Translation

I love doing research on interfaces. There’s nothing like imagining an entirely new way of interacting with a computer, creating it, and then showing it to the world. But if the inventions that researchers like myself create never impact the interfaces we all use every day, what’s the point? The answer, of course, is more complex than just a binary notion of an invention’s impact.

First, much of what you’ve read about in this book has already impacted other researchers. This type of academic impact is critical: it shapes what other inventors think is possible, provides them with new ideas to pursue, and can sometimes catalyze entirely new genres. Think back, for example, to Vannevar Bush’s Memex . No one actually made a Memex as described, nor did they need to; instead, other inventors selected some of their favorite ideas from his vision, combined them with other ideas, and manifested them in entirely unexpected ways. The result was more than just more research ideas, but eventually products and entire networks of computers that have begun to reshape society.

How then, do research ideas indirectly lead to impact? Based on both the experience of HCI researchers and practitioners attempting to translate research into practice 2 2 Colusso, L., Jones, R., Munson, S. A., & Hsieh, G. (2019). A translational science model for HCI. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

Kalle Lyytinen, Jan Damsgaard (2001). What's wrong with the diffusion of innovation theory?. Working conference on diffusing software product and process innovations.

- Researchers must demonstrate feasibility . Until we know that something works, that it works well, and that it works consistently, it just doesn’t matter how exciting the idea is. It took Xerox PARC years to make the GUI feel like something that could be a viable product. Had it not seemed (and actually been) feasible, its unlikely Steve Jobs would have taken the risk to have Apple’s talented team create the Macintosh.

- Someone must take an entrepreneurial risk . It doesn’t matter how confident researchers are about the feasibility and value of an interface idea. At some point, someone in an organization is going to have to see some opportunity in bringing that interface to the world at scale, and no amount of research will be able to predict what will happen at scale. These risk-taking organizations might be startups, established companies, government entities, non-profits, open source communities, or any other form of community that wants to make something.

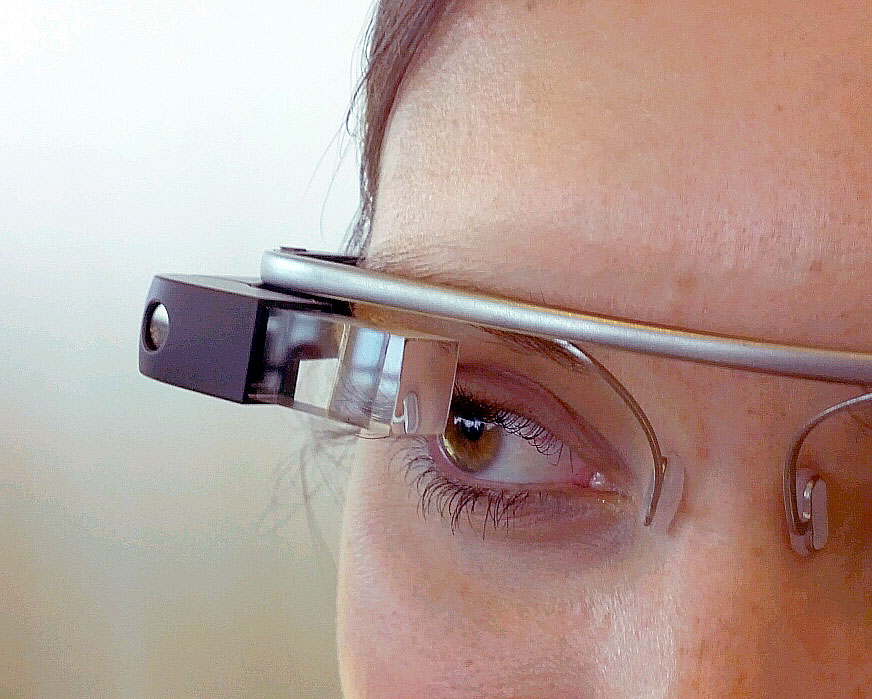

- The interface must win in the marketplace . Even if an organization perfectly executes an interface at scale, and is fully committed to seeing it in the world, it only lives on if the timing is right for people to want it relative to other interfaces. Consider Google’s many poorly timed innnovations at scale: Google Glass , Google Wave , Google Buzz , Google Video ; all of these were compelling new interface innovations that had been demonstrated feasible, but none of them found a market relative to existing media and devices. And so they didn’t survive.

Let’s consider four examples of interface technologies where these three things either did or didn’t happen, and that determined whether the idea made it to market.

Feasibility

The first example we’ll consider is what’s typically known as strong AI . This is the idea of a machine that exhibits behavior that is at least, if not more skillful than human behavior. This is the kind of AI portrayed in many science fiction movies, usually where the AI either takes over humanity (e.g., The Terminator ), or plays a significant interpersonal role in human society (e.g., Rosie the robot maid in the Jetsons ). These kinds of robots, in a sense, are an interface: we portray interacting with them, giving them commands, and utilizing their output. The problem of course, is that strong AI isn’t (yet) feasible. No researchers have demonstrated any form of strong AI. All AI to date has been weak AI , capable of functioning in only narrow ways after significant human effort to gather data to train the AI. Because strong AI is not feasible in the lab, there aren’t likely to be any entrepreneurs willing to take the risk of bringing something to market at scale.

Strong AI, and other technologies with unresolved feasibility issues (e.g., seamless VR or AR, brain-computer interfaces), all have one fatal flaw: they pose immense uncertainty to any organization interested in bringing them to market. Some technology companies try anyway (e.g,. Meta investing billions in VR), but ultimately this risk mitigation plays out in academia, where researchers are incentived to take high risks and suffer few consequences if those risks do not translate into products. In fact, many “failures” to demonstrate produce knowledge that eventually ends up making other ideas feasiible. For example, the Apple Newton , inspired by ideas in research and science fiction, was one of the first commercially available handheld computers. It failed at market, but demonstrated the viability of making handheld computers, inspiring the Palm Pilot, Tablet PCs, and eventually smartphones. These histories of product evolution demonstrate the long-term cascade from research feasibility, industry research and development feasibility, early product feasibility, to maturity.

Risk

Obviously inveasible ideas like strong AI are of course fairly obviously not suitable for market: something that simply doesn’t clearly isn’t going to be a viable product. But what about something that is feasible based on research? Consider, for example, some brain-computer interfaces have a reasonable body of evidence behind them . We know that, for example, it’s feasible to detect muscular activity with non-invasive sensors and that we can classify a large range of behaviors based on this. The key point that many researchers overlook is that evidence of feasibility is necessary but insufficient to motivate a business risk.

To bring brain-computer interfaces to market, one needs a plan for who will pay for that technology and why. Will it be a popular game or gaming platform that causes people to buy? A context where hands-free, voice-free input is essential and valuable? Or perhaps someone will bet on creating a platform on which millions of application designers might experiment, searching for that killer app? Whatever happens, it will be a market opportunity that pulls research innovations from the archives of digital libraries and researcher’s heads into the product plans of an organization.

And risk changes as the world changes. For example, some of the current uncertainties of brain-computer interfaces stem from limitations of sensors. As biomedical advances improve sensor quality in healthcare applications, it may be that just barely feasible ideas proven in research suddenly become much more feasibile, and therefore lower risk, opening up new business opportunities to bring BCIs to market.

Acceptability

Of course, just because someone sees an opportunity doesn’t mean that there actually is one, or that it will still exist by the time a product is released. Consider, for example, Google Glass , which was based on decades of augmented reality HCI research, led by Georgia Tech researcher Thad Starner . Starner eventually joined Google, where he was put in charge of designing and deploying Google Glass. The vision was real, the product was real, and some people bought them in 2013 (for $1,500). However, the release was more of a beta in terms of functionality. And people weren’t ready to constantly say “OK, Glass” every time they wanted it to do something. And the public was definitely not ready for people wandering around with a recording device on their face. The nickname “Glasshole” was coined to describe early adopters, and suddenly, the cost of wearing the device wasn’t just financial, but social. Google left the market in 2015, largely because there wasn’t a market to sell to.

Of course, this changes. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, investing in video chat software and augmented reality might have seemed like a narrow enterprise business oppoprtunity. After the pandemic, however, there are likely permanent shifts in how not just business, but families and communities, will stay synchronously connected online. The market for creative, versatile video chat, and even AR and VR, expanded within weeks, rapidly increasing the acceptability of staying at home to visit with distant friends, or having a meeting with a headset strapped on.

Adoption

Some interface ideas become feasible and acceptable enough to be viable products. For example, after decades of speech recognition and speech synthesis research, DARPA, the U.S. Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, decided to invest in applied research to explore a vision of personal digital assistants. It funded one big project called CALO (“Cognitive Assistant that Learns and Organizes”), engaging researchers across universities and research labs in the United States in creating a range of digital assistants. The project led to many spinoff companies, including one called Siri, Inc., which was founded by three researchers at SRI, International, a research lab in Silicon Valley that was charged with being the lead integrator of the CALO project. The Siri company took many of the ideas that the CALO project demonstrated as feasible (speech recognition, high quality speech synthesis, mapping speech to commands), and attempted to build a service out them. After a few rounds of venture capital in 2007, and a few years of product development, Apple acquired Siri, kept its name, and integrated it into the iPhone. In this case, there was no market for standalone digital voice assistants, but Apple saw how Siri could give them a competitive advantage in the existing smartphone market: Google, Microsoft, and Amazon quickly followed by creating their own digital voice assistants in order to compete. Once digital voice assistants were widely adopted, this created other opportunities: Amazon, for example, saw the potential for a standalone device and created the smart speaker device category.

Once interface technologies reach mass adoption, problems of feasibilty, risk, and acceptability no longer factor into design decisions. Instead, concerns are more about market competition, feature differentiation, the services behind an interface, branding, and user experience. By this point, many of the concerns we have discussed throughout this book become part of the everyday detailed design work of designing seamless interface experiences, as opposed to questions about the viability of an idea.

Barriers to innovation

What are the implications of these stories for someone in innovating industry? The criteria are pretty clear, even if the strategies for success aren’t. First, if an interface idea hasn’t been rigorously tested in research, building a product (or even a company) out of the idea is very risky. That puts a product team or company in the position of essentially doing research, and as we know, research doesn’t always work out. Some companies (e.g., Waymo), decide to take on these high risks, but they often do so with the high expectation of failure. Few companies have the capital to do that, and so the responsibility for high-risk innovations falls to governments, academia, and the few industry research labs at big companies willing to invest big risks.

Even when an idea is great and we know it works, there’s a really critical phase in which someone has to learn about the idea, see an opportunity, and take a leap to invest in it. Who’s job is it to ensure that entrepreneurs and companies learn about research ideas? Should researchers be obligated to market their ideas to companies? If so, how should researchers get their attention? Should product designers be obligated to visit academic conferences, read academic journals, or read books like this? Why should they, when the return on investment is so low? In other disciplines such as medicine, there are people who practice what’s called translational medicine , in which researchers take basic medical discoveries and try to find product opportunities for them. These roles are often funded by governments, which view their role as investing in things markets cannot risk doing. Perhaps computing should have the same roles and government investment.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, even when there are real opportunities for improving products through new interface ideas, the timing in the world has to be right. People may view the benefit of learning a new interface as too low relative to the cost of learning. There may be other products that have better marketing. Or, customers might be “locked in,” and face too many barriers to switch. These market factors have nothing to do with the intrinsic merits of an idea, but rather the particular structure of a marketplace at a particular time in history.

The result of these three factors is that the gap between research and practice is quite wide. We shouldn’t be surprised that innovations from academia can take decades to make it to market, if ever. If you’re reading this book, consider your personal role in mining research for innovations and bringing them to products. Are you in a position to take a risk on bringing a research innovation to the world? If not, who is?

Taking this leap is no small ask. When I went on leave to co-found AnswerDash in 2012 with my student Parmit Chilana and her co-advisor Jacob Wobbrock , it was a big decision with broad impacts not only on my professional life, but my personal life. We wrote about our experiences learning to sell and market a product 1 1 Chilana, P. K., Ko, A. J., & Wobbrock, J. (2015). From user-centered to adoption-centered design: a case study of an HCI research innovation becoming a product. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

Amy J. Ko (2017). A three-year participant observation of software startup software evolution. IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering, Software Engineering in Practice Track.

There are many ways to close these gaps. We need more contexts for learning about innovations from academia, which freely shares its ideas, but not in a way that industry often notices. We need more students excited to be translate, interpret, and appropriate ideas from research into industry. We need more literacy around entrepreneurship, so that people feel capable of taking bigger risks. And we need a society that enables people to take risks, by providing firmer promises about basic needs such as food, shelter, and health care. Without these, interface innovation will be limited to the narrow few who have the knowledge, the opportunity, and the resources to pursue a risky vision.

References

-

Chilana, P. K., Ko, A. J., & Wobbrock, J. (2015). From user-centered to adoption-centered design: a case study of an HCI research innovation becoming a product. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

-

Colusso, L., Jones, R., Munson, S. A., & Hsieh, G. (2019). A translational science model for HCI. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

-

Amy J. Ko (2017). A three-year participant observation of software startup software evolution. IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering, Software Engineering in Practice Track.

-

Kalle Lyytinen, Jan Damsgaard (2001). What's wrong with the diffusion of innovation theory?. Working conference on diffusing software product and process innovations.