Sentence Parsing

Given that syntactic analysis seems

to be part of language comprehension, the question of exactly how

the reader or listener determines the syntactic structure of a

sentence (sentence parsing) becomes a central concern.

Researchers have examined this question by presenting sentences that

contain a syntactic ambiguity, that is, a situation in which more

than one well-formed synatctic analysis can be assigned to a string

of words. Usually, subsequent words indicate the correct

analysis. For example:

(1) The lawyer

charged that the defendant was lying.

(2) The

lawyer charged

the defendant was lying.

In (1), there is little syntactic

ambiguity. By contrast, in (2) the grammatical role of the noun

phrase the defendant is temporarily ambiguous between an

"object of the verb" role and a "subject of an upcoming clause"

role. The fact that the subject role is appropriate in this

case becomes clear only after encountering the disambiguating

auxiliary verb

was. Current theories predict that in such

situations the reader will assign the object role to the

defendant. This decision will result in a processing

problem when the auxiliary verb is encountered; under the object

analysis, the auxiliary cannot be attached to the preceding sentence

material. Consequently, this theory predicts that readers

should (at least momentarily) perceive the auxiliary verb to be

syntactically anomalous. The prediction, then, is that the

auxiliary verb in (2) should elicit a P600 effect, relative to the

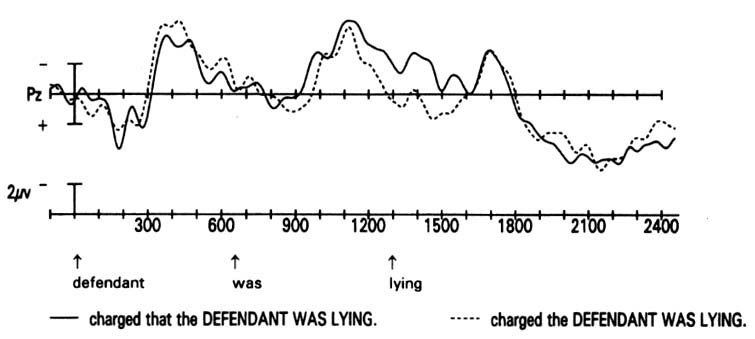

same word in (1). The figure plots ERPs to the final three

words in each sentence (defendant was lying). Arrows

indicate the onset of each word. Consistent with the

prediction, beginning at about 500 ms after onset, auxiliiary verbs

in sentences like (2) elicited a P600-like positive shift.

One interpretation of these results is that readers commit

themselves to a single syntactic analysis when confronted with

ambiguity, rather than building all possible structures in parallel

or waiting until disambiguating information indicates which analysis

is the correct one before assigning grammatical roels to words.

Just as importantly, these results show that the P600 effect is

elicited not only by outright ungrammaticalities, but also by

perceived ungrammaticalities that result solely due to how people

parse sentences.

References:

Osterhout, L. (1997). On the brain

response to syntactic anomalies: Manipulations of word position and

word class reveal individual differences.

Brain and Language, 59, 494-522.

Osterhout, L. & Holcomb, P. J.

(1992). Event-related brain potentials elicited by syntactic

anomaly. Journal of Memory and Language,

31,

785-806.

Osterhout, L., & Holcomb, P. J.

(1993). Event-related potentials and syntactic anomaly: Evidence of

anomaly detection during the perception of continuous speech.

Language and Cognitive Processes, 8, 413-438.

Osterhout, L., Holcomb, P. J., &

Swinney, D. A. (1994). Brain potentials elicited by garden-path

sentences: Evidence of the application of verb information during

parsing. Journal of Experiment Psychology: Learning, Memory, &

Cognition, 20, 786-803.

![]()