|

Complicated debates surround the precise origins of blues and jazz and the exact

mechanisms that turned them into the wellsprings of twentieth century American

(and world) popular music, but the basics are clear: southern musical styles

needed to come North to achieve commercial take-off. The Black Metropolises

became for musicians what they were for writers, settings that supported both

innovation and recognition.

The Mississippi River served as the chief highway of

the Jazz/Blues revolution. Black musicians had been traveling its length either

by boat or train in the late nineteenth century, some following the minstrel

show circuit, others the red light districts from New Orleans to Memphis, St.

Louis, and on to Chicago. Scott Joplin pushed Ragtime up the river in the late

1890s, performing and publishing his rags in St. Louis and Sedalia, Missouri,

Chicago and then New York where after the turn of the century the syncopated

beat found its way into countless tin pan alley compositions and vaudeville

shows, raising the tempo of American popular music.

Dixieland jazz followed during World War I....

The interactions were multiple and bi-directional. The Black Metropolises

drew the musically talented and musically curious from all over and from

various ethnicities. One of the interchanges was between black and white

musicians, some of them Jewish. The whites came to the blues and jazz clubs

in Harlem, on Chicago’s South Side, and on Central Avenue in Los Angeles to

listen and learn, taking many of the sounds they heard and turning them into

numbers that big crowds of young whites danced to in the ballrooms and clubs

across town. There was flattery in this theft and much more. The white jazz

bands paved the way for mainstream white audiences to begin to appreciate

new forms of music and the black artists who produced it. By the 1930s some

African American bandleaders would be working the big ballrooms and

appearing on the popular radio shows. The Swing era would also see the first

high visibility integrated bands, most notably the Benny Goodman orchestra.

White musicians got by far the better end of the bargain but these

interactions were changing not only the sounds but also the sociology of

American music.

Another interaction was regional. The northern city

entertainment zones were the principal hubs of an occupational migration

system that both drew musicians out of the South and moved them back through

it again. Like the attorneys, writers, and artists who knew they had to move

north to practice their professions, musicians were drawn to Chicago, New

York, Los Angeles, and other cities by the chance to make a career and

hopefully a living. The record companies, booking agents, and important

clubs were almost all in those cities and so was the excitement of hearing,

learning, and perhaps creating the hottest new music.

Southern cities had a role to play in this musical system.

Atlanta, Birmingham, New Orleans, Houston, Dallas, and Memphis each had

numerous and important jazz clubs and blues cellars. In the mid 1920s, after

race records had proved their market, the invention of portable electric

recording machines made it possible for the record companies to send teams

to these and other southern cities looking for new talent. But the southern

recording tours, which ended in 1931 when the Depression gutted the record

industry, did not alter the fundamental geography of musical opportunity.

The southern cities served as unofficial farm teams for the Black

Metropolises (just as they would in the system of Negro baseball that was

developing contemporaneously). Southern musicians got started on Atlanta's

Decatur Street or Memphis's Beale Street and the best of them then headed

for New York, Chicago, Kansas City, or Los Angeles hoping for a chance in

the majors. Alphabetically we can list a hundred names of blues and jazz

greats from Perry Anderson to Muddy Waters and all will tell the same story:

grew up in the South, honed their skills in the bordellos or clubs of a

southern city, went on to fame, if rarely fortune, in one of the music

capitals of the North or West.

excerpts from Ch

4 "The Black Metropolis"

|

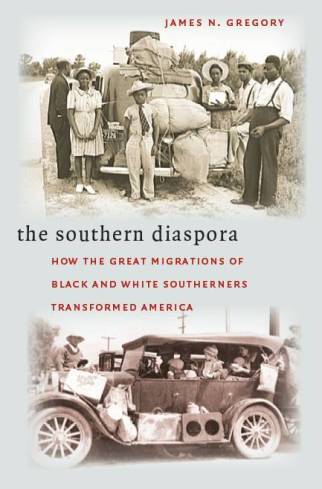

The

Southern Diaspora: How The Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners

Transformed America

is the first historical study of the Southern Diaspora in its entirety. Between

1900 and the 1970s, twenty million southerners migrated north and west. Weaving

together for the first time the histories of these black and white migrants,

James Gregory traces their paths and experiences in a comprehensive new study

that demonstrates how this regional diaspora reshaped America by "southernizing"

communities and transforming important cultural and political institutions.

Read

the catalogue description

and advance reviews.

Read the

Preface and Introduction.

|