research publications and considered thousands of candidates that might be useful. Finally, they found a peptide (miniprotein) called chlorotoxin, which is present in the venom of the Deathstalker scorpion (Leiurus quinquestriatus).

A researcher at the University of Alabama had been studying how chlorotoxin peptides have a high affinity for a certain kind of chloride ion channel. These ion channels are present on the surface of cancerous brain cells but not healthy brain cells.

Olson and his team tested chlorotoxin right away to see if it would uniquely light up tumor cells and not healthy cells. They attached a little "molecular flashlight" to the chlorotoxin peptide and injected it into a mouse with a brain tumor:

I told [my colleague], "If the cancer lights up, we keep going, and if it doesn't light up, we go back to the drawing board." ...An hour later, the cancer was glowing brightly, and the rest of the mouse was not glowing. I've never had that happen, where an experiment worked for the first time that I did it.

Olson borrowed mice with different types of cancers, like skin, breast, and prostate cancer, and injected them with the chlorotoxin conjugate. All the tumors lit up, just like the brain cancer. "Tumor paint" was born.

Although there are still several hurdles to pass before tumor paint can be used in treatment on humans, Olson is optimistic that in ten years, surgeons will wonder how they ever managed to do surgery without aids like tumor paint.

Using knowledge he gained from engineering tumor paint, Olson has also started Project Violet, named after an inspirational young girl who had a very serious, untreatable brain cancer. Olson hopes that other peptides similar to chlorotoxin can be used to create better, safer treatments for patients and children with brain tumors.

References and further information:

- "Tumor Paint" photo courtesy of Blaze Bioscience

- Olson, Jim. (5 December 2013). "Lighting up brain cancer." Seattle Science Lectures. Lecture conducted from Town Hall, Seattle.

- Chudler, Eric. (1996). "The Blood Brain Barrier ('Keep Out')." Neuroscience for Kids. Retrieved 8 December 2013 from http://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/bbb.html

- Lobos, Ignacio. (2007). "Buck Rogers and the amazing death stalker scorpion." Quest Online (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center). Retrieved 8 December 2013 from http://quest.fhcrc.org/.

- Wilson, Jacque. (15 November 2013). "Tumor paint: Changing the way surgeons fight cancer." CNN Health. Retrieved 8 December 2013 from http://www.cnn.com/.

- "Deathstalker." (26 November 2013). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved 10 December 2013 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deathstalker.

- "Chlorotoxin." (23 October 2013). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved 10 December 2013 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chlorotoxin.

Copyright © 1996-2013, Eric H. Chudler, University of Washington