Hiding information

For most of my adulthood, I used two personal Google accounts. One was my social account, which I used to communicate with friends and family, track my search history, track my calendar, and interact with commerce. I didn’t worry about much about data privacy on this account, as it was very much my “public” personal account, out and visible in the world. Consequently, my digital ads reflected my “public” personal life, as seen through my searching and browsing: parenting goods, gadgets, and generic man stuff, like trucks and deodorant.

My other personal account, however, was very much private. It was the account I used to search for information about gender. I used it to log in to forums were I lurked to learn about other transgender people’s experiences. I used it to ask questions I wouldn’t ask anyone one else, and didn’t want anyone else to know I was asking. I always browsed in Chrome’s incognito mode, to make sure there was no search history on my laptop. I kept my computer password locked at all times. Every time I finished a search, I closed my browser tabs, cleared my browser history, and erased my Google and YouTube histories, and cleared the autocomplete cache. Google still had my search logs of course, but I took the risk that someone might gain access to my account, or worse, that some friend or colleague who worked at Google might access my account and associate it with me. And these weren’t easy risks to take: being outed as transgender, for most of my adulthood, felt like it would be the end of my marriage, my family, my career, and my life. Privacy was the only tool I had to safely explore my identity, and yet, as much control as I was exerting over my privacy, the real control lie with Google, as I had no way of opting out of its pervasive tracking of my life online.

These two lives, one semi-private, and one aggressively private, are one example of why privacyprivacy: Control over information about one’s body and self. and securitysecurity: Efforts to ensure agreements about privacy. matter: they are how we protect ourselves from the release of information that might harm us and how we ensure that this protection can be trusted. In the rest of this chapter, we will define these two ideas and discuss the many ways in which they shape information systems and technology.

Privacy

One powerful conception of privacyprivacy: Control over information about one’s body and self. is as a form of control over others’ access to bodies, objects, places, and information 8 8 Adam D. Moore (2008). Defining privacy. Journal of Social Philosophy.

Of course, precisely what degree or kinds of control one has over their privacy, is often determined by culture 6 6 Helena Leino-Kilpi, Maritta Välimäki, Theo Dassen, Maria Gasull, Chryssoula Lemonidou, Anne Scott, and Marianne Arndt (2001). Privacy: a review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies.

The culturally-determined nature of privacy is even more visible in public spaces. For example, when you’re walking through a public park, you might expect to be seen. But do you expect to be recognized? Do you expect the contents of your smartphone screen to be private? How much personal space do you expect between you and others in public spaces? Some scholars argue that the distinction between public and private is both a false dichotomy, but also more fundamentally culturally and individually determined than we often recognize 10 10 Helen Nissenbaum (1998). Protecting Privacy in an Information Age: The Problem of Privacy in Public. Law and Philosphy.

While privacy in physical contexts is endlessly complex, privacy in digital spaces is even more complicated. What counts as private and who has control? Consider Facebook, for example, which aggressively gathers data on its users and surveils their activities online. Is Facebook a “public” place? What expectations does anyone have of privacy while using Facebook, or while browsing the web? And who is in control of one’s information, if it is indeed private? Facebook might argue that every user has consented to the terms of service, which in its latest versions, disclose the data gathered about your activities online. But one might counter that claim, arguing that consent at the time of account creation is insufficient for the ever evolving landscape of digital surveillance. For example, Facebook used to just track how I interacted with Facebook. Now it tracks where I am, how long I’m there, what products I browse on Amazon, whether I buy them, and then often sells that information to advertisers. I never consented to those forms of surveillance.

Much of the complexity of digital privacy can be seen by simply analyzing the scope of surveillance online. Returning to Facebook, for example, let us consider its Data Policy . At the time of this writing, here is the data that Facebook claims to collect:

- Everything we post on Facebook, including text, photos, and video

- Everything we view on Facebook and how long we view it

- People with whom we communicate in our contact books and email clients

- What device we’re using and how it’s connected to the internet

- Our mouse and touchscreen inputs

- Our location

- Our faces

- Any information stored by other websites in cookies, which could be anything

It then shares that information with others on Facebook, with advertisers, with researchers, with vendors, and with law enforcement. This shows that, unlike in most physical contexts, your digital privacy is largely under the control of web sites like Facebook, and the thousands of others you likely visit. Under the definition of privacy presented above, that is not privacy at all, since you have little control or autonomy in what is gathered or how it is used.

Many people have little desire for this control online, at least relative to what they gain, and relative to the trust they place in particular companies to keep their data private 5 5 Nina Gerber, Paul Gerber, Melanie Volkamer (2018). Explaining the privacy paradox: A systematic review of literature investigating privacy attitude and behavior. Computers & Security.

But for some, the risks are quite concrete. For example, some people suffer identity theft , in which someone maliciously steal one’s online identity to access bank accounts, take money, or commit crimes using one’s identity. In fact, this happens to an estimated 4% of people in the United States each year, suggesting that most people in their lifetimes will suffer identity theft 1 1 Keith B. Anderson, Erik Durbin, and Michael A. Salinger (2008). Identity Theft. Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Stine Eckert, Jade Metzger-Riftkin (2020). Doxxing. The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication.

Gorden A. Babst (2018). Privacy and Outing. Core Concepts and Contemporary Issues in Privacy.

Charleton D. McIlwain (2019). Black Software: The Internet and Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter. Oxford University Press.

As we’ve noted, one critical difference between physical and online privacy is who is in control: online, it is typically private organizations, and not individuals, who decide what information is gathered, how it is used, and how it is shared. This is ultimately due to centralizationcentralization: Concentrating control over information or information systems to a small group of people. . In our homes, we have substantial control over what forms of privacy we can achieve. But we have little control over Facebook’s policies and platform, and even more importantly, there is only one Facebook, whose policies apply to everyone uniformly—all 2.7 billion of them. Therefore, even if a majority of users aren’t concerned with Facebook’s practices, the minority who are must live with whatever majority-serving design choices that Facebook makes.

At the heart of many issues around privacy, especially in digital contexts, is the notion of contextual integrityconextual integrity: The degree to which the context of information is preserved in its presentation, distribution, and interpretation. . Recall from Chapter 3 that the context of information is not just a separate description of the situations in which data was captured, but also details that intricately determine the meaning of data. For example, imagine someone posts a single sad face emoji in a tweet after election day in the United States. What that data means depends on the fact that the tweet occurred on that day and on the particular politics of the author. In fact, it might not have to do with the election at all. Context, therefore, is central in determining meaning. Contextual integrity, therefore, is about preserving the context in which data is gathered, and ensuring that the use of data is bound to the norms of that context 9 9 Helen Nissenbaum (2004). Privacy as contextual integrity. Washington Law Review.

Jessica Vitak (2012). The impact of context collapse and privacy on social network site disclosures. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media.

One of the most notable examples of context collapse was the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which a British consulting firm used Facebook services to gather the likes and posts data of 50 million Facebook users, then used it to predict the users’ Big 5 personality type to target political ads during the 2016 U.S. election. This type of data had been used similarly before, most notably by the Obama campaign, but in that case, user consent was given. Cambridge Analytica never sought such consent. Surely, none of these 50 million Facebook users expected their data to be used to sway the outcome of the 2016 election, especially to shape what political advertisements they saw on the platform.

Cambridge Analytica is one example of a much broader economic phenomenon of surveillance capitalism 12 12 Shoshana Zuboff (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Public Affairs.

Therefore, while privacy may seem simple, it is clearly not, especially in digital media. And yet the way that modern information technologies make it possible to capture data about our identities and activities at scale, without consent, and without recourse for when there is harm, demonstrates that privacy is only becoming more complex.

Security

In one sense, the only reason security matters is because privacy matters: we need security to restrict access to private information, to prevent the many harms that occur when private information is improperly disclosed. This is equally true for individuals who are trying to keep part of their identity or activities private, as well as for large corporations, in that they may have secrets about innovations or sales to keep private, while also having data about their customers that they might want to keep private. Access controlaccesscontrol: A system for making and enforcing promises about privacy. is a security concept essential to keeping promises about privacy.

There are two central concepts in access control. The first is authorizationauthorization: Granting permission to access private data. , which is about granting permission to gain access to some information. We grant authorization in many ways. We might physically provide some private information to someone we trust, such as form with our social security number, to a health care provider at a doctor’s office. Or, in a digital context, we might give permissions for specific individuals to view a document we’re storing in the cloud. Authorization is the fundamental mechanism of ensuring privacy, as it is how individuals and organizations control who gets information.

The second half of access control is authentication , which are ways of proving that some individual has authorization to access some information. In the example of the doctor’s office above, authentication might be subjective and fluid, grounded in a trust assessment about the legitimacy of the doctor and their staff and their commitments to use the private information only for certain purposes, such as filing health insurance reimbursements. Online, authentication may be much more objective and discrete, involving passwords or other secrets used to prove that a user is indeed the person associated with a particular user account.

While physical spaces are usually secured with physical means (e.g., proving your identity by showing a government issued ID), and digital spaces are usually secured through digital means (e.g., accessing data by providing data about your identity), digital security also requires physical security. For example, a password might be sufficient for accessing a document in the cloud. But one might also be able to break into a Google data center, find the hard drive that stores the document, and copy it. Therefore, security is necessarily a multilayered endeavor.

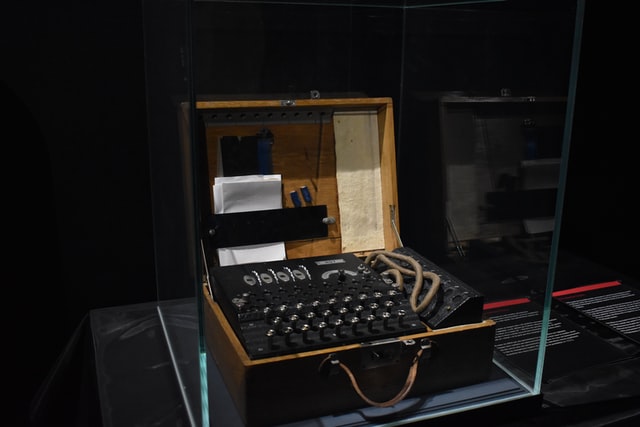

The first layer of security is data . Securing data typically involves encryptionencryption: Encoding data with a secret so that it can only be read by those who possess the secret. , which is the process of translating data from a known encoding to some unknown encoding. Encryption requires key (also known as a secret), and an algorithm (also known as a cipher) that transforms the data in a way that can only be undone with the key. Critically, it is always possible to decrypt data without the key by guessing the key, but if the key is large enough, it may take substantial computing power—and many years, decades, or longer—making some levels of encryption effectively impossible to crack. Some encryption is symmetric in that it uses the same key to encrypt and decrypt the data, meaning that all parties who want to read the data need the same key. This has the downside of requiring all parties to be trusted to safely store the key, keeping it private. One remedy to this is asymmetric encryption, where a public key was used to encrypt messages, but a separate private key was used to decrypt them. This is like a post office box: where it’s easy to put things in, but only person with the private key can take stuff out. Given these approaches, breaching data security simply means accessing and decrypting data, usually through “brute force” guessing of the key.

Encrypting data is not enough to secure data. The next layer of security required is in the operating systems of computers. This is the software that interfaces between hardware and applications, reading things from storage and displaying them to screen. Securing them requires operating systems that place strict controls over what data can and cannot be read from storage. For example, Apple and Google are well known for their iOS and Android sandboxing approaches, which disallow one application to read data from another without a user’s permission. This is what leads to so many request for permission dialogs. Breaching operating system security, therefore requires finding some way of overcoming these authorization restrictions by finding a vulnerability that the operating system developers have overlooked.

The applications running in an operating system also need to be secured. For example, it doesn’t matter if data is encrypted and an operating system sandboxes apps if the app is able to decrypt your data, read it, and then send it to a malicious entity, decrypted. Securing software, much like securing operating system, requires ensuring that private data is only ever accessed by those with authorization. This is where iOS and Android often differ: because there is only one iOS app store, and Apple controls it, Apple is able to review the implementation of all apps, verifying that they comply with Apple’s privacy policy and testing for security vulnerabilities. In contrast, there are many ways to obtain Android apps, only some of which provide these privacy and security guarantees. Breaching software simply requires finding a vulnerability that developers overlooked, and using it to access private data.

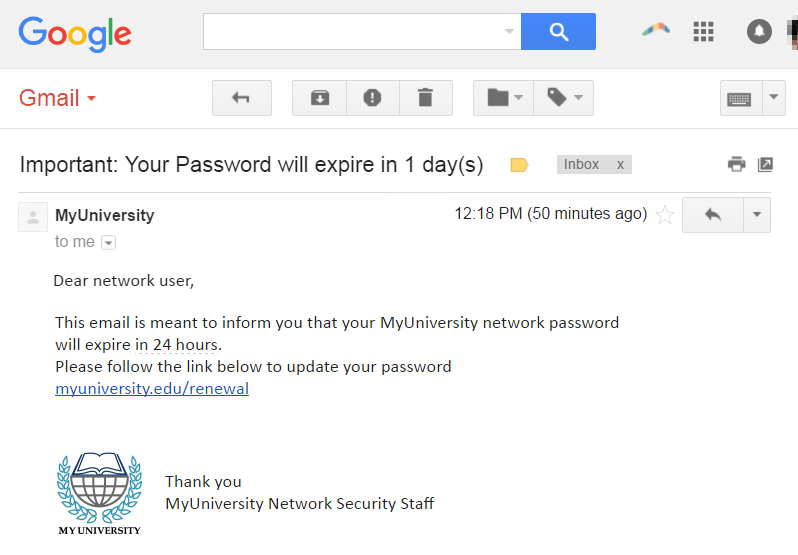

Securing data and software alone is not sufficient; people must follow security best practices. This means not sharing passwords and keeping encryption keys private. If users disclose these things, no amount of security in data or code will protect the data. One of the most common ways to breach people’s security practices is to trick them into disclosing authorization secrets. Known as phishing , this typically involves sending an email or message to a user that appears trustworthy and official, asking someone to log in to the website to view a message. However, the links in these phishing emails instead go to a malicious site and record the password you enter, giving the identity thief access to your account. Practices like two-factor authentication—using a password and a confirmation on your mobile device—can reduce the feasibility of phishing. Other approaches to “breaching” people can be more aggressive, including blackmail, to compel someone to disclose secrets by threat.

Even if all of the other layers are secure, organizational policy can have vulnerabilities too. For example, if certain staff have access to encryption keys, and become disgruntled, they may disclose the keys. Or, staff who hold secrets might inadvertently disclose them, accidentally copying them to a networked home backup of their computer, which may not be as secure as the networks at work.

All of these layers of security, and the many ways that they can be breached, may make security feel hopeless. Moreover, security can impose tradeoffs on convenience, forcing us to remember passwords, locking us out of accounts when we forget them. And all of these challenges and disruptions, at best, mean that data isn’t breached, and privacy is preserved. This can seem especially inconvenient if one isn’t concerned about preserving privacy, especially when breaches are infrequent and seem inconsequential.

Of course, it may be that the true magnitude of potential consequence of data breaches is only beginning to come clear. In 2020, for example, the U.S. Government, in cooperation with private industry, discovered that the Russian government had exploited the software update mechanism of a widely used IT Management solution called SolarWinds . Using this exploit, the Russian government gained access to the private data and activities of tens of thousands of government and private organizations worldwide, including the U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Department of Energy, and the U.S. Treasury. In fact, the breach was so covert, it’s not yet clear what the consequences were: the Russian government may have identified the identity of U.S. spies, it may have interfered with elections, it may have gained access to the operations of the U.S. electrical grid, and more. There are good reasons why this data was private; Russia might, at any point, exploit that data for power, or worse, to cause physical harm.

Other emerging trends such as ransomware 4 4 Alexandre Gazet (2010). Comparative analysis of various ransomware virii. Journal in Computer Virology.

Privacy may not matter to everyone, but it does matter to some. And in our increasingly centralized digital age, what control you demand over your privacy shapes what control other people have. Therefore, secure your data by following these best practices:

- Use a unique password for every account

- Use two-factor authentication wherever possible

- Use a password manager to store and encrypt your passwords

- Assume every email requesting a login is a phishing attack, verifying URL credibility before clicking them

- Always install software updates promptly to ensure vulnerabilities are patched

- Ensure that websites you visit use the HTTPS protocol, encrypting data you send and receive

- Read the privacy policies of applications you use, and if you can imagine a way that the the data gathered might harm you or someone else. Demand that it not be gathered or refuse to use the product.

Is all of this is inconvenient? Yes. But ensuring your digital privacy not only protects you, but also others, especially those vulnerable to exploitation, harassment, violence, and other forms of harm.

Podcasts

Want to learn more about privacy and security? Consider these podcasts, which engage some of the many new challenges that digital privacy and security pose on society:

- Right to be Forgotten, Radiolab . This podcast discusses the many challenges of archiving private data, and how the context of that data can shift over time, causing new harm.

- What Happens in Vegas... is Captured on Camera, In Machines We Trust . Discusses the increasing use of facial recognition in police surveillance and the lack of transparency, oversight, and policy that has led to its abuse.

- What Cops Are Doing With Your DNA, What Next: TBD, Slate . Discusses the increasing use of open-source DNA platforms to solve crimes, and the problematic ways in which people who never share their DNA still might be implicated in crimes.

- Who is Hacking the U.S. Economy?, The Daily . Discusses cyberattacks, ransomware, and the adversarial thinking required to prevent and respond to them.

- Why Apple is About to Search Your Files, The Daily . Discusses the complex tensions between privacy, safety, and law in Apple’s child sexual abuse survellance.

References

-

Keith B. Anderson, Erik Durbin, and Michael A. Salinger (2008). Identity Theft. Journal of Economic Perspectives.

-

Gorden A. Babst (2018). Privacy and Outing. Core Concepts and Contemporary Issues in Privacy.

-

Stine Eckert, Jade Metzger-Riftkin (2020). Doxxing. The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication.

-

Alexandre Gazet (2010). Comparative analysis of various ransomware virii. Journal in Computer Virology.

-

Nina Gerber, Paul Gerber, Melanie Volkamer (2018). Explaining the privacy paradox: A systematic review of literature investigating privacy attitude and behavior. Computers & Security.

-

Helena Leino-Kilpi, Maritta Välimäki, Theo Dassen, Maria Gasull, Chryssoula Lemonidou, Anne Scott, and Marianne Arndt (2001). Privacy: a review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies.

-

Charleton D. McIlwain (2019). Black Software: The Internet and Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter. Oxford University Press.

-

Adam D. Moore (2008). Defining privacy. Journal of Social Philosophy.

-

Helen Nissenbaum (2004). Privacy as contextual integrity. Washington Law Review.

-

Helen Nissenbaum (1998). Protecting Privacy in an Information Age: The Problem of Privacy in Public. Law and Philosphy.

-

Jessica Vitak (2012). The impact of context collapse and privacy on social network site disclosures. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media.

-

Shoshana Zuboff (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Public Affairs.