One of the things I love about being a marine biologist is sometimes I will pause and consider the absurdity of what I am doing at that moment. This week’s example was our trip to the Puget Sound Restoration Fund‘s hatchery in Manchester, where we learned how to dope native oysters and steal their embryos.

Why on earth would we do that to oysters? We are beginning our Washington Sea Grant-funded project to track native oyster larvae to inform the restoration efforts of PSRF. In order to do this work, we will need to sample the shelled larvae that are reared for a week or so within the shell of the adult mother oyster from dozens of sites around Puget Sound. Our past work has shown that only a few of the adults are holding larvae, or “brooding” at any one time, on the order of 10-15%. And we will need to find and sample twenty animals from each site. Until recently, we collected these samples by sacrificing the oysters, shucking them open and looking for the larvae. You can quickly see that we’d need to kill 200 or so adults from each of our many sites to get to that number, amounting to thousands of Olympia oysters, a State Candidate for the Washington Species of Concern list.

Luckily, a student named Kate Jackson, working with the Roberts Lab at UW School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, has refined a method to anesthetize the oysters, causing them to open their shells enough to wash the larvae out harmlessly. This technique was used extensively by Jake Heare, a graduate student in that lab, who was gracious enough to meet us in Manchester to teach us the technique.

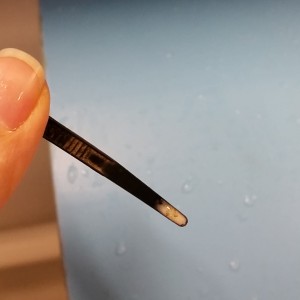

Members of our team got together to learn how it’s done. Essentially, the oysters are soaked in Epsom salts for some time, causing them to get very, very mellow. Then we look inside the gaping shell, or use a cable tie to gently sample the inside of the mantle cavity, the fleshy part inside of the shell. If embryos or larvae are there, we will see a creamy goo on the tip of the cable tie. Then a gentle stream of water is all that is needed to remove the babies. A few minutes later, the adult oysters will recover and go back to their usual tight-shelled style. Jake has done quite a bit of testing and has found no ill effects on the adults after recovery.

After years of talking and writing about our project, it was great to finally get our hands wet and work on the nitty-gritty details of our methods. It’s the small things that make or break the success of any field research effort, and getting together to calibrate them is vital.

And ultimately, we’re pleased that there is a viable alternative to having to sacrifice a few thousand of the species we are trying to restore.

Pingback:Hands on demo – knocking out oysters for science | Roberts Lab

Great post and video! Jake also has the specifics of the protocol in his preprint: Evidence of Ostrea lurida (Carpenter 1864) population structure in Puget Sound, WA – available at https://peerj.com/preprints/704/

Didn’t know they had live larvae inside their shells. We could call them viviparous then? I always thought (but never really inquired) that oysters like fish used something like eggs that would get fertilized intra- or extracorporally. What I have read though increasingly is that there are a lot of restoration projects to bring oysters back to their earlier natural habitats in US sea-fronts, even New York and other “unlikely” places.

Hi Oona. I wouldn’t use the term viviparous, which is usually used more with vertebrates that provide some sort of nutrition to their offspring. Oly oysters hold their early offspring in their mantle cavity, which is inside of the shell but outside of the body mass and exposed to the external world when mom opens her shell. Fertilization occurs there as well, after mom produces eggs that are kept in the mantle cavity and fertilizes them by taking up sperm packets through her siphon.

It’s an interesting question though, and I’ve asked a few colleagues their opinions before I answered and it generated some good discussion.

Yes, there are lots of efforts to restore our native Olympia oyster from southern California to British Columbia, as well as similar efforts on the East Coast for Eastern Oysters. For more info about some active programs check out:

Puget Sound

Oregon

San Francisco Bay Region

Southern California

Chesapeake

New York (Billion Oyster Project)

Much work being done, but much work left to do!