Information + social

When I was in middle school, there were no smartphones and there was no internet. Friendship, therefore, was about proximity: I eagerly woke up and rushed to the bus stop each morning not to get to school, but to see my friends, all of whom lived within a mile of my house. Lunch was always the highlight of the day, where we could share our favorite moments of the latest Pinky and the Brain skit on Animaniacs , gossip about our teachers, and make plans for after school. On the bus ride home, we would chart out our homework plans, so we could reunite at 4 or 5 pm to play Super Nintendo together, play basketball at the local primary school playground, or ride our bikes to the corner store for candy. If we were feeling lonely, we might head to our kitchens to our wired landline phone, call each other’s houses, politely ask whoever answered to give to the phone to our friend, and covertly coordinate our next moves. But our conversations were always in code, knowing full well that our parents or siblings might be listening on another phone, since they all shared the same line.

To be social in the early 1990’s in the United States meant to be together, in the same space, or on the phone, likely with no inherent privacy. This time, of course, was unlike the world before the phone, in that nearly all communication was face to face; and it is unlike today, where almost all communication is remote and often asynchronous. The constant in all of these eras is that to be social is to exchange information, and that we use information and communications technologies (ICTs) to facilitate this exchange. In this chapter, we’ll discuss the various ways that information intersects with the social nature of humanity, reflect on how technology has (and hasn’t) changed communication, and raise questions about how new information technologies might change communication further.

Information and Communication

Information, in the most abstract sense, is a social phenomenon. All human communication is social in that it involves interactions between people. Writing, data, and other forms of archived information are social, in that they capture information that might have otherwise been communicated in forms separate from another person. Even biological information like DNA is social, in that we have elaborate and diverse social norms about how we share our DNA with each other through reproduction. Information is constructed socially, in that we create it with other people, shaped by our shared values, beliefs, practices, and knowledge; and we create it for the purpose shaping the values, beliefs, and practices, and knowledge of other people.

Similarly, information systems, including all of those intended for communication, are sociotechnical , in that they involve both social phenomena such as communication, as well as technology to facilitate or automate that communication. Libraries are social in that they are shared physical spaces for exchanging and sharing knowledge. The internet is social in that it is a shared virtual space for exchanging and sharing knowledge. Even highly informal information systems, like a group of friends chatting around a table, are sociotechnical, in that they rely on elaborate systems of verbal and non-verbal communication to facilitate exchange 2 2 Michael Argyle (1972). Non-verbal communication in human social interaction. Cambridge University Press.

Our social interactions around information can vary along some key dimensions, broadly shaping what is known as social presence 27 27 John Short, Ederyn Williams, Bruce Christie (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons.

Each information technology has unique properties along these dimensions. For example, consider two popular forms:

- Face-to-face communication has high potential for intimacy, immediacy, and efficiency, as it affords multiple parallel channels for exchange, including speech, non-verbal cues, eye contact, facial expressions, and posture. It is also synchronous, in that the delay between sending a message and receiving it is effectively instantaneous because of the high speed of light and sound. And by using other information technology—paper, pens, whiteboards, smartphones, tablets—there is even richer potential to communicate efficiently and intimately through multiple media.

- Texting strips away most of the features of face-to-face communication, leaving an asynchronous stream of words, symbols (e.g., emoji), and more recently, images and video. It can achieve a different kind of intimacy because of its privacy, though it has many fewer channels in which to do this, and often results in miscommunication, especially of emotional information 31 31

Sarah Wiseman, Sandy JJ Gould (2018). Repurposing emoji for personalised communication: Why🍕 means “I love you”. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

. Because it is often asynchronous and usually at a distance, there is more time between exchanges, and therefore reduced immediacy. Moreover, because of the reduced channels, may be less efficient for particular kinds of information that are more easily conveyed with speech, gestures, or drawings.

These basic ideas in information and communication are just a fraction of the insights in numerous fields of research. Communication 5 5 John Fiske (2010). Introduction to Communication Studies. Routledge.

William McDougall (2015). An Introduction to Social Psychology. Psychology Press.

John R. Schermerhorn, Jr., Richard N. Osborn, Mary Uhl-Bien, James G. Hunt (2011). Organizational Behavior. Wiley.

Manoj Parameswaran, Andrew B. Whinston (2007). Social computing: An overview. Communications of the Association for Information Systems.

Communities

One place that these foundational aspects of communication play out is in communities , which may be anything from groups of people with strong ties to much larger groups that share some affinity, such as an interest, identity, practice, or belief system 29 29 Etienne Wenger (1999). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

Communities relate to information in that much of what communities do is exchange information. Communities curate information with each other to promote learning and awareness, like active Wikipedia contributors create shared identity and practices around curating knowledge about special interests 24 24 Christian Pentzold (2010). Imagining the Wikipedia community: What do Wikipedia authors mean when they write about their ‘community’?. New Media & Society.

Lena Mamykina, Bella Manoim, Manas Mittal, George Hripcsak, and Björn Hartmann (2011). Design lessons from the fastest Q&A site in the west. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Shruti Phadke, Mattia Samory, and Tanushree Mitra (2020). What Makes People Join Conspiracy Communities? Role of Social Factors in Conspiracy Engagement. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

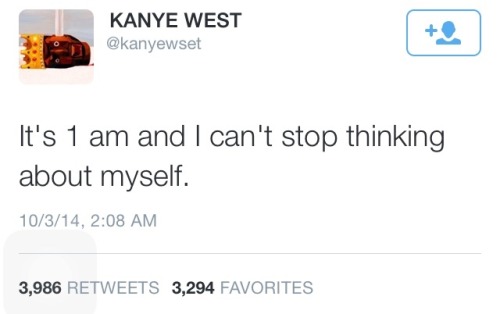

The internet has led to a rapid exploration of information technologies to support community, revealing two major types of community supports. One support is broadcasting . Much like newspapers, radio, and television, online social media is often used to broadcast to community, where one person or a group of people broadly disseminate information to a broader community. It includes Usenet, which were the threaded discussion forums that shaped the internet and inspired later websites like Slashdot, Digg, and Reddit 10 10 Michael Hauben, Ronda Hauben, Thomas Truscott (1997). Netizens: On the History and Impact of Usenet and the Internet. Wiley.

Bonnie A. Nardi, Diane J. Schiano, and Michelle Gumbrecht (2004). Blogging as social activity, or, would you let 900 million people read your diary?. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

Michael Bernstein, Andrés Monroy-Hernández, Drew Harry, Paul André, Katrina Panovich, and Greg Vargas (2011). 4chan and/b: An Analysis of Anonymity and Ephemerality in a Large Online Community. AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media.

Binny Mathew, Anurag Illendula, Punyajoy Saha, Soumya Sarkar, Pawan Goyal, and Animesh Mukherjee (2020). Hate begets Hate: A Temporal Study of Hate Speech. ACM Proceedings of Human-Computer Itneraction.

Other communities are more focused on discourse , where communication is not primarily about broadcasting from one to many, but more mutually interactive communication and conversation. Most notably, since its launch, Facebook has been seen as a place to maintain close relationships, talking about shared interests, celebrating life milestones, or providing support in trying times 14 14 Cliff Lampe, Nicole B. Ellison, and Charles Steinfield (2008). Changes in use and perception of Facebook. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

Andrea Meier, Elizabeth Lyons, Gilles Frydman, Michael Forlenza, and Barbara Rimer (2007). How cancer survivors provide support on cancer-related Internet mailing lists. Journal of Medical Internet Research.

Oliver L. Haimson, Justin Buss, Zu Weinger, Denny L. Starks, Dykee Gorrell, and Briar Sweetbriar Baron (2020). Trans Time: Safety, Privacy, and Content Warnings on a Transgender-Specific Social Media Site. ACM Proceedings on Human-Computer Interaction.

It is rare that communities last forever. Some of the key reasons communities fade include 4 4 Casey Fiesler, Brianna Dym (2020). Moving Across Lands: Online Platform Migration in Fandom Communities. ACM Proceedings of Human-Computer Interaction.

- Its members’ needs and interests change, and so they leave one community for another.

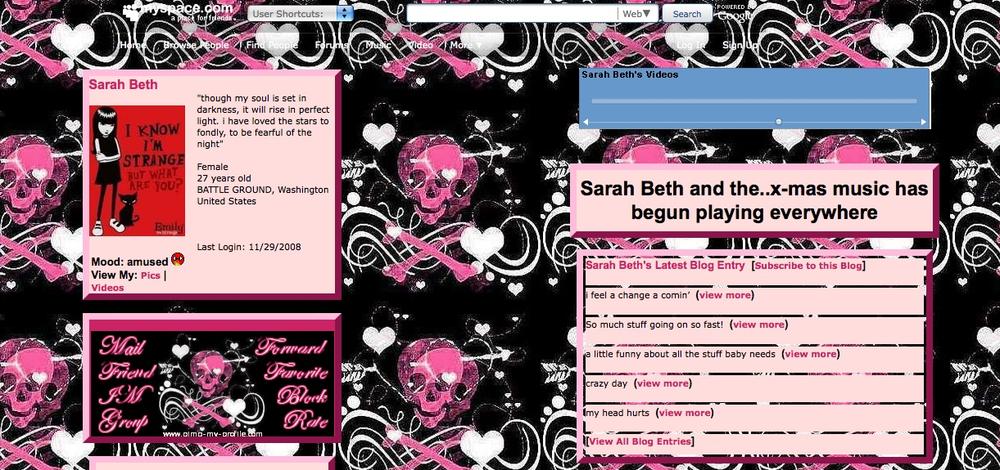

- A platform’s underlying information technology of a platforms decays, reducing trust in the archiving of information and the availability of the platform, resulting in migration to new platforms that are better maintained.

- Platform maintainers make design changes that are disruptive to community norms, such as the infamous 2018 Snapchat redesign that condensed stories and snapchats into a single “Friends” page.

- Platform policies evolve to become hostile to a community’s values, or a community’s values evolve and policies do not. For example, many experience harassment on Twitter, struggling to maintain block lists, and therefore leave 11 11

Shagun Jhaver, Sucheta Ghoshal, Amy Bruckman, and Eric Gilbert (2018). Online harassment and content moderation: The case of blocklists. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction.

.

These demonstrate that while a community’s communication is key, so are the underlying information systems designed and maintained to support them.

One key design choice in online communities is how to handle content moderation. All communities moderate somehow; at a minimum, platforms may only allow people with accounts to post, or may disallow content that is illegal where the community or platform operates. Most social media companies have a set of rules that govern what content is allowed, and they enforce those rules to varying degrees. For example, Twitter does not currently allow violent threats, promotions of terrorism, encouragement of suicide, doxxing, or harassment. However, it does allow other content, such as gaslighting , which is a form of abuse that makes victims seem or feel “crazy” 28 28 Paige L. Sweet (2019). The sociology of gaslighting. American Sociological Review.

Kaitlin Mahar, Amy X. Zhang, David Karger (2018). Squadbox: A Tool to Combat Email Harassment Using Friendsourced Moderation. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

Collaboration, Coordination, and Crowds

Whereas communities often bring people together to share information about interests and identities, work is an entirely different form of social interaction, bringing people together to accomplished shared goals. As with communities, information and information technologies are central to work.

One way that information is central is that information facilitates collaboration , in which a group of people together to achieve a shared goal. Collaboration includes activities like pair programming , in which software developers write code together, making joint decisions, helping each other notice problems, and combining their knowledge to improve the quality of code 30 30 Laurie A. Williams, Robert R. Kessler (2000). All I really need to know about pair programming I learned in kindergarten. Communications of the ACM.

Young-Wook Jung, Youn-kyung Lim, and Myung-suk Kim (2017). Possibilities and limitations of online document tools for design collaboration: The case of Google Docs. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

Darren Gergle, Robert E. Kraut, and Susan R. Fussell (2013). Using visual information for grounding and awareness in collaborative tasks. Human–Computer Interaction.

Whereas collaboration is about people in tandem toward a shared goal, coordination is about people working separately, and often asynchronously toward a shared goal, separated by time and space. For example, coordination includes large teams of software developers independently working on an application, but eventually integrating their work into a coherent whole 25 25 Rachel Potvin, Josh Levenberg (2016). Why Google stores billions of lines of code in a single repository. Communications of the ACM.

Geraldine Fitzpatrick, Gunnar Ellingsen (2013). A review of 25 years of CSCW research in healthcare: contributions, challenges and future agendas. Computer Supported Cooperative Work.

In general, information technologies struggle to support collaboration and coordination, especially in conditions like remote work where the baseline capacity for communication is low. Distance work, for example, really only succeeds when groups have high common ground, loosely coupled work with few dependencies, and a strong commitment to collaboration technologies, reducing the need for synchronous communication 21 21 Gary M. Olson, Judith S. Olson (2009). Distance matters. Human-Computer Interaction.

Aniket Kittur, Jeffrey V. Nickerson, Michael Bernstein, Elizabeth Gerber, Aaron Shaw, John Zimmerman, Matt Lease, and John Horton (2013). The future of crowd work. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

Information technology has struggled to prevent these strains for many reasons. First and foremost, research is clear on what aspects of face-to-face communication are necessary and why they are necessary, but even after decades of research, technology simply cannot support them 1 1 Mark S. Ackerman (2000). The intellectual challenge of CSCW: the gap between social requirements and technical feasibility. Human-Computer Interaction.

Organizations are also often ineffective at deploying collaboration tools 8 8 Jonathan Grudin (1988). Why CSCW applications fail: problems in the design and evaluation of organizational interfaces. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

- There are disparities between who does the work and who benefits. For example, using meeting scheduling software that allows the scheduler to easily see busy status helps the scheduler, but requires everyone else to carefully maintain their busy status.

- Collaboration tools require critical mass. For example, if only some people on your team adopts Slack, Slack is less useful, because you don’t get the information you need from the entire team.

- Collaboration tools don’t handle exceptions well. For example, sharing a Google Doc with someone without a Google account either requires exporting it, opening up permissions, or not sharing it with them at all.

Thus, despite many decades of innovation and adoption in industry, working together still works best face-to-face in the same physical space.

Clearly, information technology has changed how we communicate, and in some ways, it has even changed what we communicate, allowing us to share more than words. And yet, as we have seen throughout this chapter, it hasn’t really changed the fundamental challenges of communication, nor has it supplanted the richness of face-to-face communication. What it has done is expanded the ways we communicate, and deepened our understanding of what makes communication work, challenging us to adapt to an ever more complex array of ways of being social.

Podcasts

- Ghost in the Machine, On the Media . Discusses the possible necessary limits of free speech, ideas from planning that could shape future social media platforms, and the often problematic role of science fiction in shaping online platforms.

- Can Big Tech Make Sure That 2020 Is Not 2016?, Sway . Discusses how social media platforms are amending policies around political advertising and disinformation.

- You Missed a Spot, On the Media . Discusses content moderation, deplatforming, free speech, and the future of social media.

- I Love Section 230. Got a Problem With That?, The Argument, NY Times . A debate on Section 230, the left’s desire for more aggressive moderation, the right’s desire for less, and the surprising ways that the policy has created a marketplace for online speech.

- Restoring Justice Online, On the Media . Discusses conflict and harassment online and how methods of restorative justice hold promise to rehabilitate online communities suffering from interpersonal conflict.

- The Substack Bros & Teen Vogue, Cancel Me Daddy, Katelyn Burns and Oliver-Ash Kleine . Discusses the resignation of Teen Vogue’s new editor due to her anti-Asian racist adolescent tweets and the controversy at Substack in which ant-trans writers are being recruited with large writing grants using the revenue generated partly by trans Substack writers.

References

-

Mark S. Ackerman (2000). The intellectual challenge of CSCW: the gap between social requirements and technical feasibility. Human-Computer Interaction.

-

Michael Argyle (1972). Non-verbal communication in human social interaction. Cambridge University Press.

-

Michael Bernstein, Andrés Monroy-Hernández, Drew Harry, Paul André, Katrina Panovich, and Greg Vargas (2011). 4chan and/b: An Analysis of Anonymity and Ephemerality in a Large Online Community. AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media.

-

Casey Fiesler, Brianna Dym (2020). Moving Across Lands: Online Platform Migration in Fandom Communities. ACM Proceedings of Human-Computer Interaction.

-

John Fiske (2010). Introduction to Communication Studies. Routledge.

-

Geraldine Fitzpatrick, Gunnar Ellingsen (2013). A review of 25 years of CSCW research in healthcare: contributions, challenges and future agendas. Computer Supported Cooperative Work.

-

Darren Gergle, Robert E. Kraut, and Susan R. Fussell (2013). Using visual information for grounding and awareness in collaborative tasks. Human–Computer Interaction.

-

Jonathan Grudin (1988). Why CSCW applications fail: problems in the design and evaluation of organizational interfaces. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

-

Oliver L. Haimson, Justin Buss, Zu Weinger, Denny L. Starks, Dykee Gorrell, and Briar Sweetbriar Baron (2020). Trans Time: Safety, Privacy, and Content Warnings on a Transgender-Specific Social Media Site. ACM Proceedings on Human-Computer Interaction.

-

Michael Hauben, Ronda Hauben, Thomas Truscott (1997). Netizens: On the History and Impact of Usenet and the Internet. Wiley.

-

Shagun Jhaver, Sucheta Ghoshal, Amy Bruckman, and Eric Gilbert (2018). Online harassment and content moderation: The case of blocklists. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction.

-

Young-Wook Jung, Youn-kyung Lim, and Myung-suk Kim (2017). Possibilities and limitations of online document tools for design collaboration: The case of Google Docs. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

-

Aniket Kittur, Jeffrey V. Nickerson, Michael Bernstein, Elizabeth Gerber, Aaron Shaw, John Zimmerman, Matt Lease, and John Horton (2013). The future of crowd work. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

-

Cliff Lampe, Nicole B. Ellison, and Charles Steinfield (2008). Changes in use and perception of Facebook. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

-

Kaitlin Mahar, Amy X. Zhang, David Karger (2018). Squadbox: A Tool to Combat Email Harassment Using Friendsourced Moderation. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

-

Lena Mamykina, Bella Manoim, Manas Mittal, George Hripcsak, and Björn Hartmann (2011). Design lessons from the fastest Q&A site in the west. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

-

Binny Mathew, Anurag Illendula, Punyajoy Saha, Soumya Sarkar, Pawan Goyal, and Animesh Mukherjee (2020). Hate begets Hate: A Temporal Study of Hate Speech. ACM Proceedings of Human-Computer Itneraction.

-

William McDougall (2015). An Introduction to Social Psychology. Psychology Press.

-

Andrea Meier, Elizabeth Lyons, Gilles Frydman, Michael Forlenza, and Barbara Rimer (2007). How cancer survivors provide support on cancer-related Internet mailing lists. Journal of Medical Internet Research.

-

Bonnie A. Nardi, Diane J. Schiano, and Michelle Gumbrecht (2004). Blogging as social activity, or, would you let 900 million people read your diary?. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

-

Gary M. Olson, Judith S. Olson (2009). Distance matters. Human-Computer Interaction.

-

Shruti Phadke, Mattia Samory, and Tanushree Mitra (2020). What Makes People Join Conspiracy Communities? Role of Social Factors in Conspiracy Engagement. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing.

-

Manoj Parameswaran, Andrew B. Whinston (2007). Social computing: An overview. Communications of the Association for Information Systems.

-

Christian Pentzold (2010). Imagining the Wikipedia community: What do Wikipedia authors mean when they write about their ‘community’?. New Media & Society.

-

Rachel Potvin, Josh Levenberg (2016). Why Google stores billions of lines of code in a single repository. Communications of the ACM.

-

John R. Schermerhorn, Jr., Richard N. Osborn, Mary Uhl-Bien, James G. Hunt (2011). Organizational Behavior. Wiley.

-

John Short, Ederyn Williams, Bruce Christie (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons.

-

Paige L. Sweet (2019). The sociology of gaslighting. American Sociological Review.

-

Etienne Wenger (1999). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press.

-

Laurie A. Williams, Robert R. Kessler (2000). All I really need to know about pair programming I learned in kindergarten. Communications of the ACM.

-

Sarah Wiseman, Sandy JJ Gould (2018). Repurposing emoji for personalised communication: Why🍕 means “I love you”. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.