7 Week 7

Topic: Add Health data: variable creation and tabulation

This week's lesson will provide more background on variable creation and tabulation of variables.

7.1 Creating value labels

"Labeled" data are important for documentation of data sets. The labels can apply to different objects, e.g., columns (as we saw in the column labels used to "decode" the data set in AHwave1_v1.dta, Section 2.4), or to individual values of variables, e.g., the attribute labels of the variable h1gi1m:

AHwave1_v1_haven <- haven::read_dta("http://staff.washington.edu/phurvitz/csde502_winter_2021/data/AHwave1_v1.dta")

attributes(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi1m)$labels## (1) January (2) February (3) March (4) April (5) May (6) June (7) July (8) August

## 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

## (9) September (10) October (11) November (12) December (96) Refused

## 9 10 11 12 96Consider the difference between different file formats. Here we will save the data set, once as a CSV file and once an RDS file:

# use Sys.getenv("TEMP") to get the system temp dir to save the CSV and RDS files

tmpdir <- Sys.getenv("TEMP")

write.csv(x = AHwave1_v1_haven, file = file.path(tmpdir, "AHwave1_v1_haven.csv"), row.names = FALSE)

saveRDS(object = AHwave1_v1_haven, file = file.path(tmpdir, "AHwave1_v1_haven.RDS"))Then we will read them back in and investigate their structure. First, the CSV format:

AHwave1_v1_haven_csv <- read.csv(file = file.path(tmpdir, "AHwave1_v1_haven.csv"))What kind of object is this?

is(AHwave1_v1_haven_csv)## [1] "data.frame" "list" "oldClass" "vector"It is a simple data frame. What attributes does this data set have? Here we list the attributes and enumerate the first 6 elements of each attribute

AHwave1_v1_haven_csv %>%

attributes() %>%

map(~ head(.))## $names

## [1] "aid" "imonth" "iday" "iyear" "bio_sex" "h1gi1m"

##

## $class

## [1] "data.frame"

##

## $row.names

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6There are three attributes, names, which are the individual column names; class, indicating this is a data frame, and row.names, in this case a serial number 1 .. n.

Do the columns have any attributes?

AHwave1_v1_haven_csv$h1gi1m %>%

attributes() ## NULLNo, the columns have no attributes.

Now we will read in the RDS file:

AHwave1_v1_haven_rds <- readRDS(file = file.path(tmpdir, "AHwave1_v1_haven.RDS"))What kind of object is this?

is(AHwave1_v1_haven_rds)## [1] "tbl_df" "tbl" "data.frame" "list" "oldClass" "vector"It is a data frame--but an example of the tidyr subclass tibble; see the documentation

What attributes does this data set have?

AHwave1_v1_haven_rds %>%

attributes() %>%

map(~ head(.))## $label

## [1] "National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), 1994-200"

##

## $names

## [1] "aid" "imonth" "iday" "iyear" "bio_sex" "h1gi1m"

##

## $row.names

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6

##

## $class

## [1] "tbl_df" "tbl" "data.frame"The overall attributes are similar to the basic data frame, but there is an overall data set label, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), 1994-200 (sic).

We can also look at the attributes of specific columns:

AHwave1_v1_haven_rds$h1gi1m %>%

attributes()## $label

## [1] "S1Q1 BIRTH MONTH-W1"

##

## $format.stata

## [1] "%13.0f"

##

## $class

## [1] "haven_labelled" "vctrs_vctr" "double"

##

## $labels

## (1) January (2) February (3) March (4) April (5) May (6) June (7) July (8) August

## 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

## (9) September (10) October (11) November (12) December (96) Refused

## 9 10 11 12 96Here we see that all of the original column attributes were preserved when the data set was saved in RDS format.

Importantly, saving a data set in CSV format loses any built-in metadata, whereas saving in RDS format maintains the built-in metadata. For other plain text formats, metadata will not be maintained; for other formats, it is worth determining whether such metadata are maintained. If metadata are not maintained in the file structure of the data set, it will be important to maintain the metadata in an external format (e.g., text, PDF).

7.1.1 Creating factor variables

Factor variables are used in R to store categorical variables. These categorical variables can be nominal, in which each value is distinct and not ordered, such as race, classified as

- White

- Black/African American

- American Indian

- Asian/Pacific Islander

- other

Factor variables can be ordered, where there is a difference in amount or intensity, such as self-reported health status:

- Excellent

- Very good

- Good

- Fair

- Poor

Ordinal variables may or may not have equal intervals; for example, the "distance" between excellent and good health may not represent the same "distance" as the difference between good and fair health.

Structurally, factor variables are stored as integers that can be linked to text labels. Operationally, the use of factor variables is important in statistical modeling, so that the variables are handled correctly as being categorical.

Factor variables are created using the factor() or as_factor() functions. Here we will convert the self-reported general health variable (h1gh1) to a factor. First, let's look at the variable:

AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1 %>%

attributes()## $label

## [1] "S3Q1 GENERAL HEALTH-W1"

##

## $format.stata

## [1] "%14.0f"

##

## $class

## [1] "haven_labelled" "vctrs_vctr" "double"

##

## $labels

## (1) Excellent (2) Very good (3) Good (4) Fair (5) Poor (6) Refused (8) Don't know

## 1 2 3 4 5 6 8This shows that there are values 1 through 6 and 8, with coding indicated in the labels attribute. Using head() also reveals the structure of the variable, including the label for the variable itself as well as the coding of the variable values:

head(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1)## <labelled<double>[6]>: S3Q1 GENERAL HEALTH-W1

## [1] 3 4 4 4 3 3

##

## Labels:

## value label

## 1 (1) Excellent

## 2 (2) Very good

## 3 (3) Good

## 4 (4) Fair

## 5 (5) Poor

## 6 (6) Refused

## 8 (8) Don't knowHere we convert the variable to a factor:

AHwave1_v1_haven$health <- factor(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1)What is the result? We can see from the first few values; head() presents the values as well as the levels.

# look at the first few values of the factor variable

head(AHwave1_v1_haven$health)## [1] 3 4 4 4 3 3

## Levels: 1 2 3 4 5 6 8Although the levels are in numerical order, there are no meaningful labels. We use the labels = argument to assign labels to each level. Simultaneously, because the factor is ordered in the same order as the alphanumeric ordering of the attributes, we can set the ordering based on those attributes. Finally, we reverse the order of the levels so that better health has a higher position in the order.

# extract the labels from the column attribute

health_levels <- AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1 %>%

attributes() %>%

extract2("labels") %>%

names()

# create the factor variable

AHwave1_v1_haven$health <- factor(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1,

labels = health_levels,

ordered = TRUE) %>%

fct_relevel(rev)[Note that if the ordering is not alphanumeric, one should enter the list of values as ... labels = c("label1", "label2, ..., "labeln"), ordered = TRUE ... to enforce correct ordering.]

Let's compare the two variables through simple tabulation. Here is the "raw" variable:

# "raw" variable

(tab_h1gh1 <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

group_by(h1gh1) %>%

summarise(n = n()))## # A tibble: 7 x 2

## h1gh1 n

## <dbl+lbl> <int>

## 1 1 [(1) Excellent] 1847

## 2 2 [(2) Very good] 2608

## 3 3 [(3) Good] 1605

## 4 4 [(4) Fair] 408

## 5 5 [(5) Poor] 28

## 6 6 [(6) Refused] 3

## 7 8 [(8) Don't know] 5The "raw" variable shows that it is a labeled, double precision variable (<dbl+lbl>).

Now the factor variable:

# factor variable

(tab_health <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

group_by(health) %>%

summarise(n = n()))## # A tibble: 7 x 2

## health n

## <ord> <int>

## 1 (8) Don't know 5

## 2 (6) Refused 3

## 3 (5) Poor 28

## 4 (4) Fair 408

## 5 (3) Good 1605

## 6 (2) Very good 2608

## 7 (1) Excellent 1847The counts are the same, but for the factor variable, the <ord> additionally indicates the ordering of health levels. Note that the order is different because (1) Excellent should have the highest numerical value.

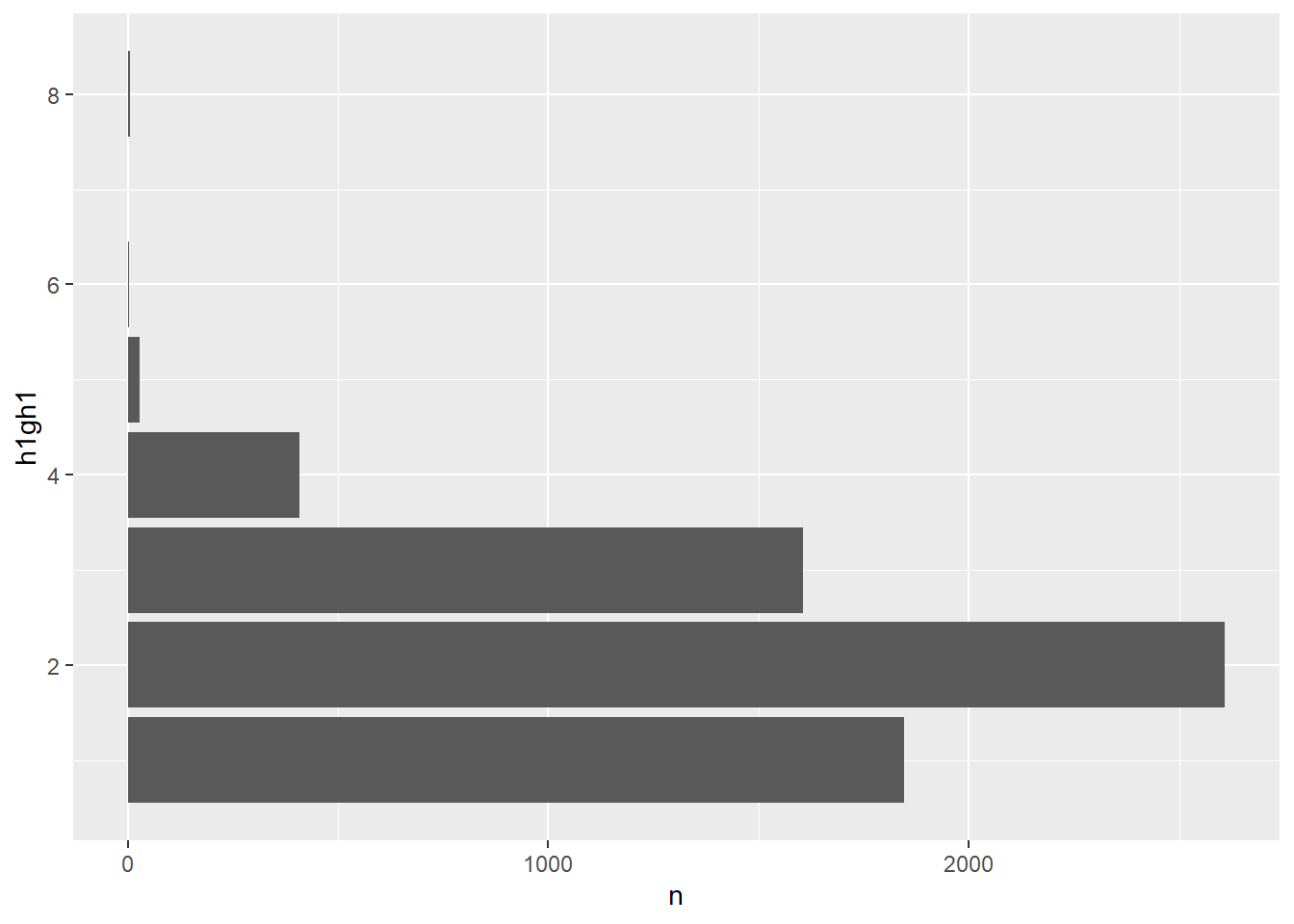

Bar plots also show the difference between the raw and factor variables. Here is a bar plot from the raw variable.

ggplot(data = tab_h1gh1, aes(x = h1gh1, y = n)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

coord_flip()

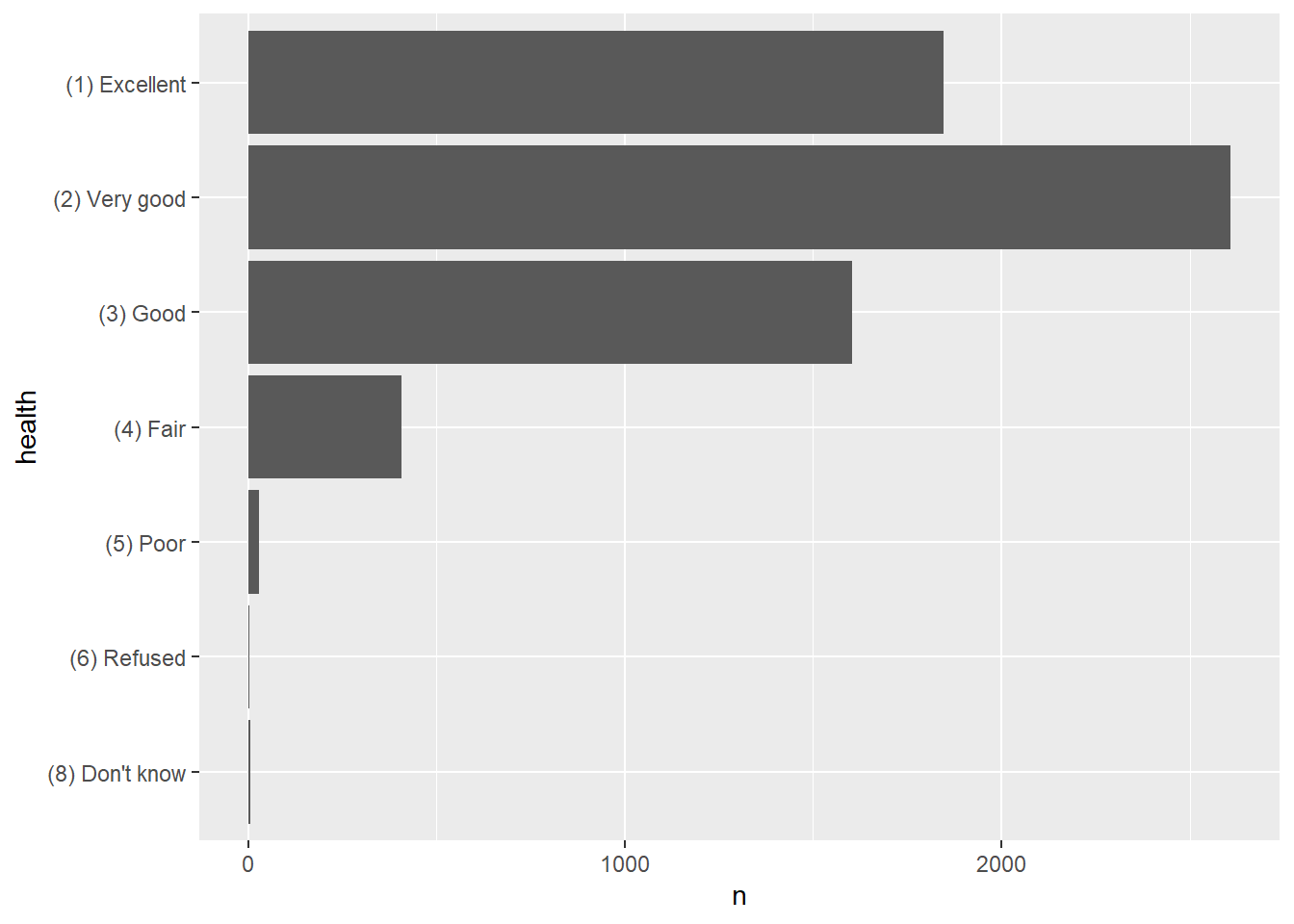

Because the numerical values have no special meaning, the bar plot uses its default method of displaying the axes. Here is the bar plot created with the factor variable, which shows informative labels at the correct position on the axes.

ggplot(data = tab_health, mapping = aes(x = health, y = n)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

coord_flip()

One of the potential down sides to using factor variables is that using the text values requires additional code. For example, to select (filter()) a subset of records, there are two methods. The first method uses the label. In this case because the factor is ordered, it is possible to use an ordinal comparison.

# filter for Excellent or Very good

y <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter (health <= "(2) Very good")

# tabulate

table(y$health)##

## (8) Don't know (6) Refused (5) Poor (4) Fair (3) Good (2) Very good (1) Excellent

## 5 3 28 408 1605 2608 0The other method is to use as_numeric() to specify the underlying numerical values. In this case, because the value of 2 indicated Very good, we can filter for health %>% as.numeric() <= 2.

x <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter(health %>% as.numeric() <= 2)Using unordered factor variables shows that more coding is involved in specifying values in filter() statements. For example, let's create a factor variable for the interviewer's observed single race variable:

# number of labels

nlabs <- length(unique(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi9))

# get the values, "as.numeric()"

obsrace_values <- AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi9 %>%

attributes() %>%

extract2("labels") %>%

as.numeric()

# get the labels, names()

obsrace_labels <- AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi9 %>%

attributes() %>%

extract2("labels") %>%

names()

# create the factor

AHwave1_v1_haven$obsrace <- factor(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi9,

levels = obsrace_values,

labels = obsrace_labels)Suppose we wanted to make a subset of only White and Black records, there are a few syntax methods:

Here, each value is explicitly named, using the | "or" operator

dat_wb1 <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter(obsrace == "(1) White" |

obsrace == "(2) Black/African American")

table(dat_wb1$obsrace)##

## (1) White (2) Black/African American (3) American Indian/Native American

## 4291 1601 0

## (4) Asian/Pacific Islander (5) Other (6) Refused

## 0 0 0

## (8) Don't know (9) Not applicable

## 0 0A different approach uses str_detect() with a regular expression to match any values of obsrace that contain the strings white or black in any upper/lower case combination.

dat_wb2 <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter(str_detect(obsrace, regex("white|black", ignore_case = TRUE)))

table(dat_wb2$obsrace)##

## (1) White (2) Black/African American (3) American Indian/Native American

## 4291 1601 0

## (4) Asian/Pacific Islander (5) Other (6) Refused

## 0 0 0

## (8) Don't know (9) Not applicable

## 0 0Finally, if we know the numeric values representing the factors, we can use those directly:

dat_wb3 <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter(obsrace %>% as.numeric() %in% c(1, 2))

table(dat_wb3$obsrace)##

## (1) White (2) Black/African American (3) American Indian/Native American

## 4291 1601 0

## (4) Asian/Pacific Islander (5) Other (6) Refused

## 0 0 0

## (8) Don't know (9) Not applicable

## 0 0The first method is the most verbose, requires the most code, and is probably the easiest to read. The other two methods may be easier to code (i.e., fewer keystrokes), but seem to be more difficult to interpret.

As above, care needs to be taken in saving the data set to a file. If the factor has text labels, those will be written to an output CSV file. When they are read back in, they will be treated as character values rather than factors. For example, the health variable we created is an ordered factor:

head(AHwave1_v1_haven$health)## [1] (3) Good (4) Fair (4) Fair (4) Fair (3) Good (3) Good

## Levels: (8) Don't know < (6) Refused < (5) Poor < (4) Fair < (3) Good < (2) Very good < (1) ExcellentBut when cycled through a write/read CSV cycle, the variable is not maintained as a factor.

write.csv(x = AHwave1_v1_haven, file = file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.csv"), row.names = FALSE)

y <- read.csv(file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.csv"))

head(y$health)## [1] "(3) Good" "(4) Fair" "(4) Fair" "(4) Fair" "(3) Good" "(3) Good"Additional work would be needed to re-establish it as a factor. Fortunately, the alphanumeric sorting order of the character strings is the logical order; without the numeric values, the ordering would need to be explicitly set. For example, the vector in desired sorting order "Excellent", "Very good", "Good", "Fair", "Poor", "Refused", "Don't know" sorts as Don't know, Excellent, Fair, Good, Poor, Refused, Very good), which is not the proper sorting order.

y$health <- factor(y$health,

labels = y$health %>% unique() %>% sort(),

ordered = TRUE)

head(y$health)## [1] (3) Good (4) Fair (4) Fair (4) Fair (3) Good (3) Good

## Levels: (1) Excellent < (2) Very good < (3) Good < (4) Fair < (5) Poor < (6) Refused < (8) Don't knowIf you save the data set as RDS, the factor and other structures are maintained.

write_rds(x = AHwave1_v1_haven, file = file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.Rds"))

z <- readRDS(file = file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.Rds"))

head(z$health)## [1] (3) Good (4) Fair (4) Fair (4) Fair (3) Good (3) Good

## Levels: (8) Don't know < (6) Refused < (5) Poor < (4) Fair < (3) Good < (2) Very good < (1) Excellent7.1.2 Creating attributes

In addition to creating factors, which can serve in some capacity as self-documenting (i.e., the value labels should be at least somewhat self-explanatory), we can create attributes as we have seen with the Stata .dta files.

Let's start with the CSV file, which we know was stripped of its descriptive attributes:

y <- read.csv(file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.csv"))

y %>% attributes() %>% map(~ head(.))## $names

## [1] "aid" "imonth" "iday" "iyear" "bio_sex" "h1gi1m"

##

## $class

## [1] "data.frame"

##

## $row.names

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6First, an attribute of the data frame itself:

attributes(y)$label <- "National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), 1994-2000 with some variable additions"... which we can verify:

y %>% attributes() %>% extract("label")## $label

## [1] "National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), 1994-2000 with some variable additions"Next, attributes for the health and obsrace variables, documenting the variables and values:

# label for health

attributes(y$health)$label <- "General health from public Add Health Wave 1 Section 3 question 1"

# values for health

attributes(y$health)$levels <- c("(1) Excellent", "(2) Very good", "(3) Good", "(4) Fair", "(5) Poor", "(6) Refused", "(8) Don't know")

# label for obsrace

attributes(y$obsrace)$label <- "Interviewer observation of race from public Add Health Wave 1 Section 1 question 9"

# values for obsrace

attributes(y$obsrace)$levels <- c("(1) White", "(2) Black/African American", "(3) American Indian/Native American", "(4) Asian/Pacific Islander", "(5) Other", "(6) Refused", "(8) Don't know", "(9) Not applicable")Verify these were created:

y$health %>% attributes()## $label

## [1] "General health from public Add Health Wave 1 Section 3 question 1"

##

## $levels

## [1] "(1) Excellent" "(2) Very good" "(3) Good" "(4) Fair" "(5) Poor" "(6) Refused"

## [7] "(8) Don't know"y$obsrace %>% attributes()## $label

## [1] "Interviewer observation of race from public Add Health Wave 1 Section 1 question 9"

##

## $levels

## [1] "(1) White" "(2) Black/African American"

## [3] "(3) American Indian/Native American" "(4) Asian/Pacific Islander"

## [5] "(5) Other" "(6) Refused"

## [7] "(8) Don't know" "(9) Not applicable"The same caveats apply to saving the data frame to files.

7.2 Tabulation

We have seen a few examples of tabulation in previous exercises (Sections 2.4.2.5, 3.2, 4.2.1.2.1). This section will give a more complete treatment using the Add Health data as an example.

7.2.1 Raw counts

The most basic tabulations simply give the count of observations in different strata. Those strata can be based on numeric ratio or interval data, using functions such as cut() or BAMMtools::getJenksBreaks(), nominal data (such as the Add Health interviewer's observation of respondents' single race), or ordinal data (such as the self-reported health status). We will use examples of each type of data.

First, this code will load the full Add Health data set, which includes additional variables not present in the data set we have used previously.

# download and unzip the larger data set

myUrl <- "http://staff.washington.edu/phurvitz/csde502_winter_2021/data/21600-0001-Data.dta.zip"

# zipfile in $temp

zipfile <- file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), basename(myUrl))

# dta file in $temp

dtafile <- tools::file_path_sans_ext(zipfile)

# check if the dta file exists

if(!file.exists(dtafile)){

# if the dta file doesn't exist, check for the zip file

# check if the zip file exists, download if necessary

if(!file.exists(zipfile)){

curl::curl_download(url = myUrl, destfile = zipfile)

}

# unzip the downloaded zip file

unzip(zipfile = zipfile, exdir = Sys.getenv("TEMP"))

}

# if the data set has not been read, read it in

if(!exists("ahcomplete")){

ahcomplete <- haven::read_dta(dtafile)

}

# lowercase column names

colnames(ahcomplete) %<>% str_to_lower()Present the metadata (variable names and labels):

ahcomplete_metadata <- bind_cols(

varname = colnames(ahcomplete),

varlabel = ahcomplete %>% map(~ attributes(.)$label) %>% unlist()

)

DT::datatable(ahcomplete_metadata)Let's look at body mass index (BMI) data, which uses weight and height values. We find the variables representing weight and height from the metadata above. We need to determine if there are any invalid values:

attributes(ahcomplete$h1gh59a)$labels## (4) 4 feet (5) 5 feet (6) 6 feet (96) Refused (98) Don't know

## 4 5 6 96 98attributes(ahcomplete$h1gh59b)$labels## (0) 0 inches (1) 1 inch (2) 2 inches (3) 3 inches (4) 4 inches

## 0 1 2 3 4

## (5) 5 inches (6) 6 inches (7) 7 inches (8) 8 inches (9) 9 inches

## 5 6 7 8 9

## (10) 10 inches (11) 11 inches (96) Refused (98) Don't know (99) Not applicable

## 10 11 96 98 99attributes(ahcomplete$h1gh60)$labels## (996) Refused (998) Don't know (999) Not applicable

## 996 998 999First, we need to select the variables representing feet and inches, then filter out invalid heights (> 90) and weights (> 900) identified above, and finally calculate height in m, weight in kg, and BMI (\(\frac{weight\_{kg}}{{height\_m}^2}\)). For future use we will also select self-reported health and interviewer observed race as factors.

# make the data frmae

htwt <- ahcomplete %>%

# select columns

select(feet = h1gh59a,

inches = h1gh59b,

weight_lb = h1gh60,

health = h1gh1,

obsrace = h1gi9) %>%

# filter for valid values

filter(feet < 90 & inches < 90 & weight_lb < 900) %>%

# calculate

mutate(height_m = (feet * 12 + inches) / 39.37008,

weight_kg = weight_lb / 2.205,

BMI = weight_kg / height_m^2)

# factor: get values and labels

healthvals <- htwt$health %>% attributes() %>% extract2("labels") %>% as.numeric()

healthlabs <- htwt$health %>% attributes() %>% extract2("labels") %>% names()

racevals <- htwt$obsrace %>% attributes() %>% extract2("labels") %>% as.numeric()

racelabs <- htwt$obsrace %>% attributes() %>% extract2("labels") %>% names()

htwt %<>%

mutate(health = factor(health,

levels = healthvals,

labels = healthlabs),

obsrace = factor(obsrace,

levels = racevals,

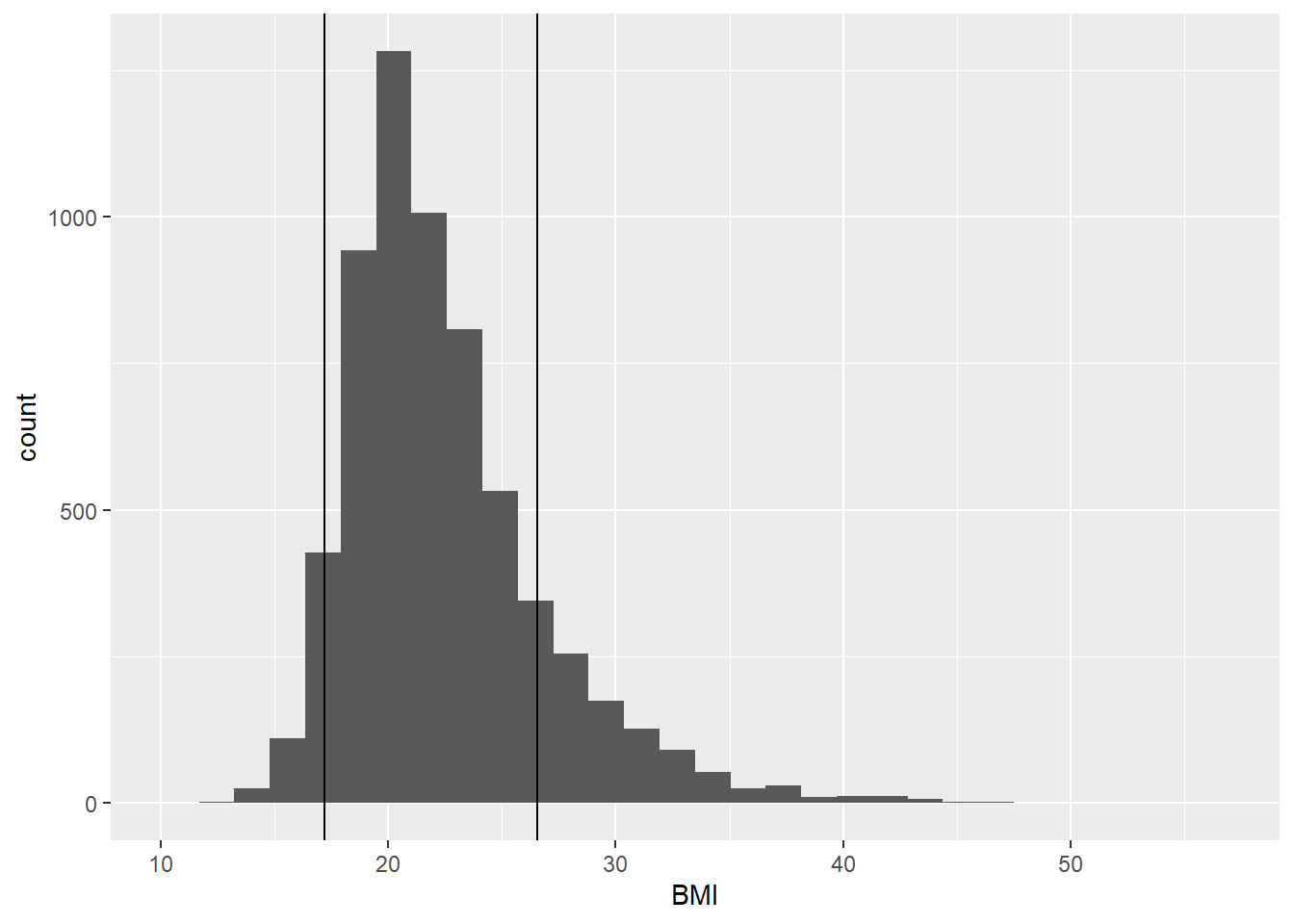

labels = racelabs))A histogram shows the distribution of BMI for the respondents with vertical lines at the 5th and 85th percentile. This range is generally considered "normal" or "healthy" according to the CDC, although for a sample with varying age, sex, height, and weight ranges, it is difficult to interpret. Nevertheless the cut points can serve the purpose of demonstration.

# get the 5th & 85th percentile

bmibreaks <- quantile(x = htwt$BMI, probs = c(0.05, 0.85))

ggplot(htwt, aes(x = BMI)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 30) +

geom_vline(xintercept = bmibreaks)

We assign the BMI class using these cut points, with cut() breaks at the minimum, 5%, 85%, and maximum BMI, and also assign labels and set ordering:

htwt %<>%

mutate(bmiclass = cut(x = BMI,

breaks = c(min(BMI), bmibreaks, max(BMI)),

labels = c("underweight", "normal", "overweight"),

include.lowest = TRUE) %>%

factor(ordered = TRUE))The tabulation of count of respondents by weight class can be generated with the base R function table() or dplyr functions group_by() and summarise().

# base R

table(htwt$bmiclass, useNA = "ifany")##

## underweight normal overweight

## 324 5023 944# tidyR

htwt %>%

group_by(bmiclass) %>%

summarise(n = n()) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")| bmiclass | n |

|---|---|

| underweight | 324 |

| normal | 5023 |

| overweight | 944 |

For variables that are already nominal or ordinal factors, tabulations can be made directly. Because these were converted to factors, the correct labels will show, rather than simple numeric values.

htwt %>%

group_by(health) %>%

summarise(n = n()) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")| health | n |

|---|---|

|

1803 |

|

2541 |

|

1531 |

|

389 |

|

26 |

|

1 |

htwt %>%

group_by(obsrace) %>%

summarise(n = n()) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")| obsrace | n |

|---|---|

|

4184 |

|

1525 |

|

68 |

|

230 |

|

280 |

|

1 |

|

3 |

7.2.2 Proportions/percentages

Proportions and percentages can be added to tabulations for greater interpretability. Using base R, the prop_table() function can be used as a wrapper around table() to generate proportions, optionally multiplying by 100 to generate a percentage. Remember to round as needed. For example:

round(prop.table(table(htwt$bmiclass)), 2)##

## underweight normal overweight

## 0.05 0.80 0.15round(prop.table(table(htwt$bmiclass)) * 100, 0)##

## underweight normal overweight

## 5 80 15Not surprisingly, the BMI classes show 5% underweight and 15% overweight, because that is how the stratification was defined.

The tidyR version requires a bit more coding but provides a more readable output. Because the percent sign is a special character, we enclose it in back ticks, %. Here we generate a tabulation of observed race.

htwt %>%

group_by(obsrace) %>%

summarise(n = n()) %>%

mutate(`%` = n / sum(n) * 100) %>%

mutate(`%` = `%` %>% round(1)) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")| obsrace | n | % |

|---|---|---|

|

4184 | 66.5 |

|

1525 | 24.2 |

|

68 | 1.1 |

|

230 | 3.7 |

|

280 | 4.5 |

|

1 | 0.0 |

|

3 | 0.0 |

7.2.3 Stratified tabulation

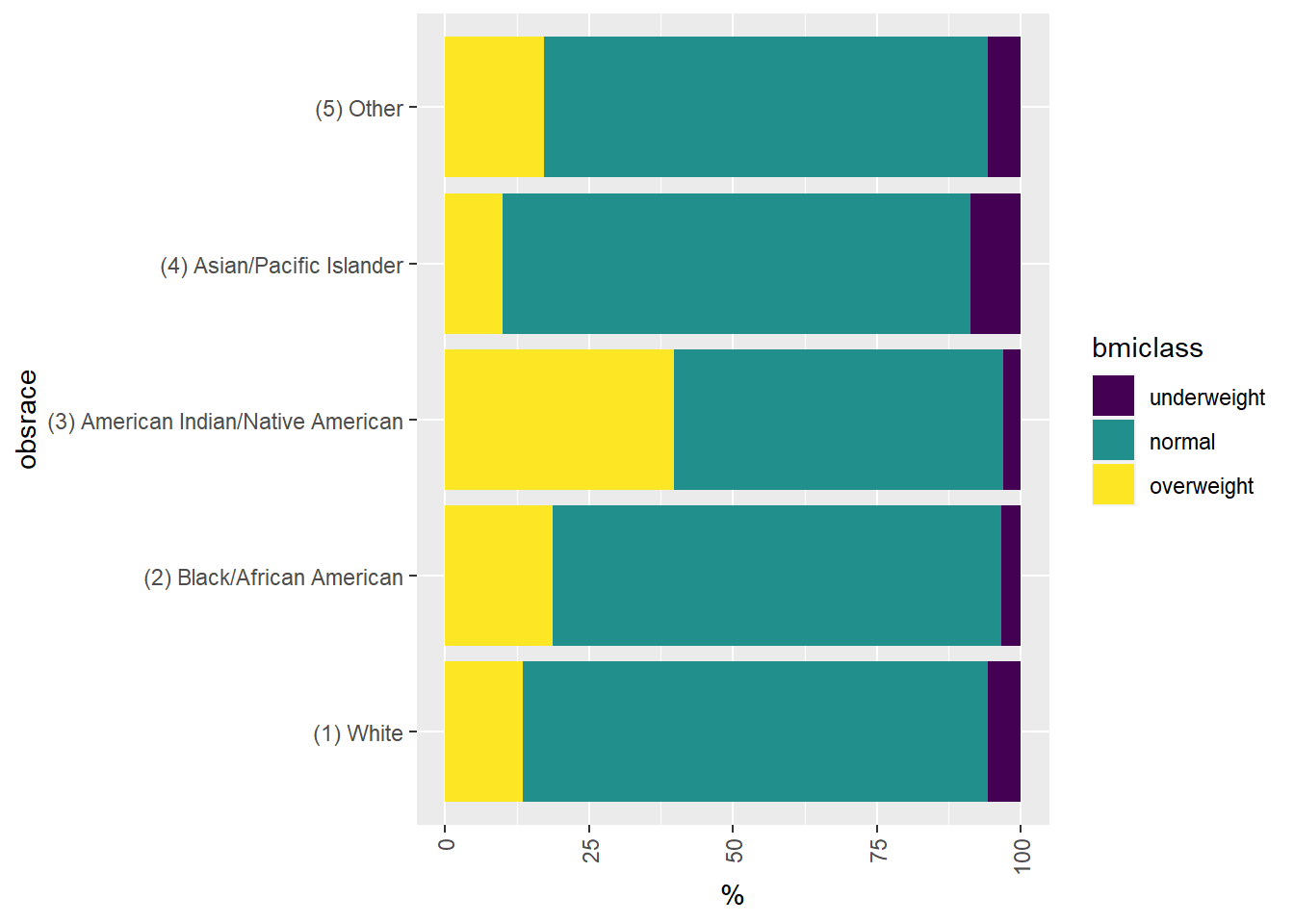

Tabulations can be generated using multiple variables. Here we will examine BMI and race as well as BMI and health. The percentages sum to 100 based on the order of the grouping.

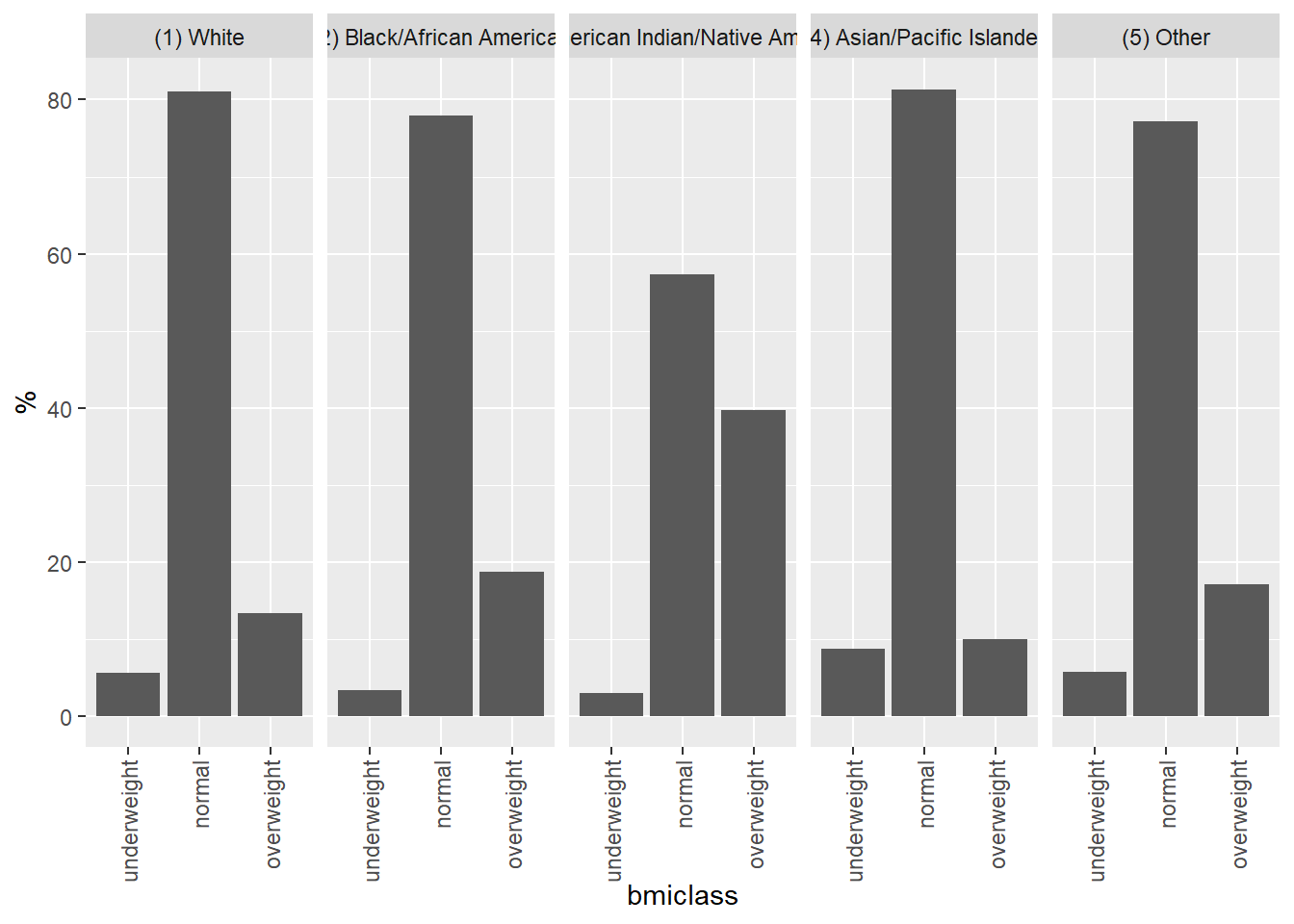

Here, we see the relative percent of underweight, normal, and overweight within each race class:

htwt %>%

group_by(obsrace,

bmiclass) %>%

summarise(n = n(), .groups = "drop_last") %>%

mutate(`%` = n / sum(n) * 100) %>%

mutate(`%` = `%` %>% round(1)) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")| obsrace | bmiclass | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

underweight | 234 | 5.6 |

|

normal | 3389 | 81.0 |

|

overweight | 561 | 13.4 |

|

underweight | 52 | 3.4 |

|

normal | 1188 | 77.9 |

|

overweight | 285 | 18.7 |

|

underweight | 2 | 2.9 |

|

normal | 39 | 57.4 |

|

overweight | 27 | 39.7 |

|

underweight | 20 | 8.7 |

|

normal | 187 | 81.3 |

|

overweight | 23 | 10.0 |

|

underweight | 16 | 5.7 |

|

normal | 216 | 77.1 |

|

overweight | 48 | 17.1 |

|

normal | 1 | 100.0 |

|

normal | 3 | 100.0 |

And here we see the relative percent of different race groups within each BMI class.

htwt %>%

group_by(bmiclass,

obsrace) %>%

summarise(n = n(), .groups = "drop_last") %>%

mutate(`%` = n / sum(n) * 100) %>%

mutate(`%` = `%` %>% round(1)) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")| bmiclass | obsrace | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| underweight |

|

234 | 72.2 |

| underweight |

|

52 | 16.0 |

| underweight |

|

2 | 0.6 |

| underweight |

|

20 | 6.2 |

| underweight |

|

16 | 4.9 |

| normal |

|

3389 | 67.5 |

| normal |

|

1188 | 23.7 |

| normal |

|

39 | 0.8 |

| normal |

|

187 | 3.7 |

| normal |

|

216 | 4.3 |

| normal |

|

1 | 0.0 |

| normal |

|

3 | 0.1 |

| overweight |

|

561 | 59.4 |

| overweight |

|

285 | 30.2 |

| overweight |

|

27 | 2.9 |

| overweight |

|

23 | 2.4 |

| overweight |

|

48 | 5.1 |

Even though the n values are the same in the two tables (e.g., underweight White n = 234), the percentages are different due to grouping. That is, the percent of underweight persons among the White race stratum is different from the percent of White persons within the underweight stratum. Proper grouping is critical to answer specific questions about the data.

Another way to understand the data, preferred by some, would be to make a graph. For example, BMI by race:

bmi_race <- htwt %>%

group_by(obsrace,

bmiclass) %>%

summarise(n = n(), .groups = "drop_last") %>%

mutate(`%` = n / sum(n) * 100) %>%

filter(!str_detect(obsrace, regex("refused|know", ignore_case = TRUE)))

ggplot(data = bmi_race, mapping = aes(x = bmiclass, y = `%`)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, vjust = 0.5, hjust=1)) +

facet_grid(~obsrace)

ggplot(data = bmi_race, mapping = aes(x = obsrace, y = `%`, fill = bmiclass)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

coord_flip() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, vjust = 0.5, hjust=1))

7.3 Source code

cat(readLines(con = "07-week07.Rmd"), sep = '\n')# Week 7 {#week7}

```{r, echo=FALSE, warning=FALSE, message=FALSE}

library(tidyverse)

library(magrittr)

library(knitr)

library(kableExtra)

library(readstata13)

library(haven)

library(pdftools)

library(curl)

library(ggplot2)

```

<h2>Topic: Add Health data: variable creation and tabulation</h2>

This week's lesson will provide more background on variable creation and tabulation of variables.

## Creating value labels

"Labeled" data are important for documentation of data sets. The labels can apply to different objects, e.g., columns (as we saw in the column labels used to "decode" the data set in `AHwave1_v1.dta`, Section \@ref(tidyverse)), or to individual values of variables, e.g., the attribute `labels` of the variable `h1gi1m`:

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven <- haven::read_dta("http://staff.washington.edu/phurvitz/csde502_winter_2021/data/AHwave1_v1.dta")

attributes(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi1m)$labels

```

Consider the difference between different file formats. Here we will save the data set, once as a CSV file and once an RDS file:

```{r}

# use Sys.getenv("TEMP") to get the system temp dir to save the CSV and RDS files

tmpdir <- Sys.getenv("TEMP")

write.csv(x = AHwave1_v1_haven, file = file.path(tmpdir, "AHwave1_v1_haven.csv"), row.names = FALSE)

saveRDS(object = AHwave1_v1_haven, file = file.path(tmpdir, "AHwave1_v1_haven.RDS"))

```

Then we will read them back in and investigate their structure. First, the CSV format:

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven_csv <- read.csv(file = file.path(tmpdir, "AHwave1_v1_haven.csv"))

```

What kind of object is this?

```{r}

is(AHwave1_v1_haven_csv)

```

It is a simple data frame. What attributes does this data set have? Here we list the attributes and enumerate the first 6 elements of each attribute

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven_csv %>%

attributes() %>%

map(~ head(.))

```

There are three attributes, `names`, which are the individual column names; `class`, indicating this is a data frame, and `row.names`, in this case a serial number 1 .. n.

Do the columns have any attributes?

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven_csv$h1gi1m %>%

attributes()

```

No, the columns have no attributes.

Now we will read in the RDS file:

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven_rds <- readRDS(file = file.path(tmpdir, "AHwave1_v1_haven.RDS"))

```

What kind of object is this?

```{r}

is(AHwave1_v1_haven_rds)

```

It is a data frame--but an example of the `tidyr` subclass `tibble`; see the [documentation](https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/tibble)

What attributes does this data set have?

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven_rds %>%

attributes() %>%

map(~ head(.))

```

The overall attributes are similar to the basic data frame, but there is an overall data set label, ``r AHwave1_v1_haven_rds %>% attributes() %>% extract("label")`` (_sic_).

We can also look at the attributes of specific columns:

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven_rds$h1gi1m %>%

attributes()

```

Here we see that all of the original column attributes were preserved when the data set was saved in RDS format.

__Importantly__, saving a data set in CSV format loses any built-in metadata, whereas saving in RDS format maintains the built-in metadata. For other plain text formats, metadata will not be maintained; for other formats, it is worth determining whether such metadata are maintained. If metadata are not maintained in the file structure of the data set, it will be important to maintain the metadata in an external format (e.g., text, PDF).

### Creating factor variables

Factor variables are used in R to store categorical variables. These categorical variables can be nominal, in which each value is distinct and not ordered, such as race, classified as

* White

* Black/African American

* American Indian

* Asian/Pacific Islander

* other

Factor variables can be ordered, where there is a difference in amount or intensity, such as self-reported health status:

1. Excellent

1. Very good

1. Good

1. Fair

1. Poor

Ordinal variables may or may not have equal intervals; for example, the "distance" between excellent and good health may not represent the same "distance" as the difference between good and fair health.

Structurally, factor variables are stored as integers that can be linked to text labels. Operationally, __the use of factor variables is important in statistical modeling, so that the variables are handled correctly as being categorical__.

Factor variables are created using the `factor()` or `as_factor()` functions. Here we will convert the self-reported general health variable (`h1gh1`) to a factor. First, let's look at the variable:

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1 %>%

attributes()

```

This shows that there are values 1 through 6 and 8, with coding indicated in the `labels` attribute. Using `head()` also reveals the structure of the variable, including the label for the variable itself as well as the coding of the variable values:

```{r}

head(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1)

```

Here we convert the variable to a factor:

```{r}

AHwave1_v1_haven$health <- factor(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1)

```

What is the result? We can see from the first few values; `head()` presents the values as well as the levels.

```{r}

# look at the first few values of the factor variable

head(AHwave1_v1_haven$health)

```

Although the levels are in numerical order, there are no meaningful labels. We use the `labels = ` argument to assign labels to each level. Simultaneously, because the factor is ordered in the same order as the alphanumeric ordering of the attributes, we can set the ordering based on those attributes. Finally, we reverse the order of the levels so that better health has a higher position in the order.

```{r}

# extract the labels from the column attribute

health_levels <- AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1 %>%

attributes() %>%

extract2("labels") %>%

names()

# create the factor variable

AHwave1_v1_haven$health <- factor(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gh1,

labels = health_levels,

ordered = TRUE) %>%

fct_relevel(rev)

```

_[Note that if the ordering is not alphanumeric, one should enter the list of values as `... labels = c("label1", "label2, ..., "labeln"), ordered = TRUE ...` to enforce correct ordering.]_

Let's compare the two variables through simple tabulation. Here is the "raw" variable:

```{r}

# "raw" variable

(tab_h1gh1 <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

group_by(h1gh1) %>%

summarise(n = n()))

```

The "raw" variable shows that it is a labeled, double precision variable (`<dbl+lbl>`).

Now the factor variable:

```{r}

# factor variable

(tab_health <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

group_by(health) %>%

summarise(n = n()))

```

The counts are the same, but for the factor variable, the `<ord>` additionally indicates the ordering of health levels. Note that the order is different because `(1) Excellent` should have the highest numerical value.

Bar plots also show the difference between the raw and factor variables. Here is a bar plot from the raw variable.

```{r, warning=FALSE, message=FALSE}

ggplot(data = tab_h1gh1, aes(x = h1gh1, y = n)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

coord_flip()

```

Because the numerical values have no special meaning, the bar plot uses its default method of displaying the axes. Here is the bar plot created with the factor variable, which shows informative labels at the correct position on the axes.

```{r}

ggplot(data = tab_health, mapping = aes(x = health, y = n)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

coord_flip()

```

One of the potential down sides to using factor variables is that using the text values requires additional code. For example, to select (`filter()`) a subset of records, there are two methods. The first method uses the label. In this case because the factor is ordered, it is possible to use an ordinal comparison.

```{r}

# filter for Excellent or Very good

y <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter (health <= "(2) Very good")

# tabulate

table(y$health)

```

The other method is to use `as_numeric()` to specify the underlying numerical values. In this case, because the value of 2 indicated `Very good`, we can filter for `health %>% as.numeric() <= 2`.

```{r}

x <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter(health %>% as.numeric() <= 2)

```

Using unordered factor variables shows that more coding is involved in specifying values in `filter()` statements. For example, let's create a factor variable for the interviewer's observed single race variable:

```{r}

# number of labels

nlabs <- length(unique(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi9))

# get the values, "as.numeric()"

obsrace_values <- AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi9 %>%

attributes() %>%

extract2("labels") %>%

as.numeric()

# get the labels, names()

obsrace_labels <- AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi9 %>%

attributes() %>%

extract2("labels") %>%

names()

# create the factor

AHwave1_v1_haven$obsrace <- factor(AHwave1_v1_haven$h1gi9,

levels = obsrace_values,

labels = obsrace_labels)

```

Suppose we wanted to make a subset of only White and Black records, there are a few syntax methods:

Here, each value is explicitly named, using the `|` "or" operator

```{r}

dat_wb1 <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter(obsrace == "(1) White" |

obsrace == "(2) Black/African American")

table(dat_wb1$obsrace)

```

A different approach uses `str_detect()` with a regular expression to match any values of `obsrace` that contain the strings `white` or `black` in any upper/lower case combination.

```{r}

dat_wb2 <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter(str_detect(obsrace, regex("white|black", ignore_case = TRUE)))

table(dat_wb2$obsrace)

```

Finally, if we know the numeric values representing the factors, we can use those directly:

```{r}

dat_wb3 <- AHwave1_v1_haven %>%

filter(obsrace %>% as.numeric() %in% c(1, 2))

table(dat_wb3$obsrace)

```

The first method is the most verbose, requires the most code, and is probably the easiest to read. The other two methods may be easier to code (i.e., fewer keystrokes), but seem to be more difficult to interpret.

As above, care needs to be taken in saving the data set to a file. If the factor has text labels, those will be written to an output CSV file. When they are read back in, they will be treated as character values rather than factors. For example, the `health` variable we created is an ordered factor:

```{r}

head(AHwave1_v1_haven$health)

```

But when cycled through a write/read CSV cycle, the variable is not maintained as a factor.

```{r}

write.csv(x = AHwave1_v1_haven, file = file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.csv"), row.names = FALSE)

y <- read.csv(file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.csv"))

head(y$health)

```

Additional work would be needed to re-establish it as a factor. Fortunately, the alphanumeric sorting order of the character strings is the logical order; without the numeric values, the ordering would need to be explicitly set. For example, the vector in desired sorting order `"Excellent", "Very good", "Good", "Fair", "Poor", "Refused", "Don't know"` sorts as ``r c("Excellent", "Very good", "Good", "Fair", "Poor", "Refused", "Don't know") %>% sort()``), which is not the proper sorting order.

```{r}

y$health <- factor(y$health,

labels = y$health %>% unique() %>% sort(),

ordered = TRUE)

head(y$health)

```

If you save the data set as RDS, the factor and other structures are maintained.

```{r}

write_rds(x = AHwave1_v1_haven, file = file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.Rds"))

z <- readRDS(file = file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.Rds"))

head(z$health)

```

### Creating attributes

In addition to creating factors, which can serve in some capacity as self-documenting (i.e., the value labels should be at least somewhat self-explanatory), we can create attributes as we have seen with the Stata `.dta` files.

Let's start with the CSV file, which we know was stripped of its descriptive attributes:

```{r}

y <- read.csv(file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), "foo.csv"))

y %>% attributes() %>% map(~ head(.))

```

First, an attribute of the data frame itself:

```{r}

attributes(y)$label <- "National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), 1994-2000 with some variable additions"

```

... which we can verify:

```{r}

y %>% attributes() %>% extract("label")

```

Next, attributes for the `health` and `obsrace` variables, documenting the variables and values:

```{r}

# label for health

attributes(y$health)$label <- "General health from public Add Health Wave 1 Section 3 question 1"

# values for health

attributes(y$health)$levels <- c("(1) Excellent", "(2) Very good", "(3) Good", "(4) Fair", "(5) Poor", "(6) Refused", "(8) Don't know")

# label for obsrace

attributes(y$obsrace)$label <- "Interviewer observation of race from public Add Health Wave 1 Section 1 question 9"

# values for obsrace

attributes(y$obsrace)$levels <- c("(1) White", "(2) Black/African American", "(3) American Indian/Native American", "(4) Asian/Pacific Islander", "(5) Other", "(6) Refused", "(8) Don't know", "(9) Not applicable")

```

Verify these were created:

```{r}

y$health %>% attributes()

y$obsrace %>% attributes()

```

The same caveats apply to saving the data frame to files.

## Tabulation

We have seen a few examples of tabulation in previous exercises (Sections \@ref(summarizingaggregating-data), \@ref(tables-in-r-markdown), \@ref(default-values-for-arguments)). This section will give a more complete treatment using the Add Health data as an example.

### Raw counts

The most basic tabulations simply give the count of observations in different strata. Those strata can be based on numeric ratio or interval data, using functions such as `cut()` or `BAMMtools::getJenksBreaks()`, nominal data (such as the Add Health interviewer's observation of respondents' single race), or ordinal data (such as the self-reported health status). We will use examples of each type of data.

First, this code will load the full Add Health data set, which includes additional variables not present in the data set we have used previously.

```{r}

# download and unzip the larger data set

myUrl <- "http://staff.washington.edu/phurvitz/csde502_winter_2021/data/21600-0001-Data.dta.zip"

# zipfile in $temp

zipfile <- file.path(Sys.getenv("TEMP"), basename(myUrl))

# dta file in $temp

dtafile <- tools::file_path_sans_ext(zipfile)

# check if the dta file exists

if(!file.exists(dtafile)){

# if the dta file doesn't exist, check for the zip file

# check if the zip file exists, download if necessary

if(!file.exists(zipfile)){

curl::curl_download(url = myUrl, destfile = zipfile)

}

# unzip the downloaded zip file

unzip(zipfile = zipfile, exdir = Sys.getenv("TEMP"))

}

# if the data set has not been read, read it in

if(!exists("ahcomplete")){

ahcomplete <- haven::read_dta(dtafile)

}

# lowercase column names

colnames(ahcomplete) %<>% str_to_lower()

```

Present the metadata (variable names and labels):

```{r}

ahcomplete_metadata <- bind_cols(

varname = colnames(ahcomplete),

varlabel = ahcomplete %>% map(~ attributes(.)$label) %>% unlist()

)

DT::datatable(ahcomplete_metadata)

```

\

Let's look at body mass index (BMI) data, which uses weight and height values. We find the variables representing weight and height from the metadata above. We need to determine if there are any invalid values:

```{r}

attributes(ahcomplete$h1gh59a)$labels

attributes(ahcomplete$h1gh59b)$labels

attributes(ahcomplete$h1gh60)$labels

```

First, we need to select the variables representing feet and inches, then filter out invalid heights (> 90) and weights (> 900) identified above, and finally calculate height in m, weight in kg, and BMI ($\frac{weight\_{kg}}{{height\_m}^2}$). For future use we will also select self-reported health and interviewer observed race as factors.

```{r}

# make the data frmae

htwt <- ahcomplete %>%

# select columns

select(feet = h1gh59a,

inches = h1gh59b,

weight_lb = h1gh60,

health = h1gh1,

obsrace = h1gi9) %>%

# filter for valid values

filter(feet < 90 & inches < 90 & weight_lb < 900) %>%

# calculate

mutate(height_m = (feet * 12 + inches) / 39.37008,

weight_kg = weight_lb / 2.205,

BMI = weight_kg / height_m^2)

# factor: get values and labels

healthvals <- htwt$health %>% attributes() %>% extract2("labels") %>% as.numeric()

healthlabs <- htwt$health %>% attributes() %>% extract2("labels") %>% names()

racevals <- htwt$obsrace %>% attributes() %>% extract2("labels") %>% as.numeric()

racelabs <- htwt$obsrace %>% attributes() %>% extract2("labels") %>% names()

htwt %<>%

mutate(health = factor(health,

levels = healthvals,

labels = healthlabs),

obsrace = factor(obsrace,

levels = racevals,

labels = racelabs))

```

A histogram shows the distribution of BMI for the respondents with vertical lines at the 5th and 85th percentile. This range is generally considered "normal" or "healthy" according to the CDC, although for a sample with varying age, sex, height, and weight ranges, it is difficult to interpret. Nevertheless the cut points can serve the purpose of demonstration.

```{r}

# get the 5th & 85th percentile

bmibreaks <- quantile(x = htwt$BMI, probs = c(0.05, 0.85))

ggplot(htwt, aes(x = BMI)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 30) +

geom_vline(xintercept = bmibreaks)

```

We assign the BMI class using these cut points, with `cut()` breaks at the minimum, 5%, 85%, and maximum BMI, and also assign labels and set ordering:

```{r}

htwt %<>%

mutate(bmiclass = cut(x = BMI,

breaks = c(min(BMI), bmibreaks, max(BMI)),

labels = c("underweight", "normal", "overweight"),

include.lowest = TRUE) %>%

factor(ordered = TRUE))

```

The tabulation of count of respondents by weight class can be generated with the base R function `table()` or `dplyr` functions `group_by()` and `summarise()`.

```{r}

# base R

table(htwt$bmiclass, useNA = "ifany")

```

```{r}

# tidyR

htwt %>%

group_by(bmiclass) %>%

summarise(n = n()) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")

```

For variables that are already nominal or ordinal factors, tabulations can be made directly. Because these were converted to factors, the correct labels will show, rather than simple numeric values.

```{r}

htwt %>%

group_by(health) %>%

summarise(n = n()) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")

```

```{r}

htwt %>%

group_by(obsrace) %>%

summarise(n = n()) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")

```

### Proportions/percentages

Proportions and percentages can be added to tabulations for greater interpretability. Using base R, the `prop_table()` function can be used as a wrapper around `table()` to generate proportions, optionally multiplying by 100 to generate a percentage. Remember to round as needed. For example:

```{r}

round(prop.table(table(htwt$bmiclass)), 2)

round(prop.table(table(htwt$bmiclass)) * 100, 0)

```

Not surprisingly, the BMI classes show 5% underweight and 15% overweight, because that is how the stratification was defined.

The `tidyR` version requires a bit more coding but provides a more readable output. Because the percent sign is a special character, we enclose it in back ticks, ``%``. Here we generate a tabulation of observed race.

```{r}

htwt %>%

group_by(obsrace) %>%

summarise(n = n()) %>%

mutate(`%` = n / sum(n) * 100) %>%

mutate(`%` = `%` %>% round(1)) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")

```

### Stratified tabulation

Tabulations can be generated using multiple variables. Here we will examine BMI and race as well as BMI and health. The percentages sum to 100 based on the order of the grouping.

Here, we see the relative percent of underweight, normal, and overweight within each race class:

```{r}

htwt %>%

group_by(obsrace,

bmiclass) %>%

summarise(n = n(), .groups = "drop_last") %>%

mutate(`%` = n / sum(n) * 100) %>%

mutate(`%` = `%` %>% round(1)) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")

```

And here we see the relative percent of different race groups within each BMI class.

```{r}

htwt %>%

group_by(bmiclass,

obsrace) %>%

summarise(n = n(), .groups = "drop_last") %>%

mutate(`%` = n / sum(n) * 100) %>%

mutate(`%` = `%` %>% round(1)) %>%

kable() %>%

kable_styling(full_width = FALSE, position = "left")

```

Even though the `n` values are the same in the two tables (e.g., underweight White n = `r htwt %>% filter(str_detect(obsrace, "White") & str_detect(bmiclass, "under")) %>% nrow()`), the percentages are different due to grouping. That is, the percent of underweight persons among the White race stratum is different from the percent of White persons within the underweight stratum. Proper grouping is critical to answer specific questions about the data.

Another way to understand the data, preferred by some, would be to make a graph. For example, BMI by race:

```{r}

bmi_race <- htwt %>%

group_by(obsrace,

bmiclass) %>%

summarise(n = n(), .groups = "drop_last") %>%

mutate(`%` = n / sum(n) * 100) %>%

filter(!str_detect(obsrace, regex("refused|know", ignore_case = TRUE)))

ggplot(data = bmi_race, mapping = aes(x = bmiclass, y = `%`)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, vjust = 0.5, hjust=1)) +

facet_grid(~obsrace)

ggplot(data = bmi_race, mapping = aes(x = obsrace, y = `%`, fill = bmiclass)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

coord_flip() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, vjust = 0.5, hjust=1))

```

## Source code

[07-week07.Rmd](07-week07.Rmd)

```{r comment=''}

cat(readLines(con = "07-week07.Rmd"), sep = '\n')

```