Managing information

By high school, most of my hobbies were on a computer. I liked creating art in Microsoft Paint; I liked editing sounds. And my emerging hobby of making simple games in the BASIC programming language, aided by my stack of 3-2-1 Contact magazines and their print tutorials, meant that I always had a few source files I was working on. All of my data fit onto a single 1.44 MB 3.5“ floppy disk, which I carried around in my backpack and inserted into the home and school computers whenever I had some time to play. Inspired by my mother’s love of paper planners, I kept it neatly organized, with folders for each project, and text file with a list of to do’s. With no email and no internet, the entirety of my data archive was less than a megabyte. Managing my projects meant making sure I didn’t drop my floppy disk in a puddle or crush it in my backpack.

Much later, when I was Chief Technology Officer (CTO) of a startup I had co-founded, my information management problems were much more complex. I had a team of six developers and one designer to supervise; the rest of the company had a half dozen sales, marketing, and business development people, in addition to our CEO. We had hundreds of critical internal documents to support engineering, marketing, and sales, and with a growing team, we had a desperate need for for onboarding materials. We had a web scale service automatically answering the questions of hundreds of thousands of customer questions on our customer’s websites, and our customers had endless questions about the patterns in that data. Our sales team needed to manage data about customer interactions, our marketing team needed to manage data about ad campaigns, and our engineering team needed to manage data about the availability and reliability of our 24/7 web services, especially after the half dozen releases each day. And atop all of this, our CEO needed to create elaborate quarterly board meeting presentations that drew upon all of this data, summarizing our sales, marketing, and engineering progress. Our critical data spanned Salesforce, Marketo, GitHub, New Relic, and a dozen Google services. Our success as a business depended on our ability to organize, manage, and learn from that data to make strategic decisions. (And I won’t pretend we succeeded).

Both of these stories are information managementinformation management: The systematic and strategic collection, storage, retrieval, and analysis of information for some purpose. stories, one personal, and one organizational. And they both stem from the observation we’ve made throughout this book that information has value. The critical difference between the two, however, was a matter of scale. When information in scarce, there’s little need for organization or management. But when it is abundant—especially when it is too abundant to fully comprehend—we need to manage it to get value out of it. In the rest of this chapter, we’ll discuss some of these problems of information management, both personal, and organizational, and connect these ideas to the many challenges we’ve raised in prior chapters.

The economics of attention

What determines when information management becomes necessary? The answer to this question goes back to some formative work from Herb Simon, who said in his book Designing Organizations for an Information-rich World 8 8 Herbert A. Simon (1971). Designing Organizations for an Information-rich World. Johns Hopkins University Press.

In an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.

Herbert A. Simon (1971). Designing Organizations for an Information-rich World. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Simon went on to frame the problem of attention allocation as an economic and management one, noting that many at the time had incorrectly framed organizational problems as one of a scarcity of information, rather than one of a scarcity of attention. Instead, he argued that in contexts of information abundance, the key problem is figuring what information exists, who needs to know it and when, and archiving it in ways that it can be accessed by those people when necessary.

These ideas of identifying and managing information, described in Simon’s book Administrative Behavior 6 6 Herbert A. Simon (1966). Administrative Behavior. Free Press.

Personal information management

While most of Simon’s ideas were applied to organizations such for-profit businesses and government institutions, they also shaped a body of work on personal information management problems 9 9 Jaime Teevan, William P. Jones (2011). Personal Information Management. University of Washington Press.

There are many kinds of information that can be considered “personal”:

- Information that people keep, whether stored on paper or in digital form. This includes critical document such as licenses, birth certificates, and passports, but also personally meaningful documents like mementos, letters, and other information-carrying documents.

- Information about a person but kept by others. This includes things like health or student records and histories of tax or bill payments.

- Information directed towards a person, such as emails, social media messages, and advertisements.

For all of the information above, importance may vary. For example, most of us have some critical information (e.g., a birth certificate proving citizenship, or some memento that reminds us of a lost loved one). Other information might be useless to us (e.g., Google’s records of which ads they have shown us, or spam we received long ago that still sits in our email archive). This variation in importance, and the shifting degree to which information is important, is what creates problems of personal information management.

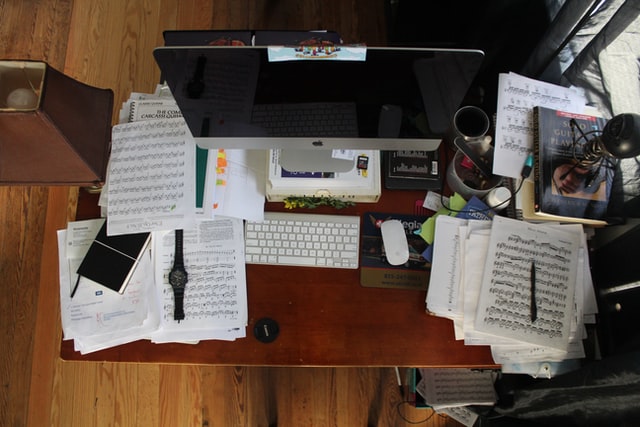

Some of these are problems of maintenance and organization . For example, some people might store their personal data in haphazard, disordered ways, with no particular scheme, no habits of decluttering 4 4 Thomas W. Malone (1983). How do people organize their desks? Implications for the design of office information systems. ACM Transactions on Information Systems.

Steve Whittaker, Tara Matthews, Julian Cerruti, Hernan Badenes, and John Tang (2011). Am I wasting my time organizing email? A study of email refinding. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Some problems are of managing privacy , security , and sharing . For example, in the United States, most citizens have Social Security cards. This is sensitive information, since it is often used to access financial resources or government services. Every individual has the problem of how to secure that private information, and whom to share it with. But not every person has practices that actually secure it 13 13 Gizem Öğütçü, Özlem Müge Testik, and Oumout Chouseinoglou (2016). Analysis of personal information security behavior and awareness. Computers & Security.

Most problems, of course, are of retrieving and using personal information. Where is that photo of my grandmother when I was a child? Where is that bill I was supposed to pay? Where is my birth certificate? These problems of personal information retrieval are exacerbated by the problems above: if personal information is not maintained, organized, archived, and secured, finding information will be more difficult, and using it may be harder as there may be no metadata to help remind someone of the context in which it was gathered. This can create entirely new problems of re-finding information 10 10 Sarah K. Tyler, Jaime Teevan (2010). Large scale query log analysis of re-finding. ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining.

All of these challenges are the same ones that archivists in libraries and museums face 1 1 Peter Buneman, Sanjeev Khanna, Keishi Tajima, and Wang-Chiew Tan (2004). Archiving scientific data. ACM Transactions on Database Systems.

Organizational information management

While problems of information management are universal at some level, they can feel quite different at different scales. Managing personal information might feel like a chore, but managing organizational information might be the difference between an organization’s success or failure. For a for-profit business, the right information can be the difference between a profit and loss; for a not-for profit organization, such as the American Cancer Society , it might be the difference between life and death for cancer patients worldwide, slowing research and advocacy.

It is important to distinguish here between “organization” as it is used on the context of management, and “organization” as we are using it here. The first usage concerns the ways in which we create order around data and metadata to facilitate searching and browsing. The second usage concerns groups of people, and the patterns and processes of communication in which they engage to achieve shared goals. Confusingly, then, organizations create value from information by organizing it.

What value might organizations get from organizing information? In Administrative Behavior 6 6 Herbert A. Simon (1966). Administrative Behavior. Free Press.

Herbert A. Simon (1963). The Sciences of the Artificial. MIT Press.

After Simon’s book, and the role of computers in expanding the amount of information available to organizations, the field of information management began to emerge to try to solve the problems that Simon framed. Several further challenges emerged 2 2 Chun Wei Choo (2002). Information Management for the Intelligent Organization. Information Today.

- Where does data come from? This includes all of the challenges of creating explicit systems to capture data and metadata. Consider Amazon, for example, which aggressively tracks browsing and use of its retail services; it has elaborate teams responsible for instrumenting web pages and mobile apps to monitor every click, tap, and scroll on every product. Managing that data collection is its own complex enterprise, intersecting with methods in software engineering, data science, and human-computer interaction.

- Where is data stored? This includes all of the problems of data warehousing 5 5

Paulraj Ponniah (2011). Data warehousing fundamentals for IT professionals. John Wiley & Sons.

, including data schemas to capture metadata, databases to implement those schema, backups, real-time data delivery, and likely data centers that can scale to archive that data. At Amazon, this means creating web-scale, high performance data storage to track the activity of hundreds of millions of shoppers in real-time. - Who is responsible for data? Someone in an organization needs to be in charge of ensuring data quality, reliability, availability, and legal compliance. Because data is valuable, they also need to be responsible for data continuity, in the case of disasters like earthquakes, fires, floods, power outages, or network outages. At Amazon, there are not only people at Amazon Web Services who take on some of these responsibilities, but also people in the Amazon retail division who ensure that the data being stored at AWS is the data Amazon retail needs.

Managing information in an organization means answering these questions.

As information management emerged, so did the role of Chief Information Officer 3 3 Varun Grover, Seung-Ryul Jeong, William J. Kettinger, and Choong C. Lee (1993). The chief information officer: A study of managerial roles. Journal of Management Information Systems.

Hugh J. Watson, Barbara H. Wixom (2007). The current state of business intelligence. IEEE Computer.

As digital information technology makes it easier than ever to gather data, our personal and professional lives will pose ever greater challenges of managing information, and our attention on it. Of course, underlying all of these issues of management are also the same moral and ethical questions we have discussed in prior chapters. What responsibility do individuals and organizations have as they gather and analyze data? What responsibilities do individuals and organizations have to prevent harm from data? How do we ensure that how we encode and archive data is respectful of the rich diversity of human identity and experience? In what moral circumstances should we delete data or change archives? These many challenges are at the heart of our decisions about what to do with the data we gather, and decisions about whether to gather it at all.

References

-

Peter Buneman, Sanjeev Khanna, Keishi Tajima, and Wang-Chiew Tan (2004). Archiving scientific data. ACM Transactions on Database Systems.

-

Chun Wei Choo (2002). Information Management for the Intelligent Organization. Information Today.

-

Varun Grover, Seung-Ryul Jeong, William J. Kettinger, and Choong C. Lee (1993). The chief information officer: A study of managerial roles. Journal of Management Information Systems.

-

Thomas W. Malone (1983). How do people organize their desks? Implications for the design of office information systems. ACM Transactions on Information Systems.

-

Paulraj Ponniah (2011). Data warehousing fundamentals for IT professionals. John Wiley & Sons.

-

Herbert A. Simon (1966). Administrative Behavior. Free Press.

-

Herbert A. Simon (1963). The Sciences of the Artificial. MIT Press.

-

Herbert A. Simon (1971). Designing Organizations for an Information-rich World. Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

Jaime Teevan, William P. Jones (2011). Personal Information Management. University of Washington Press.

-

Sarah K. Tyler, Jaime Teevan (2010). Large scale query log analysis of re-finding. ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining.

-

Hugh J. Watson, Barbara H. Wixom (2007). The current state of business intelligence. IEEE Computer.

-

Steve Whittaker, Tara Matthews, Julian Cerruti, Hernan Badenes, and John Tang (2011). Am I wasting my time organizing email? A study of email refinding. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

-

Gizem Öğütçü, Özlem Müge Testik, and Oumout Chouseinoglou (2016). Analysis of personal information security behavior and awareness. Computers & Security.