Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Healthcare for Indigenous Veterans | References

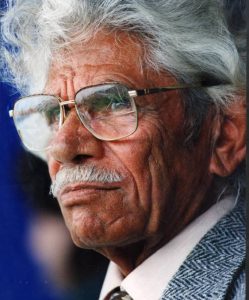

The healthcare services provided to Native Americans by the United States government have been substandard since their inception. Indigenous veterans suffer more than any other group because of the inadequacy of the programs offered by the Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (V.A.). In 2019, Senator Tom Udall and Representative Ro Khanna introduced a bill aimed at addressing this issue. The Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act focuses on creating appropriate standard care for those who have served because the problems faced by Native American civilians are compounded by the psychological and physical trauma of military service. Lack of access, understaffed facilities, and racist bureaucracy have kept indigenous veterans from receiving the care they deserve. Considering Native Americans have historically served in the armed forces at a higher per-capita rate than any other racial group, this sort of legislation is more than overdue. Wilma Pearl Mankiller, a Cherokee chief who was heavily involved in healthcare reform, would have wholeheartedly supported this bill. She would have recognized it as a necessary step toward equal treatment under the law. However, Mankiller would have also realized that the bill does not go far enough. Its focus on urban veterans leaves out a large portion of the individuals in need of care. She knew, from personal experience, that the situation on reservations was just as dire as that in cities. Wilma Pearl Mankiller would not only have championed the Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act but would have also fought to provide the same level of care to indigenous communities in rural areas.

Udall and Khanna’s bill is intended to correct the United States’ disgraceful mismanagement of the medical needs of indigenous veterans. The legislation concentrates on the seventy percent of Native American veterans who choose to live in urban centers after their time in the military. Most of these individuals are unable to access the urban I.H.S. system because the V.A. does not reimburse them for their visits. They are forced to rely on overcrowded Veterans Affairs hospitals run and staffed by non-indigenous people. Udall stated that the bill is intended to “ensure more Native veterans have equal access to timely, culturally-competent care regardless of where they choose to live after leaving their military service.” Culturally-competent care is doubly important for veterans because they often have more complicated psychological conditions than civilian patients. This type of care incorporates the beliefs, traditions, and values of the patients’ upbringing in the healing process. Indigenous veterans, living anywhere, should receive treatment equal to that of their white counterparts. The Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act, which has been on the Senate legislative calendar for over a year, is a slow but necessary move toward improvement.

The Health Care Access bill fails to address the concerns of the thirty percent of veterans who choose to reside in rural communities. These individuals are often underserved because of geographical barriers and insufficiently staffed I.H.S. programs. In remote areas, many indigenous veterans with disabilities are unable to travel to healthcare facilitates. Neither the I.H.S. nor the V.A. provides any transit service for these people. Unlike in urban environments, public transportation is rarely an option. Understaffed facilities worsen the situation because they often lack medical professionals specialized in veteran care. In Hopi veteran Vanissa Barnes-Saucedo’s case, the “I.H.S. helped her get the medications she needed to manage her PTSD, but staff members lacked practical knowledge related to veteran-specific issues.” This struggle seems to be the converse of that faced by urban veterans who are unable to find culturally-competent care in whitewashed V.A. facilities. It is the U.S. government’s legal responsibility to ensure that all indigenous veterans receive proper care. Since Udall and Khanna’s bill only assumes part of this responsibility, it does not come close to solving the problem of substandard care.

Wilma Pearl Mankiller would have supported the Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act, despite its shortcomings, because of her personal experience with trauma and medicine. She was in a car accident in 1979, which necessitated seventeen surgeries and years of physical therapy. This experience lead her to spend much of her time as Cherokee Chief “developing a comprehensive healthcare system” for her tribe. The time she spent as a leader and lobbyist acquainted her with the racial biases in the United States’ lawmaking process that lead to the holes in Native American healthcare. She would have realized that Udall and Khanna’s bill is an attempt to help the largest, most easily accessible, portion of the community in need. Even though it does not solve the problems of all Native American veterans, it does address the concerns of thousands of disgruntled people. Mankiller would have openly acknowledged that the bill ignores far too many individuals because of their location. So much of her life was spent dealing with rural health care issues that she would not have allowed them to go unrecognized. However, this recognition would likely follow her ardent endorsement of the bill. If Wilma Mankiller were still politically active in 2019, she would have fought for the healthcare rights of indigenous veterans living in both rural and urban environments.

The goals of the 2019 Health Care Access for Urban Native Veterans Act align with those historically supported by the late twentieth century Cherokee Chief Wilma Pearl Mankiller. Senator Udall and Representative Khanna’s bill is part of a progression toward a standardized system of appropriate care for all indigenous Veterans. Mankiller’s personal health concerns and passion for protecting indigenous peoples lead her to devote her life to a similar objective. She would have wished to include rural veterans in the legislation, but this would not have stopped her from standing behind it. Wilma Mankiller’s narrative suggests that she would have struggled unceasingly to provide proper healthcare to Native American veterans.