Information systems

When I started middle school at the age of 12, I had the great fortune of being the first class in a brand new building. The architecture was a beautiful half circle, and large attached box on the side. The box housed a large gym and our cafeteria. The two levels of the half circle contained several dozen classrooms and lockers. And in the center of the half circle, below a radiant glass ceiling in a fully open atrium, was our library, rich with short stacks of books, desks of computers, and several rows of seating. This library was clearly meant to be the heart of the school, representing knowledge and discovery, and the hub connecting the classrooms, the gym, the cafeteria, and the outside world. Every week, throughout middle school, we had a library class, where we learned how to use a card catalog, how to read carefully, how to write a bibliography, and about the wonderful diversity of the genres, from young adult pulp fiction to historical non-fiction. Our librarian loved books and loved teaching us to love them.

At home, I encountered a different world of knowledge. My family had a new PC, and inside it was something called a modem, which we plugged into our phone line, and used to connect to the internet via a service called America Online (AOL). When we wanted to connect, we made sure no one needed to use the phone, then initiated a connection to AOL. The modem’s speaker would make a phone call to AOL, but instead of voice, it made a piercing screech. After a minute, we would hear the affirming sound of a connection, when we knew we were online. Once there, I had a similar sense as I did at my school library, that I was connecting with the world. But this world, rather than being full of carefully written, carefully curated texts, was a mess. AOL had a chaotic list of links to different portals, with stories that seemed to be written by journalists. There were encyclopedia entries describing seemingly random topics. There were chat rooms, where I could be connected with random, anonymous people around the world. And there were collections of files; one favorite of mine was sound clips from famous movies. My brother and I would wait an hour for one WAV file to download, then spend several more hours using the sound editor application in Windows 95 to reverse it, speed it up, making Arnold Schwarzenegger as the Terminator say “I’ll be back”, backwards, and like a chipmunk.

These two different experiences emerged from two very different information systemsinformation system: A process for coordinating people, data, and information technology in order to faciliate information creation, storage, and access. 1 1 Michael K. Buckland (1991). Information and information systems. ABC-CLIO.

What are information systems?

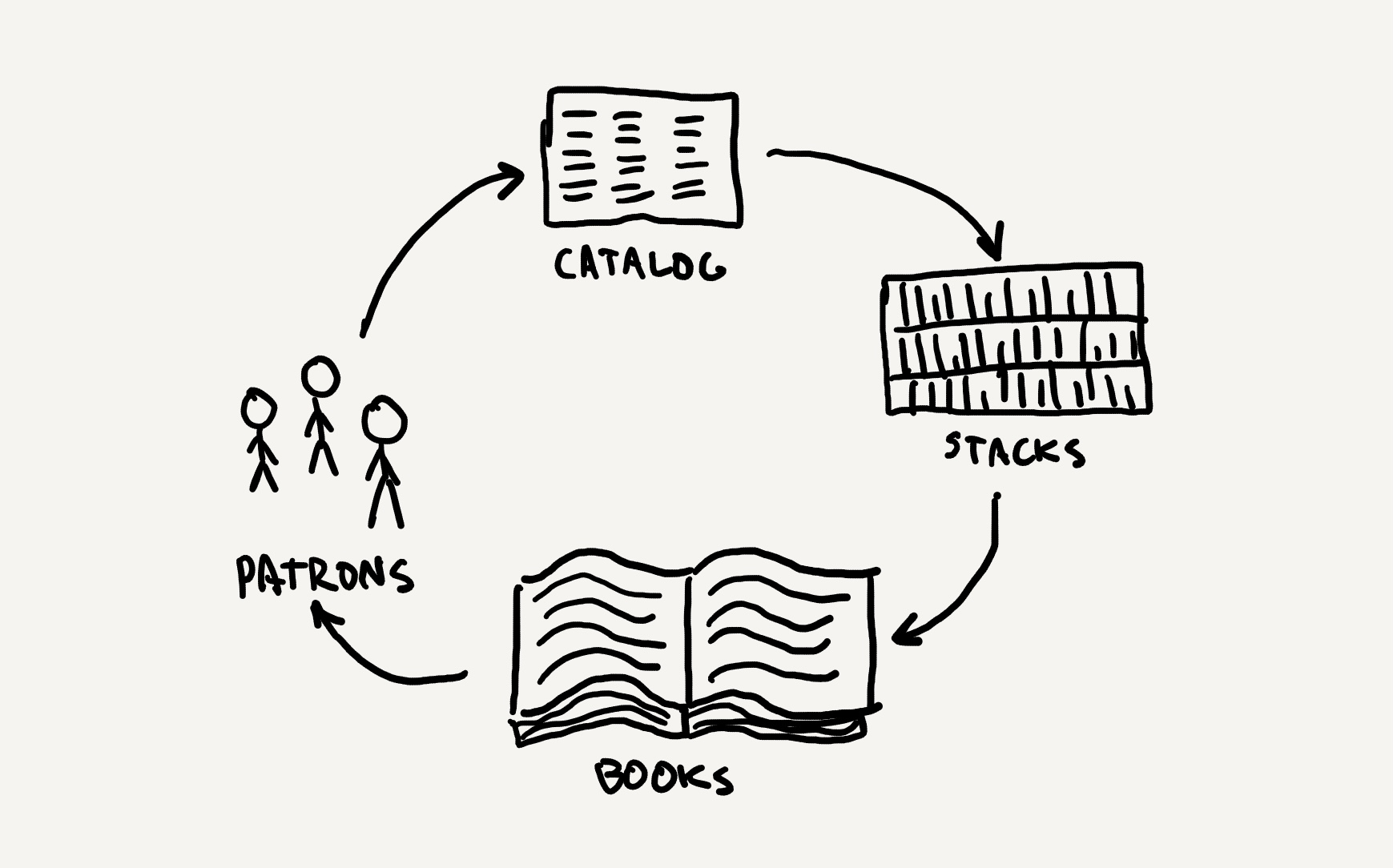

In contrast to information technology, which is some form of engineered device like the telephone or computer, information systemsinformation system: A process for coordinating people, data, and information technology in order to faciliate information creation, storage, and access. 1 1 Michael K. Buckland (1991). Information and information systems. ABC-CLIO.

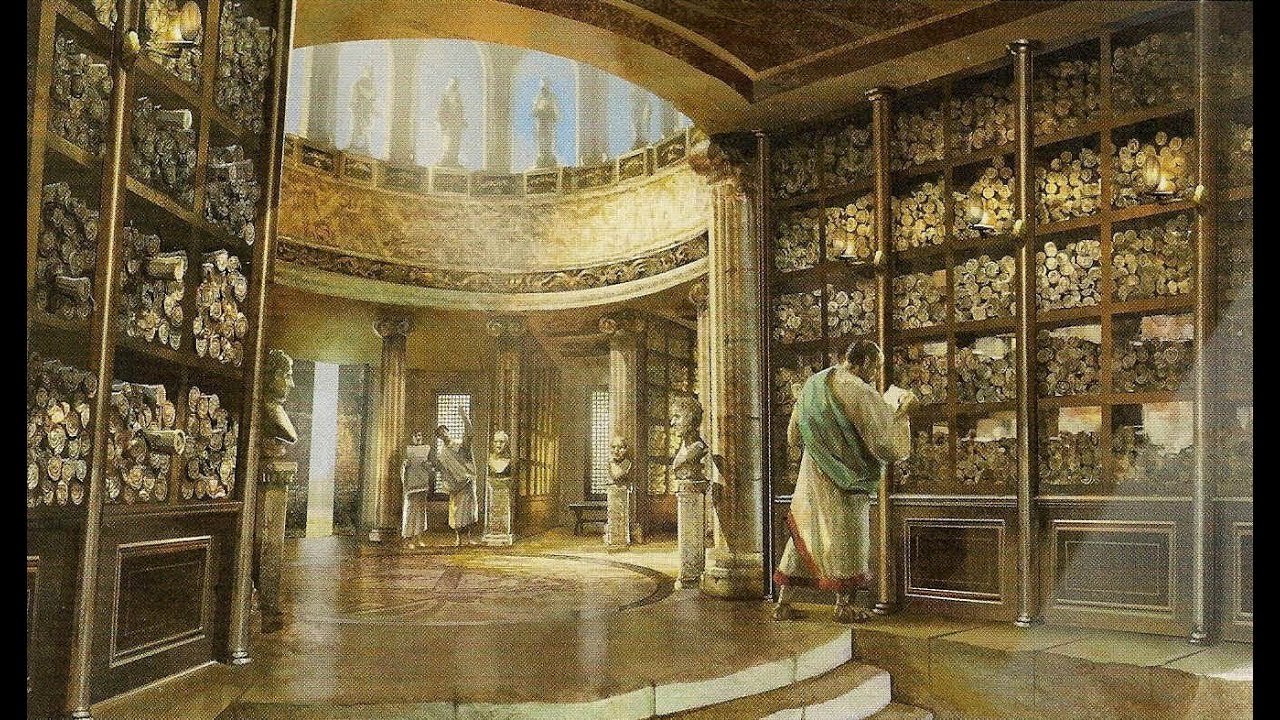

Information systems, like information technologies, have come in many forms in history. Consider, for example, the Great Library of Alexandria 3 3 Andrew Erskine (1995). Culture and power in ptolemaic Egypt: The Museum and Library of Alexandria. Greece & Rome.

Whereas libraries are systems that are optimized for archiving and retrieving documents from a collection, newspapers are a very different kind of system. In its modern form, newspapers were invented in Europe 7 7 Michael Schudson (1981). Discovering the news: A social history of American newspapers. Basic Books.

Maria DiCenzo (2003). Gutter politics: Women newsies and the suffrage press. Women's History Review.

Systems, of course, evolve. Whereas the Great Library of Alexandria relied on papyrus scrolls and handwritten copying, today’s modern libraries are far different. Consider, for example, the U.S. Library of Congress , widely considered to be the world’s most comprehensive record of human creativity and knowledge. It contains millions of books, printed materials, maps, manuscripts, photographs, films, audio and video recordings, prints and drawings—even every tweet on Twitter from 2006-2017, and selective tweets since. It acquires all of these through exchanges with libraries around the world, through gifts, and through purchase, adding thousands of new items each day, with a full staff curating and selecting items for inclusion in its permanent collection. It stores the books in dozens of buildings in Washington, D.C. and elsewhere; none of them are publicly accessible. However, because the library is a research library, any member of the public can search the online catalog of more than 18 million records, request an item, and read it at the library. Maintaining this library is far more involved than the Library of Alexandria 6 6 Gary Marchionini, Catherine Plaisant, and Anita Komlodi (1998). Interfaces and tools for the Library of Congress national digital library program. Information Processing & Management.

As should be clear from each of these examples, information systems are far more than a particular technology: they are processes that combine skilled people, systems of organization, and information technologies to provide access to information, each optimizing for particular kinds of information and information experiences.

The internet

No discussion of information systems would be complete without discussing the internet , perhaps the largest and most elaborate information system that humanity has ever created. And as with any system, it is a history of more than just technical innovation. It started in the 1950’s 4 4 Barry M. Leiner, Vinton G. Cerf, David D. Clark, Robert E. Kahn, Leonard Kleinrock, Daniel C. Lynch, Jon Postel, Larry G. Roberts, Stephen Wolff (2009). A brief history of the internet. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review.

Joseph C.R. Licklider, Robert W. Taylor (1968). The computer as a communication device. Science and technology.

When people do their informational work “at the console” and “through the network,” telecommunication will be as natural an extension of individual work as face-to-face communication is now... life will be happier for the on-line individual because the people with whom one interacts most strongly will be selected more by commonality of interests and goals than by accidents of proximity. ... communication will be more effective and productive, and therefore more enjoyable... there will be plenty of opportunity for everyone (who can afford a console) to find his calling, for the whole world of information, with all its fields and disciplines, will be open to him—with programs ready to guide him or to help him explore... Unemployment would disappear from the face of the earth forever, for consider the magnitude of the task of adapting the network’s software to all the new generations of computer, coming closer and closer upon the heels of their predecessors until the entire population of the world is caught up in an infinite crescendo of on-line interactive debugging.

Joseph C.R. Licklider, Robert W. Taylor (1968). The computer as a communication device. Science and technology.

The vision, while not perfect in its clairvoyance, laid out several hard problems that needed to be solved to realize the networked future: how to format and send messages reliably; where to store data; and most importantly, how to ensure everyone could have access to a computer to participate. This led to the U.S. APRANET project, which sought to solve many of these problems through government-funded research and innovation. This history is told by Robert Kahn, discussing the motivations behind the beginnings of the internet:

The first foundation was that the internet is a graph : a collection of nodes, each a computer, connected by edges, each some hardware allowing messages to be transmitted between computers. Getting information from one node to another requires finding a path from one node in the network to another. Therefore, when you access the internet on a phone, tablet, laptop, or desktop, your computer has to send a request to another computer for that information, and that request itself has to find a path to that computer, before that computer can respond with the data, sending it back along a path.

All of these back and forth messages between computers requires a protocol to organize communication. For example, when we send physical letters in the U.S. mail, there is a protocol: put a message in an envelope, write an address for where you want to send it, write a return address in case it cannot be delivered, put a stamp on it, then submit it to a post office or post office pickup location. The internet required something similar; Vint Cerf invented the protocol we use today in 1973, naming it TCP/IP . The TCP stands for Transmission Control Protocol , and defines how computers start a conversation with each other. In a simplified form, TCP defines two roles for computers on the internet: clients , which request information, and servers , which deliver it. TCP works in three phases:

- The server starts listening for connections.

- The client asks for a connection.

- The server acknowledges the request.

After this, data is sent in chunks called packets , which are a sequence of bytes defining where the information is coming from, where it is going, and various other information for checking whether the information has arrived intact, along with the data itself. After the data is received, the server indicates that it is done sending information, the client acknowledges that it was received intact and requests the connection be closed, and then the server closes the connection.

TCP, of course, is just one part of transmitting information. The other part in the acronym TCP/IP is IP , which stands for Internet Protocol . This defines how computers on the internet are identified. An IP address is a unique number representing a computer; all computers connected to the internet have one, though they may change and be shared. IP addresses are four 8-bit numbers and look something like this:

152.002.081.001 The first two chunks are a unique number assigned to the network your computer is connected to; the last two parts are a unique number on your network. More modern versions of IP addresses (IPv6) contain 128 bits, allowing for more uniquely identifiable addresses. These addresses ultimately end up encoded in TCP packets to indicate the source and destination of data.

If the internet was just a bunch of computers connected to each other via TCP/IP, it wouldn’t work very well. Every computer would need to know the IP address of every computer that it wanted to communicate with. And clearly, when we use computers today, we don’t have to know any IP addresses. The solution to this problem is two fold. First, we have routers , which are specialized computers that break up the internet into smaller networks, and are responsible for keeping records of IP addresses and finding paths for a packet to get to its destination. You probably have a router at home to connect to your internet service provider (ISP), which is essentially one big router that processes TCP requests from millions of customers. Second, we have domain name services , which are specialized computers that remember mappings between IP addresses and unique names ( www.seattle.gov ), which are organized into top level domains ( .gov ), domains ( seattle ), and subdomains ( www ). Your internet service provider also maintains DNS lookups, so you don’t have to memorize IP addresses. Combined, TCP, IP, DNS, and routers are what allow us to enter a simple domain like www.seattle.gov into a web browser, establish a connection to the UW web servers, request the front page of the Seattle city government website, receive that front page, close the connection, and then render the front page on our computer.

There is one more important detail: TCP/IP alone, plus some network hardware to connect computers to routers via ethernet cables or wireless protocols, is sufficient to create the internet. But it is not sufficient to create the web , which is actually an application built on top of the internet using yet more protocols. The most important of these, HTTP (hypertext transfer protocol) (or the encrypted version, HTTPS ), is how computers use TCP/IP to send and request entire documents between computers. It wasn’t invented until the early 1990’s. The basis of HTTP is simple: clients send a request for a particular document via a URL (uniform resource locator), which consists of a domain ( www.seattle.gov ) plus a pathway to the desired document ( /visiting-seattle ). When we combine the transfer protocol, the domain, and the path, we get https://www.seattle.gov/visiting-seattle , which specifies how the request will be formatted, which computer we want to send the request to (by name, which will be used to lookup an IP address on a DNS server), and which document on that computer we want ( /visiting-seattle ). If the computer has a web server running that knows how to handle HTTPS requests, it will use the path to retrieve the document, then send it back to the client.

Together, TCP, IP, routers, DNS, and HTTP, and their many versions and supporting hardware, make up the modern internet and web, and allow it to be as simple as typing in a URL and seeing a web page. Every computer on the internet must follow these protocols for any of this to work. And if anything goes wrong in the process, the internet will “break”:

- If your computer loses its wired or wireless connection to a router, it won’t be able to connect to other computers.

- If your router loses its connection to the rest of the internet (e.g., your ISP loses its connection), it won’t be able to send packets.

- If your router can’t find a path from your computer to the computer from which you’re requesting information, your request will “time out”, and result in an error.

- If the computer processing your request can’t find the document you’re requesting (e.g.,

https://www.seattle.gov/not-a-real-page), it will send an error. - If the web browser on the computer processing your request hangs or terminates, it won’t process requests.

- If the computer processing your request experiences a power outage, it won’t process requests.

Much of what industry calls the cloud is meant to deal with these reliability problems. The cloud is essentially a collection of large data centers distributed globally that contain large numbers of powerful computers that redundantly store large amounts of data. Computers then request that data for display, and send requests to modify that data, rather than storing the data locally. For example, when you edit a Google Doc, the document itself is not stored on your computer, but redundantly stored on many servers across the globe. If one of those data centers has a power outage, another data center will be there to respond, ensuring that you’ll rarely lose access. (Of course, when you go offline, you won’t have a copy of your data at all).

Is the internet the best information system?

Humanity has invented many forms of information systems in history, all with different strengths and weaknesses. But it is tempting to imagine that the internet, being the newest, is the best of them all. It is fast, it is relatively reliable, it connects us to nearly anyone, anywhere, and we can access nearly anything—data, information, even goods and services—by using search engines. When we compare this to older types of systems—word of mouth, libraries, newspapers—it is hard to argue that they are in any way superior, especially since we have replicated most of those systems on the internet in seemingly superior forms. News is faster, books are easier to get, and even informal systems like chatting with friends and sharing gossip, has never been more seamless and efficient.

But if we think about information systems in terms of qualities , it becomes clear that the internet is not always superior:

- Accuracy . Much of the data on the web is misleading or even false, which is far less true for information from carefully curated, edited, and fact-checked sources like books and leading newspapers, or from experts directly.

- Reliability . A print book doesn’t depend on electricity or a network of computers to operate. As long as the book is the only information you need, it’s much more reliable that a computer connected to the internet.

- Learnability . Learning to talk, whether verbally or non-verbally, is still easier for people to learn than the many skills required to operate a computer (mice, touch screens, keyboards, operating systems, applications, web browsers, URLs, buttons, links, routers, wifi, etc.).

Of course, the internet is superior in somethings: it wins in speed , as well as currency , which refers to how current information is. To the extent that humanity is only concerned with getting recent information quickly, then it is superior. But when one wants expert information, information from history, or private information that might only be stored in people’s memories or private archives, the internet is inferior. And more importantly, if you want to live life slowly, take in information in a measured, careful way, and have time to process its meaning, the speed and currency of the internet will be a distraction and nuisance. Thus, as with all designed things, the internet is optimized for some things, and fails at others.

Information systems, therefore, aren’t better or worse in the absolute sense, but better or worse for particular tasks. Choosing the best system for a particular task then isn’t just about choosing the latest technology, but carefully understanding the task at hand, and what types of systems might best support. And as society is slowly discovering, the internet might be fast, but it isn’t so good at tasks like helping people find credible information, learn online, or sustain local communities. In fact, it seems to be worse at those things, when compared to systems that rely on authoritiative, credible information, systems that center physically proximal teachers for learning, and physical spaces that bring communities together to connect.

Podcasts

These podcasts explore some of the strengths and weaknesses of modern information systems.

- Rabbit Hole, Episode 1, NY Times . Discusses YouTube as an information system, and the kinds of information experiences it excels at creating.

- Why the Vaccine Websites Suck, What Next TBD . Discusses the many policies, practices, and market dynamics that result in U.S. government websites being so poor in quality.

- Seduced by Substack, What Next TBD, Slate . Discusses why some journalists are shifting from traditional journalism to a paid newsletter model on Substack, and the tradeoffs of the new model for editorial oversight, labor, and chasing audience.

- Brown Box, Radiolab, WNYC Studios . Discusses the information systems used to rapidly provision online orders and some of inhumane work they cause. Also discusses the complexities of name changes for those with records of archived, credited work. (The reporter is transgender.)

- The Internet is a Luxury, Recode Daily, Vox . Discusses the digital divide and why most people in the world still don’t have access to the internet.

- 404: Podcast Not Found, Recode Daily, Vox . Discusses the exceptional difficulties of archiving content on the internet relative to other information systems.

References

-

Michael K. Buckland (1991). Information and information systems. ABC-CLIO.

-

Maria DiCenzo (2003). Gutter politics: Women newsies and the suffrage press. Women's History Review.

-

Andrew Erskine (1995). Culture and power in ptolemaic Egypt: The Museum and Library of Alexandria. Greece & Rome.

-

Barry M. Leiner, Vinton G. Cerf, David D. Clark, Robert E. Kahn, Leonard Kleinrock, Daniel C. Lynch, Jon Postel, Larry G. Roberts, Stephen Wolff (2009). A brief history of the internet. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review.

-

Joseph C.R. Licklider, Robert W. Taylor (1968). The computer as a communication device. Science and technology.

-

Gary Marchionini, Catherine Plaisant, and Anita Komlodi (1998). Interfaces and tools for the Library of Congress national digital library program. Information Processing & Management.

-

Michael Schudson (1981). Discovering the news: A social history of American newspapers. Basic Books.