Dr. Honey on News Beat Podcast, "MLK's Last Month: Memphis"

Dr. Michael Honey on the News Beat podcast, discussing Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s last month in Memphis.

Episode Description

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. demanded justice and equality—two essential truths which still have not been achieved, more than 50 years since his murder on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. Year after year, without fail, politicians, pundits, and corporations bastardize his image and legacy to their own capitalistic agendas—capitalism and its many evils something MLK fought so relentlessly against.

This year, along with our annual re-release of our inaugural episode ‘MLK: What They Won’t Teach in School,’ we’re dropping this brand new one highlighting his last month and final campaign, supporting the Memphis sanitation strike.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was sooo much more than what talking heads and (collective groan) car companies purport. Do not confine him to those infamous four syllables, ‘I have a dream.’ Hopefully, these two episodes will help you understand why.

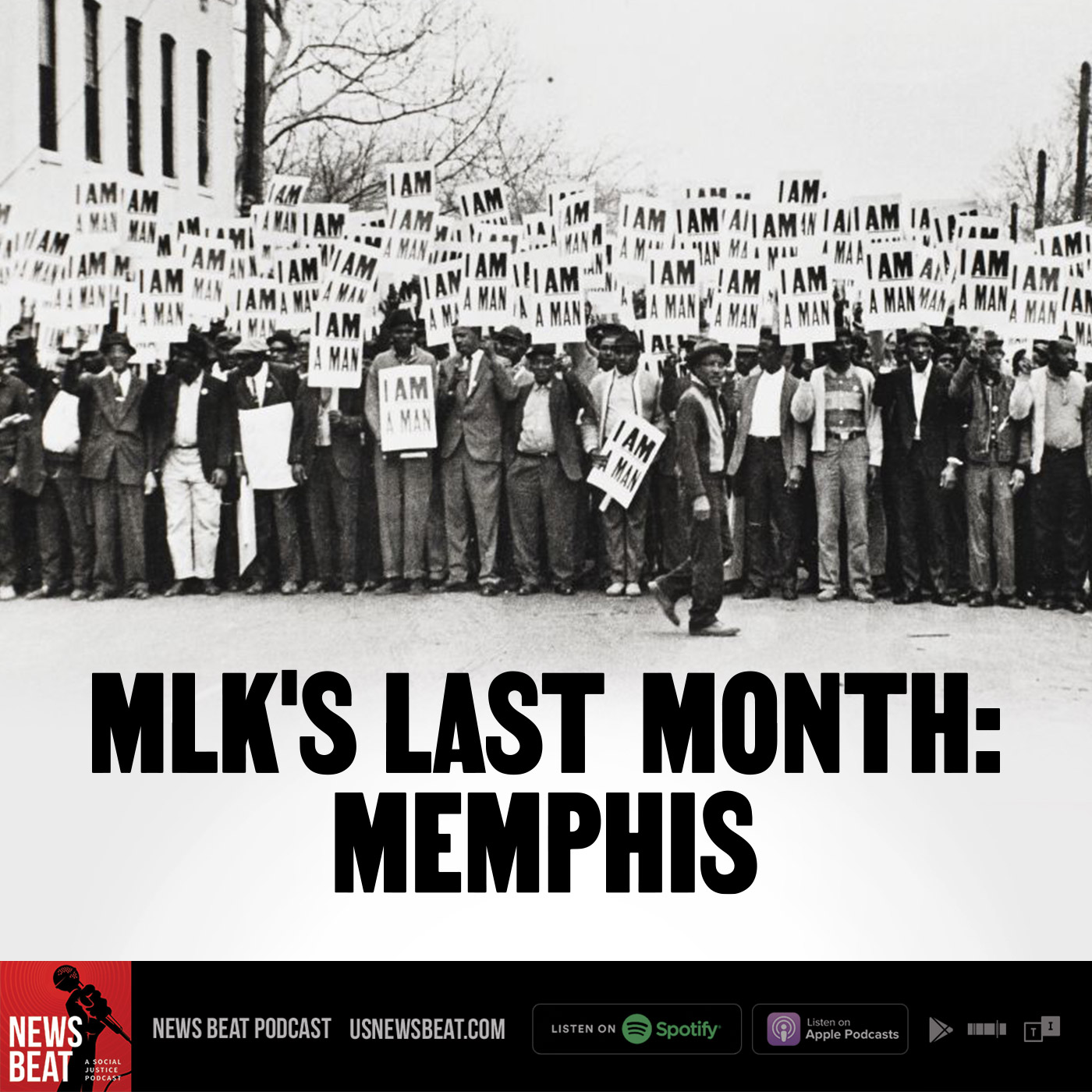

Photo credit for art: Ernest Withers, St Lawrence University Art Gallery

Click the links below to listen on either Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

---

Highlights:

(5:56)

"What he said was, in order for us to do anything about our condition, we have to be able to vote, we have to have rights in the court, we have to have equality at the political and legal level. But that doesn't solve our problem. Our problem essentially goes back to the history of slavery and unpaid labor in America. And his great- great- great-grandfather was a slave. So, he grew up in Atlanta with his father coming out of sharecropping in the countryside. All around him in the neighborhood he lived were plenty of very poor people. He always had, what he called, a 'kinship with the poor'. The media portrayed him at the time as a 'civil rights leader'. But he said, if people think that's what I am, they don't understand what I'm doing. The Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act was stage one of the freedom struggle. Stage two is to get some economic justice for Black people in America, but also for Native Americans, poor whites, Puerto Ricans, down the list of people who are dispossessed. When he came to Memphis in 1968, there was a huge list of dispossessed people in the United States. He told the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1966 we've got to begin to ask questions about the whole society, 'we're called upon to help the discouraged beggars in life's marketplace. But one day we must come to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.' A year later, he said something is wrong with capitalism as it now exists in the United States. A radical redistribution of power must take place."

(8:39)

"And so when he came to Memphis to speak on March 18, 1968, he was organizing what he called the Poor People's Campaign. And his idea with that was to put into Congress an Economic Bill of Rights for the disadvantaged, and also to stop the Vietnam War. He saw the Vietnam War as one of the essential problems in trying to solve poverty in America. The United States was spending it's energy and money on war against poor people in a peasant country, people of color, Vietnamese and Cambodians. And he saw it as a racist war, and also a war against the poor, and he said we should recognize it as such."

(10:26)

"The Memphis story is just as important as the Montgomery Bus Boycott story. 80% of the people living there were poor people. Who's riding the busses? Maids, service workers, janitors. These were the people that King really related to, the working poor. And that launched his leadership role, but this was something he was always concerned about as a minister."

(14:19)

"The [the striking workers in Memphis] were having trouble developing unity. King's specialty was unifying people into coalitions. In Memphis, for example, these Black workers who were on strike, 1300 of them, had been organizing for year. They didn't make enough money to live on, they had to get help from churches and anti-poverty funds, they didn't have work clothes, they didn't have any set hours. (...) There was an incident that occurred in early February where two Black workers were killed. That set off the strike. This is a story for our own times in many ways. The people trying to organize in the warehouses, in retail, and other low wage jobs in the United States have a similar problem of not being recognized and not having the dignity of being able to have the dignity to represent themselves."

(17:01)

If the teachers stopped working, if the students walked out of school, if all of the workers walked out, Memphis would stop. Because in fact, Black people did most of the work, most of the menial serve work, in Memphis. So he proposed a general strike of labor, of Black labor, and also invited the other unions to support that.

(19:12)

"But it was kind of a minor thing compared to the urban uprisings that we saw all through the '60s, like Detroit '67. But the police saw it as a great opportunity and they waited and started beating the hell out of everybody. And then they went even beyond the march and started going into cafes, pulling Black people out of cafes beating them up. They went into a poor people's housing area and murdered a Black teenager who had his hands in the air. It became horrible. So everybody accused King of being the one who caused it."

(21:23)

"Of course this is the worst thing he could ever imagine; leading a march that turned into this, and people even being killed. So then he had to come back. That's what he was doing in Memphis on April 3rd, giving his To The Mountaintop speech, his last prophetic where he basically almost said he was going to be murdered. He seemed to have a premonition of what was going to happen."

(23:36)

"And the next day, he was assassinated. Remember, they did win the strike in the end. We lost King, but they won the strike."