Neuroscience For Kids

How do Parasites Hijack their Host's Brains?

The Neuroscience of Toxoplasmosis

By Kristin Harper, Neuroscience for Kids Guest Writer

October 11, 2013

A dog with rabies suddenly feels the urge to bite other animals, passing

along a virus in the process. A cricket infected with a horsehair worm

will seek out water and drown itself, ensuring that its unwanted passenger

gets the chance to mate. And when a parasitic ant fungus is ready to

release its spores, it somehow convinces its tiny insect host to climb a

plant and bite the underside of a leaf. The ant dies, fungal fruiting

bodies emerge from its body, and the cycle of life continues for the

fungus.

A dog with rabies suddenly feels the urge to bite other animals, passing

along a virus in the process. A cricket infected with a horsehair worm

will seek out water and drown itself, ensuring that its unwanted passenger

gets the chance to mate. And when a parasitic ant fungus is ready to

release its spores, it somehow convinces its tiny insect host to climb a

plant and bite the underside of a leaf. The ant dies, fungal fruiting

bodies emerge from its body, and the cycle of life continues for the

fungus.

How can we explain these strange behaviors? Evolution has ensured that viruses, bacteria, and parasites have perfected the art of infection-even changing the way their hosts behave to ensure that they, the infectious hitchhikers, are able to reproduce. This is called "behavioral manipulation," and in most cases, scientists know very little about how a pathogen affects its host's brain, forcing it to do such odd things.

Toxoplasmosis gondii: A cat-and-mouse parasite

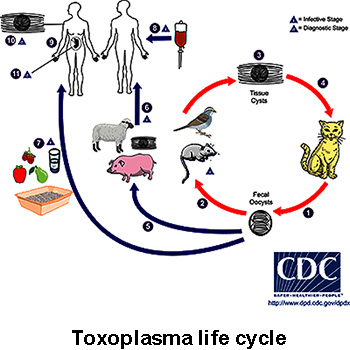

Recently, researchers have begun to uncover the pathways through which a parasitic protozoan called Toxoplasmosis gondii can alter behavior. T. gondii causes the disease toxoplasmosis in humans, but its primary host is the cat. Cats typically get infected by eating rodents infected with T. gondii. The rodents become infected after eating food contaminated by the feces of infected cats. In order to keep the wheel of transmission rolling, T. gondii forces its unlucky rodent hosts to do things they would normally find terrifying. For example, mice and rats typically avoid the smell of cat urine. This makes perfect sense-it helps them avoid cats, their natural predator. When these animals become infected with T. gondii, though, they suddenly become attracted to the smell of cat urine! This works out very well for the parasite, because once a cat catches and eats an infected rodent, the next generation of T. gondii can be produced.

How does Toxoplasma make the smell of cat urine appealing?

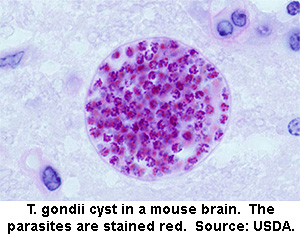

After infecting its rodent host for a few weeks, the parasite forms cysts in the animal's brain. These cysts display a slight preference for the limbic system regions, the areas of the brain that govern both predator avoidance and attraction to the opposite sex. The pathways in the brain that help control these two behaviors are separate, but they lie very close to one another, running in parallel through the medial amygdala and hypothalamus.

When an infected rat is exposed to cat urine, studies show that neural

activity shifts from the animal's predator avoidance pathway to the nearby

attraction pathway. This pathway mismatch leads an infected rat to become

aroused, causing it to spend a lot of time around the scent of cat urine

instead of being repelled by the dangerous odor. In this case, evolution

has hit upon an ingenious way for T. gondii to exploit the rat's

brain circuitry.

When an infected rat is exposed to cat urine, studies show that neural

activity shifts from the animal's predator avoidance pathway to the nearby

attraction pathway. This pathway mismatch leads an infected rat to become

aroused, causing it to spend a lot of time around the scent of cat urine

instead of being repelled by the dangerous odor. In this case, evolution

has hit upon an ingenious way for T. gondii to exploit the rat's

brain circuitry.

Female rats are more attracted to infected males

Normally, female rats try to choose mates that are parasite-free. In the case of T. gondii, this makes a lot of sense for two reasons. First, because T. gondii is transmitted between rats during mating, a female that rejects infected males can avoid infection herself. Second, a parasite-free father is more likely to sire parasite-free offspring who can avoid fates like the one described above.

But what would happen if female rats consistently rejected T. gondii-infected males? Infection levels would drop, and over time rats would become more and more resistant to the parasite. This would be bad news for T. gondii. But the parasite appears to have taken care of this threat by manipulating the way female rats choose their mates. Instead of repulsing choosy females, males infected with T. gondii become more attractive.

Even the scent of an infected male's soiled bedding is more appealing to females than the scent of an uninfected male's bedding. It appears that the parasite is somehow capitalizing on the role that scent plays in attraction. The specific mechanism by which T. gondii dupes females into falling for parasitized partners remains unknown.

Humans get toxoplasmosis too

It is not just cats and rats that need to worry about T. gondii. Humans can become infected by eating contaminated meat or via contact with feces from an infected cat. T. gondii is dangerous to babies before they are born, too. That is why pregnant women are told not to clean out the cat litter box at home! Roughly 30% of the world's population carries the parasite. That's one out of every three people worldwide. An infected mom can pass the infection on to her baby who may develop serious symptoms later.

Some researchers have become convinced that T. gondii manipulates our behavior as well. Some odd findings have been reported:

- People with latent toxoplasmosis (those who are not showing symptoms but carry the parasite) are more likely to get in traffic accidents.

- Infected women are more likely to attempt suicide.

- Infected men find the smell of cat urine more attractive.

- People who have schizophrenia are more likely to be infected with toxoplasmosis than those who do not. This has led some scientists to believe the parasite may be an important risk factor for this mental illness.

Is the parasite controlling our behavior, just as it

controls that of rats? It is unclear what the mechanism is behind all of

these odd behaviors, but some scientists believe an increase in levels of

dopamine (a neurotransmitter) may be the cause. Why? It turns out that the

brains of T. gondii-infected mice have elevated levels of this

chemical, and dopamine is also believed to play an important role in

schizophrenia. Future studies should clarify just how much toxoplasmosis

influences our behavior as well as which changes in the brain are

responsible.

Is the parasite controlling our behavior, just as it

controls that of rats? It is unclear what the mechanism is behind all of

these odd behaviors, but some scientists believe an increase in levels of

dopamine (a neurotransmitter) may be the cause. Why? It turns out that the

brains of T. gondii-infected mice have elevated levels of this

chemical, and dopamine is also believed to play an important role in

schizophrenia. Future studies should clarify just how much toxoplasmosis

influences our behavior as well as which changes in the brain are

responsible.

Research on how the infection affects mice and rats, while interesting in its own right, may provide valuable insights into the mechanisms at work in humans as well. Someday, we may even be able to exploit the information we learn about how this parasite manipulates its hosts' brains to deliver new treatments to patients suffering from brain-based disorders.

Did you know?

Toxoplasmosis is considered to be a leading cause of death attributed to foodborne illness in the United States. Symptoms of toxoplasmosis include flu-like symptoms: fever, tiredness, sore muscle, sore throat, and headaches. The parasite can cause the tissue in the intestine and lymph nodes to die. Other body parts can be affected, too, such as the eye, heart, and adrenal glands. Dehydration, coma, and death may even occur. Additionally, if a person's immune system is not strong, meningitis, an infection of the brain, can occur. More than 60 million men, women, and children in the U.S. carry the Toxoplasma parasite, but very few have symptoms because the immune system usually keeps the parasite from causing illness. (Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/)

References and further information:

- Arling, T.A., Yolken, R.H., Lapidus, M., Langenberg, P., Dickerson, F.B., Zimmerman, S.A., Balis, T., Cabassa, J.A., Scrandis, D.A., Tonelli, L.H., Postolache, T.T. Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers and history of suicide attempts in patients with recurrent mood disorders. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 2009, iii-x(12): 905-908.

- Dass, S.A.H., Vasudevan, A., Dutta, D., Soh, L.J.T., Sapolsky, R.M., Vyas, A. Protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii manipulates mate choice in rats by enhancing attractiveness of males. PLoS One, 2011, 6(11): e27229.

- Flegr, J. How and why Toxoplasma makes us crazy. Trends in Parasitology, 2013, 29(4): 156-163.

- Flegr, J., Havlcek, J., Kodym, P., Maly, M., Smahel, Z. Increased risk of traffic accidents in subjects with latent toxoplasmosis: a retrospective case-control study. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2002, 2:11.

- Flegr, J., Lenochov, P., Hodny, Z., Vondrov, M. Fatal attraction phenomenon in humans-Cat odour attractiveness increased for Toxoplasma-infected men while decreases for infected women. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2011, 5(11): e1389.

- House, P.K., Vyas, A., Sapolsky, R.M. Predator cat odors activate sexual arousal pathways in brains of Toxoplasma gondii infected rats. PLOS One, 2011, 6(8): e23277.

- Torrey, E.F., Bartko, J.J., Lun, Z.R., Yolken, R.H. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2007, 33(3): 729-736.

- Vyas, A., Kim S.K., Giacomini, N., Boothroyd, J.C., Sapolsky, R.M. Behavioral changes induced by Toxoplasma infection of rodents are highly specific to aversion of cat odors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2007, 104(15): 6442-6447.

Kristin Harper is a freelance science writer and editor based in New York. She has a Master's degree in Public Health (MPH) in Global Epidemiology and a PhD in Population Biology, Ecology, and Evolution. She has always been interested in psychiatric disorders and the evolution of pathogens, so she is fascinated by conditions, like Toxoplasma infection, in which the two intersect.

Copyright © 1996-2013, Eric H. Chudler, University of Washington