Grading

I’m not a fan of grading . But before I explain why, let me deconstruct what I mean by grading.

When we say grading, we’re usually referring to summative assessment . Summative assessments are essentially records of learning. They’re measurements taken at a moment in time of what someone knows. Most practices in higher education are to take all these snapshots and then aggregate them in some way, then record that as a final grade on a transcript. This is different from formative assessment which is diagnostic in nature: it helps measure what a learner does and doesn’t know, to support their deliberate practice.

Formative assessments are incredibly helpful. They provide targeted feedback for practice. They inform a teacher about what their students know. They give students a concrete idea of what they know and what they need to work on. And because the results of formative assessments are not a permanent record, the stakes for learners are lower, freeing them to focus on discovering what they know well and what they need to work on, instead of be paralyzed by test anxiety.

Summative assessments, in contrast, warp motivations. They’re confounded by all of the resource issues earlier in this guide in that they end up measuring students’ lack of resources rather than their knowledge. Worse yet, summative assessments are often used to allocate further resources (e.g., entry into a major, scholarships). This might all be fine if our measurements of learning were good and students had all the resources they needed to learn. Unfortunately, neither are the case.

Given this, I recommend you attempt to devise a grading scheme that is flexible enough to support diversity in student resources. Give abundant pass/fail opportunities to encourage practice and get formative assessment. Use low-stakes formative assessment as a tool to incentivize learning, while also giving you an opportunity for extensive feedback. Then, provide more focused, end-of-quarter opportunities for summative assessments. This approach to grading gives most of the quarter time for practice, then saves the archival measurement of knowledge for after the learning has occurred, not during.

You might be worried that this will lead to grade inflation . That’s a different issue. Grade inflation happens when faculty are afraid of retaliation for low grades. I’m recommending something different: clear expectations, a strong focus on personalized feedback and practice, and a targeted but limited application of summative assessment. Make the summative assessment half the grade if you like, so you still get a wide range of grade points if indeed there is a large variation in learning. That will have the consequence of motivating learners to attend to the feedback you give throughout the quarter, to the extent they believe the practice is relevant to the end of quarter assessment.

Regrades might sound like another path to grade inflation, but in reality, they’re just an opportunity for students to get more feedback and get further practice. Give students as many regrade opportunities as you’re willing to spend time on, and they will learn more. Better yet, rather than allowing for regrades, build repeated submission and feedback on assignments into your grading. Give some credit for earlier submissions, then summatively assess later submissions.

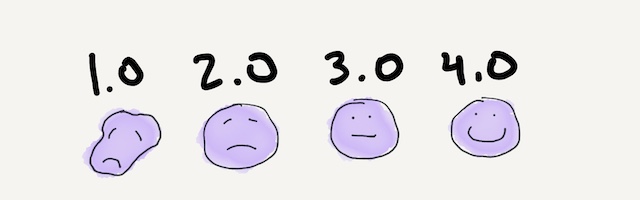

Remember, if the goal is for everyone to learn, then success at teaching means that everyone gets a well-deserved 4.0. Try to design your grading scheme and syllabus to achieve this. And if students get low grades in such a scheme, remember that it is at least partly your failure as a teacher to not promote effective learning.

If all of this sounds far too permissive, I encourage you to reflect on your motives. Is your goal for some to succeed and some to fail? Are you still operating with a belief that only some students are capable of learning what you’re teaching, and grades are supposed to detect who those students are? Or is your goal for everyone to learn? If it’s the latter, than a widely varying distribution of scores is failure at that goal.