Information + democracy

The first time I was eligible to vote was in the 2000 U.S. elections. I was a sophomore in college. As an Oregonian, voting was a relatively simple and social affair. I was automatically registered to vote. About one month before the election, I received a printed voter’s pamphlet that gave the biographies and positions of all of the candidates, as well as extensive arguments for and against various ballot measures (a form of direct democracy that bypassed the state legislature). Two weeks before the election, I received my ballot. My roommates and I organized a dinner party, gathering friends to step through each decision on the ballot together, making the case for and against each candidate and issue. At the end of the night, we had completed our ballots, shared our positions on the issues, and went outside to place them in the secure mailbox on our street.

Two years later, when I moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, my voting experience in the mid-term elections was quite different. I wasn’t automatically registered; doing that required submitting a registration form and proving my residence. There didn’t seem to be a mail-in ballot process or information online, so I went to the local library to ask about voting. They told me to go to my local polling place on election day, but they had no information about where my polling place was. I asked my neighbors and they said it was at the local elementary school a mile away. There was no voter’s guide, and so I had to read the news to keep track of who was running and what their positions were, and watch television to see their advertisements. And on election day, I memorized who and what I was voting for, walked with my daughter to the school, and then waited in a line for 45 minutes. Inside, I had to show my ID, then enter a voting booth, then punch holes in a large, confusing paper ballot machine with a mechanical arm, while I tried to recall my position on various candidates and issues. My daughter and I left with some civic pride at having expressed our preferences, but I longed for the sense of community I had in Oregon, where voting was on my schedule, in my home, with my friends, family, and community.

Both of these stories are at the heart of democracy, where individuals, with their communities, gather information about people and issues, use that information to develop preferences around how society should work, and then express those preferences through voting, where their preferences are either directly implemented, or implemented by elected representatives. This entire process is, in essence, one large information system, designed to ensure that the laws by which we govern ourselves reflect our wishes. In the rest of this chapter, we will discuss the various parts of this information system, surfacing the critical roles that information plays in ensuring a functioning democracy. Throughout, we will focus on the United States, not because it is the only or best democracy, but because it is the longest active democracy. But throughout, we will remember that there are democracies all over the world, as well as countries with different systems of government, each influencing each other through politics, culture, and trade.

Information and political systems

There are many forms of political systems that humanity has used in history. One of the first might simply be called anarchyanarchy: The absense of any form of government. , in which there are no governing authorities or laws that regulate people’s interactions. In these societies, the primary force driving social interactions is whatever physical power or intellectual advantage a person have bring to protect themselves, their property, and their community. In an anarchy, information may play a role in securing individual advantage, but otherwise has no organized role in society, since there is no society. Such a system maximizes individual choice, but at the expense of safety, order, and human rights.

Authoritarianauthoritarianism: A system of government that centralizes power. systems centralize power in one or more elite leaders, who handle all economic, military, foreign relations, leaving everyone else with no power or representation, and usually a strict expectation of obedience to those leaders. These include military dictatorships in which the military controls government functions, single-party dictatorships like that in China or North Korea, or monarchic dictatorships, in which power is centralized in kings, queens, and people of other royal descent inherent power. In authoritarian systems, leaders tend to tightly control information, as well as spread disinformation, in order to keep the public uninformed and retain power. For example, authoritarian governments rely heavily on public education and public ownership of the media to indoctrinate youth with particular values 9 9 John R. Lott, Jr. (1999). Public schooling, indoctrination, and totalitarianism. Journal of Political Economy.

Chris Edmond (2013). Information manipulation, coordination, and regime change. Review of Economic Studies.

Harsh Taneja, Angela Xiao Wu (2014). Does the Great Firewall really isolate the Chinese? Integrating access blockage with cultural factors to explain Web user behavior. The Information Society.

Democracydemocracy: A system of government that distributes power. , in contrast to anarchy and authoritarianism, is fundamentally an information-centered political system 2 2 Bruce Bimber (2003). Information and American democracy: Technology in the evolution of political power. Cambridge University Press.

Arthur Lupia (1994). Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: Information and voting behavior in California insurance reform elections. American Political Science Review.

Michal Tóth, Roman Chytilek (2018). Fast, frugal and correct? An experimental study on the influence of time scarcity and quantity of information on the voter decision making process. Public Choice.

Brian Randell, Peter YA Ryan (2006). Voting technologies and trust. IEEE Security & Privacy.

Systems of government, of course, do not operate in isolation. Our modern world is global and interconnected; people move across the world, sharing ideas, culture, practices, and information. What happens in one country like the United States or China affects what happens in other countries, whether this is a law that is passed or a shift in culture.

Political speech as information

In the United States’ democracy, one of the central principles underlying an informed public is a notion of free speech . Its first amendment, for example, reads:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

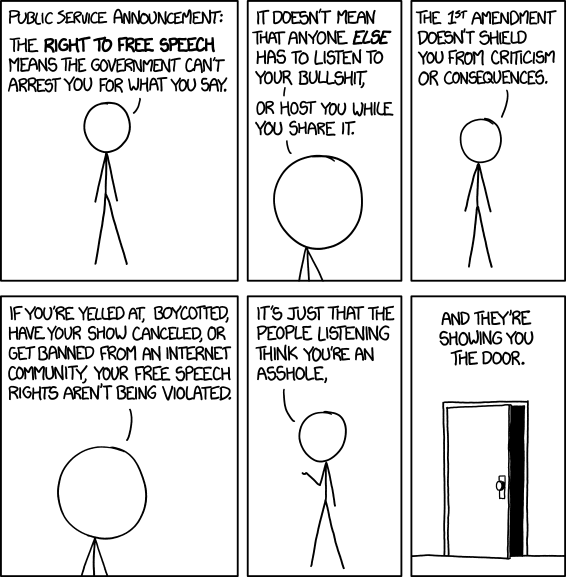

Underlying this law is the idea that people should be free—in the sense that the government shall not constrain—what people believe or say and who they organize with to say it, especially when they are saying something about the government itself. However, also implicit in this statement is that it only limits the government from abridging or limiting someone’s speech: it says nothing about a business limiting someone’s speech by removing them from a platform, or firing them as an employee; it says nothing about a community banning someone from a forum in which they are speaking; and it certainly says nothing about enforcement of limits on speech in homes, places of worship, or other private settings. The limit, at least in the U.S., is primarily on the government. In fact, part of the protection the government is offering is the freedom for individuals and private enterprises to censor as they see fit, without government intervention.

Of course, in the U.S., and in many other countries, there are some forms of speech that the government can limit, often concerning speech that does harm. In the U.S., libel is an illegal form of defamation in print, writing, pictures, or signs that harms someone’s reputation, exposes someone to public hatred. Slander is a similar form of defamation made orally. Both tend to require proof of damage. Other laws in the U.S. also limit fraud, child pornography, speech that is integral to illegal conduct or incites illegal actions. Therefore, even in the U.S., which is regarded as having some of the strongest speech protections, speech has limits, and political speech is included in these limits.

Political speech, of course, is the foundation of information systems that ensure an informed public to support democratic decisions. It ensures that communities can form around issues to advocate for particular laws or representatives 21 21 Emily Van Duyn (2020). Mainstream Marginalization: Secret Political Organizing Through Social Media. Social Media+ Society.

Many debates about politics concern limits on speech. For example, should politicians be able to take limitless money from any source to support their campaigns? This campaign financing question is fundamentally about whether giving money is a form speech. If it is, then the 1st amendment would say yes: the government has no role in limiting that speech. But if it is not speech, then the government may decide to pass laws to place limits on campaign donations, as it has in the past. Of course, what counts as speech is closely tied to what counts as information: giving money is clearly one way to send a signal, but it also entails granting economic power at the same time. Perhaps the difficulty of separating the information and resources conveyed in donations is why it is so tricky to resolve as a speech issue 7 7 Deborah Hellman (2010). Money Talks but It Isn't Speech. Minnesota Law Review.

Other questions concern the role of private business in politics in limiting political speech. For example, newspapers have long had reporters that attend U.S. presidential press briefings, and editorial boards that decide what content from those briefings might be published. These editorial judgments about political speech have rarely led to controversy, because there are multiple papers that make different editorial judgments. But social media platforms, as a different kind of publisher, are in the same position, protected by the 1st amendment by the right to decide what speech is allowed on their platforms, with the option of limiting speech. For example, on January 8th, 2021, Twitter permanently suspended the account of former President Trump after he incited mob violence on the U.S. capital. And then, shortly after, Amazon decided to withdraw web hosting support to Parler , a popular Twitter clone often used by right-leaning politicians and individuals, notable for its strict free speech commitments. Both of these cases are examples of private enterprise limiting political speech, firmly protected by the 1st amendment, by engaging in content moderation 22 22 Sarah Myers West (2018). Censored, suspended, shadowbanned: User interpretations of content moderation on social media platforms. New Media & Society.

Notably, there are no speech protections in the U.S. or other countries that outlaw lies, disinformation, or misinformation in politics. Politicians can misrepresent their positions, spread false information, lie about their actions and intents, and intentionally deceive and manipulate the public with information. As long as it does not incite illegal activity or provably cause damage, lying and deception are generally legal (although not without social consequence). Because the U.S. government currently has no policy that speaks to how to handle lies and deception in political contexts, it is left to the public and private organizations to manage it. Some social media sites flag it, and link to fact checks; others limit its amplification; others simply let it be. Individuals are then left to make their own judgments about the speech when forming their political preferences. Some argue that social media has accelerated and amplified radicalization and conspiracy theories, fragmenting political information landscapes 11 11 Andrew Marantz (2020). Antisocial: Online extremists, techno-utopians, and the hijacking of the American conversation. Penguin Books.

Clay Shirky (2011). The political power of social media: Technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Affairs.

Kate Starbird, Ahmer Arif, Tom Wilson (2019). Disinformation as collaborative work: Surfacing the participatory nature of strategic information operations. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction.

Because the political information systems in democracies are so free, diverse, and varied in their purpose, synthesizing information into informed political preferences is challenging. Newspapers publish opposing viewpoints; advertisements might lie, misrepresent, and deceive; politicians themselves in public debates might focus more on rhetoric than policy; and social media, written by people with myriad motives, and amplified by platforms and a public that spends little time evaluating the credibility of what they are sharing, create noisy feeds of opinion. If democracies rely on an informed public to make sensible votes, modern information systems only seem to have made making sense of this information more challenging.

Voting information systems

However a person forms their political preferences in a democracy, preferences ultimately become votes (if someone decides to vote). Votes are data that convey a preference for or against a law or for or against a representative. Because votes in a democracy are the fundamental mechanism behind shaping policy and power, voting systems, as information systems, have strict requirements:

- They must reliably capture someone’s intent. In the 2000 U.S. elections, for example, this became a problem, as some of the paper balloting systems in the state of Florida led to ambiguous votes (known as “ hanging chads ”), and debates about individual voter’s intents.

- They must be secure 23 23

Scott Wolchok, Eric Wustrow, J. Alex Halderman, Hari K. Prasad, Arun Kankipati, Sai Krishna Sakhamuri, Vasavya Yagati, and Rop Gonggrijp (2010). Security analysis of India's electronic voting machines. ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security.

. It is critical that each individual only votes once and that votes are not changed. This requires tracking voter identity and having an auditing trail to verify that the vote, as captured, was not modified, and was tallied correctly. - They must be accessible 12 12

Tetsuya Matsubayashi, and Michiko Ueda (2014). Disability and voting. Disability and Health Journal.

. If someone cannot find how to vote, cannot find where to vote, cannot transport themselves to record a vote, cannot read the language in which a ballot is printed or displayed, or cannot physically record their vote because of a disability, they cannot vote.

All of these are fundamentally information system problems, and without faith that all of these properties are maintained, the public may lose faith in the power of voting as a way to express their preferences. This happened in Florida when ballots with hanging chads were tossed out. This happened in the 2020 U.S. elections with (unfounded) fear of mail-in ballot security. And it has happened throughout U.S. history as the country and it’s states have made voting harder for Black people, disabled people, and immigrants not fluent in English to vote (and only after centuries of not allowing Black people and women to vote at all). And it continues to happen in many states through strict voter ID laws, voter purging that effectively unregisters individuals from voting rolls, and reductions in the hours and availability of polling places 1 1 Carol Anderson, Dick Durbin (2018). One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy. Bloomsbury.

Rene R. Rocha, Tetsuya Matsubayashi (2013). The politics of race and voter ID laws in the states: The return of Jim Crow?. Political Research Quarterly.

But voting alone is only part of voting information systems. Laws also shape how votes are tallied, aggregated, and used to distribute power. For example, in the United States, state legislatures and the U.S. Congress are composed of elected representatives from different regions of the country. These regions, usually called districts , are geographical boundaries. These boundaries are drawn by politicians, and for some time, have been drawn in a way that clusters voters with similar preferences together, to limit their influence on elections. For example, a common strategy is drawing boundaries around Black neighborhoods, so all of the Black vote is concentrated toward electing one representative, limiting their impact on the election of other representatives. This practice, called gerrymandering 13 13 Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal (2009). Does gerrymandering cause polarization?. American Journal of Political Science.

George C. Edwards III (2019). Why the Electoral College is bad for America. Yale University Press.

Laws as information

Whatever the outcome of voting, and however votes are tallied, the result is a temporary granting of power to make, enforce, or interpret laws. Like speech and voting, lawmaking is requires information systems as well.

Consider, for example, the problem of knowing the laws: one cannot follow the laws if one does not know them, and yet actually seeing the law can be challenging. One source of information about laws is public signage: speed limit signs, for example, efficiently communicate driving laws, and parking signs attempt to explain parking laws. Law enforcement, such as police, might be a source of information about laws: if you violate a law and they see it, or are notified of it, they may communicate the law to you; they may arrest you, and communicate the charge against you only after you are in jail. At one point, the state of Georgia actually had its laws behind a paywall , preventing residents from even accessing the law without money. In contrast, the Washington state legislature’s Revised Code of Washington website , makes all of the state’s laws freely searchable, browsable, and accessible to anyone with access to a web browser. Even such websites, however, do not make it easy to know which laws apply to our behavior, as they may use language or ideas we do not know, or may need to be legally interpreted.

Another kind of information system is the process by which elected representatives make laws. Representatives might have committee meetings, they might draft legislation for comment by other legislators, they may hold public meetings to solicit feedback about laws, and they may hold votes to attempt to pass laws. Democracies vary in how transparent such processes are. For example, in some U.S. states, only some of these processes are public and there is no information about other legislative activities. In contrast, in Washington state where I live, there is a public website that makes visible all of the committee schedules, agendas, documents, and recordings , including features for tracking bills, tracking representative activity, and even joining a list of citizens who want to give testimony at meetings. These varying degrees of transparency provide different degrees of power to individuals to monitor and shape their representative’s activities.

Lobbyists, who advocate to lawmakers around particular issues 5 5 Richard L. Hall, and Alan V. Deardorff (2006). Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review.

Law enforcement, including everything from parking enforcement, to police, to federal fraud investors and internal ethics committees, also relies on and interfaces with information systems. Internally, they may gather data about crimes committed, keeping records of crimes, gathering information evidence. Some law enforcement agencies in the U.S. have even gone as far as using crime data to make predictions about where future crimes might occur, to help them prioritize their policing activities. Because these data sets encode racist histories of policing, the predictions are racist as well 6 6 Bernard E. Harcourt (2008). Against prediction: Profiling, policing, and punishing in an actuarial age. University of Chicago Press.

Lastly, the interpretation of law is central to democracy, but is also fundamentally an information system, as with law making. In the United States, judges and lawyers primarily interpret the law. Their job is essentially one of reading the text of laws and prior decisions and trying to test the specific details of a case against the meaning of the law and prior decisions about it. This process is inherently one concerned with information 16 16 Manavalan Saravanan, Balaraman Ravindran, and Shivani Raman (2009). Improving legal information retrieval using an ontological framework. Artificial Intelligence and Law.

While all information systems are important to someone for some reason, few information systems affect everyone in a democracy. Democratic information systems, however are an exception: the means by which we get political information, the systems we use to vote and to access and understand laws are fundamental to our basic rights and safety, and essential to preventing democracies from resisting authoritarianism or anarchy 8 8 Steven Levitsky, Daniel Ziblatt (2018). How Democracies Die. Crown.

Podcasts

For more about information and democracy, consider these podcasts:

- If You Were on Parler, You Saw the Mob Coming, Sway, NY Times . Host Kara Swisher interviews Parler CEO John Matze, who defended the platform’s lack of content moderation as a neutral town square, even after the violent insurrection at the U.S. capitol on January 6th. His positions in this interview led Amazon to stop providing web hosting on January 11th, 2020.

- Deplatforming the President, What Next, Slate . Host Lizzie O’Leary discuss the history behind content moderation and Twitter’s decision to suspend the president’s account.

- Shame, Safety and Moving Beyond Cancel Culture, The Ezra Klein Show, NY Times . Host Ezra Klein faciliates a discussion with YouTuber Natalie Wynn (ContraPoints) and writer Will Wilkinson about the culture of shame that underlies social media cancellation mobs, and the surprising ways this culture might be eroding democracy.

- The People Online Justice Leaves Behind, What Next: TBD . Discusses how those at the margins in the U.S. justice system were even less well-served online.

- How Minnesota Spied On Protesters, What Next: TBD . Discusses police surveillance of protestors.

References

-

Carol Anderson, Dick Durbin (2018). One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy. Bloomsbury.

-

Bruce Bimber (2003). Information and American democracy: Technology in the evolution of political power. Cambridge University Press.

-

Chris Edmond (2013). Information manipulation, coordination, and regime change. Review of Economic Studies.

-

George C. Edwards III (2019). Why the Electoral College is bad for America. Yale University Press.

-

Richard L. Hall, and Alan V. Deardorff (2006). Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review.

-

Bernard E. Harcourt (2008). Against prediction: Profiling, policing, and punishing in an actuarial age. University of Chicago Press.

-

Deborah Hellman (2010). Money Talks but It Isn't Speech. Minnesota Law Review.

-

Steven Levitsky, Daniel Ziblatt (2018). How Democracies Die. Crown.

-

John R. Lott, Jr. (1999). Public schooling, indoctrination, and totalitarianism. Journal of Political Economy.

-

Arthur Lupia (1994). Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: Information and voting behavior in California insurance reform elections. American Political Science Review.

-

Andrew Marantz (2020). Antisocial: Online extremists, techno-utopians, and the hijacking of the American conversation. Penguin Books.

-

Tetsuya Matsubayashi, and Michiko Ueda (2014). Disability and voting. Disability and Health Journal.

-

Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal (2009). Does gerrymandering cause polarization?. American Journal of Political Science.

-

Brian Randell, Peter YA Ryan (2006). Voting technologies and trust. IEEE Security & Privacy.

-

Rene R. Rocha, Tetsuya Matsubayashi (2013). The politics of race and voter ID laws in the states: The return of Jim Crow?. Political Research Quarterly.

-

Manavalan Saravanan, Balaraman Ravindran, and Shivani Raman (2009). Improving legal information retrieval using an ontological framework. Artificial Intelligence and Law.

-

Clay Shirky (2011). The political power of social media: Technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Affairs.

-

Kate Starbird, Ahmer Arif, Tom Wilson (2019). Disinformation as collaborative work: Surfacing the participatory nature of strategic information operations. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction.

-

Harsh Taneja, Angela Xiao Wu (2014). Does the Great Firewall really isolate the Chinese? Integrating access blockage with cultural factors to explain Web user behavior. The Information Society.

-

Michal Tóth, Roman Chytilek (2018). Fast, frugal and correct? An experimental study on the influence of time scarcity and quantity of information on the voter decision making process. Public Choice.

-

Emily Van Duyn (2020). Mainstream Marginalization: Secret Political Organizing Through Social Media. Social Media+ Society.

-

Sarah Myers West (2018). Censored, suspended, shadowbanned: User interpretations of content moderation on social media platforms. New Media & Society.

-

Scott Wolchok, Eric Wustrow, J. Alex Halderman, Hari K. Prasad, Arun Kankipati, Sai Krishna Sakhamuri, Vasavya Yagati, and Rop Gonggrijp (2010). Security analysis of India's electronic voting machines. ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security.