Research Archive

|

Form

and meaning Form

and meaning

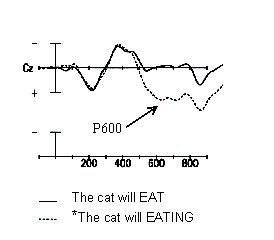

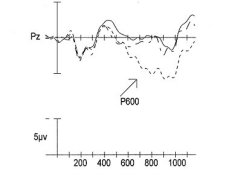

The human brain

responds differently to anomalies involving sentence form

(syntax) and sentence meaning (semantics). Semantic

anomalies elicit an N400 effect in the ERP, and our lab was

the first to show that syntactic errors elicit a large

positive wave (the P600 effect).

Our past work has

shown that this result generalizes across anomaly type,

subjects' task, and languages. Here,

we show that this result also generalizes to situations in

which the anomalies are embedded in naturalistic prose. |

|

|

Morphological

decomposition

Non-words generally elicit a larger N400

component than do real words. We report

here that non-words made up of

real morphemes elicit a brain response very similar to that

elicited by real words. This result shows that word-like

stimuli are decomposed into their constituent morphemes. |

Secon d-language

word learning d-language

word learning

Although

second-language (L2) learning is often claimed to be slow

and difficult, little is known about the rate of

second-language word learning. We report

here that adult learners' brain

activity discriminated between L2 words and non-words after

just 14 hours of classroom L2 instruction. This

occurred even though the learners were at chance when

consciously deciding if the stimuli were words or not.

Apparently, some aspects of second-language learning occur

with amazing speed. We have extended this research to

studies investigating second-language syntactic learning.

|

|

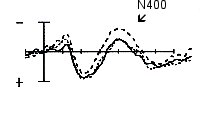

Meaning can "drive"

sentence comprehension Given that

separate syntactic and semantic processes exist, one

question is how we coordinate syntactic and semantic

knowledge when processing a sentence. The standard

theory holds that syntax alone determines how words are

initially combined to form phrases and clauses:

Syntactic structure is computed first, and sentence meaning

is derived second. Kim & Osterhout (in press) tested

this theory by presenting anomalous sentences such as "The

mysterious crime had been solving

...". The syntactic cues in the sentence require that

the noun crime be the Agent of the verb solving.

If syntax drives sentence processing, then the verb

solving would be perceived to be semantically

anomalous, as crime is a poor Agent for the verb

solve, and therefore should elicit an N400 effect.

However, although crime is a poor Agent, it is an excellent

Patient (as in solved the crime). The

Patient role can be accommodated simply by changing the

inflectional morpheme at the end of the verb ("The

mysterious crime had been solved . . .").

Therefore, if meaning drives sentence processing, then the

verb solving would be perceived to be in the wrong

syntactic form, and should therefore elicit a P600 effect.

We report that verbs like solving elicited a P600

effect, showing that a strong semantic attraction between a

predicate and an argument can determine how words are

combined, even when the semantic attraction contradicts

unambiguous syntactic cues. |

![]()