Information technology

My family’s first computer was an Apple IIe computer. We bought it in 1988 when I was 8. My mother had ordered it after $3,000 saving for two years, hearing that it could be useful for word processing, but also education. It arrived one day in a massive cardboard box and had to be assembled. Before my parents got home, I had opened the box and found the assembly instructions. I was so curious about the strange machine, I struggled my way through the instructions for two hours, I had plugged in the right cables, learned about the boot loader floppy disk, inserted into the floppy disc reader, and flipped the power switch. The screen slowly brightened, revealing its piercing green monochrome and a mysterious command line prompt.

After a year of playing with the machine, my life had transformed. My play time had shifted from running outside with my brother and friends with squirt guns to playing cryptic math puzzle games, listening to a homebody mow his lawn in a Sims-like simulation game, and drawing pictures with typography in the word processor, and waiting patiently for them to print in the dot matrix printer. This was a device that seemed to be able to do anything, and yet it could do so little. Meanwhile, the many other interests I had life faded, and my parents’ job shifted from trying to get us to come inside for dinner to trying to get us to go outside to play.

For many people since the 1980’s, life with computers has felt much the same, and it rapidly led us to equate computers with technology, and technology with computers. But as I learned later, technology has meant many things in history, and quite often, it has meant information technology.

What is technology?

The word technology comes from ancient Greece, combining tekhne , which means art or craft , with logia , which means a “subject of interest” to make the word tecknologia . Since ancient Greece, the word technology has generally referred to any application of knowledge, scientific or otherwise, for practical purposes, with its use evolving to refer to whatever recent inventions had captivated humanity 5 5 Stephen J. Kline (1985). What is technology?. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society.

| 15000 BC | stone tools |

|---|---|

| 2700 BC | abacus |

| 900’s | gunpowder |

| 1100’s | rockets |

| 1400’s | printing press |

| 1730’s | yarn spinners |

| 1820’s | motors |

| 1910’s | flight |

| 1920’s | television |

| 1930’s | flying |

| 1950’s | space travel |

| 1960’s | lasers |

| 1970’s | computers |

| 1980’s | cell phones |

| 1990’s | internet |

| 2000’s | smartphones |

While many technologies are not explicitly for the purpose of transmitting information, you can see from the ones in bold in the table above that most technology innovations in the last five hundred years have been information technologies 4 4 James Gleick (2011). The information: A history, a theory, a flood. Vintage Books.

A second thing that is clear from the history above is that most technologies, and even most information technologies, have been analog, not digital, from the abacus for calculating quantities with wooden beads almost 3,000 years ago to the smartphones that dominate our lives today. Only since the invention of the digital computer in the 1950’s, and their broad adoption in the 1990’s and 2000’s, did the public start using the word “technology” to refer to computing technology.

Early information technologies

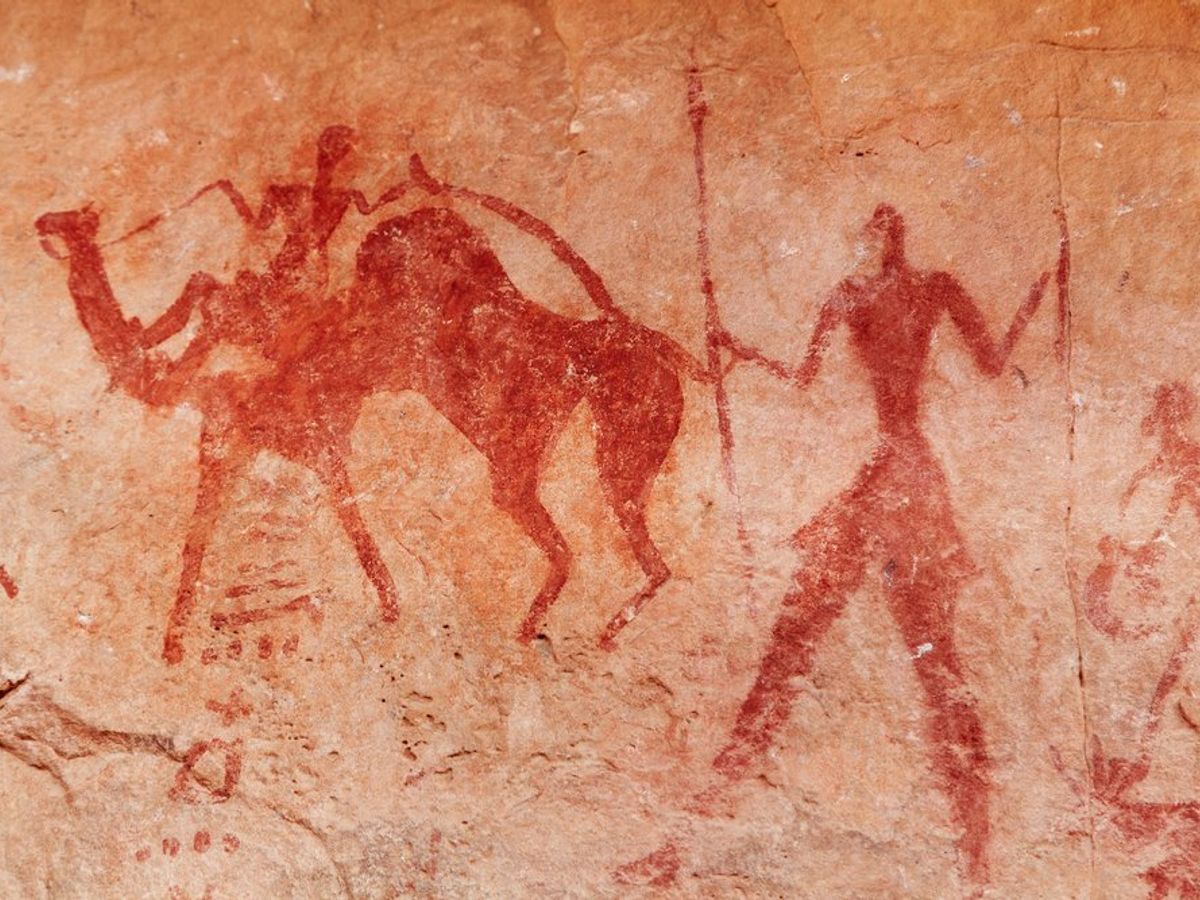

The history of information technologies, unsurprisingly, follows the evolution of humanity’s desire to communicate. For example, some of the first information technologies were materials used to create art , such as paint, ink, graphite, lead, wax, crayon, and other pigmentation technologies, as well as technologies for sculpting and carving. Art was one of humanity’s first ways of communicating and archiving stories 6 6 Shigeru Miyagawa, Cora Lesure, Vitor A. Nóbrega (2018). Cross-modality information transfer: a hypothesis about the relationship among prehistoric cave paintings, symbolic thinking, and the emergence of language. Frontiers in Psychology.

Spoken language came next 9 9 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John H. Moran, Johann Gottfried Herder, Alexander Gode (2012). On the Origin of Language. University of Chicago Press.

Writing came later. Many scholars dispute the exact origins of writing, but our best evidence suggests that the Egyptians and Mesopotamian’s, possibly independently, created the early systems of abstract pictograms to represent particular nouns, as well as early Chinese civilizations, where symbols have been found on tortoise shells. These early pictographic scripts evolved into alphabets and character sets, and exploited any number of media, including walls of caves, stone tablets, wooden tablets, and eventually paper. Paints, inks, and other technologies emerged, eventually being refined to the point where we take immaculate paper and writing instruments such as pencil and pens for granted. Some found writing dangerous; Socrates, the Greek philosopher, for example, believed that the written word would prevent people from harnessing their minds:

For this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise.

Plato (-370). Phaesrus. Cambridge University Press.

Writing, of course, was slow. Even once humanity had created books, there was no way to copy them other than painstakingly transcribing every word onto new paper. This limited books to the wealthiest and most elite people in society, and ensured that news was only accessible via word of mouth, reinforcing systems of power undergirded by access to information.

The printing press , invented by goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg around 1440 in Germany, solved this problem. It brought together a box full of letter blocks on which ink could be applied, another box in which letters were placed, and a machine, which would lay ink upon the lead blocks, and then paper would be rolled to apply the ink. With this mechanism, copying a text went from taking months to minutes, introducing the era of mass communication, permanently transforming society through the advent of reading literacy. Suddenly, the ability to access books and newspapers , and learn to read them, lead to a rising cultural self-awareness through the circulation of ideas that prior had only been accessible to those with access to education and books. To an extent, the printing press democratized knowledge—but only if one had access to literacy, likely through school.

While print transformed the world, in the late 18th century, the telegraph began connecting it. Based on earlier ideas of flag semaphores in China, the electrical telegraphs of the 19th century connected towns by wires, encoding what were essentially text messages via electrical pulses. Because electricity could travel at the speed of light, it was no longer necessary to ride a horse to the next town over, or send a letter via train. The telegraph made it possible to send a message without ever leaving your town.

Around the same time, French inventor Nicéphore Niépce invented the photograph , using chemical processes to expose a film to light over the course of several days, allowing for the replication of images of the world. This early process led to more advanced ones, and eventually black and white film photography in the late 19th century, and color in the 1930’s. It was much longer after the first photographs that the first motion pictures were invented. Photography and movies became, and continues to be, the dominant way that people capture moments in history, their own, and the world’s.

While photography was being refined, in 1876 Alexander Graham Bell was granted a patent for the telephone , a device much like the telegraph, but rather than encoding text through electrical pulses, it encoded voice. The first phones were connected directly to each other, but later phones were connected via switchboards, which were eventually automated by computers, creating a worldwide public telephone network.

During nearly the same year in 1887, Thomas Edison and his crew of innovators invented the phonograph , a device for recording and reproducing sound. For the first time, it was possible to capture live music or conversation, store it on a circular disk, and then spin that disk to generate sound. It became an increasingly popular invention, and lead to the recorded music industry.

Shortly after, at the turn of the century, broadcast radio emerged from the innovations in recording sound, and both homes and workplaces began to use radios to receive information across AM and then FM bands. Shortly after that, combining radio with motion picture technology, the first live transmission of television occurred in Paris in 1909, and just a decade later, televisions began entering the homes of millions of people.

While this brief history of information technology overlooks so many fascinating stories about science, engineering, and innovation, it also overlooks the fascinating interplay between culture and information technology. Imagine, for example, living in the era prior to books and literacy, and then suddenly having access to these mythical objects that contained all of the ideas of the world. Books must have created centuries of wonder on the part of people who may have never left their small agricultural community. Or, imagine living at the beginning of the 20th century, where books were taken for granted, but photographs, movies, telephones, radio, and television connected the world in ways never before possible, centering broadcast information technology for the next 80 years as the dominant form of communication. Thus, much as we are fascinated by computers and the internet now, people were fascinated by television, books, and the telegraph before it.

Computing emerges

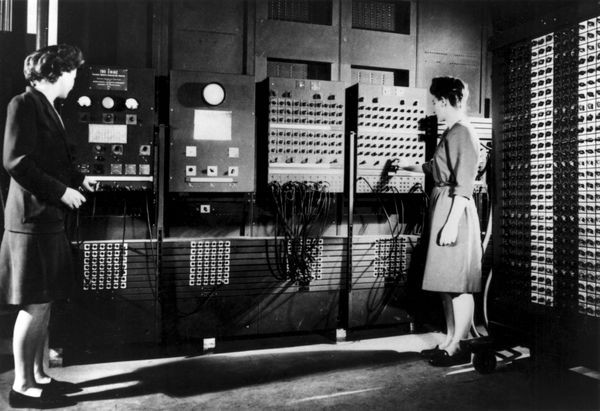

It took tens of thousands of years for humanity to invent writing, millennia to invent the printing press, a few hundred years to invent recorded and broadcast media, and just fifty years to invent the computer. Of course, this is a simplification: Charles Babbage , a mathematician and inventor who lived in 19th century England first imagined the computer, describing a mechanical device he called the difference engine that could take the numbers as inputs, and automatically compute arithmetic operations on them. His dream was to replace the human computers of the time, who slowly and painstakingly and sometimes incorrectly calculated mathematical formulas for pay. His dream mirrored the broader trends of industrialization and automation at the time, when people’s role in industry shifted from making with their hands to maintaining and supporting machinery that would do the making. This vision capitivated his protogé, Ada Lovelace , the daughter of a wealthy poet Lord Byron. She wrote extensively about the concept of algorithms and how they might be used to compute with Babbage’s difference engine.

In the 1940’s, Alan Turing was examining the theoretical limits of computing, John Von Neumann was laying the foundations of digital computer architecture, and Claude Shannon was framing the theoretical properties of information. All of these men were building upon the original visions of Babbage, but thinking about computing and and information in strictly mathematical and computational terms. However, at the same time, Vannevar Bush , the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development in the United States, had an entirely different vision for what computing might be. In his landmark article, As We May Think 1 1 Vannevar Bush (1945). As we may think. The atlantic monthly.

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory... Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified. The lawyer has at his touch the associated opinions and decisions of his whole experience, and of the experience of friends and authorities. The patent attorney has on call the millions of issued patents, with familiar trails to every point of his client’s interest. The physician, puzzled by a patient’s reactions, strikes the trail established in studying an earlier similar case, and runs rapidly through analogous case histories, with side references to the classics for the pertinent anatomy and histology. The chemist, struggling with the synthesis of an organic compound, has all the chemical literature before him in his laboratory, with trails following the analogies of compounds, and side trails to their physical and chemical behavior.

Vannevar Bush (1945). As we may think. The atlantic monthly.

If this sounds familiar, it’s no coincidence: this vision inspired many later inventors to realize this vision, including Douglas Engelbart , who gave a demonstration of the NLS , a system resembling Bush’s vision, which inspired Xerox Parc to explore user interfaces with the Alto , which inspired Steve Jobs to create the Apple Macintosh , which set the foundation for the future of personal computing we have today.

(If you’re wondering why all of these inventors were White men, look no further than the 20th century universities in the United States and United Kingdom, which systematically excluded women and people of color until the 1960’s. Universities are where most of this invention occurred, and where all of the world’s computers were, as computers took up entire rooms rooms in which women, Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Native people simply weren’t allowed).

The underlying ideas of computing followed a very simple architecture, as depicted in the video above:

- Computers encode programs as a series of numbered instructions.

- Instructions include things like add , multiply , compare , and jump to instruction

- Instructions can read data from memory, and store data in memory

- Computers execute programs by following each instruction until the program halts.

- Computers can take inputs from users and give outputs to users.

In essence, computing is nothing more than the ideas above. The magic of computing, therefore, emerges not from these simple set of rules that govern computer behavior, but how the instructions in computer programs are assembled to do magical things. In fact, part of Turing’s theoretical contribution was observing that the ideas above have limits: it is not possible to write a program to calculate anything we want, or do anything we want. In fact, some programs will never finish computing, and we will not be able to know if they ever will. Those limits are fundamental and inescapable, as certain as any mathematical proof.

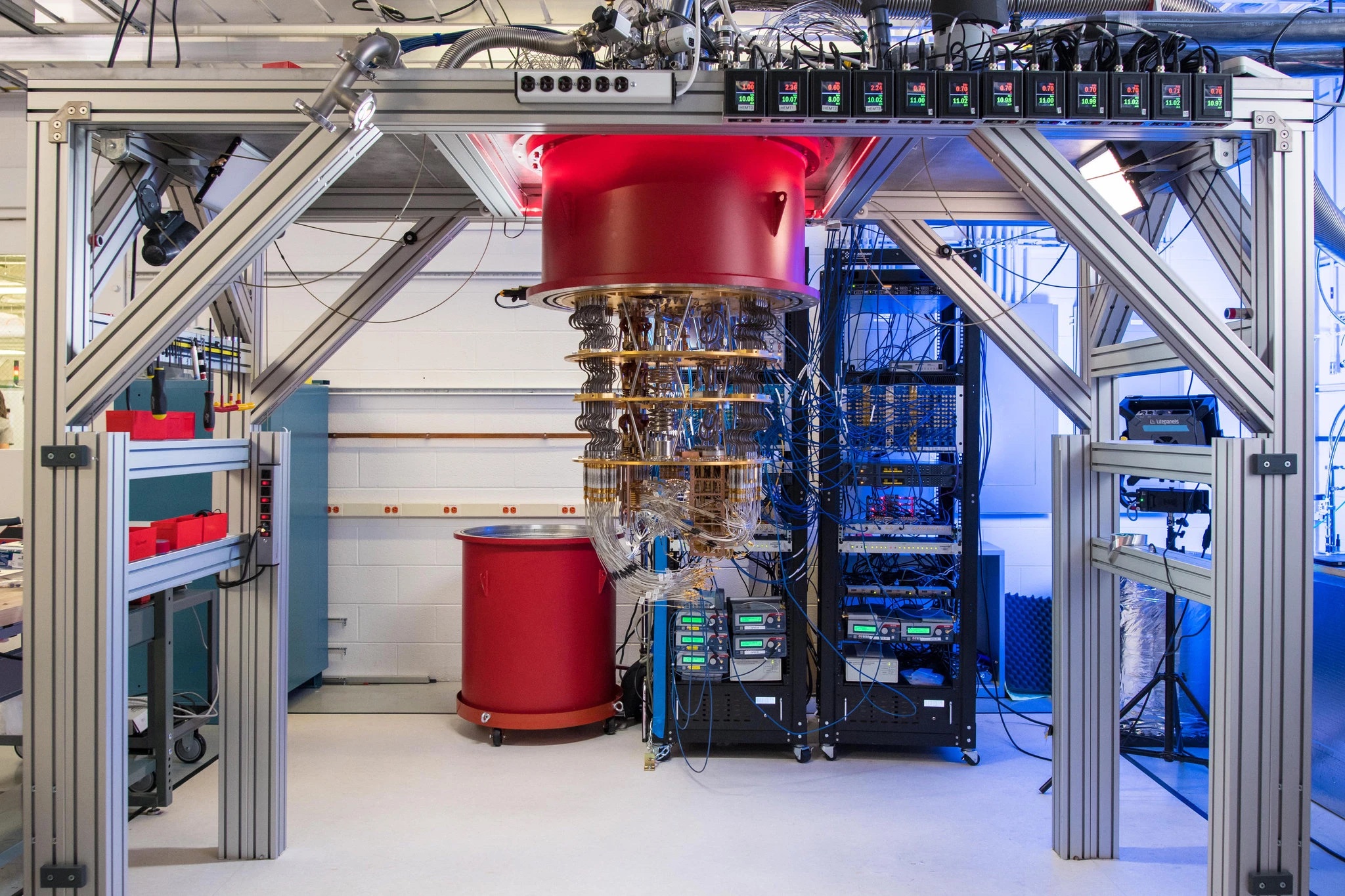

Yet, as an information technology, if we program them to, computers can do a lot. They can take in data, store it, analyze it, manipulate it, even capture it, and then retrieve and display it. This is far more any of the information technologies in the history we discussed earlier, and it could do it far faster and more reliably than any prior technology. It is not surprising then that since the 1950’s, computers have transformed all of the prior technologies, replacing the telephone with Voice Over IP, the film photograph with digital photographs, analog music with digital, and print documents with digital documents. The computer has not really contributed new ideas about what information technology can be, but rather digitized old ideas about information technology, helping us to make them easier to capture, process, and retrieve.

Is computing the superior information technology?

There are many things that make computers an amazing form of information technology. They can store, process, and retrieve data faster than anything we have ever invented. Through the internet, they can give us more data than we could ever consume, and connect us with more people than we could possibly ever know. They have quickly exceeded our needs and wants, and as we continue to invest in enabling them to do more powerful things, we will likely continue to.

But are computers really the best information technology? Just because they are the most recent, doesn’t necessarily mean they are superior. Let us consider a few of their downsides relative to older information technologies.

- Amplification . Because computers are so fast and spread data so easily, they have a tendency to amplify social trends far more than any prior information technology 10 10

Kentaro Toyama (2015). Geek heresy: Rescuing social change from the cult of technology. PublicAffairs.

, for better or worse. In the case of spreading information about a cure to a deadly virus, this amplification can be a wonderful thing, saving lives. But amplification can also be negative, helping disinformation spread more rapidly than ever before. Is this a worthwhile tradeoff? For the victims of amplification, such as those oppressed by hate speech, harassment, or even hate crimes spurred by division in online communication, the answer is a clear no. - Automation . In prior forms of information technology, there are many different people involved in making information move. For example, prior to automated telephone switching, it was possible to talk to human telephone operators if you had a wrong number; they might know who you were trying to reach, and connect you. With code, however, there is no person in the loop, no person to question the logic of code. Is it better to have slowly executed instructions that you can interrogate, question, and change, or quickly executed instructions that you cannot challenge? If you are marginalized in some way in society, with no way to question the automation and its decisions 2 2

Virginia Eubanks (2018). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. St. Martin's Press.

, then the answer is once again no. - Centralization . At the height of news journalism, there were tens of thousands of news organizations, each with their own values, focus, and ethics. This diversity built a powerful resilience to misinformation, leading to competition for investigation and truth. With computers and the internet, however, there are fewer distributors of information than ever: Google is the front door to most of of the data we access, Amazon the front door of the products we buy, and Facebook (and its other social media properties) is the front door of the people we connect with. If we don’t find the information we need there, we’re not likely to find it elsewhere, and if we don’t like how those services work, we have fewer alternatives than ever. Is the benefit that comes from centralization worth lost choice and agency? If the services above have effectively erased your business from the internet, eliminated your sales, or led to the spread of misinformation that harms you and your community 7 7

Safiya Noble (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

, once again, no.

The dominant narrative that positions computing as superior rests upon the belief that all of the trends above are ultimately better for society. But the reality is that computing is not magic, computing is not infinitely powerful, computing is highly dependent on human labor to write code and create data, and most of the reason that people want computers is because they want information. As we have seen throughout history, fascination with the latest form of information technologies often grants far too much power to the technology itself, overlooking the people behind it and how it is used.

Of course, computing is far more powerful than any information technology we have invented. Many argue that it is leading to a fundamental shift in human reality, forcing us to accept that both natural and virtual realities are real and posing new questions about ethics, values, and society 3 3 Luciano Floridi (2014). The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality. OUP Oxford.

Podcasts

Learn more about information technology:

- The AI of the Beholder, In Machines We Trust, MIT Technology Review . Discusses recent advances in applying machine learning to beauty, and the shift from altering our physical appearance with makeup and surgery to altering the pixels that represent it. Discusses racism, ageism, and other biases encoded into beautification algorithms.

- A Vast Web of Vengeance, Part 2, The Daily, NY Times . Discusses the maintainers of websites who spread information that harms reputations, how Section 230 protects them, and the extortion that some companies use to have defamatory information removed.

- The Most Thorough case Against Crypto I’ve Heard, The Ezra Klein Show, NY Times . Discusses the numerous risks of decentralized currency, intersecting with issues of privacy, property, and individualism.

References

-

Vannevar Bush (1945). As we may think. The atlantic monthly.

-

Virginia Eubanks (2018). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. St. Martin's Press.

-

Luciano Floridi (2014). The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality. OUP Oxford.

-

James Gleick (2011). The information: A history, a theory, a flood. Vintage Books.

-

Stephen J. Kline (1985). What is technology?. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society.

-

Shigeru Miyagawa, Cora Lesure, Vitor A. Nóbrega (2018). Cross-modality information transfer: a hypothesis about the relationship among prehistoric cave paintings, symbolic thinking, and the emergence of language. Frontiers in Psychology.

-

Safiya Noble (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

-

Plato (-370). Phaesrus. Cambridge University Press.

-

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John H. Moran, Johann Gottfried Herder, Alexander Gode (2012). On the Origin of Language. University of Chicago Press.

-

Kentaro Toyama (2015). Geek heresy: Rescuing social change from the cult of technology. PublicAffairs.