|

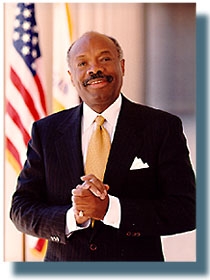

It started on the very first day that the freshman Assemblyman arrived in

Sacramento. Still exhilarated from his upset victory, Willie Brown was confident

that as the first African American from San Francisco elected to the legislature

he could make a difference. Always sure

of himself, he was perhaps less sure when it came to the rules of the California

Assembly. There was one critical rule that year, 1965, and it was simple:

Don’t mess with Big Daddy! Big Daddy was the 300-pound speaker of the

Assembly, Jesse Unruh. The press called him a "political boss" and

claimed he pulled more strings than the governor, Edmund G. "Pat"

Brown. In fact the governor and the speaker had mostly worked together. Over the

previous six years they passed a remarkable package of legislation that had

given the state strong civil rights laws, redesigned education, transportation,

and water systems, and financed ambitious urban and poverty programs. The

governor took most of the credit, Unruh through his ruthless control of the

legislature, had done much of the heavy lifting. He did not mind being

notorious, although he disliked the Big Daddy label, which had come from

Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. What he disliked even more were

legislators who did not know their place. He was not going to like Willie Brown.[i]

The Willie Brown-Jesse Unruh contest

is one of the best-loved stories of recent California politics. A feud that

turned ultimately into a succession story, it began on the first day of the 1965

session when Brown refused to support Unruh’s re-election to the speakership

because Unruh had campaigned for Brown’s primary election opponent. Even the

Republicans knew better than to hold out on Big Daddy. Unruh promptly

retaliated, and over the next several years the Assembly understood that the

very junior Brown and the very powerful Unruh were at war. Less obvious was the

fact that a kind of mentorship had been going on almost from the start. Willie

Brown was Jesse’s star student. Long before Big Daddy quit the legislature he

had come to admire the younger man’s ability to play the game of power. Unruh

at one point in 1967 offered a complement. “It’s a good thing you’re not

white,” said Jesse. “Why’s that?” asked Willie. “Because if you were,

you’d own the place.”[ii]

California journalists retell this

story both because it unites two of the state’s most flamboyant political

personalities and because it confirms one of the central fables of late

twentieth century America, the great transformation in racial opportunities that

has taken place since the 1960s. Willie Brown did go on to “own the place.”

Elected Speaker in 1981 with Unruh’s help, he served longer (15 years)

with more ingenuity than any predecessor, including Big Daddy. Without missing a

beat, Brown then moved up the political ladder, winning election as San

Francisco’s mayor in 1996 and holding on to that office through thick and thin

until term limits ended his reign in 2003.

The fact that Brown managed to out-do his mentor has served to make the

story of their relationship all the more interesting. In Willie and Jesse

California finds a comforting tale of racial progress, of the transformation

from an old California where only whites like Jesse Unruh held power, to a new

California that gives power to Willie Brown.

But the Jesse Unruh-Willie Brown

succession story has another dimension that few Californians realize and that in

some ways complicates the neat dichotomies of old and new, white and black.

Jesse Unruh was not part of old California, anymore than Willie Brown was. In

fact neither man was a Californian, neither had grown up there. And their

backgrounds were curiously similar. Both were southerners. In fact both were

Texans.

Unruh, whose parents named him after

the train robber Jesse James, was the son of

north- Texas sharecroppers. Brown grew up in east Texas in circumstances

that his biographer says may have been marginally more fortunate than Unruh’s.

Brown’s family had a long history in the all-black town of Mineola and owned a

nice home, even if money was short by the time he was born in 1934.

Willie was raised by his grandmother, aunts, and uncles while his mother

lived in Dallas where she worked as a maid. His father, a waiter, left when

Brown was four or five. Unruh was not born into poverty in 1922, but watched his

family descend into it, as his father lost his job as a bank clerk, then tried

sharecropping, managing to eke out only the barest of livings through much of

the 1930s. Both Texans benefited from family commitments to education and each

did well in school. After briefly trying college, Unruh in 1941, at age eighteen,

decided to hitchhike to Los Angeles thinking he would work in a defense plant.

When the war broke out, he enlisted in the Navy, spending the next three years

in the lonely Aleutian Islands, making plans for his future. Those plans were

fixed on Los Angeles and a college education. When the Navy let him go, he took

his GI bill and enrolled at the University of Southern California, finding there

his love for politics. Even before he graduated in 1948 he was planning a way

into politics. [iii]

Willie Brown was entering high school

that year, the segregated high school in Mineola. When he graduated three years

later, he briefly enrolled in one of the colleges that Texas set aside for

African Americans, Prairie View A&M near Houston. But another idea had been

brewing: he would go to Stanford. It was an impossible dream of course. There

was no money and Brown’s academic credentials would never pass muster at the

elite school, but an uncle lived in San Francisco and 17 year-old Willie Brown

figured that was pretty close. Stanford was on his mind in the summer of 1951

when he boarded the train heading west: “I came out with the intentions of

going to Stanford and becoming a math professor.”[iv]

That these two Texans should cross

paths in California in the mid 1960s was not particularly surprising.

For more than half a century, Texans and other southerners had been

leaving home by the hundreds of thousands, joining in a massive regional

diaspora that had changed the face of race and politics and other dimensions of

life in many corners of America. California felt the effects along with other

western states, but the diaspora had also delivered its millions to the

industrial states of the Midwest and Northeast. The numbers were enormous. By

the end of the 1960s so many black southerners and white southerners had left

the South that it was as if the entire population of Alabama, Mississippi,

Tennessee, and Arkansas had fled. Close to eleven million former southerners

could be counted living outside the South in 1970. And that number is just a

snapshot of population movements that over the course of the twentieth century

involved millions more, not all of whom left the South permanently. Altogether

more than 28 million southerners—black and white—participated in the

southern diaspora.[v]

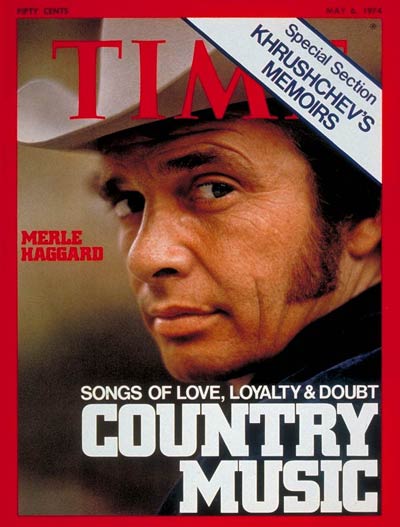

Aretha Franklin and Merle Haggard

should have crossed paths in the late 1960s. The two entertainers stood atop

their respective branches of popular music: she the reigning queen of soul, he

the king of country music. Like Brown and Unruh, they had more in common than

they would have realized. Both were children of the southern diaspora.

Franklin had grown up in Detroit after her family had moved there from

Tennessee, Haggard in Bakersfield, California after his parents relocated from

Oklahoma. Their music continued the symmetry. Aretha recorded "Respect”

in 1967, a song that instantly became a ringing anthem of black pride. Almost in

answer, Merle Haggard wrote "Workin' Man Blues" and "Okie from

Muskogee"--anthems of the angry and conservative white working class.

Seemingly politically opposite, the two musicians, both part of the diaspora,

symbolized some of the sharpest polarizations in American politics and culture

by the end of the 1960s.[vi]

This book is about Brown and Unruh, Franklin and Haggard, Graham and

another Franklin, Murray and Morris, and the millions of other diaspora

southerners and their impacts on twentieth century America. It is the first

historical study of the southern diaspora in its entirety. Historians have until

now fragmented the subject along lines of race and time period. The migration of

African Americans out of the South has been studied extensively, especially in

its early phase during and after World War I. Less has been written about the

more massive sequence of migration that began during World War II and a

comprehensive treatment of the century-long story of black migration does not

exist. Studies of white southerners on the move are more limited in number and

most focus on particular segments of that migration. Those who have written

about the movement of Appalachians and other southerners into northern cities

pay little attention to the so-called Dust Bowl migration to California and visa

versa. [ix]

This book assembles and disassembles the various sequences of southern

outmigration. African Americans and whites left the South for somewhat different

reasons, moved in somewhat separate directions, and interacted on very different

terms with the places they settled. In most respects we need to think in terms

of two Great Migrations out of the South. But they were also related. There were

similarities as well as differences in the motivations for leaving the South and

certain parallels along with huge differences in what black and white

southerners experienced and accomplished in the North and West.

One of the strategies of this book involves the side-by-side comparison

of the dual migrations. That stereoscopic view yields a host of new insights

about each of the groups and their experiences. The chapters that follow will

challenge many of the standard assumptions about the experiences of these former

southerners. The image of white Southerners struggling through decades of hard

living in "hillbilly ghettos" like Chicago's Uptown crumbles as we

widen the frame of reference. So do some of the stories that emphasize

disappointments and failures among blacks. Comparison of the community building

and political activities of the two groups is equally productive. The political

accomplishments of African Americans become all the more impressive when set

next to the endeavors of the much more numerous white migrants.

There is another reason for

integrating these stories. In complicated ways the fate of white and black

southerners outside their home region was often intertwined.

Especially that was the case in the two decades following World War II

when sociology and journalism created powerful arguments that linked the two

populations of former southerners. Moreover certain venues and projects drew

upon southern culture in ways that sometimes pulled the two groups of

expatriates into relationship. We see this in the postwar transformation of

northern Protestantism and the separate but in some ways complementary influence

of the evangelical churches that black migrants and white migrants built.

Likewise we see it in the transformation of American popular music—in the

country music that the white migrants helped spread as well as the multiple

genres that black migrants pioneered. And in the reconstructions of northern

politics-- the new forms of urban politics and racial liberalism that black

migrants forged, and the new forms of white-working-class conservatism that

white migrants helped shape. Even when their lives were separate, the two groups

of former southerners were never out of touch.

The book is not just about what the dual streams of former southerners

experienced. More centrally it examines what their comings and goings, their

struggles and creations, have meant for the United States over the course of the

twentieth century. The southern diaspora is one of the missing links in

historical understandings that recent century. As we will see, the great

migrations of black and white southerners were instrumental in many of the key

domestic transformations that the nation experienced, especially

reorganizations of race, religion, and region.

Some of the major stories of recent American history look very different

when viewed through the lens of the southern diaspora.

One story that looks different concerns black struggles for civil rights.

It is widely understood that migration to the North was important to the battle

for rights and respect, but the geography of black politics has rarely been

carefully examined. Here we pay close attention to the ways that African

American migrants were able to use the unique political capacities of the great

cities where they settled and how that political influence translated into

policy changes that transformed racial relations first in the North and West and

then also in the South.

The revival and spread of evangelical Protestantism (both black and white

versions), the southernization of American popular music through the

circulations of jazz, blues, hillbilly, and country music, new forms of black

politics and racial liberalism and new forms of white supremacist and

conservative politics were also part of the diaspora effect. Indeed key

political realignments of various kinds pivoted on the two groups of southerners

living outside their home region.

The reformulation of regions is another legacy of the dual diaspora.

Classical economists see migration as an equilibrium mechanism that over time is

supposed to balance labor surpluses and lead to a convergence of standards and

wages. This book pursues an argument that bears a superficial resemblance to

that theory but undermines its logic. Migration in this analysis contributed to

a convergence of many regional forms, not just economic but also political and

cultural. Southerners outside the South participated in a sequence of historical

transformations that changed the regions where they settled and also changed the

South, bringing the racial, religious, and political institutions of each into

closer relation. But no equilibrium theory can explain this convergence. These

changes prove to be the work of actual people not abstract economic processes.

Southern migrants of both races became agents of change, who used the

opportunities of geography to alter the cultural and political landscape of the

nation and all its regions.

Region is a fluid geographical concept

in the American context. States are the sub national spaces recognized in the

Constitution and equipped with clear boundaries and governmental institutions,

while regions are spaces of uncertain integrity and confusing borders. That is

true even of the South, long the most definite of American regions thanks to the

history of spatialized conflict over slavery and race. "If you look at the

whole South long enough," writes sociologist John Shelton Reed, "it

goes all indistinct around the edges. If you continue to stare, even the middle

can seem to melt and flow away." So scholars fight endlessly about how to

bound the South and describe its core meanings and structures. Those struggles

have their uses, but not to this study. We will define the South loosely and

even inconsistently, recognizing that definitions can change over time and

depend upon perspective. Is Florida a Southern state? Some would say yes at the

start of the twentieth century, no after decades of migration from New York and

Cuba. Are Baltimore and Washington D.C. southern cities? The argument here

involves not only change over time but racial perspectives. What makes a space

seem southern can differ for whites and blacks. For most purposes we will follow

the Census Bureau definition of sixteen states and the District of Columbia

(Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland,

Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas,

Virginia, West Virginia). But at other points we will reopen the issue of

boundaries. [x]

Race is another concept that requires

a note of clarification. White and black are never neat categories, even in a

place like the South that did so much to inscribe them in law and where until

late in the twentieth century low volumes of immigration minimized ethnic and

religious diversity within the two dominant racial groups. Although there will

be many generalized statements about white southerners and black southerners,

more nuanced discussions at certain points will remind us that these are

complicated population identities with mutable boundaries. In addition, it is

important to note that not all southerners acknowledge either racial label and

that southern-born Latinos and Native Americans also left the region during the

diaspora period. Their experiences will be distinguished briefly at some points

but unfortunately cannot be adequately examined in this study.

The book proceeds thematically rather than chronologically—the usual

strategy for a work of history. Each chapter is an essay that addresses a set of

particular questions using a stereoscopic method that moves back and forth

between the two groups of southerners. Stereoscopes set two similar but

different images next to each other, tricking eyes and brain into fusing the

images in a way that makes them three dimensional. Teasing out that third

dimension is the goal of this book. Viewed in relation to each other, the black

and white southern diasporas reveal the subject in entirely new ways.

Chapter 1 is an overview of the migration cycles and the changing

economics and demography over the course of the twentieth century. It offers a

new method for calculating migration volumes and shows the southern diaspora to

have been numerically larger than previous scholars have understood.

Chapter 2

surveys the public meanings surrounding the two exoduses and highlights the

unique role that media institutions and social scientists played in shaping the

expectations and interactions of southerners on the move.

Chapter 3 answers

questions about the economic experience of white and black southerners,

dismantling the maladjustment paradigm that has been so prominent in previous

scholarship while also showing the critical differences in the opportunity

structure facing black and white southern migrants.

Chapter 4 examines the

communities that African Americans built in the major cities, resurrecting the

label “Black Metropolis,” and mapping the new and powerful cultural

apparatus of those communities.

Chapter 5 examines the very different community

formations of white southerners who spread out through suburbs and rural areas

as well as big cities and struggled with confusing issues of social identity.

The whites, too, developed cultural institutions of historical import. Both

diaspora country music and a white diaspora literary community would reshape

understandings of region and race.

Chapter 6 explores the diaspora’s impact on

American religion as both groups built Baptist and Pentecostal churches and

helped revitalize and spread evangelical Protestantism, with important political

as well as religious implications for America.

Chapter 7 develops the issue of

black political influence, demonstrating how important geography was to the

initial phases of what ultimately becomes the civil rights movement.

Chapter 8

brings the white migrants into the story of race, class, and regional

transformations, exploring contributions on the one hand to white-working class

conservatism and on the other hand to new formulations of white liberalism.

Chapter 9 brings the diaspora to a close in the 1970s and 1980s and summarizes

some of the major findings of the book.

A short invocation before we begin. This book in its largest sense is a

call for new thinking about internal migration, one of the seriously under

analyzed issues of twentieth century American historiography. While the

scholarship of earlier centuries focuses imaginatively on the figure of the

Moving American and treats the westward migration of Euro-Americans as a pivotal

historical force, historians of the most recent century sideline the subject of

internal migration. Migration is treated as an important matter for African

American history, but other population movements rarely enter into the

calculations of those writing the history of the American twentieth century.[xi]

If historians have failed to adequately address the subject, social

scientists have not done much better. Migration studies, once a cutting edge

enterprise for sociologists and economists, have been stuck for decades in dead

ends and stale formulations. Most of the work cannot get beyond the question of

why migrations happen, the old push-pull conundrum. Huge debates rage between

advocates of neoclassical economic theory and dependency theory, both of which

contemplate migration as a response to differential economic development. A

third formulation, migration systems theory (a version of which is sometimes

called exodus theory), moves beyond economic conditions, treating migration as a

social movement and specifying institutional and social-cultural factors that

enable mass relocations, but it too concentrates solely on the causes of

migrations while ignoring their effects. All of these perspectives see moving

people as subject to history but not its architects.[xii]

An old theory, dating back to the

late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, holds some promise. It conceives

migration is a fundamental force of history. The social scientists who crafted

it had in mind conquest migrations of the sort that rearranged European and

Asian empires in millennia past, or that transformed the Americas when Europeans

came swarming across the Atlantic. But

conquest may not be the only basis through which moving masses can redirect the

flow of history. Infiltration can also be powerful. Certain peoples moving into

certain places have managed to impart dramatic changes, achieving conquests of a

sort without warfare and sometimes without major conflict. Can internal

migrations have consequences of this sort? If so, how? Those are the questions

animating this book. [xiii]

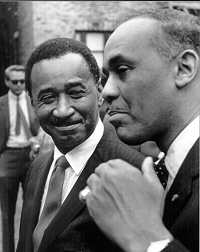

Billy Graham and C.L. Franklin should also have met. Fellow Baptists,

fellow evangelists, fellow southerners who had built great religious enterprises

in the North, they understood that they had much in common. As ministers of the

gospel they shared a mission. They would have prayed for their nation to heal

its divisions and come together in a spiritual revival that would sweep away the

hatreds of race. But even as their prayers might have joined, the meanings

behind them would have been different. Graham, the most famous white Protestant

leader of his day, a son of North Carolina who from his base in Minnesota had

changed the face of evangelical Christianity, making it respectable where it had

once seemed backward, preached a Christianity that was nine parts personal

salvation. Franklin, a son of Mississippi (and

father of Aretha), had been for many years one of the nation's most famous black

evangelists. His sermons, recorded at New Bethel Church in Detroit, were known

and loved throughout black America. But unlike Graham's, Franklin’s preaching

was not just about personal salvation. He also called for African Americans to

stand together in the fight for rights and justice.[vii]

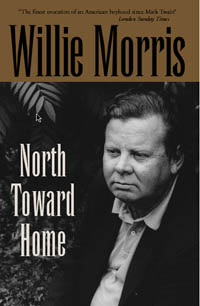

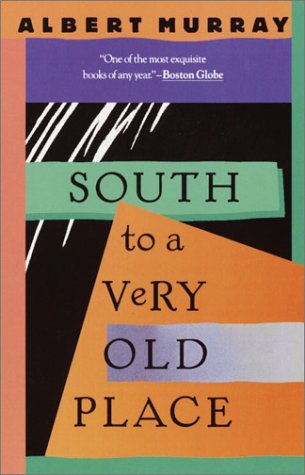

Unlike these other pairs, Albert Murray and Willie Morris did know each

other. Indeed the black writer and the white writer had spent New Years day 1967

together in Murray's Harlem apartment, drinking bourbon, talking politics, and

thinking about their parallel and unparallel lives. Morris, the 32-year old

editor of Harper's Magazine was just then completing a memoir, North

Toward Home, filled with critical memories of Mississippi and of the

conflicts that rattled the faith of a liberal white southerner living in New

York City. He wanted Murray to write something for the magazine about his own

life's journey from rural Alabama to literary Harlem. Murray would eventually

take the assignment and turn it into memoir whose syncopated rhythms and

perambulating conversations had little in common with North Toward Home.

But the title, South to a Very Old Place, suggested something of the

linked origins of the two books and the intertwined lives of their authors.[viii]

|

Willie

Brown and Jesse Unruh.

Brown

helps Unruh count the votes as Jesse is re-elected Speaker of the

California Assembly in 1968 (Sacramento Bee photo courtesy City of

Sacramento Archives and Museum Collection Center)

Aretha

Franklin was the "Queen of Soul" when she appeared on the cover

of Time May 28, 1968

Merle Haggard

on the cover of Time May 6, 1974

Above: C.L Franklin in the

1960s. Below: Billy Graham on a Detroit

visit in 1952 (Courtesy Walter Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

Albert Murray and

Ralph Ellison

Willie Morris

|