The peril of information

When I was in high school, I was a relatively good student. All but one of my grades were A’s, I was deeply curious about mathematics and computer science, and I couldn’t wait to go to college to learn more. My divorced parents weren’t particularly wealthy, and so I worked many part-time jobs to save up for college applications and AP exam fees, bagging groceries, babysitting, and tutoring. It didn’t leave much time for extracurriculars. I was sure that colleges would understand my circumstances and see my promise. But when the decisions came back, I’d only been admitted to two places: my public state university, and the University of Washington, but the latter only offered a $500 loan, and I had no college savings. My dreams were shattered because the committee ignored the context of the information I gave them: that I had no time to stand out in any other way beyond grades because I was busy working, supporting my family.

Familiar stories like this show that not all information is good information or used in good ways. In fact, as powerful as information is, there is nothing about power that is inherently good either. In fact, power can be perilous. The admissions committees at my dream universities had great power to shape my fate through their decisions, and the information they asked me to share didn’t allow me to tell my whole story. And my lack of guidance from school counselors, teachers, and parents meant that I didn’t know what information to give to increase my chances. The committee’s decisions, while quite a powerful form of information, were therefore in no way neutral. In fact, behind their decisions were a particular set of values and notions of merit that shaped the information they requested, the information they provided, and the decision they sent me in thin envelopes in the mail.

With power comes peril

What is power? Within the context of society, powerpower: The capacity to influence and control others. is capacity to influence the emotions, behavior, and opportunities of other people. Power and information are intimately related in that information is itself a form of influence. When you listen to someone speak or read someone’s writing, the information they convey can shape our thoughts and ideas. When you take up physical space and give non-verbal cues of a reluctance to move, you are signaling information about what physical threats you might impose. When you share some information on social media, you are helping an idea find its way into other people’s minds. All of these forms of communication are therefore forms of power.

But power is not just communication. Power also resides in our knowledge and beliefs, shaped by information we received long ago. As children, for example, many of us learn ideas of racism, sexism, ableism, transphobia, xenophobia, and other forms of discrimination, fear, or social hierarchy. These ideas, beliefs, and assumptions form systems of power, in which those high in social hierarchies can influence who has rights, resources, and opportunity. Sociologist Patricia Collins called these forms of power, and their many interactions, the matrix of dominationmatrix of domination: The system of culture, norms, and laws designed to maintain particular social hierarchies of power. 1 1 Patricia Collins (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routeledge.

D’Ignazio and Klein, in their book Data Feminism 2 2 Catherine D'Ignazio, Lauren F. Klein (2020). Data Feminism. MIT Press.

Consequences of information

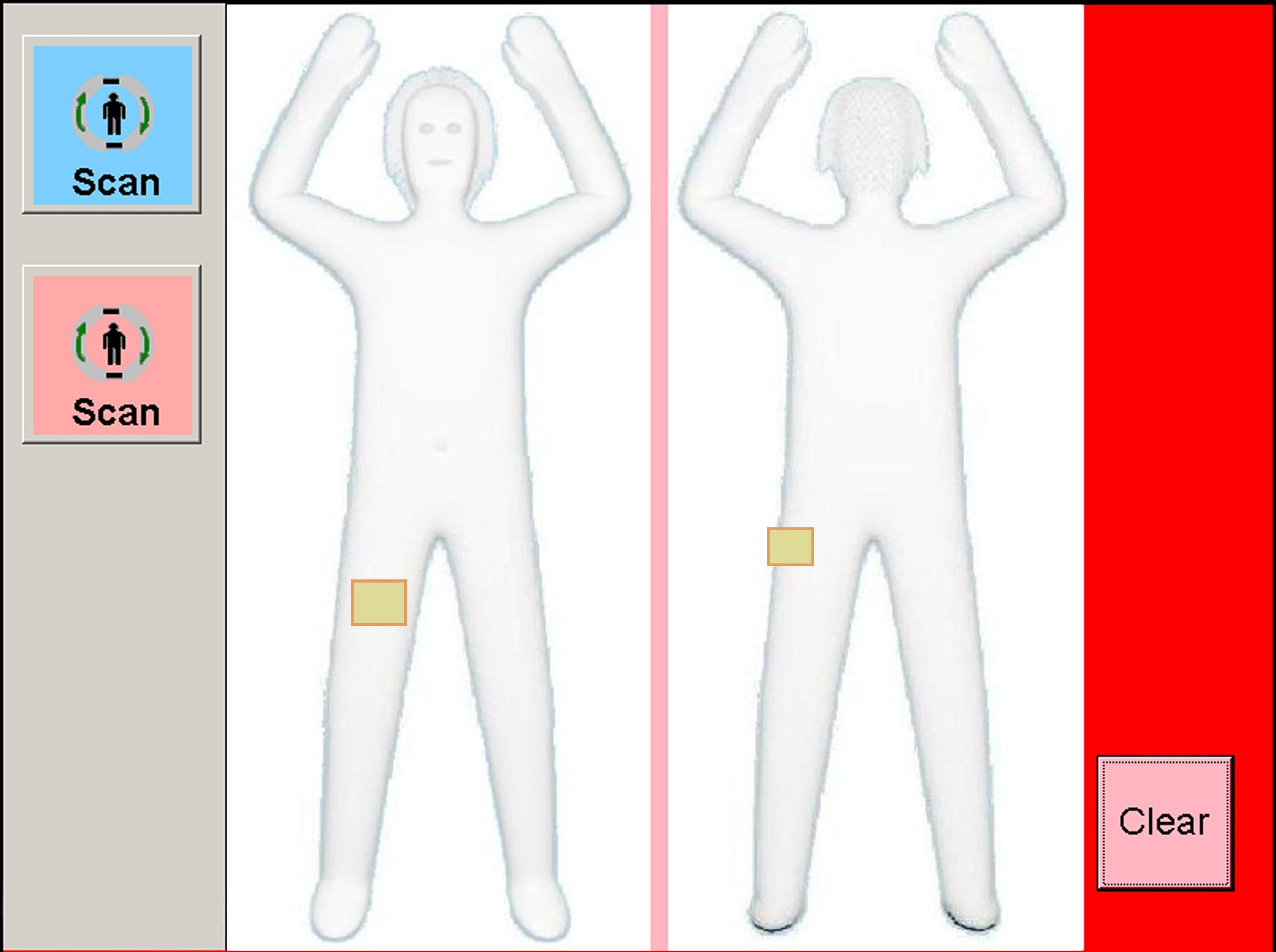

Let’s consider some of the many ways that information and its underlying values can be perilous. One seemingly innocuous problem with information is that it can misrepresent . For example, when I go to an airport in the United States, I often have to be scanned by a TSA body scanner. This scanner creates a three dimensional model of the surface of my body using x-ray backscatter. The TSA agent then selects male or female, and the algorithm inside the scanner compares the model of my body to a machine learned model of “normal” male and female bodies, based on a data set of undisclosed origin. If it finds discrepancies between the model of my body and its model of “normal,” I am flagged as anomalous, and then subjected to a public body search by an agent. For most people, the only time this will happen is if there is something that looks like a gun to the scanner. But many transgender people such as myself, as well as other people whose bodies do not conform to stereotypically gendered shapes such as those with disabilities, are frequently flagged and searched. This discrimination, in which “normal” bodies are protected by security, and “anomalous” bodies are invasively searched and sometimes humiliated, derives from how the TSA scanners and the TSA agents misrepresent the actual diversity of human bodies. They misrepresent this diversity because of the matrix of domination that excludes gender non-conforming and disabled people from consideration in design.

Information can also be false or misleading, misinforming its recipient. This was perhaps no more apparent during President Trump’s 2016-2020 term, in which he wrote countless tweets that were demonstrably false about many subjects, including COVID-19. For example, on October 5th, 2020, just after being released from the hospital a few days after testing positive for the virus, he tweeted:

I will be leaving the great Walter Reed Medical Center today at 6:30 P.M. Feeling really good! Don’t be afraid of Covid. Don’t let it dominate your life. We have developed, under the Trump Administration, some really great drugs & knowledge. I feel better than I did 20 years ago!

Whether or not the President was intentionally giving bad advice, or this was simply fueled by his steroid injection, its impact was clear, as the tweet was shortly followed by the Autumn 2020 wave of infections in the United States, fueled by conspiracy theories framing the virus as a hoax, and pressure on state and local officials to avoid stricter public health rules. Hundreds of thousands of people died in the U.S., likely due partly to the President’s persistent spreading of misleading information about the virus and many years of similar misinformation about vaccines, spread by parents who did not understand or believe the science of immunology.

Information can also disinform . Unlike misinformation, which is independent of intent, disinformation is information that people know to be false, and spread in order to influence behavior in particular ways. For example, many states in the United States require doctors who are administering abortions to lie to patients about the effects of abortion; the intent of these laws is framed as informed consent, but many legislators have admitted that their actual purpose is to disincentivize people from following through on abortions. Similarly, QAnon conspiracies , have created even larger collective delusions that lead to entirely alternate false realities. Disinformation, then, is a form of power and influence through deception.

Some information may be true, but may be created to manipulate , by misrepresenting its purpose. For example, in the video above, technologist Jaron Lanier discusses how social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram (also owned by Facebook) are fundamentally about selling ads. Facebook is not presented this way—in fact, it is rather innocuously presented as a way to stay connected with friends and family—but its true purpose is to ensure that when an advertisement is shown in a social media feed that we attend to it and possibly click on it, which makes Facebook money. Similarly, a “like” button is presented as a social signal of support or affirmation, but its primary purpose is to help generate a detailed model of our individual interests, so that ads may be better targeted towards us. Independent of whether you think this is a fair trade, it is fundamentally manipulation, as Facebook misrepresents the motives of its features and services.

Information can also overload 4 4 Benjamin Scheibehenne, Rainer Greifender, Peter M. Todd (2010). Can There Ever Be Too Many Options? A Meta‐Analytic Review of Choice Overload. Journal of Consumer Research.

Sometimes, information can be addictive 3 3 Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2016). Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior.

Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2016). Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior.

Some recent research has even shown that ease of accessing information can lead to isolation 5 5 Sherry Turkle (2011). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from ourselves. MIT Press.

Information can also kill . Consider, for example, the case of the Uber autonomous driving sensor system . In March of 2018, it was driving down a highway with a human driver monitoring it. Elaine Herzberg, a pedestrian, was crossing the road with her bike at 10 p.m. The driver was not impaired, but also was not monitoring the system. The system noticed an obstacle, but could not classify it; then, it classified it as a vehicle; then as a bicycle. And finally, 1.3 seconds before impact, the system determined that an emergency braking maneuver was required to avoid a collision. However, this mode was disabled during automated driving mode, and the driver was not notified, so the car struck and killed Elaine. This critical bit of information—danger!—was never sent to the driver, and since the driver was not paying attention, someone died. Beyond automation, errors in information can kill in any safety-critical context, including flight, health care, and social safety nets that provide food, shelter, and security.

These, of course, are not the only potential problems with information. The world has an ongoing struggle with the tensions of free speech, censorship, and the many ways we have discussed above that information can do harm. With the ability of the internet to archive much of our past, there are also many open questions about what rights we have to erase information stored on other people’s computers that might tie us to a past life, a past action, or a past name or identity. These and the numerous many other questions, reinforce that information has values, and those values are intrinsically tied to the ways that we exercise control over each other.

Podcasts

The podcasts below all reveal the peril of information in different ways.

- Family Stories, Family Lies , Code Switch. Shares one story of how the origins of a family name are far more complicated than one can ever imagine, capturing a multi-generation history of love and oppression.

- A Conspiracy Theory Proved Wrong, The Daily, The New York Times . Discusses the history of the QAnon conspiracy and its aftermath after its predictions did not come true.

- No Silver Bullets, On the Media, WNCY Studios . Discusses how information and propaganda has led to far-right extremism, and how information is also used to deradicalize.

- Facebook’s CTO on Misinformation, In Machines We Trust . Facebook’s CTO describes Facebook’s struggling efforts to detect misinformation and prevent harm.

- Undercover and Over-Exposed, On the Media . Discusses the risks of freely sharing information with journalists.

References

-

Patricia Collins (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routeledge.

-

Catherine D'Ignazio, Lauren F. Klein (2020). Data Feminism. MIT Press.

-

Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2016). Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior.

-

Benjamin Scheibehenne, Rainer Greifender, Peter M. Todd (2010). Can There Ever Be Too Many Options? A Meta‐Analytic Review of Choice Overload. Journal of Consumer Research.

-

Sherry Turkle (2011). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from ourselves. MIT Press.