| Dyslexia |  |

| Dyslexia |  |

What is Dyslexia?Dyslexia is a disorder that is characterized by a difficulty processing words. Reading problems are one symptom of dyslexia. "Dys" means bad or difficult and "lexia" means word. The problem was first described in 1896 by Dr. W. Pringle Morgan in England. He wrote of a "bright and intelligent boy quick at games and in no way inferior to others of his age. His great difficulty has been - and is now - his inability to learn to read."Dyslexia can occur in several members of a family. This suggests that there is a genetic component to the disorder. Dyslexia also varies in degree of severity, thus affecting some people much more than others.

|

Frustrating Phonemes It is now known that the brains of dyslexics are "wired" differently than

normal brains, and thus process language less efficiently. In particular,

dyslexics have trouble with the units of language called phonemes. Phonemes are defined as the smallest units of

sound used for language. For example, the spoken word "cat"

is made up of three phonemes: kuh, aah, tuh. There are 44 phonemes in the

English language. For most people, the process of breaking words into

phonemes occurs automatically, without conscious thought. Just as we

break down phonemes without thinking about it, we also merge them in our

speech automatically: "cat" is one syllable, but made up of three distinct

sounds. Between the ages of 4 to 6, most children are aware that phonemes

make up words.

It is now known that the brains of dyslexics are "wired" differently than

normal brains, and thus process language less efficiently. In particular,

dyslexics have trouble with the units of language called phonemes. Phonemes are defined as the smallest units of

sound used for language. For example, the spoken word "cat"

is made up of three phonemes: kuh, aah, tuh. There are 44 phonemes in the

English language. For most people, the process of breaking words into

phonemes occurs automatically, without conscious thought. Just as we

break down phonemes without thinking about it, we also merge them in our

speech automatically: "cat" is one syllable, but made up of three distinct

sounds. Between the ages of 4 to 6, most children are aware that phonemes

make up words.

Trouble with PhonemesBecause dyslexics cannot decode words, they have trouble accessing the information they have stored pertaining to that word. They often confuse like-sounding words, such as "volcano" and "tornado." When shown a picture of a volcano, for example, a dyslexic might call it a "tornado," yet when asked to define what it does will correctly answer that it can erupt and spew hot lava. In other words, the dyslexic knows what the object is, but he or she cannot access the correct word for it.

|

"Compensated" DyslexicsThere is a term for dyslexics who find ways to overcome their learning disability: compensated dyslexics. A person with dyslexia can be very successful; dyslexia does not affect one's intelligence. Dyslexics often excel at problem solving, critical thinking, and vocabulary. They are usually adept at grasping "the big picture" of a concept. Dyslexics often excel at architecture, engineering, science, art and music.

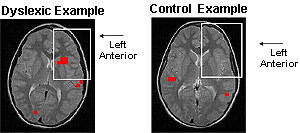

Dyslexic Brains "Look" DifferentDr. Sally Shaywitz, a researcher at the Yale University of Medicine showed in 1998 that areas in the back of the brain that are usually activated when readers sounded out words are significantly less activated in dyslexics' brains. Moreover, areas in the front of the brain displayed more activity in dyslexics' brains than in the brains of normal readers. More recently, researchers at the University of Washington have shown that dyslexics' brains work up to five times harder than non-dyslexic brains. Girard Sagmiller, in his website called What is Dyslexia?, describes dyslexia "like running a 100-meter race. In your lane you have hurdles, but no one else does. You feel that it's unfair but you try running like the other competitors anyway."

|  These photographs are used with the permission of Dr. Todd Richards, University of Washington. |

What Can Be Done According to Dr. Shaywitz, most children are not diagnosed with dyslexia

until the third grade. If a diagnosis could be made earlier, students

could be given extra help before they start to have difficulties in their

schoolwork. This may mean that parents need to work with the school to

make sure their child receives the help needed. Federal legislation in

place since 1975 requires that special funding be available to provide

learning disabled children equal opportunities in the educational

system.

According to Dr. Shaywitz, most children are not diagnosed with dyslexia

until the third grade. If a diagnosis could be made earlier, students

could be given extra help before they start to have difficulties in their

schoolwork. This may mean that parents need to work with the school to

make sure their child receives the help needed. Federal legislation in

place since 1975 requires that special funding be available to provide

learning disabled children equal opportunities in the educational

system.Research indicates that early training in phoneme awareness helps dyslexics read better. This specific type of language training focuses on the sound structure of words, not simply on overall reading skills. There are now software programs available that slow down or stretch out the sounds of words, helping children practice breaking words into phonemes. Dyslexics may also have trouble with long or novel words. It is difficult for dyslexics to master rote memorization, as they need contextual clues to help them gain the meaning of words. Therefore, multiple choice exams are more challenging for dyslexics, and many schools offer other test formats for dyslexics, ones that fairly test knowledge while providing context for the questions and answers, such as essays or oral exams. Dyslexics often say they feel tired because reading takes them longer than non-dyslexics. Many schools provide extended test times for dyslexics to allow for a fair assessment of what has been learned.

|

Quick Facts

|

|

References:

Organizations/Support Groups:

|

![[email]](./gif/menue.gif) Send E-mail |

![[newsletter]](./gif/menunew.gif) Get Newsletter | ![[search]](./gif/menusea.gif) Search Pages |

By Ellen Kuwana

Neuroscience for Kids Staff Writer