I’ve been thinking about writing this post for a very long time. I want to share my experience with chronic illness.

My illness has caused me a lot of feels over the years. Frustration at how much work it takes to manage. Resentment toward people who don’t have similar struggles (though of course I don’t actually know what’s happening in others’ lives). Despair that I’ll never get “better” (what’s recovery mean, anyway?). Worry about the impact on my friends (no one wants to be a Burden) and family (some of my struggles have genetic factors). Shame about how much it interferes with my productivity (after all, I am a civil servant – perhaps someone less-afflicted would make more efficient use of the public’s resources?).

Those are the negative emotions – there’s also a positive side to my emotional landscape. Gratitude that my illness is manageable at all (I’m still here!), because I’m well aware that I occupy a comfortable seat on the struggle bus – easily business class or better. Joy in the work and accomplishments I have taken part in, despite the obstacles. Equanimity. Purpose. And, increasingly, service: having my own struggles puts me in a better position to help others identify and navigate their own – people who haven’t (yet) had major illness just can’t even.

There are many reasons motivating this disclosure.

I want to chronicle my experiences and consolidate the rationales I have developed as a guide for myself while I continue to muddle through. When I’m doing well, I can see ways that experience with illness can benefit both self and others. But when I’m ill, it is hard to see past my “failings”. Perhaps if I can see how far I’ve come through these treacherous waters I’ll be better prepared to navigate what comes my way in the future.

I want to connect with others to build community; the handful of interactions I’ve had with folks that share some of my experiences have affected me profoundly and benefitted me tremendously.

I want to share my lived experiences with my colleagues so I can offer some explanation (but not excuse) for various ways I (perceive to) have “dropped the ball” over the years – on papers, proposals, projects, and other plans.

I want to provide fair warning to colleagues and potential collaborators / mentees: my ambition frequently exceeds my capacity, and I can become very ill very quickly with little advance notice. Although I endeavor to minimize the impact of my limitations and compensate for the costs incurred, I want to provide information I view as important for others to decide whether and how to interact with me.

But most importantly, I regard it as critical that we do any and all work we can to de-stigmatize health struggles – particularly mental illness, since many/most of us have internalized biases against its legitimacy. Beyond discussing and validating the (very real, very heavy) suffering that’s entailed, I want to call attention to the fact that this shit can kill you. As foreshadowed by the profanity and link in the previous sentence, this article is going to be quite “raw”. Consider this a trigger warning for self-harm & suicidal ideation et al.

This got long – there’s no shame in skipping to tl;dr

- thanks

- childhood

- symptoms, pt. 1 – “physical” health

- an aside

- diagnosis & treatment

- prognosis

- symptoms, pt. 2 – “mental” health

- diagnosis & treatment

- prognosis

- symptoms, pt. 3 – “mental” health, pt. 2

- sabbatical

- diagnosis & treatment

- my period

- prognosis

- you are not alone

- PS: on disclosure

- tl;dr

thanks

Before going any further, I want to express my deepest gratitude to colleagues who have disclosed their own struggles with illness, whether privately to me or publicly to our community. Both actions are incredibly courageous (as I discuss in more detail below, one cannot know with certainty that private disclosures won’t ever be made public).

Of course I cannot publicly call out individuals in the former group, but they know who they are, so I can speak directly to them: I am so happy to have you in my life as a colleague and friend; you have given me a precious gift I will always cherish; I celebrate every day that we persist – we are still here!

The folks in the latter group are few and far between – I have been particularly inspired by the trailblazing advocacy and scholarship of Kay Jamison, Susan Wendell, Jen Mankoff, Elyn Saks, and Alicia Andrzejewski.

childhood

I have Adverse Childhood Experiences and genetic factors that pre-dispose me to a constellation of debilitating illnesses and disorders. To put it succinctly: I was emotionally abused by one of my parents (diligent readers of my blog can infer their gender identity) and most people in my family (immediate and extended) have or had untreated substance use disorders, which illness has killed too many of them.

The trauma I endured as a child instilled in me a deep and abiding self-hatred. I thought I deserved the mistreatment I experienced. We’re told that parents love unconditionally – how much of a monster must I be to have that supposedly universal privilege denied me? I concluded that there must be something deeply flawed and unwanted inside me.

I’ve experienced intense suicidal ideation as long as I can remember. When my mood is low, I ruminate on being unalive, on wanting to stop existing. I grew up thinking this was “normal” – that everyone retreats to this deep dark place from time to time. As an adult, I now recognize these thoughts as alarming symptoms of underlying illness (and, in such a young child, suggestive of abuse or trauma).

There were also telltale signs of anxiety: bedwetting; physical tics that others notice (and mock); extreme distress at perceived failures or mistakes; aversion to social or group activities; head- and stomach-aches.

To confirm / clarify, I’m not sharing all this crap to elicit pity or darken your day. My negative experiences were more than compensated by other people in my life who did (and do) love me unconditionally. But I think it’s tempting to ignore these early experiences or downplay their influence in adult life, despite ample evidence to the contrary.

symptoms, pt. 1 – “physical” health

I first started experiencing (what I now recognize as) intermittently-disabling illness early in grad school (only recently have I begun to view my experiences through the lens of capital-D Disability). By my second year as a PhD student, I found myself with debilitating pain in my arms, neck, and shoulders. I was able to use a computer for 30 minutes a day – max – for months. Each day would end with painful muscle spasms. The consequences for my personal and professional life were profound.

It’s worth dwelling on the consequences for a sec.

Computer use is central to academic work. In particular, I use computers to collect and analyze data, write code, write papers, report to sponsors, present to colleagues, and communicate with you, dear reader. So I seriously considered the prospect of dropping out of grad school – whether by choice or due to lack of progress through the program.

Beyond computer use, there was a constellation of other activities that “aggravated my symptoms” (by which I mean “caused me debilitating pain”) running the gamut from exercise (I had to give up yoga and rock climbing) to travel (not being able to move or stretch for long periods, lifting / carrying bags) and countless mundane, routine, everyday things I took for granted before this illness (literally sitting! it was excrutiating to attend classes, seminars, conferences, meetings, etc).

Sometime in the middle of this, I herniated my L2 disc (pro tip: if you’re trying to move a rug under a heavy piece of furniture, move the furniture first …). In addition to introducing a new source of chronic and intermittently-disabling pain, the injury partially de-enervated my right leg, causing numbness in my gastroc and loss of muscle mass in my quad. I remained ambulatory, but with even more limitations on my movement.

an aside

At this point in my narrative, I’m imagining some readers thinking I’m exaggerating symptoms or seeking attention or rationalizing laziness or making a bigger deal out of all of this than my circumstances justified. After all, everyone has obstacles to overcome – many much more significant than mine. I’m not special, other than the obvious privilege and narcissism that motivates me to blast this story on the interwebs. This is probably, mostly, just me projecting my own insecurities. But if you happen to find yourself thinking any of these things (even dimly), you are in good company: I think them all day, every day.

diagnosis & treatment

Initially, I thought I was experiencing temporary impairments due to chronic overuse, so I tried improving my computer ergonomics (I still use the keyboard and mouse), taking over-the-counter painkillers daily (not a great idea, as it turns out), mineral baths, regular breaks, stretches, low-impact exercise, deep breathing, mindfullness, etc. Each self-prescribed intervention offered some limited relief, but nothing came remotely close to a “cure”.

Eventually I worked up the courage to seek professional care, so I marched down to the Tang Center. A doctor referred me to physical therapy, where I had the pleasure of working with a wonderful PT – one of two medical providers whose contributions to my graduate school experience warranted an acknowledgement in my thesis.

Physical therapy helped but did not “cure” my symptoms, so after exhausting my insurance’s generous (lol) allotment of sessions, I took my PT’s advice and tried acupuncture (turns out there’s reasonably good evidence supporting efficacy of acupuncture for chronic pain, though I wasn’t aware of this at the time). This also helped, for reasons that remain mysterious (not only to me), earning the second acknowledgement in my thesis to a medical provider.

prognosis

After years of PT & acupuncture I saw a neurologist and got a second opinion from another GP outside the University Health System, both of whom offered the very helpful observation that I will generously paraphrase as “you are too young to be having these problems”.

So I resigned myself to living with the impairments. I accepted that I had to respect a laundry list of hard constraints: limit computer use; don’t sit too long; don’t stand too long; do daily PT exercises; but don’t exercise too much; … Not ideal, but life could certainly be wayy worse.

symptoms, pt. 2 – “mental” health

I first realized there was a real problem with my brain when I started getting panic attacks. If you’ve never had the experience of losing control of your body, feeling like your insides are bursting out while your outsides are crushing in, sweating, panting, head spinning, stomach churning, wanting / needing / begging for any way to make it stop: bless your heart.

The panic set in at the end of my first year as an Asst Prof, a few weeks before the Fall quarter began. I was familiar with anxiety – I’ve had a potpourri of textbook symptoms tracing all the way back to some of my earliest childhood memories. But this was different. Unbearable. Terrifying. Existentially dreadful. Bless my heart.

The scariest thing was imagining what it would be like to be back on campus, performing: in the classroom, in faculty meetings, in group meetings, to students and colleagues and collaborators and mentees and Program Managers and …

diagnosis & treatment

Not having significant internalized stigma against evidence-based treatments helped me, at the mild urging of my wonderfully supportive partner, to seek help from multiple providers. My GP recognized symptoms of depression lurking underneath the panic and prescribed bupropion (which, incidentally, is a medication worth considering by all Seattleites and possibly everyone residing in northerly latitudes). The therapist I found through a decidedly un-systematic search who (a) was covered by my insurance and (b) worked in my n’hood started meeting with me weekly and referred me to a most excellent psychiatrist satisfying the same constraints (a,b), which psych added fluoxetine into the mix, since it has excellent anti-anxiety properties in addition to being a frontline anti-depressant.

You know what’s funny? After about 6 weeks, my chronic muscoloskeletal pain just, sort of, stopped (really: diminished greatly). And hasn’t come back (at least, not to the level it’d been at for years) in the intervening 6.5 years I’ve stayed on the prozac. Soo .. the simplest explanation is that … it was all in my head? In, like, a very real material sense ..

(^^^ sorry, I haven’t figured out how to get Unicode working >.< lol )

prognosis

At this point in the narrative it seems like I’m dealing primarily with anxiety and depression – the earlier chronic pain largely being a manifestation of the former. I’m pursuing the best evidence-based treatments available to me (psychotherapy + psychopharmaceuticals), trying to make the recommended lifestyle changes, and all of this effort seems to be working – I kinda feel like I’m getting better. (Maybe?)

But I never really recover.

Not fully, or even satisfactorily.

Depression and anxiety come and go, sometimes in tandem with external stressors (of which there are no shortage in my line of work), sometimes seemingly out of nowhere. I stay on the meds, accepting that I’ll take them the rest of my life. I intermittently abstain from recreational depressants – sober when I’m low, inbibing when I’m feeling good. None of these outcomes are entirely surprising, given the stats on recurrence and relapse. Nevertheless, it’s distressing – particularly since mild-to-intense suicidal ideation has always come part-and-parcel with low mood for me.

This goes on for a while. The rest of my time on the tenure track, actually. In fact, the depressions seem to be getting worse (at the very least: no better) and coming more often. Even when I’m feeling good, I don’t feel as good as I used to (I think?). Maybe it’s just that I’m getting old(er). Or maybe I need to try harder – maybe it’s a moral failing? I’ve gained about 10 pounds a year since my kid was born – maybe it’s because I’m fat(ter)? But it’s hard to eat less and exercise more when I’m depressed … and anyway, dwelling on body shame isn’t going to improve my mood.

This confusing milieu of thoughts epitomizes my experience with chronic illness – I find it hard to separate the mundane ups-and-downs and aches-and-pains of normal life from illness that needs treatment. Most or all of the symptoms sound familiar to any “healthy” person. But when I take a step back and look at the totality of my experiences, something seems “off” …

symptoms, pt. 3 – “mental” health, pt. 2

The last six months before I started sabbatical were rough.

My chair told me in early 2022 that my tenure case was approved. Despite the wonderful news, I spent that month in one of my worst depressions yet. I wasn’t completely catatonic (I’d had the privilege of that special symptom during an episode a few years prior), but I had intense SI. It was the first time I started actively thinking through how to kms. Dissociating, I’d observe myself applying my engineer’s brain to the task – in particular, the logistics of how I’ll do it and what affairs I need to get in order beforehand.

Scary shit.

That episode lifted, or at least lessened, for a couple months – though I continued experiencing ups-and-downs, with the average much lower than I’d like.

Another scary depressive episode emerged at the end of the academic year, despite the fact that I was just weeks away from 18 months of summer. Again I was ruminating on my death, achieved actively or passively.

sabbatical

I left Seattle and WA state with my partner and kiddo at the end of summer to start 9 months of sabbatical leave in a very special place that would probably be better off without me.

This major life transition came with a number of benefits and costs.

On the plus side, I had the privilege of leaving many responsibilities behind, enjoying copious free time, and experiencing much more stable zeitgebers than the life of an academic on the quarter system in the PNW affords.

On the minus side, I lost access to my therapist and psychiatrist, as they are only licensed to practice medicine in the state of Washington. And despite how it may superficially appear, sabbatical is not vacation – it’s life, only harder, as you start over learning to live in a new place in the absence of support structures and a familiar environment.

External circumstances certainly influence my mood, but the big swings seemed to just sort of happen. This phenomenon was confounded pre-sabbatical by the many interacting rhythms of my life: seasons, deadlines, holidays, that damn academic quarter system. But in the absence of these external factors, the cycles persisted and became blindingly salient and unmistakable.

diagnosis & treatment

Turns out I’m (type 2) bipolar. (Probably.)

This “working diagnosis” emerged in meetings with my new HI provider, as the cycling I’d been experiencing for years between (sometimes extremely) high-functioning periods punctuated by (often desperately) depressed episodes is just not how (unipolar) depression works. Especially given the rapidity of my cycles – I’d swing between extremes 4 or more times each year.

Most folks don’t know much about bipolar disorder (BD), so a couple quick notes about the history and characteristics are in order:

- BD is a mood disorder, putting it in the same diagnostic category as (unipolar) depression (and making it sound delightfully light and easy to fix :D );

- DSM-III replaced the term “manic depression” with “bipolar disorder” in 1980 – they’re essentially the same thing, but the latter was viewed as less stigmatizing;

- DSM-IV distinguished between type-I and type-II bipolar disorder in 1994, with the key difference being the occurrence of (even one) episode of mania – BD-I if you’ve ever been manic, BD-II if you’ve only ever been hypomanic (i.e. “not quite” manic);

- the term hypomania describes a state of “elevated” mood and/or energy and/or productivity and/or confidence and/or sexuality and/or creativity and/or …

It can be really hard to diagnose bipolar disorder if the (hypo)manic episodes aren’t impairing or distressing. And in the case of type-II, they frequently aren’t.

Speaking for myself, my hypomania manifests as an unrelenting drive to get shit done. I’ll levitate out of bed in the morning – sometimes an hour or two early – and get to it: wake up my kid, make breakfast, pack lunches, drop kid off at school, work work work through back to back to back meetings, exercise, make dinner, clean up, put the kid to bed, then do a home project and/or work work work some more until I put my head on the pillow. If this sounds kinda nice actually: I agree!

So I’ve tried to extend hypomania as long as possible. However, what goes up must come down. And in my case, there’s a remarkably predictable pattern to these cycles.

my period

Early in my sabbatical, I started tracking my mood, sleep, and a few other clinically-important variables every day using a chart I found in the (very helpful) Bipolar II Disorder Workbook known as the NIMH-LCM. By the time I returned to Seattle and met with the psychiatrist I’d been seeing for years, I had many months of data to report.

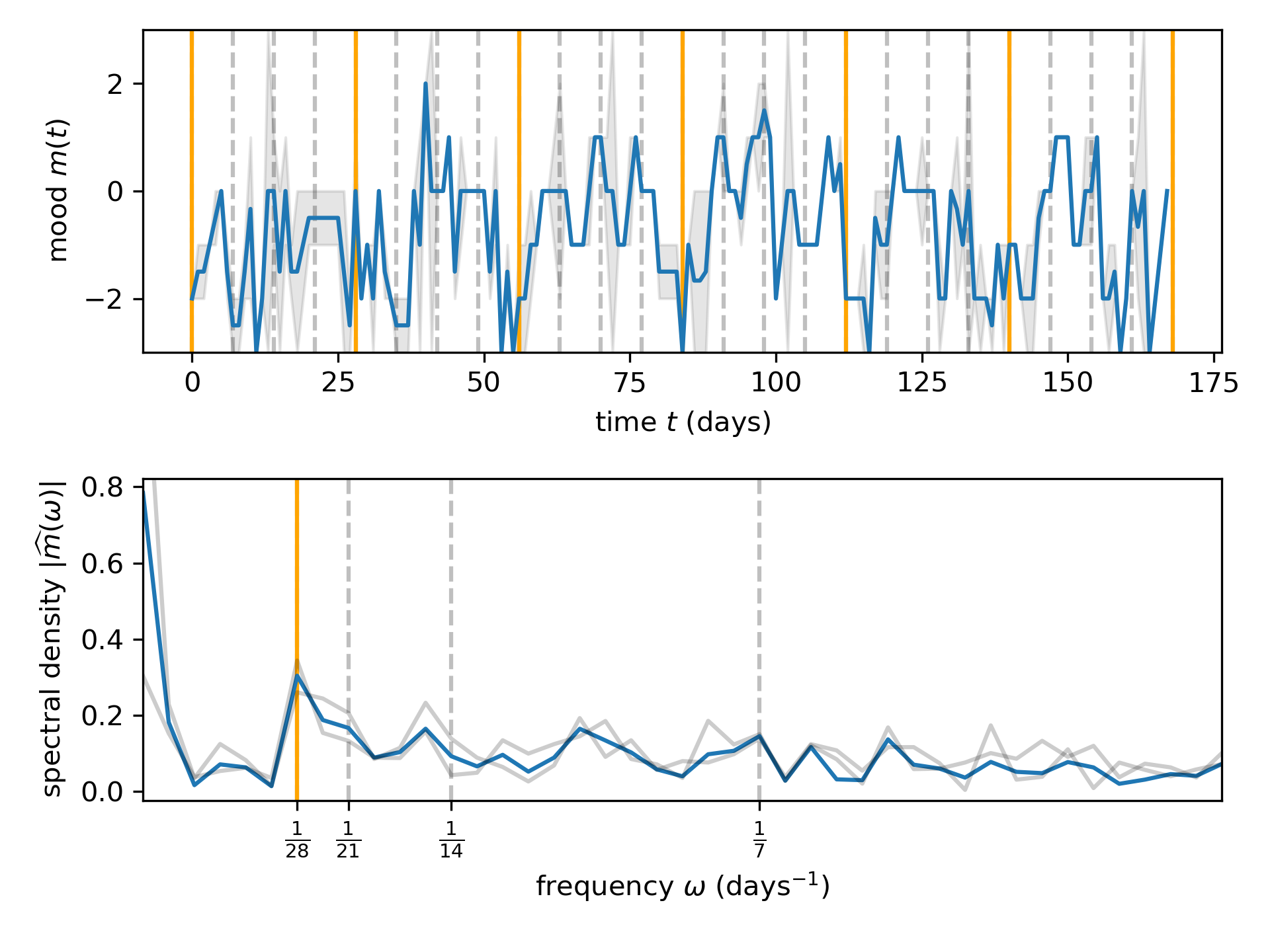

My doc used the chart in combination with my family history (I have a second-degree relative who was diagnosed with BD-I) and self-reported experience to arrive at my formal diagnosis. But once that was established, they mentioned offhand that they’d be interested in running a “periodogram” on my data. Of course I couldn’t help but look up what that means, and of course it’s just the power spectral density. So I crunched the numbers – here’s what the last 6 months of data from my sabbatical look like:

What do you see, dear reader?

I see a peak at 28 days, which is .. strange for a person that does not menstruate. Perhaps I’m a lunatic? Beyond the mystery, this result has started to help me and my loved ones predict when my illness may become impairing. And it helps to convince me that there’s something happening inside my body+brain that is not under my control.

Allow me to describe a typical month during this time period.

At the outset, I’ll start to feel good. Not “great”, not too good, but just: fine. I’ll get shit done, but it won’t feel like there’s a runaway locomotive pushing me driving me in a way that I can’t stop or slow down. I’ll just look at a chore in my life or a task in my work and think “sure, no problem” – and I’ll do it and move onto the next job. I’ll attend to my relationships, engaging with my kid and my SO, answering phone calls and text messages from friends and family. I’ll make plans for the future – vacations, house projects, ambitions for my professional or personal life – and feel confident about my ability to complete them.

Then one day, out of the blue, after 2–3 weeks, my mood and energy will drop of a cliff. Sometimes it’s bearable – it just feels like I have the flu and I’m uncharacteristically cranky. Other times it’s .. bad. I’ll talk and move slowly, like I’m in a tank of molasses. I’ll have poor memory, it will be hard to remember words. I’ll crave sugar. I’ll tear up and cry – sob – for seemingly no reason. I’ll stop responding to email, text messages, phone calls. I’ll feel overwhelmed by the future. I’ll hate my self and everything around me. And I’ll want to die. More than anything. I’ll fantastize about how it could happen, and about what the consequences would be. I’ll do anything I can to distract myself from these thoughts.

And then after a week or so, I’ll “switch” back to “normal”, and start the cycle over again …

This pattern repeated consistently for the first half of this year – that’s what the peak on the spectral density at 1/28 Hz represents: the most desparately painful cycle I can imagine.

prognosis

This brings us to the present.

I’m still learning what it means to live with bipolar disorder. The stats are scary: up to 1 in 5 people with BDII die from it. A couple of times I’ve shared my condition and that stat, people have responded with something along the lines of “well, the good news is you’re not at risk of dying from it”, citing my strong support network, excellent healthcare providers, personal commitment to treatment, the fact that I’ve maintained relationships and a career despite being untreated, etc. And I agree – I have a lot working in my favor.

But for the record: I’m genuinely terrified of dying from this illness. When I’m unwell, it feels like some of the factors that generally work in my favor could actually make my depressions more dangerous. For instance, having a strong network of wonderful relationships brings a heaviness to my life that feels unbearable when I’m low, as I’m overwhelmed by shame and self-loathing about how many people I’m “letting down” with my illness. And regarding my ability to “get shit done” – I’ll let you connect the dots.

I’m trying to get a handle on the illness. I’ve been on the wrong meds for years, as antidepressants may destablize mood in the bipolar brain. The first mood stabilizer I tried didn’t seem to help (?) and came with cognitive side effects that are mild but nevertheless worrying for an academic. The latest news is that I’ve switched to the heavy-hitter. But I’m still cycling.

I’m worried about the upcoming academic year. So, with the support of my provider, I’ve requested disability accommodations through my university’s Disability Services Office and discussed these accomodations with my College’s HR and my Department’s Chair. So far everyone has been wonderfully supportive, which puts me in yet another privileged class – I have heard absolute horror stories from other faculty in my university. I am grateful for the support I have received, as it greatly reduces the anxiety I feel about the prospect of reliably serving as a teacher and colleague.

you are not alone

As a kind of conclusion, I want to say to anyone with any kind of illness: I am so, so sorry you are going through this; and you are not alone. I am here for you as a resource and advocate. You are welcome to contact me at any time: sburden@uw.edu.

PS: on disclosure

There’s an interesting “game” that the chronically ill and/or disabled play with disclosure in their professional spheres.

On the one hand, choosing not to disclose limits our access to accommodations that could level the playing field as we work with and perhaps compete against our healthy non-disabled colleagues. Of course this effectively puts the burden of access entirely on us, even though we believe that disability resides without, not within.

On the other hand, disclosing and requesting accommodations from one’s employer and colleagues can have enormous costs – both internal and external.

For instance, someone (like me) may feel intense shame about their circumstances. Of course this is something the individual can (and I do) work to free themselves from (e.g. through group and individual therapy). But it can nevertheless be extremely taxing and, therefore, make avoiding disclosure altogether an extremely appealing option.

Externally, there are no shortage of stigmas and irrational beliefs programmed into each of us since birth about illness and disability. Who among us (other than perhaps those who have had extensive experience with disability) does not reflexively associate disability with deficiency – moral, physical, and/or cognitive? Who doesn’t pity the ill and feel gratitude for one’s health? Exposing oneself to the constant judgement, othering, pity masquerading as sympathy, and awkwardness is a major disincentive to disclosure.

But that’s all “just” subjective – the opinions of self and other. What about economic consequences and opportunity costs?

Speaking specifically to the academic sphere: will disclosure affect evaluations for promotion and/or tenure? Will it make program managers less likely to fund me? Will I get invited to give talks or collaborate on projects less often? Will prospective students and postdocs choose other advisors? Will I be sidled with extra (often hidden and unrecognized) service in my Department / College / University / professional society / academic community? Will colleagues question my fitness to do this job? Will they regret hiring me in the first place? I’m a worrier – I could go on.

It’s also important to recognize that, to whatever extent the stigmas and concerns described above are real, selective disclosure gives others power over you. Let me explain. Suppose I disclose to my HR department and request a corresponding accommodation. In the implementation of the accommodation, at least one of my colleagues will be made aware of the fact that an accommodation is needed. Although it is illegal in the US for that person to disclose to anyone else (other than those strictly necessary to implement the accommodation), and even more illegal (is that a thing? IANAL) to discriminate against me because of my request for accommodations, it is entirely within that person’s power to do either. And if they’re careful, they will be practically immune to consequences: all it takes to spread information is a few words spoken in private; and discrimination can manifest in myriad subtle ways.

So the fourth reason I am choosing to disclose now in this very public way is that I do not want to grant others power over me. This is my body, these are my circumstances, and I choose to live with them.

Also putting all my cards on the table in this way means (the) “they” really can’t fire me for my illness :)

tl;dr

Turns out I’m bipolar.