Social Stereotypes

Gender-role stereotypes exert strong effects on

behavior. For example, gender stereotypes influence mothers' perceptions of their

children's abilities and children's self-perceptions. Gender-role occupational

stereotypes play a role in job choice, hiring, promotion, and compensation. However,

research on stereotypes and their effects is beset by a problem of measurement:

Although most researchers rely on introspective self-reports, these reports do not

invariably reflect attitudes or beliefs, particularly when expression of the belief is

deemed to be socially inappropriate. It is also conceivable that a person could

maintain a belief but not be consciously aware of it.

We combined ERPs and language-sensitive ERP effects to

chart a new course for studying social stereotypes. This approach was motivated by

work in our lab showing that violations of gender agreement between a pronoun and its

antecedent (e.g., sentence (2) below) elicit a P600 effect. To examine the brain

response to violations of occupational gender stereotypes, we presented sentences like

these:

(1) The man prepared

himself for

the operation.

(2) The man prepared

herself for

the operation.

(3) The doctor prepared

himself

for the operation.

(4) The doctor prepared

herself

for the operation.

Participants made aceptability judgments after reading

each sentence. Sentences like (2) were judged to be unacceptable, but all other

sentences were usually judged to be acceptable. Thus, subjects' self-reports gave

llittle indication that sentences like (4), in which a presumed gender stereotype has been

violated, were perceived to be unacceptable or anomalous.

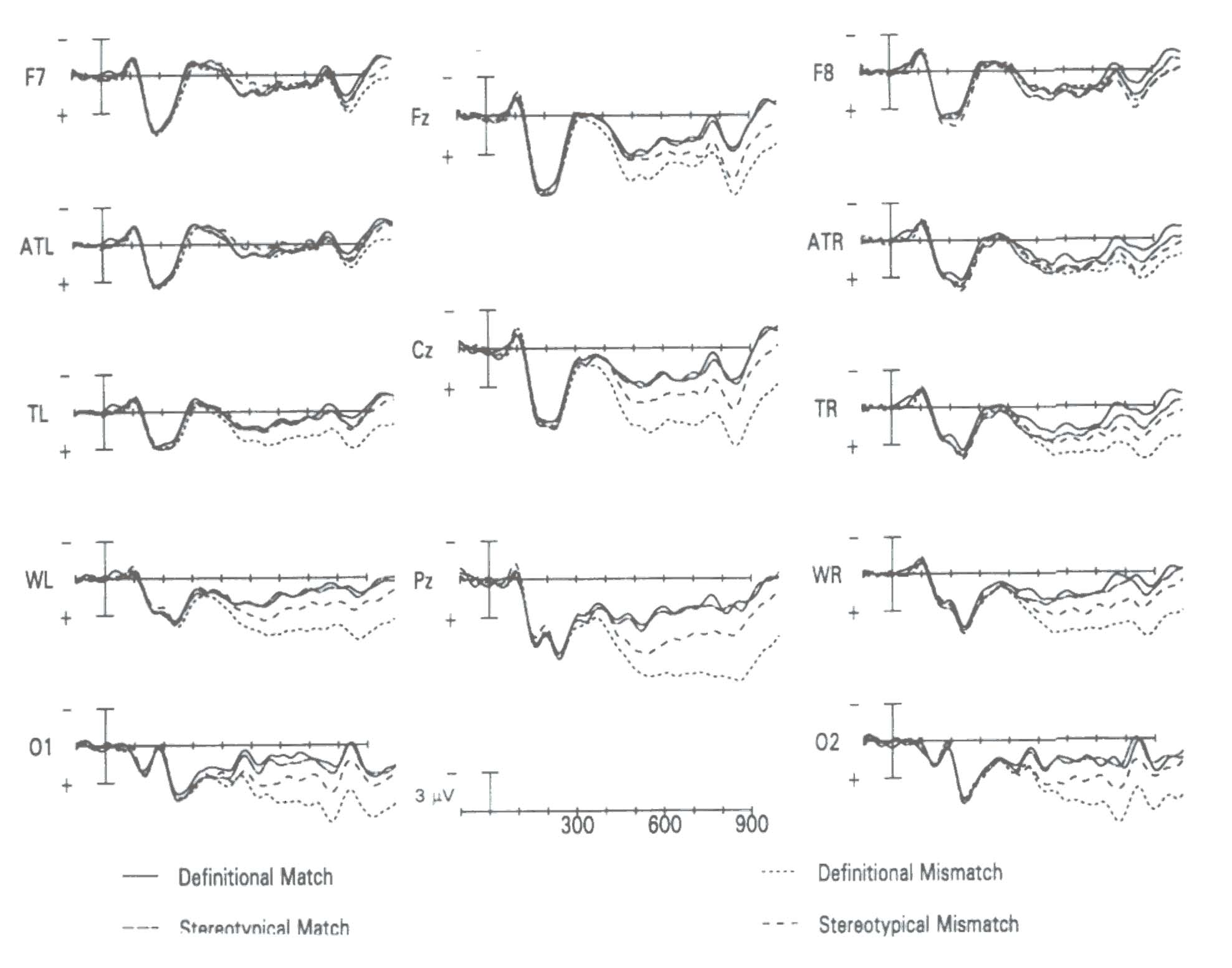

ERPs to the underlined pronoun in each sentence were of

interest and are plotted in the figure below. The vertical bar indicates onset of

the pronoun in each of the four conditions. Each hashmark represents 100 ms, and

negative voltage is plotted up. As expected, the pronoun in sentence (2), which

disagreed with the gender a definitionally male or female antecedent noun, elicited a

large P600 effect, relative to the condition in which the pronoun and antecedent noun

agreed in gender (sentence 1). The question was what would happen in sentences like

(3) and (4). Interestingly, pronouns that disagreed with the stereotypical gender of

it's antecedent noun also elicited a P600 effect, albeit one with lesser amplitude that

that elicited by the outright ungrammatical disagreement. Clearly, our subjects'

brains were classifying the stereotype violations as anomalous. This continued to

be true even when response-contingent ERPs were plotted: Even on trials on which

subjects said the stereotype-violating sentences were acceptable, the pronouns in these

sentences elicited a P600 effect.

We also observed compelling differences between our female

and male participants: Female participants exhibited a much larger-amplitude

"anomaly response" to both the definitional and stereotypical gender violations,

compared to the male participants.

References:

Osterhout, L., Bersick, M., & McLaughlin, J. (1997).

Brain potentials reflect violations of gender stereotypes. Memory and Cognition,

25,

273-285.

![]()