| Unraveling Dyslexic Brains |  |

| Unraveling Dyslexic Brains |  |

| By Ellen Kuwana Neuroscience for Kids Staff Writer December 10, 1999

What is Dyslexia?You may have heard of dyslexia. You may even know someone who has been diagnosed with dyslexia. Some people joke that they are "dyslexic" because once in a while they mix up words, such as confusing "brain" with "brian." But to those who have dyslexia, it is not a joking matter. Dyslexia is a frustrating disorder. It's much more than getting certain words confused with other words - it's having trouble processing words. |

Literally Looking at Dyslexic BrainsResearchers at the University of Washington in Seattle are making strides understanding how dyslexic brains work. Developmental neuropsychologist Virginia Berninger, Ph.D., and neurophysicist Todd Richards, Ph.D., lead a team of researchers whose studies have shown that the brains of children with dyslexia work about five times harder than other children's brains when performing the same language task. You think you're tired at the end of a school day? Imagine if your brain had to work five times harder!Berninger and Richards have recently published the first study showing that there are chemical differences between the brains of children with dyslexia and those of other children. These researchers used a technique called PEPSI (proton echo-planar spectroscopic imaging) which shows the metabolic activity of the brain. When the brain is at work, it uses energy (just like you need food for energy before you go for a hike). One by-product of energy use in the brain is lactate. By measuring where lactate is being produced, the scientists were able to see which part of the brain was active. This is a non-invasive technique, meaning that they did not have to use instruments or procedures that go inside the body. It was very safe and painless. |  Child getting ready for a functional MR

spectroscopic |

The Test SubjectsThe researchers looked at six boys with dyslexia and seven non-dyslexic boys. The boys were all between the ages of eight and 13. The boys with dyslexia had a family history of dyslexia and were reading below their age level. The non-dyslexics were all reading above their age levels.

The TestsThe boys all wore headphones and listened to pairs of words. The word pairs consisted of:

|

The Test Results - Dyslexic Brains Work Harder | |

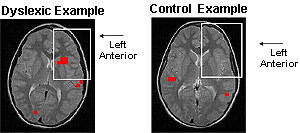

| The boys needed to identify whether the words rhymed or not, and whether the words were real words or nonsense words. It was during this language test that the dyslexic brains worked harder (as measured by increased lactate levels). The main area that was activated was the left frontal lobe (see figure on the right). It is unclear whether the brain is working harder because it is working less efficiently or because additional pathways are being activated in the brain as a way to compensate. These results in children parallel results from similar studies with adult dyslexics. |  These photographs are used with the permission of Dr. Todd Richards, University of Washington. |

The researchers also observed whether the brain was

activated during any

tasks that require listening and thinking involving musical tones. Each

boy heard two tones, and was asked to decide if they were the same notes

or two different notes. In this task, the dyslexic and non-dyslexic brains

worked the same way. So the difference was specific to making sense of

language, not just auditory input.

tasks that require listening and thinking involving musical tones. Each

boy heard two tones, and was asked to decide if they were the same notes

or two different notes. In this task, the dyslexic and non-dyslexic brains

worked the same way. So the difference was specific to making sense of

language, not just auditory input.Dyslexia is a common reading disorder that affects 5-15% of school-aged children. It is a lifelong disorder that can be treated but not cured. Dyslexics can learn to compensate for their weaknesses in language. They can be successful people with tremendous talent: Albert Einstein, Thomas Edison and humorist Erma Bombeck were dyslexic and actor Tom Cruise has dyslexia. They had to work harder to learn to read and spell, but obviously, they were still able to excel. | |

|

References:

|

| BACK TO: | Neuroscience In The News | Table of Contents |

![[email]](./gif/menue.gif) Send E-mail |

![[newsletter]](./gif/menunew.gif) Get Newsletter | ![[search]](./gif/menusea.gif) Search Pages |