Selected photographs from

The Southern

Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed

America

|

A southern family arriving in Chicago during World War I. (Chicago

Commission on Race Relations, The Negro in Chicago [Chicago, 1922]) |

Coming to work at River Rouge. Among the 96,000 employees at Henry Ford’s

Detroit plant by 1944 were 15,000 blacks and at least as many white

southerners. (Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University) |

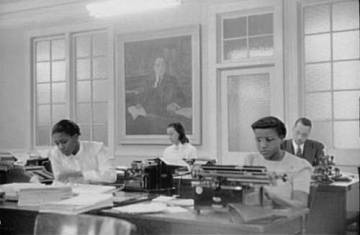

In 1940 when this picture was taken, blacks were excluded from most

clerical, sales, and white collar jobs. Firms that served the black

community, such as this Chicago-based insurance company, provided a handful

of opportunities for well educated migrants to use their skills. (Library of

Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection) |

Henry Ford’s massive Willow Run B-24 bomber plant at Ypsilanti, Michigan,

hired thousands of southern migrants during World War II, mostly whites.

Ford had taken the lead in hiring black workers in the 1910s and 1920s, but

changed course in the early 1940s after black workers joined the United Auto

Workers union. (Walter

P. Reuther Library,

Wayne State University ) |

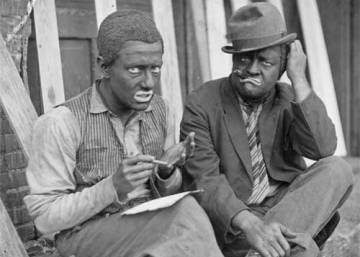

Posing in blackface for a Chicago Daily News feature in 1929, Freeman

Gosden (a white migrant from Virginia left) and Richard Correll

were the voices behind Amos ‘n’ Andy, the most popular program on

radio. The nightly radio skits helped change understandings of American

racial geography while disseminating powerful images of black southerners in

the big cities of the North. (Chicago Historical Society) |

The most

popular show on television in the early 1960s, The Beverly Hillbillies

continued the tradition of hillbilly representations that had influenced

southern white identities since the 1920s. |

Boxing great Joe Louis with John Roxborough, the attorney/policy

king/businessman who, with his partner Julian Black, managed the fighter’s

career. Twelve years old when his family moved to Detroit from rural

Alabama, Louis broke boxing's color line using the institutional resources

of the Black Metropolis. (Walter

P. Reuther Library,,

Wayne State University) |

Part of black Chicago’s large entertainment zone, this cabaret catered to

well-heeled audiences, mostly whites on this evening in 1941. More than

1,000 musicians, actors, and dancers worked in Bronzeville's entertainment

sector. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI

Collection) |

Selling the Chicago Defender, 1942. Newspapers keyed the new cultural

apparatus that southern migrants built in the great cities of the North.

(Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection) |

Lorretta

Lynn’s country music career began not in Kentucky but in northern Washington

State. Winner of 17 blue ribbons for canning at the Northwest Washington

State fair she poses for this 1958 newspaper photo. That was also the year

that she joined a local band and began singing in local clubs. (Bellingham

Herald) |

Warren, Michigan, 1956. This Detroit suburb and other suburbs across the

North and West were favored residential choices for white southern migrants.

(Walter P.

Reuther Library,, Wayne

State University) |

Reverend C.L. Franklin turned New Bethel Baptist into one of the largest and

most politically active black churches in Detroit. Father of Aretha

Franklin, C.L. grew up in rural Mississippi and held his first pastorate in

Memphis. The family moved to Detroit in 1944. (Walter

P. Reuther Library,

Wayne State University) |

Elder Lucy

Smith (here in 1941) led All Nations Pentecostal Church, Chicago’s largest

Pentecostal assembly. The dynamic faith healer migrated from Georgia in

1910. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI

Collection) |

Reverend J. Frank Norris turned Detroit’s Temple Baptist into a bastion of

rightwing fundamentalism. Norris (right) joins Michigan Governor

Luren Dickinson, a prohibitionist, at a 1940 campaign rally. Norris commuted

between his churches in Detroit and Ft. Worth from 1935 to 1950. (Walter

P. Reuther Library,

Wayne State University) |

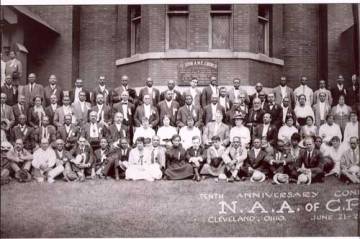

Some of the delegates to the 1919 convention of the NAACP held in Cleveland.

The bi-racial organization was an example of the new political alliances

that became possible in the Black Metropolises of the North. (Emma and Lloyd

Lewis Family Papers [LF neg. 14B] Special Collections Library. University of

Illinois at Chicago) |

Picketers

in front of a Seattle grocery store, 1947. Supported by CIO unions, church

groups, Jewish organizations, and the Communist Party, black activists

forced most stores and restaurants to end “white only” service policies in

that city by the end of the 1940s. In 1949, the same coalition secured a

Fair Employment Practices Act for Washington State. (Museum of History and

Industry, Seattle, #13693) |

Detroit detectives show off confiscated robes, masks, and weapons belonging

to the Black Legion. Before the Klan-linked organization was broken up in

1936, members had committed a string of murders and assaults in Ohio,

Indiana, and Michigan. Newspaper reports claimed that most of the members

were former southerners. (Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University) |

George Wallace enjoyed considerable support in the white suburbs and smaller

cities of Michigan. Note the “Vote for Wallace” t-shirt at this 1971

anti-busing demonstration in Pontiac Michigan. (Walter

P. Reuther Library,

Wayne State University) |

Former Texan Jesse Unruh (left) was Speaker of the California State Assembly

when this photo was taken in 1966. With him is Robert Moretti (born in

Detroit) who would become Speaker in 1971, and fellow Texan Willie Brown ,

Speaker from 1980 to 1995. (James D. Richardson papers, Department of

Special Collections and University Archives, The Library, California State

University, Sacramento) |

|