Overview

Teaching at the University of Washington can be great fun. But it can also be really hard. I wrote this guide to help you maximize the fun and minimize the hard. Whether you’re a new teaching assistant, a novice teacher, or a lifelong teacher, I hope there’s something you can learn from it.

And the chances are good you will, because very few people who teach in higher education have ever had the opportunity to learn about the science of learning 1,2 1 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. National Academies Press..

National Research Council (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school: Expanded edition. National Academies Press.

Why listen to me? I don’t have a formal education in education, so I’m not fully versed in it’s complexities, but I’m not inexpert either:

- I’ve taught as a tutor and in classrooms since I was 14.

- I’ve taught in higher education since I was an undergraduate in 1999.

- I’ve read most of the seminal work on the science of learning and teaching.

- In 2010, I started doing research on the teaching and learning of computing.

- I’ve been teaching at UW since 2008, which gives me enough experience with recent history to have a sense of our campus culture and our undergraduates students.

- Students like my teaching: I regularly get 4.5 or higher on our (flawed and biased) student evaluations of teaching, which at least suggests that students perceive me as an effective teacher.

Of course, that hardly means I know everything: like all teachers, I’m still learning and improving. But I’m guessing you’re reading this because you think I have something to teach you about teaching.

Of course, as with any advice, there are some caveats:

- Some of the tips I give in this guide might be too adapted to my skills and personality. They might not work for you. Teaching methods aren’t equally adoptable by all teachers.

- I’ve studied a lot of the major literature in education and learning sciences, but I don’t have a Ph.D. in it, and I’m self taught. I might have some things wrong. I hope any experts who stumble upon this point these inaccuracies out.

- If you’re reading this, a lot of it is tailored to teaching at UW and in Informatics in particular. Much of the advice I share might only be relevant to our particular university and population.

With those disclaimers in mind, let’s start with a discussion of Informatics students at UW.

References

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. National Academies Press..

-

National Research Council (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school: Expanded edition. National Academies Press.

Students

Informatics students are incredibly diverse. They come from all over the world, have different perspectives and values, and have different short term and long term goals. Some are very career driven, some are very curious; some are grateful for their opportunity to be at UW, some are more entitled. We have international students from across the world (though mostly Asia), we have students from around the United States (though mostly west coast), and we have a small majority of students from around Washington state (though more western Washington than eastern). The university also attracts a large proportion of students who are the first in their families to attend college.

There are some generalizations I can make about our students because we try to admit students with particular goals and interests:

- They’re fascinated by information technology.

- They’re curious about the human, social, and ethical dimensions of technology (but not as curious as students in arts and the humanities).

- Many pursue Informatics because of the economic security it promises, not because of an intrinsic interest they have in designing or building information technology. (Though those interests develop as we teach them.)

- They are often very busy, with too many classes, too much part time work, too much commuting to campus, and too many side projects. They juggle a lot, and often are still learning how to juggle well.

- Most are very driven students. They want to learn, they want to have impact, and they want to create. This leads to high expectations of our teaching.

- Most have a utopian view of technology, rather than a dystopian one. This is shifting as society’s view of computing is becoming more nuanced, but our faculty are far more skeptical of information technology than our students.

- Informatics students support each other. It’s a very tight learning community, and they rely on each other to learn, to navigate their experiences, and to get information.

In some ways, there are similarities between Informatics students and Computer Science students. Students in both majors tend to pursue jobs in the software industry, for example. However, Informatics students tend to seek a more holistic view of computing, and are also curious about non-computational aspects of information, such as ethics, policy, human experience, human values, and society. Informatics students, due to their broader training, also pursue a broader set of careers beyond software engineering, filling roles across information technology companies.

While there are some consistencies in our students’ interest, there is considerable diversity in the resources they have to attend to learning, and often this is out of their control.

Here are some of the many factors I’ve encountered while teaching at UW:

- Some students don’t have good sleep hygiene , and therefore don’t sleep enough to stay awake in class. Let them sleep; they’re not going to learn anything if they’re barely conscious. And don’t set deadlines at midnight; that just incentivizes poor sleep hygiene.

- Some students live further away from campus every year and struggle to commute to campus reliably. Be tolerant of some variation in arrival times. Because you’re likely paid more than them, they likely commute much further than you do, and may experience greater uncertainty in their trips.

- As the cost of education at increases, some students are having to work more, sometimes full-time, to pay for their education. This might mean they can’t attend class or do homework. Remember that failure to do assigned work is not necessarily laziness, but more likely a carefully made choice about triaging time. Consider more flexible policies that support this triage.

- Some students experience significant hardship in school: poverty, hunger, sexual assault, deaths in the family, divorce, childcare obligations. School doesn’t shield against these things; and at UW, where we admit a high proportion of first generation college students, many of these are common experiences. It’s hard to focus on learning when there are bigger events in life. If you notice a student not submitting work, reach out to them and offer them campus resources; it’s more likely something difficult is happening in their life than that they are lazy.

- Some students have mental health issues that make it challenging to focus on learning. Our university provides some resources for students, but they’re far from adequate and many students do not utilize them. If a student seems to disappear from a course, sometimes mental health is the reason. Check in with them and see if they need help.

- Some of our students are not U.S. citizens and face a whole collection of anxieties, barriers, and sometimes threats. For example, even basic policies, such as international students inability to secure sufficient student work visas to land summer internships, result in inequities that put a greater stress on their career planning.

- Some of our students do not start at UW, but transfer from 2-year colleges from around the state, and sometimes other universities. While this is a widely pursued path, especially through the state’s Running Start program , many transfer students can take several quarters to adjust. Never assume that students know how university policies work, how to access learning technologies, or how to engage university services.

- Students come from all over the world, and so their prior knowledge from primary, secondary, and other education varies widely. University admissions has same basic minimum standards with respect to reading, writing, and math, but the assessments are not perfect. You may find yourself teaching students who still struggle to write coherent sentences and paragraphs, or reason algebraically.

- Some students have physical disabilities , such as blindness, deafness, low-vision, and other physical impairments that limit their ability to perceive or access the materials that teachers create. Use the many tools provided on campus to test the accessibility of your materials.

- Some students have invisible disabilities , including learning disabilities, attentional disorders, and chronic mental health problems, that limit their ability to read, sit for long periods of time without moving, or sustain motivation to learn. And because of stigma, many students do not disclose these. If you notice a student struggling, have a conversation about how you can help.

- Some students are not fluent enough in English to be able to use proper spelling or grammar. If you assess spelling and grammar, recognize that while this might result in learning, it also disadvantages students who haven’t had nearly as much time to master English.

- Some students overcommit , because they haven’t yet mastered tracking their commitments or managing their time.

- Some students don’t have a consistent, quiet, stable environment for studying . They may live with a large family, have many child-care responsibilities, or have an unstable home life.

- Some students, whether because of poverty or fasting for Ramadan, do not eat enough to remain alert in class, making it hard to focus on learning.

- Some students don’t have the money to have a computer or printer at home, or can’t afford printing at school. We try to offer enough rentals in iSchool IT, but students often do not know they can borrow them.

While all of this complexity in student experience can be overwhelming, I find it easiest to simply remember that students’ lives are as complex as ours. That doesn’t mean you have to coddle them, but it does mean you have to make some tough choices about what assumptions you want to make about what’s feasible and humane for them to do in your class. To be inclusive, make as few assumptions as possible.

Curriculum

Informatics is the study, design, and development of information technology for the good of people, organizations, and society. This means that the overarching objective of the Informatics curriculum is to give students both a conceptual and practical appreciation of how information is woven through society and its systems, how information technology supports these systems, how to design and build these systems, and how to make sense of information through quantitative and qualitative information.

Our faculty view information technology broadly: it includes not just computational technologies but also analog ones such as books, speech, and other media. And our faculty view information systems as more than just the internet: communities, organizations, libraries, and countless other ways of organizing people and information technology are all systems. We want students to leave with as broad of perspectives on information as our faculty have. This includes the empowering ability to create information systems by developing software. But it also includes the ability to criticize information technology, having a more nuanced and less utopian view of it’s role in society, and who information technology is serving.

To achieve these goals, our curriculum has several key courses:

- INFO 200 Intellectual Foundations provides a broad overview of critical perspectives on the design and impact of information systems in society.

- INFO 201 Technical Foundations provides a data-driven introduction to the development of software-based information technology and the computational analysis of data.

- INFO 300 Research Methods teaches how we gather and analyze data to answer questions.

- INFO 330 Databases and Data Modeling teaches how we represent, persist, and retrieve data representations of entities in the world.

- INFO 340 Client-side Development teaches how to create information technology for the internet

- INFO 350 Information Ethics and Policy teaches how to reason about values, rights, and laws related to information and intellectual property.

- INFO 360 Design Methods teaches how to envision, evaluate, and communicate new information systems.

- INFO 380 Information Systems Analysis teaches how to reason about and evolve information systems, especially those in organizations.

- INFO 3XX electives teach foundational ideas related to networking, cybersecurity, information assurance, information retrieval, and data science.

- INFO 4XX electives teach advanced topics in software development, data science, databases, design, ethics, cybersecurity, information assurance, and justice.

- INFO 490/491 Capstone I and II teach students how to apply everything they’ve learned above to solving information problems in teams.

With the courses above, most students leave with just enough knowledge to be productive entry-level UX designers, software developers, data scientists, and cybersecurity analysts. Many are also well positioned to be product managers and entrepreneurs, since they get such a holistic view on designing, creating, and evolving information technologies. Some students interested in research and data science also find that they need a masters degrees to compete for entry level jobs. Unlike many computer science majors, many end up in management and leadership positions after a few years because of their broader training.

There is still a disconnect between our goals in the curriculum and these outcomes. Students rarely learn enough to be excellent software developers (the same is true of CS majors), but they still get jobs. Students are rarely as critical of information technology as our faculty want them to be (but they are still more critical than most CS majors). Students’ broad training is often at the expense of depth, but this positions them well in the longer term to make change in organizations and the world. The short term goal of preparing them for careers and graduate school is often in tension with the long term goal of graduating sharp, intellectually curious, critical thinkers of information technology. It is our job as teachers to balance this tension.

Rules

In meeting the goals of the curriculum, there are a few rules we need to discuss. Whether you’re full-time faculty, guest faculty, a doctoral student, or a teaching assistant, there is one universal rule at our university: academic freedom .

Academic freedom, in the context of teaching, is the idea that unless someone explicitly says otherwise, you are free to teach how you want to teach, what you want to teach. That doesn’t free you from consequences of bad choices (students might not like you, and if you’re not protected by tenure, you might not get hired again or have your contract renewed). Your reputation is obviously at stake. And there are some rules and expectations, which I discuss below. But otherwise, our norms are generally to grant the same intellectual freedom that tenured professors have to all of our teachers.

One of the most important expectations is that you show up to class . We understand that sometimes you can’t. If you get sick, there are no substitutes. If you have travel, you may miss some teaching periods. When at all possible, you’re expected to find your own substitutes, find some way of attending class remotely, or assigning student work to make up for the missed teaching period. We keep this expectation partly because students are often paying hard won money to learn, and because we want students to learn.

Another expectation is that you teach to the learning objectives of the course. More often than not, these are not written down, or if they are, they are out of date or implicitly specified by a recent syllabus. We try to work hard to keep our documentation up to date, but opinions about what to teach evolve and the world evolves. We expect you to be resourceful, reaching out to our experts for guidance. The best way to make sure you’re achieving this is to share your syllabus, in advance of the course, with all of the recent teachers of the course. If you’re teaching a class of your own design, then you don’t have to coordinate or get approval from anyone (but you still might want feedback, as I discuss in the course design chapter).

A third expectation is that you submit grades for all students on time at the end of the quarter. We do offer a standard grading scale for converting percents to grade points, but there are no enforced rules about how you compute them, but we do expect grades to reflect, to the extent possible, the degree to which students met the learning objectives in the course. (This is often quite difficult to achieve, as I discuss in the grading chapter).

We also expect you to follow regulatory requirements . FERPA , for example, protects students’ privacy by requiring their permission to disclose “student records.” That means you can’t share grades or other evidence of learning that might be considered as a student record, including things like student work, grades of that work, or official communications about their work. This has implications on, for example, which learning technologies you use: you must either use FERPA-compliant software. If you choose not to, you’re responsible for ensuring that nothing that could be construed as a “student record” makes it to the cloud storage of a non-FERPA compliant provider. All that said, you can get a student’s permission and can prove you have it, if you want to share, for example, student work from a previous course offering.

Of course, this scarcity of rules and expectations, while quite freeing, also comes with great costs. It means that there’s huge variation in teaching approaches on campus, which can lead to innovation, but also great inconsistencies in student experience. And it puts a great burden on instructors to decide, fully, how they want to teach. The result is that most instructors just do what other people are doing (e.g., lecture), since that’s the path of least resistance. This harms meaningful innovation in teaching.

Learning

The expectations in the previous section are minimum expectations. They are so low, in fact, that any teacher at UW that only met them would not only not be hired, but definitely would not be promoted. We expect instructors to aim higher, and this begins with understanding how learning works.

There are many basic ideas from the science of learning that most people do not know. Below I’ll share some of this big ideas. While you read them, remember that many of your beliefs about learning are not necessarily informed by science, and be open to changing your beliefs.

We’ll begin with prior knowledge 7 7 Tobias, S. (1994). Interest, prior knowledge, and learning. Review of Educational Research.

To build efficiently on prior knowledge, learners need deliberate practice 3 3 Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review.

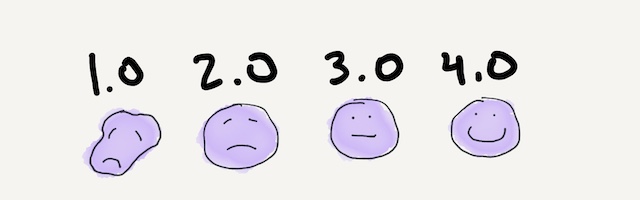

Closely related to practice is intelligence mindset 2 2 Carol S. Dweck (2018). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Books.

Another factor that shapes motivation is interest 5 5 Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist.

A third factor that shapes motivation is identity 8 8 Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Even if a student is motivated to learn, has a growth mindset, has an interest, and has an identity that aligns with a subject, structuring practice is still hard. One of the critical skills required to structure practice is self-regulation 9 9 Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist.

Even if learning is successful, it turns out that people rarely transfer their knowledge from one domain to another 4 4 Haskell, R. E. (2000). Transfer of learning: Cognition and instruction. Elsevier.

Whereas all of the ideas above are supported by many decades of research on learning, there are many common myths about learning:

- Lecturing is generally less effective than active learning methods. Active learning methods engage students in practicing skills, recalling knowledge, and synthesizing ideas, rather than just listening. Counterintuitively, learners may perceive active learning as less effective than great lectures, because they can lead to a sense of struggle and confusion, but this is because learners wrongly perceive the struggle to learn as not learning 1 1

Louis Deslauriers, Logan S. McCarty, Kelly Miller, Kristina Callaghan, Greg Kestin (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

. - Students do not have different “learning styles” 6 6

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological science in the public interest.

(e.g., “visual” learners, “auditory” learners). Learners do have preferences for media, which often come from diversity in learners attentional skills, physical abilities, language fluency, etc. But learners aren’t categorically “visual” or “auditory” learners, and serving students’ preferences does not improve in learning. That said, not meeting students’ needs (e.g., accessible materials in a language they can read) clearly affects learning. Moreover, not all methods for teaching a particular concept are equally effective for all learners, but that’s because of varying prior knowledge, not differences in ways people process information from different media. Attention should be on those inequities and less on negligible factors like whether something should be text, video, or sound (for content to be accessible, it should all of these). - There’s no such thing as “left brained” or “right brained” students. Most people have both hemispheres and we all use both of them fully. What people are usually thinking of when they say this is that personalities vary. They do, and teaching to varying personalities does require careful planning.

- There is no magic number of hours of practice (e.g., 10,000) that result in expertise. It’s the quality of practice that determines the pace of learning, and it’s a teacher’s job to help shape, structure, and motivate that practice.

- Praising intelligence does not help; it reinforces a fixed mindset, falsely signaling to students that they’re abilities come from an intrinsic trait rather than their effort. Praising effort and persistence does help, because it promotes a growth mindset.

- Students do not “discover” their passions. They develop interests, with the help of teachers, who can share new possible interests and give them positive experiences with those potential interests that eventually lead students to internalize them.

All of these ideas show that learning is purposeful, highly sensitive to a learners’ self, self-knowledge, and environment, and greatly shaped by the social context of learning, especially teachers.

References

-

Louis Deslauriers, Logan S. McCarty, Kelly Miller, Kristina Callaghan, Greg Kestin (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

-

Carol S. Dweck (2018). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Books.

-

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review.

-

Haskell, R. E. (2000). Transfer of learning: Cognition and instruction. Elsevier.

-

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist.

-

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological science in the public interest.

-

Tobias, S. (1994). Interest, prior knowledge, and learning. Review of Educational Research.

-

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

-

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist.

Teaching

Learning doesn’t necessarily require teaching. People can teach themselves, especially if they have good self-regulation skills. But the long list of things required for successful learning in the previous section shows why teaching is so valuable: great teachers provide purpose, provide resources, organize practice, develop identity, and structure environments conducive to learning.

Being an effective teacher requires three types of knowledge 1 1 Cochran, K. F., DeRuiter, J. A., King, R. A. (1993). Pedagogical content knowing: An integrative model for teacher preparation. Journal of Teacher Education.

- Content knowledge (CK). This is knowledge if your subject. If you don’t have this, you’ll quickly lose your authority. It’s okay to disclose that you don’t know something, but on balance, learners have to believe that you know more than them.

- Pedagogical knowledge (PK). This is knowledge of how to teach. I’m imparting some of this knowledge in this book, but most of this has to be acquired through practice. This includes the wide range of teaching methods, classroom management skills, and social and communication skills necessary for managing a group of learners’ attention.

- Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). This is knowledge of how to teach your subject. It turns out that every subject has its own teaching challenges. For example, knowledge of algebra and knowledge of teaching methods isn’t enough to teach algebra; you also have to know what’s hard about solving for x and how to help learners overcome difficulties solving for x.

Most teachers in higher education come with CK. Primary and secondary teachers, because they must be certified, learn some PK and PCK in school, and then more of both as they practice teaching. Most teachers in higher education, however, because they lack formal education in teaching, have to learn PK and PCK on their own (e.g., by reading guides like this). All teachers, to improve, and to acquire PCK, need the same elements of deliberate practice that all learners do: reflection on their teaching, targeted feedback on what is working and what is not, and repetition. Finding someone to coach you on your teaching (to teach you) can be an effective strategy for improving.

Some teachers in higher education might might even lack the CK they need to teach a subject. For example, someone might have a degree in computer science, but be tasked with teaching our server-side development course, which they might never have learned in school or industry. Before such a person can be an effective teacher of server-side development concepts, they need to gain enough CK to teach it. How much is enough? Certainly enough to teach to the learning objectives of the course, but probably more, as students will ask questions that test the depths of your knowledge. Find the time before you prepare to teach a subject to sufficiently master the subject. Perhaps ask for course release or extra compensation for that time to learn.

All that said, one of the biggest mistakes novice higher education teachers make is assuming that CK is enough to teach. This often manifests in teachers assuming they just need to present their knowledge for students to learn. Long lectures , for example, still ubiquitous in higher education teaching, are a perfect example of this: they provide information, but do little else. In fact, conventional lectures are incompatible with nearly everything we discussed about learning in the previous chapter:

- They assume attention . But every teacher and student knows that most students aren’t paying attention most of the time.

- They often assume interest . But as any student will tell you, most teachers just start explaining without spending nearly enough time establishing why they should care about a subject.

- They lack practice . The best a student can do during a lecture to practice is to start ignoring you, then practice and refine the ideas themselves.

Lectures miss the fundamental insight about effective teaching: that it is a fundamentally social activity. For a learner to learn from a teacher, they first have to trust a teacher, and then have to consent to giving up some authority to a teacher, so that the teacher can guide their learning. Learners can take back this authority at any point by simply moving their attention away from you: pulling out their smartphone, not doing their homework, or dropping out of a class. Therefore, a primary challenge in teaching is to earn trust, authority, and attention, and maintain it throughout a course.

Some students are willing to give authority for very little. In my experience, students from cultures where teachers are given much more respect grant authority almost unconditionally and perpetually. Students from the United States, however, where teachers are given less respect, often demand their teachers earn their trust. This means that a critical part of being an effective teacher is spending the first few class periods of a course purposefully developing that trust by demonstrating expertise, effective management of the classroom, clear communication, and clear expectations. If you don’t do this, you won’t have students’ trust, and therefore you won’t be able to teach them.

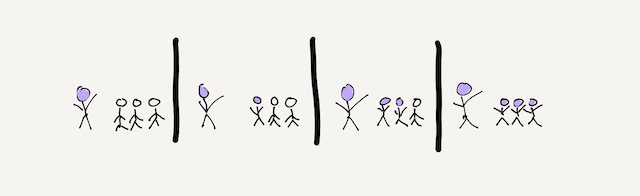

Suppose you do earn a students’ trust. How do you keep their attention? In our modern world, there are more distractions than ever from in and out of class learning, whether it’s smartphone notifications, a Netflix binge, or simply good old procrastination. The key to sustaining students’ attention is to not overuse it. In class, that can mean using active teaching methods , in which students do more than they listen. Even lectures can be active, including 5-10 minutes of instruction, then 5-10 minutes of activity. Few people can pay attention to one thing for more than half an hour. Respect this fact about attention fatigue and design around it, identifying ways of promoting practice in class.

Outside of class, students might face the same distractions, but have even less to incentivize attention, since you’re not their to engage them. Procrastination, one of the most significant deterrents to learning, has many causes. Students might not be interested; it’s your job to write materials that interest them. Students might not know how to get started; it’s your job to write materials that sufficiently scaffold and decompose the work so they know how to get started. Students might have poor time management skills; it’s your job to clearly communicate when things are due so they can make the most of the skills they do have.

Teachers, therefore, structure learning. They do it by being inspiring role models and mentors that catalyze interest. They do it by planning learning activities that promote a growth mindset and practice. And they do it by giving detailed, personalized feedback about students’ learning.

Unfortunately, some teachers do the opposite of these things:

- They reinforce a fixed mindset, portraying a world in which some students “get” it and some don’t.

- They humiliate students for not meeting expectations.

- They place the entire responsibility of structuring learning on students.

All of these behaviors abdicate a teacher’s responsibility to provide continued guidance, feedback, and encouragement.

Teaching is, therefore, as much about a way of being as it is about ways of teaching.

References

-

Cochran, K. F., DeRuiter, J. A., King, R. A. (1993). Pedagogical content knowing: An integrative model for teacher preparation. Journal of Teacher Education.

Courses

Given everything above about learning, teaching, and the diversity and complexity of students’ lives at UW, how should one design classes to promote effective learning? There are many ways, and I can’t enumerate them here, but I can enumerate some basic principles.

First, don’t just teach how you were taught . Think first: what are you teaching and how can you best support the learning of it through practice, given all of your students’ varying prior knowledge, the necessity of practice, and the complexity of students’ lives? Lectures, a midterm, and a final exam are rarely compatible with most of the above. You have the freedom to try any form of teaching that you believe might best promote equitable learning.

Once you free yourself of the bad teaching ideas from your past, the next step is to learn about your students’ prior knowledge . Ask others who’ve taught the same course what your students tend to know. Better yet, plan on measuring what your students know, either before the class starts, or at the beginning of class. Even informal self-reported knowledge of what students know can help you calibrate your expectations for how much and how quickly they might learn.

Once you have a sense of your students’ prior knowledge, decide how you want to set expectations . What do you want students to learn? What work will you ask them to do to meet these expectations? What kind of learning environment will help them meet those expectations? What kind of classroom norms will help them meet those expectations? Develop a narrative around all of these ideas, communicating why your students’ should be interested in the topic. Write a syllabus that communicates this narrative, explains how you’re going to teach, and specifies expectations.

A good syllabus covers the following details:

- What is the course about and why should students care?

- What materials do students need for the course (textbooks, devices, etc.)?

- What kind of work will students be expected to do, when is it due, and how long will it take?

- How will students’ efforts and learning be translated into a grade? (We’ll discuss grading in the next chapter).

- What norms do you expect students to follow in and out of class? This can cover how students treat you, how they treat each other, how they communicate, and the ethics of their conduct (e.g., plagiarism).

- What is the timeline of the course? How does it unfold over time and why does it unfold that way?

As you answer these questions, plan for students to join the class late, be sick, and be absent due to travel. Most of these absences are out of students control: registration for our courses is competitive, and travel is often due to family obligations, athletics, or job searches. A good course design is resilient to these absences. Have policies that account for all of them. For example, you might allow students to drop a few of the lowest scores of recurring activities and have alternative ways to learn when they miss something that occurs in class. Designing these alternate paths requires care, because the alternate route can become the preferred route if it is easier or more convenient.

Be prepared . Finish your syllabus well in advance of the quarter, get feedback on it from others who have taught the same or similar course, and finalize it before the first day of class. To the extent you can, plan every part of your course before you do it. Students will see that you’re prepared and they’ll take that seriously, meeting your expectations.

When class begins, teach your syllabus . Read it to the students in your class, and quiz them on it, so everyone knows the expectations before the quarter proceeds. This establishes your authority, the limits on your authority, and the rules by which students can plan the rest of their coursework and life around. Students will organize their time and quarter around your expectations. If you haven’t set them clearly, or you haven’t set them at all, they won’t be able to make room in their busy lives for the effort you expect them to give.

While setting clear expectations is paramount, change them when necessary . This especially true if your expectations were unclear. Don’t punish the students for your lack of clarity. And if you want room for a lack of clarity, set the expectation that they won’t get clarity, and are beholden to your whims. (Good luck getting most students to accept this). And if you go in the other direction mid-quarter, changing expectations to create more work, or make the course harder, expect retaliation: the students have carefully orchestrated their lives around the expectations you originally set. Changing the terms of the agreement is a violation of your contract.

To make sure you’re consistent about following the expectations you set, translate your syllabus into a task list with due dates. Convert every bit of preparation, grading, and notifications you can think of into a task, and remember to do it. The more you fail to meet your end of the expectations you set, the more authority you will lose, and the less students will meet your expectations. And that will be partially your fault, not theirs.

Design expectations that incentivize attention . For example, if you do not incentivize attendance to class in some way (a grade, or a grade that can only be obtained by attending class), some students will decide that other things in their life are more important (often justifiably). Or, if you do not incentivize paying attention to a lecture (it’s too long, it’s boring, it covers material that won’t be assessed), some students will decide to pay attention to other things during your lecture. Choose teaching methods that promote active learning, which not only make it hard for learners to attend to anything but the learning, but also make it fun.

Choose equitable teaching methods . Your job isn’t to detect high performers, it’s to make every student a high performer. For example, choose discussion formats that engage every student in the discussion, not just those bold enough to share their ideas in a large group. Think about how your choices of readings, activities, and ideas privileges or oppresses certain communities and individuals, not only in class, but in the world. If you’re not sure if your plans are equitable, talk to some of the faculty in the school with active learning expertise for guidance.

Once you have a syllabus prepared based on the principles above, test your syllabus against these principles. Are expectations clear? Have you conveyed why students should be interested? Have you built in ways to develop their interests? Have you selected methods for engaging and sustaining students’ attention? Check each of these aspects of your course and iterate when you find a flaw.

Grading

I’m not a fan of grading . But before I explain why, let me deconstruct what I mean by grading.

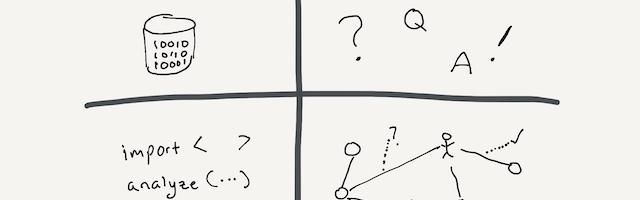

When we say grading, we’re usually referring to summative assessment . Summative assessments are essentially records of learning. They’re measurements taken at a moment in time of what someone knows. Most practices in higher education are to take all these snapshots and then aggregate them in some way, then record that as a final grade on a transcript. This is different from formative assessment which is diagnostic in nature: it helps measure what a learner does and doesn’t know, to support their deliberate practice.

Formative assessments are incredibly helpful. They provide targeted feedback for practice. They inform a teacher about what their students know. They give students a concrete idea of what they know and what they need to work on. And because the results of formative assessments are not a permanent record, the stakes for learners are lower, freeing them to focus on discovering what they know well and what they need to work on, instead of be paralyzed by test anxiety.

Summative assessments, in contrast, warp motivations. They’re confounded by all of the resource issues earlier in this guide in that they end up measuring students’ lack of resources rather than their knowledge. Worse yet, summative assessments are often used to allocate further resources (e.g., entry into a major, scholarships). This might all be fine if our measurements of learning were good and students had all the resources they needed to learn. Unfortunately, neither are the case.

Given this, I recommend you attempt to devise a grading scheme that is flexible enough to support diversity in student resources. Give abundant pass/fail opportunities to encourage practice and get formative assessment. Use low-stakes formative assessment as a tool to incentivize learning, while also giving you an opportunity for extensive feedback. Then, provide more focused, end-of-quarter opportunities for summative assessments. This approach to grading gives most of the quarter time for practice, then saves the archival measurement of knowledge for after the learning has occurred, not during.

You might be worried that this will lead to grade inflation . That’s a different issue. Grade inflation happens when faculty are afraid of retaliation for low grades. I’m recommending something different: clear expectations, a strong focus on personalized feedback and practice, and a targeted but limited application of summative assessment. Make the summative assessment half the grade if you like, so you still get a wide range of grade points if indeed there is a large variation in learning. That will have the consequence of motivating learners to attend to the feedback you give throughout the quarter, to the extent they believe the practice is relevant to the end of quarter assessment.

Regrades might sound like another path to grade inflation, but in reality, they’re just an opportunity for students to get more feedback and get further practice. Give students as many regrade opportunities as you’re willing to spend time on, and they will learn more. Better yet, rather than allowing for regrades, build repeated submission and feedback on assignments into your grading. Give some credit for earlier submissions, then summatively assess later submissions.

Remember, if the goal is for everyone to learn, then success at teaching means that everyone gets a well-deserved 4.0. Try to design your grading scheme and syllabus to achieve this. And if students get low grades in such a scheme, remember that it is at least partly your failure as a teacher to not promote effective learning.

If all of this sounds far too permissive, I encourage you to reflect on your motives. Is your goal for some to succeed and some to fail? Are you still operating with a belief that only some students are capable of learning what you’re teaching, and grades are supposed to detect who those students are? Or is your goal for everyone to learn? If it’s the latter, than a widely varying distribution of scores is failure at that goal.

Conflict

Even in this best case scenario, some things will go wrong. And if you’re less prepared along any of these dimensions, many things might go wrong.

More often than not, the reason things go wrong is because of mismatched or vague expectations . If you’re not clear about what you want students to do, they either won’t do them, won’t do them to the level you expect, or will be frustrated that they don’t know what you want. If your classroom norms don’t set clear expectations, and you don’t enforce them, students won’t follow them, and your class culture will break. And the list continues: in group work, in labs taught by TAs, in grading, and every other dimension of your course, if you’re not clear about what you want, students will be frustrated, they will seek more guidance, and in the worst case scenarios, they’ll escalate to a higher authority (e.g., the program chair of Informatics or the Associate Dean for Academics) to try to create pressure for you to set your expectations more clearly, or meet the expectations they brought to the class.

Some of these challenges are inevitable. For example, when designing a course, you can’t perfectly anticipate what expectations students will bring, what prior knowledge they will bring, or what norms they will bring. If these are in conflict with your expectations, you’re going to have to resolve conflict. And in some cases, no amount of planning or clear communication change students’ expectations: some will want so strongly, for example, to learn a specific technology, that if you refuse to teach it, they will be frustrated and initiate conflict. And in many of these cases, they will be justified: your authority and expertise aren’t absolute; you may be wrong or have misjudged what students need to effectively learn.

So what can you do when conflict arises? Let’s first consider conflict around authority . Suppose a student isn’t happy with what you’re teaching or how you grade something because you didn’t meet their expectations. Do you assert your authority? Do you try to persuade them you’re right? Do you just do what they ask? And do you just do it for them? Regardless of what you might think is “right” in this scenarios (that’s a value judgement), none of these approaches really work. The only reliable way to resolve conflict around authority is to listen and then make a judgement . This shows that you understand their concern, that you’ve considered their concern in light of all of the circumstances, and that you’re willing to admit at least partial fault. More often than not, I find myself making judgements about how much my design choices and communication led to the problem, and give students slack to the extent I was to blame. Sometimes I’m entirely to blame and I decide to change my decision, sometimes I decide the student is entirely to blame and I hold firm. But in all cases, I listen, decide, and clearly explain my rationale.

This general pattern of conflict resolution plays out somewhat differently depending on the nature of the conflict. For example, suppose a student comes to you with a disagreement about a grade (the most common conflict at UW). Patiently listen to their concern. Take the time you need to reflect on whether the expectations you set about grading were vague, and if you need more information about the student’s interpretation of your expectations, ask them. Take time to deliberate on where the responsibility lies (it might have been shared), and brainstorm ways you might remedy the confusion. You might even promise to get back to them with a decision after you’ve had time to decide. Importantly, if you decide to change a policy on grading, announce that change for all students. Otherwise, you’ll violate students’ (reasonable) expectations of fairness.

Sometimes students will come with conflicts about what you’ve chosen to teach or how you’ve chosen to teach. More often, they’ll come to a higher authority with these concerns. In these cases, just as with the grade-related cases, it’s key to be vulnerable, listen to the feedback, and figure out how you might improve. Alternatively, maybe you really believe you did make the right choice of learning objectives; then it’s on you to better explain (or re-explain) the rationale behind your choice.

Some conflicts may arise between students and a teaching assistant that you’re supervising. In these cases, it’s still important to listen and decide, but it’s equally important to help educate your TA about how to resolve conflicts themselves. They’ll likely face the same conflicts that you do about grades and learning objectives, but they have even less authority with which to manage the conflict. If they’re escalating the conflict to you, it may be because they don’t know how to resolve it, or it may be that they don’t have sufficient authority to resolve it. They’re in the same situation as you, but for smaller scale conflicts.

Many Informatics classes involve teamwork , which can also be a source of great conflict. Just as with conflict between you and a student, conflicts between students also arise from mismatched expectations. Your role in these situations is help mediate conflict between students to align expectations, and better yet, teach students explicitly how to properly set expectations between themselves and resolve conflicts that arise. As with all of the other forms of conflict above, listening, authority, and vulnerability are central.

Sometimes you won’t be able to resolve these conflicts on your own. For example, some conflicts are so large that you don’t have the authority to resolve them. That’s okay. That’s why the iSchool has an Informatics program chair and a Dean for Academics. It’s our job to help you resolve conflicts, and if you can’t resolve them yourself, then make the decisions on your behalf. This escalation path is best for situations where you feel like you’ve either lost your authority, or a student is so resistant to your authority that you need a greater authority to make a decision.

Practice

You can’t learn how to teach from a book. But you can learn how to learn how to teach from a book. Here are some of the key ideas that should anchor your practice as an Informatics teacher:

- Students’ lives are just as complicated as yours, often more so. Because of this, students often lack the resources necessary to meet your learning expectations. Remember this, design for this, and problem solve around this.

- Informatics aims to educate lifelong critics, designers, and developers of information technologies that make the world a better place. Teach enough skills to help students secure their first job or get into graduate school, but also teach towards their whole life and career, positioning them to make social change through information.

- The academic freedom that UW bestows upon you is a blessing and a curse. It gives you the freedom to experiment and leverage your expertise, but that places a lot of responsibility on you to envision your course and to be compliant with law. It also requires you to coordinate with our faculty to ensure some degree of consistency between classes.

- Learning is more complicated than you think. It requires prior knowledge, attention, motivation, interest, identity, practice, and feedback. When students lack these things, they don’t learn. Get good at identifying what resources students are bringing.

- A teacher’s primary job is to structure an environment that provides the resources necessary to learn. Students are responsible for exploiting that environment, and you’re responsible for adjusting it if it’s not working Remember this division of labor and design around it. If you don’t, you’ll erode the trust at the foundation of your authority, which prevents you from teaching.

- Designing a good course requires clearly communicating the learning environment you’ve designed and setting clear expectations about how to engage in that environment. If you’re not prepared, you can’t communicate these things clearly.

- Use formative assessments to measure learning and diagnose misconceptions. Summative assessments are best after learning has occurred, where the threat of a permanent outcome to a grade can do the least damage to motivation, interest, and identity.

- All courses, no matter how well designed and planned, lead to conflict. Manage it by listening, and finding compromises that share in blame for misunderstandings about expectations.

How can you put these into practice? Reflect . Reflect on your teaching; keep a diary about what’s going well and what’s not. Reflect on your teaching with other teachers in the Information School; seek advice and problem solve. And as you reflect, be vulnerable and open to feedback, so that you can improve. Teaching, as with any skill that requires deliberate practice, relies on regular and targeted feedback. The faculty and students in our school are here to provide it.

Good luck with your teaching!