Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Tibetan Language Erasure | References

A key feature of cultures word-wide is their ability to relay information and intergenerational knowledge through a shared common language. Not only then is the language a core identity of a culture, but it becomes attached to all elements of a people as their vocabulary shapes the way that they interact with the surrounding world and others. In models of colonialism, language is often the first and most noticeable distinction between peoples, which is why it is often the first portion of a culture that is directly targeted. Language activism is a centuries-long tradition by Indigenous peoples, tied to protecting their identities, and is still present across hundreds of international movements.

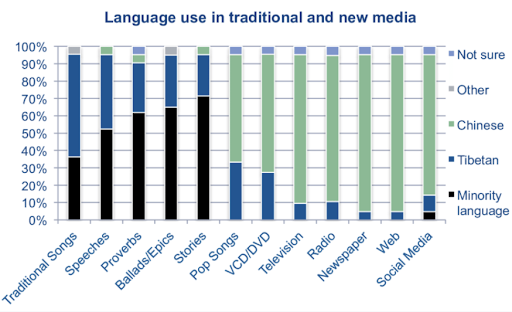

Language erasure is not only an institution of colonialism centered around dehumanizing a culture, it is additionally a deeply political process that is centered around the control of power. Following the occupation of Tibet by the Communist Chinese government in 1950, multiple policies and orders across the newly conquered state were enacted that actively discouraged the use of the Tibetan language. These laws were often indirect and subtly worded however their intended effect was wide-spread and difficult to reverse. The Chinese government used a diverse array of methods to limit the use of Tibetan, including exchanging Tibetan school books for ones provided by the government written in Chinese, changing all street signs and official documents to be only written in Chinese, prohibiting Tibetan from being used in official proceeding, and spreading a propaganda campaign that called Chinese the language of the future. It was not until the 1990’s that Tibetan activists became outspoken on the issue of language activism as it became apparent that the generation raised after Chinese occupation was more comfortable speaking Chinese than their own native language. However, as Tibetan awareness grew, the Chinese government began actively jailing and oppressing activists that sought to mobilize the populous. Even in the 21st Century little change has been realistically achieved by Tibetan demonstrations and several key leaders of the movement are currently imprisoned in China for actions taken against the authoritarian regime.

Tame Wairere Iti has experienced restrictions of his own language and been involved in language activism since he was in primary school. Iti believed that the language was a part of being Maori and didn’t understand how a person could be one without the other. The principal of his school declared that no one was allowed to speak Maori and were to only use English. Tame and his close friends chose to stand up to his principal and continued to speak Maori in school for weeks even though he was punished for standing up for his culture. From a young age, Tame has clearly understood the connection between both culture and identity with language and the importance of keeping native languages alive. For these reasons, Tame Iti would side with the Indigenous peoples of Tibet and help them attain the freedom to speak whatever language through the implementation of his unique and effective activism strategies.

Tame Wairere Iti has consistently been involved in activism for the Maori language since his youth and would undoubtedly have a strong opinion on language politics. Tame Iti sees language as an extension of self that deserves to be protected and celebrated like any other aspect of one’s culture. Although Tame Iti carries a positive view of China and Communism, as he had previously traveled there during the 1973 Cultural Revolution, he is outspoken on the topic of equal and accessible Indigenous rights to speaking a native tongue. Tame Iti would likely respond to this event by encouraging people to speak and use Tibetan whenever they could in their daily lives, as well as help to set up large scale protests. Although New Zealand’s relationship with the Indigenous Maori has been historically very different from China with Tibet, there are enough similarities that Tame Iti would likely continue to advocate in a similar manner. Tame Iti has additionally shown that he is not opposed to using force to effectively execute his plans, and thereby deliver a strong and cohesive message. However, as of now, Tame Iti has primarily retreated from the public sphere, due to his multiple arrests in the early 2000s, and is now focusing more on activism through art. It is important to note that Tame Iti would likely not want to get heavily invested in this struggle as he has repeatedly stated that while he supports other Indigenous groups, he believes that, when they can, they need to find their own path to recognition. It is for all of these reasons that Tame Iti would both fully support and recognize the Indigenous Tibetan’s continuous struggle for language recognition.

Not only is the study of the relationship between identity, language, and culture deeply personal for many individuals, it requires a reexamination of ideas of progress and prosperity. Both Tibetan and Maori activists grapple with countries that see their languages as obsolete, and with being the minority population in a land that once solely belonged to them. Tame Iti has advocated since his youth for both language recognition and Pan-Indigenous unity which is why he would undoubtedly support Tibetan resistance against Chinese policies.