During this past year a series of hatchery-based environmental conditioning activities (referred to as hardening) were completed with oysters out-planted onto three farms to evaluate performance. Additionally, climate resiliency was assessed in hardened oysters under controlled conditions.

Farm Outplanting

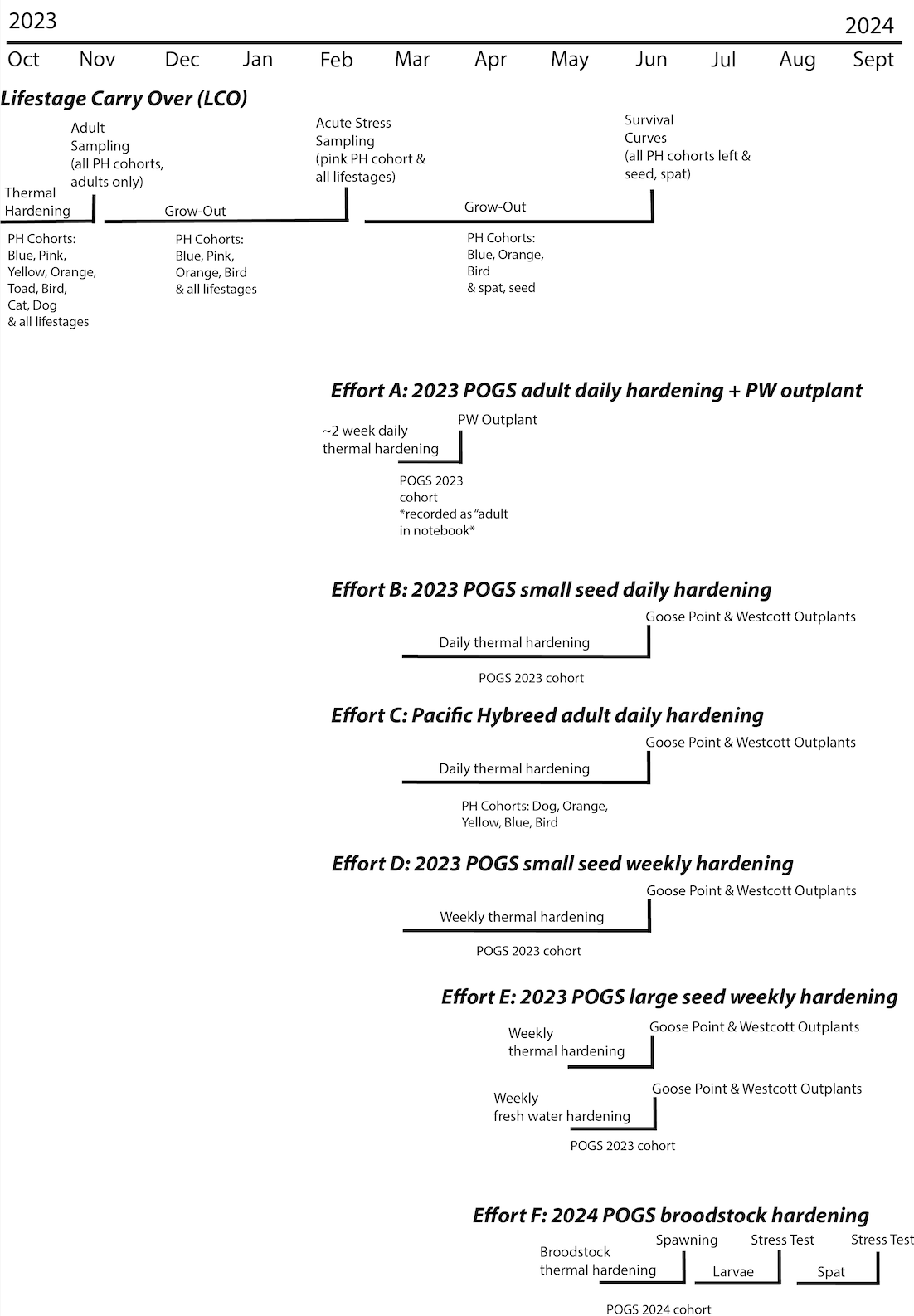

Early in the season, a cohort of oysters were subject to (a) daily thermal hardening for approximately two weeks prior to out planting in hanging bags on a farm in Sequim Bay, alongside a control group. These oyster will be assessed in early Autumn 2024. Later in the season oysters were subjected to a more diverse series of hardening conditions with oyster split between two commercial farms, one located in Willapa Bay and a second in the San Juan Islands. The combination of age classes and hardening conditions were as follows: b) small seed / daily thermal hardening, c) adult / daily thermal hardening, d) small seed / weekly thermal hardening, e1) large seed / weekly thermal hardening, e2) large seed / weekly zero salinity hardening. These hardening activities spanned from several weeks to months. For all hardening efforts controls were also outplanted. Oysters out planted in Willapa Bay will be assessed for survival and growth in early September 2024. Oysters out planted in the San Juan Islands have be subject to more routine monitoring. At this site we are currently observing a trend where oysters subjected to the daily hardening regime are surviving better than controls.

Physiological Assessment 1

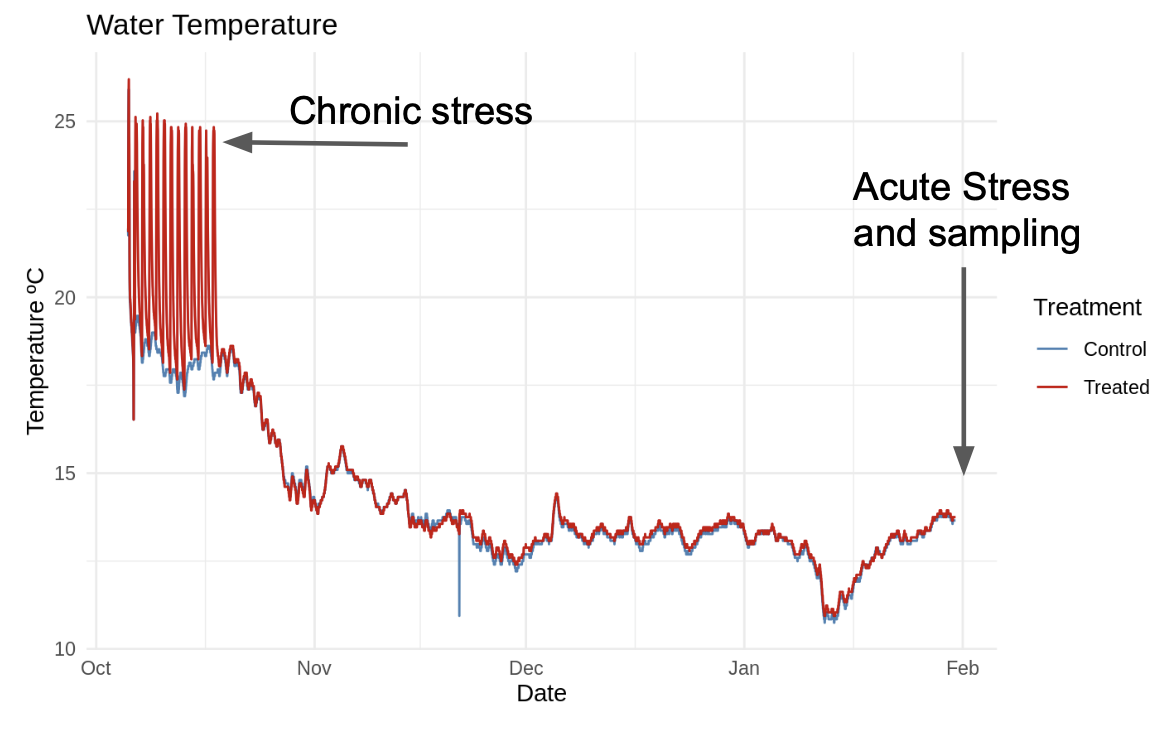

To assess the effectiveness of hardening within a hatchery setting, four ages classes of oysters were examined: adults (40-100mm), juveniles (20-55mm), seed (6-15mm), and spat ()1-6mm). In order to assess hardening potential and environmental memory, oysters were subject to an initial chronic temperature stress, then subjected to a secondary stress to see if the response to secondary stress was impacted by initial exposure. During the chronic temperature stress period, oysters from each age class were exposed to a daily 25ºC temperature spike. This repeated for 14 days starting on October 1. Control oysters from each cohort were maintained at an ambient temperature of approximately 17ºC during the same time period.

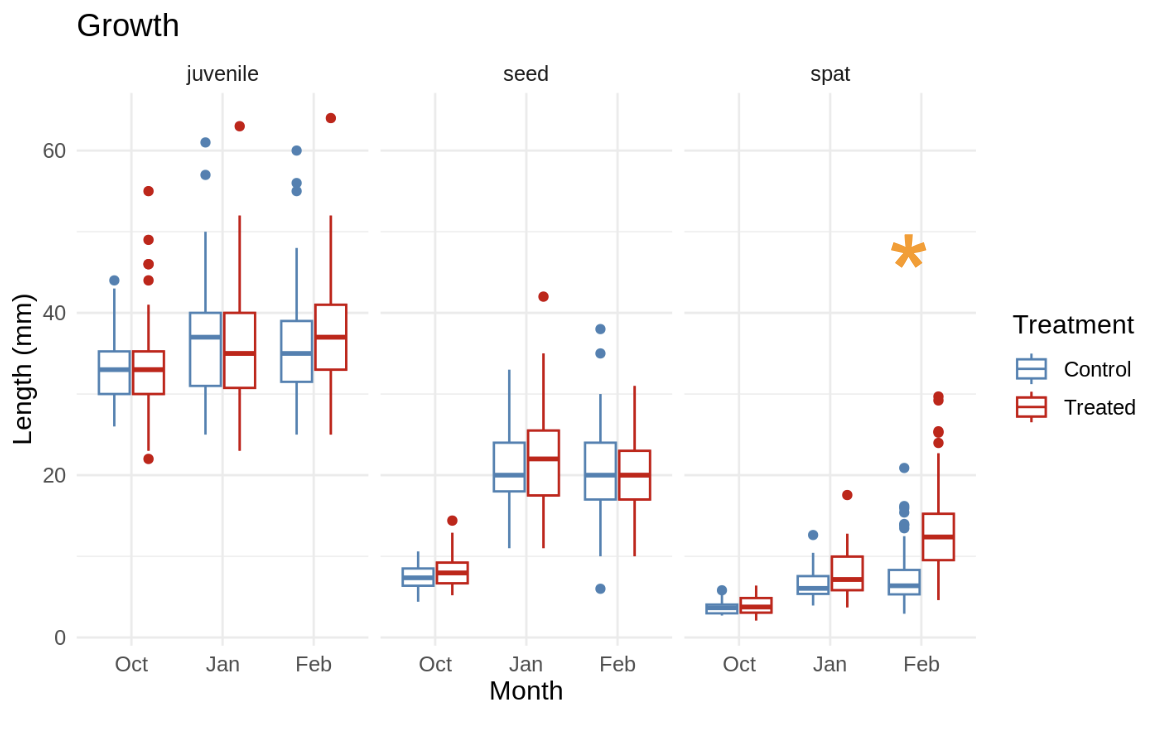

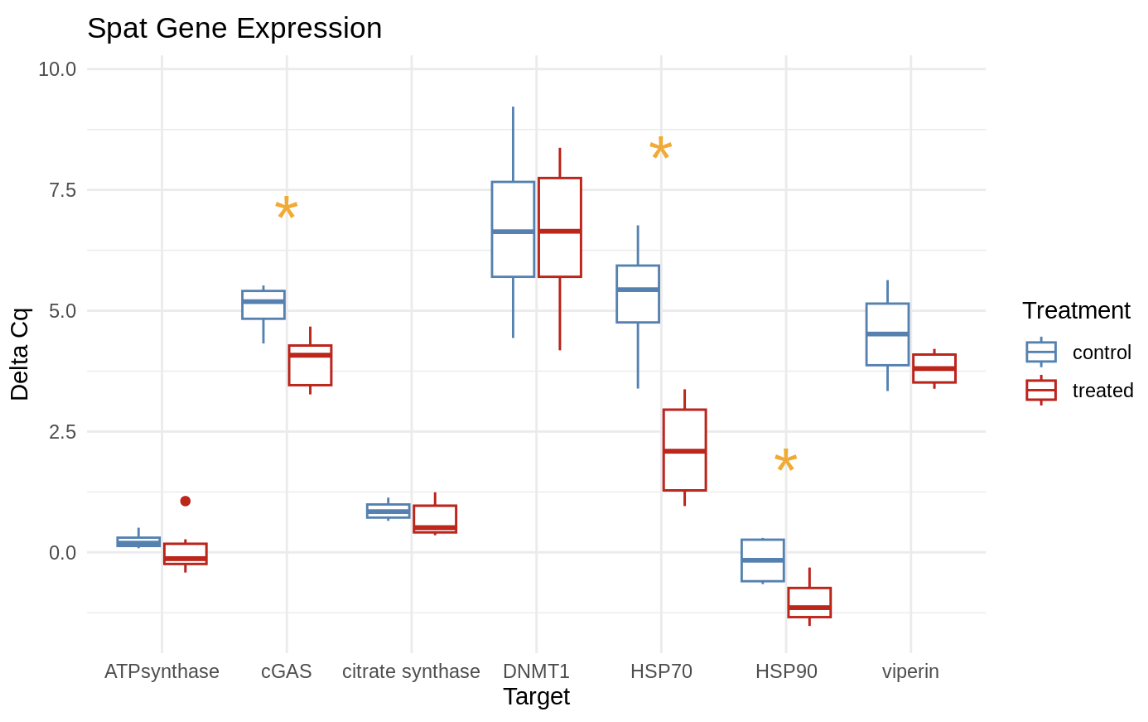

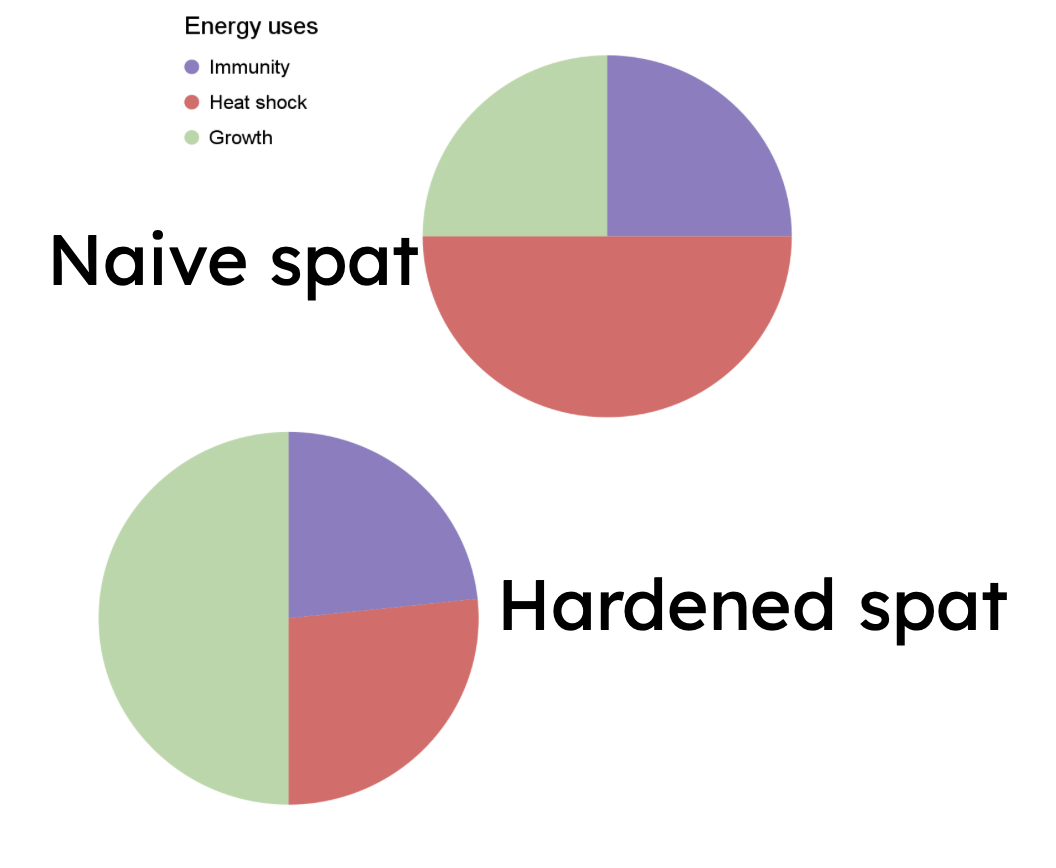

Adult oysters in stress conditions were also subject to mechanical stress at day 1, 7, and 48, which was induced by 15 minutes. At day 147 (7 weeks after initial chronic stress), both stressed and non-stressed adult, juvenile, spat, and seed were subjected to a secondary stress of 30 minutes in 32ºC. Gill tissue was sampled immediately after and placed into RNAlater. Spat and seed that were too small to dissect gill tissue were sampled whole with all tissue used in gene expression assays. To date we have analyzed gene expression data from seed and spat. There was no mortality during this trial. Hardening increased growth (compared to controls) in spat. Further there was a reduced transcriptional response in spat. These data suggest temperature hardening of spat could result in a resiliency to later temperature stress whereby energy resources could favor growth.

Physiological Assessment 2

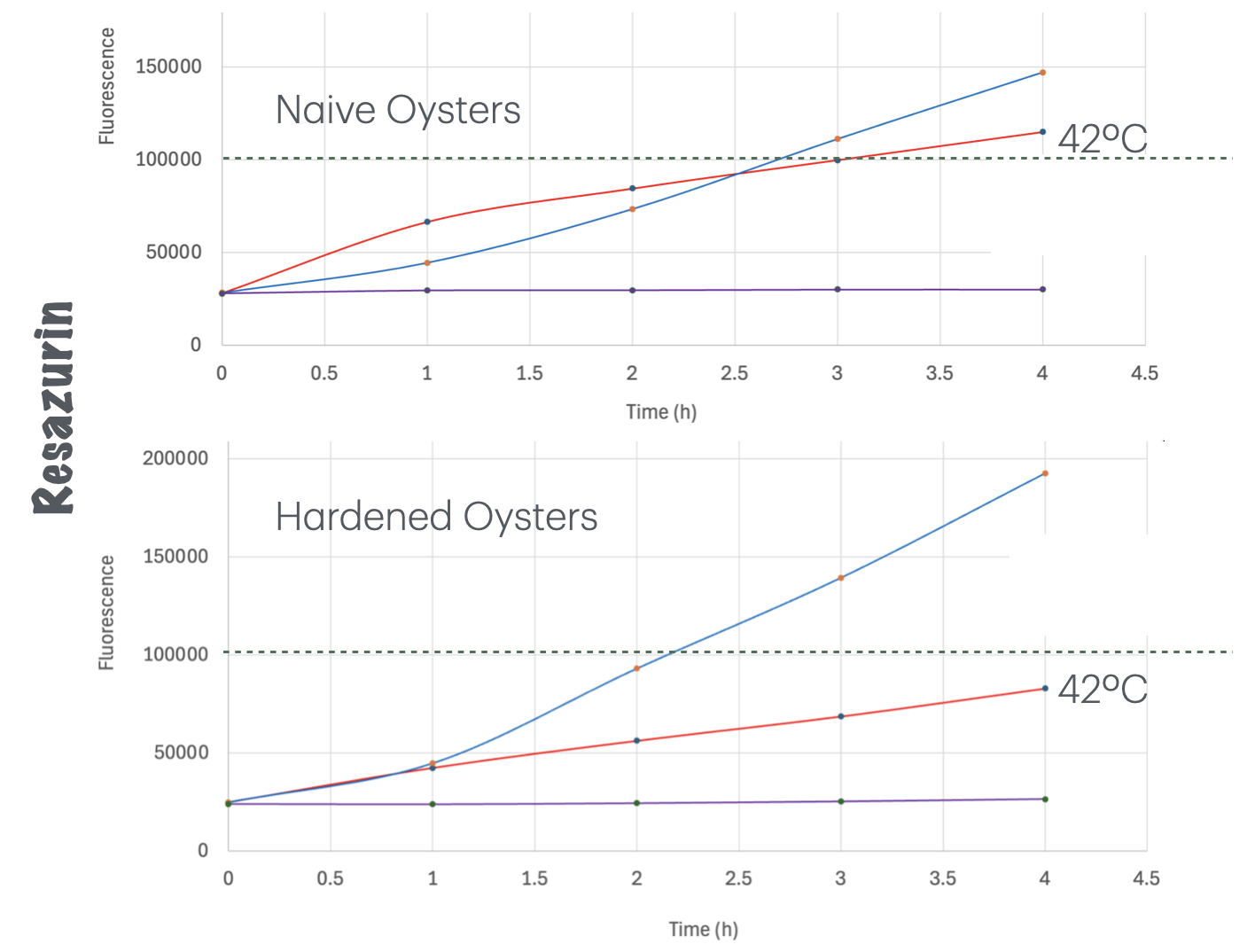

In a second experimental regime, juvenile oysters were subjected to four hardening conditions 1) high temperature (35°C), 2) high temperature and freshwater, 3) freshwater, and 4) poly I:C immersion. These were exposures that occurred every other day for about 3 weeks. Approximately 1 month after hardening, oysters were brought to the lab and subjected to metabolic assessment using resazurin at 18°C and 42°C. Resazurin is a dye that is commonly used in cell viability, and it works by changing color as an organism consumes oxygen. Survival was assessed during the resazurin assay and 24 hours later. To date, our analysis suggests metabolic activity of the 42°C oysters was higher in the control oysters than previously hardened oysters. In the near future we will assess the relationship of metabolic activity and survival however it appears higher metabolic rate directly correlates with mortality. Taken together these sets of controlled experiments suggest hardening does have an impact on resiliency, though dependent on age, hardening duration, and subsequent environmental conditions.