How to understand problems

As I mentioned I Chapter 1 , I subscribe to the view that design is problem solving. But without a clear understanding of what a “problem” is, how can it be solved? What does it mean to “solve” something anyway?

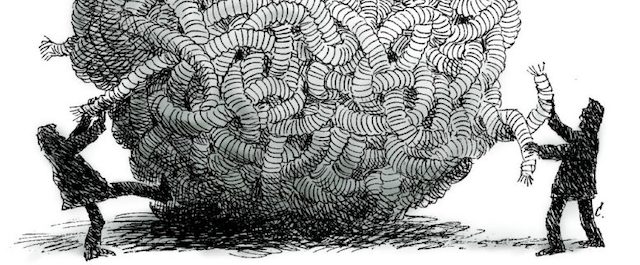

The problem is, once you really understand a problem, you realize that most problems are not solvable at all. They’re tangled webs of causality, which one might call “wicked” problems 3 3 Coyne, R. (2005). Wicked problems revisited. Design Studies.

Note how the “solutions” to the problems are all incremental: they change a few parts of a broken system, which leads to great improvements, but the problem is never “solved”.

What then is a “problem” if a problem is always complex and always changing? Herb Simon said, “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” 6 6 Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. MIT Press.

Now, that doesn’t mean that a situation is undesirable to everyone . For one person a situation might be undesirable, but to another, it might be greatly desirable. For example, most gambling addicts wish it was harder for them to gamble, but casinos are quite happy that it’s easy to gamble. That means that problems are inherently tied to specific groups of people that wish their situation was different. Therefore, you can’t define a problem without being very explicit about whose problem you’re addressing. And this requires more than just choosing a particular category of people (“Children! Students! The elderly!”), which is fraught with harmful stereotypes. It requires taking quite seriously the question of who are you trying to help and why , and what kind of help do they really need? And if you haven’t talked to the people you’re trying to help, then how could you possibly know what their problems are, or how to help them with design?

Therefore, the essence of understanding any problem is communicating with the people. That communication might involve a conversation, it might involve watching them work, it might involve talking to a group of people in a community. It might even involve becoming part of their community, so that you can experience the diversity and complexity of problems they face, and partner with them to address them.

In fact, it might even involve people themselves showing their problems to you.

Consider, for example, this video, by blind YouTuber Tommy Edison, who wanted to demonstrate the utter and complete design failures of ATMs at banks:

Why was it so hard for him to find the headphone jack? No one on the design team had any clue about the the challenges of finding small headphone jack holes without sight. They did , however, include a nice big label above the hole that said “Audio jack”, which of course, Tommy couldn’t see. Diebold, the manufacturer of the ATM had a wrong understanding of the problem of blind ATM accessibility. All of these show how they failed at the most basic task in understanding design problems: communicating with stakeholders.

By now, you should be recognizing that problems are in no way simple. Because everyone’s problems are personal and have different causes and consequences, there is no such thing as the “average user” 7 7 Trufelman, A. (2016). On average. 99% Invisible.

If you’re clever, perhaps you can find a design that’s useful to a large, diverse group. But design will always require you to make a value judgement about who does and who does not deserve your design help. Let that choice be a just one, that centers people’s actual needs. And let that choice be an equitable one, that focuses on people who actually need help (for example, rural Americans trying to access broadband internet, or children in low income families without computers trying to learn at home during a pandemic—not urban technophiles who want a faster ride to work).

How then, do you communicate with people to understand their problems?

There are many ways, including:

- Surveys communicate with people in a structured, asynchronous, impersonal way, getting you large scale insight, but in a way that can be unintentionally overly structured, biased on who responds, and shallow in insight.

- Interviews communicate with people in a synchronous, personal, semi-structured way, getting you deeper insights —assuming you have established good rapport— but at the cost of more time and a smaller range of people.

- Observations communicate with people by connecting you with their spaces, their practices, their collaborations, and their communication with others, revealing the inherent richness and complexity of their world, but with an even greater time commitment than interviews.

- Secondary research does not communicate with people, but leverages insights that others have gained from communicating with people, and published in research papers, books, and other sources.

These are just a few of hundreds of methods, each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

Let’s discuss two in more detail, to give you a sense of their tradeoffs.

Interviews

The essential quality of an interview is you asking someone questions and them giving you open ended answers.

Interviews can vary in how formal they are, ranging from a fully prepared sequence of questions to more of a conversation. They vary in how structured they were, ranging from a predefined list of questions in a particular order to a set of possible questions you might ask in a particular order.

The art and science of planning and conducting interviews is deep and complex 5 5 Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2011). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Sage.

There are a few basic things to avoid in your questions.

- Don’t ask leading questions, which suggest the answer that you want. (“is there any part of bus riding you actually enjoy?” vs. “tell me about your experiences on buses”).

- Don’t ask loaded questions, which don’t imply a desired answer but still contain implicit assumptions that may not be true (“have you stopped riding the bus?” assumes that a person rides the bus)

- Avoid double-negatives , which require careful logic to untangle (“are you not dissatisfied with your transit options?”)

When you prepare for an interview, try to do the following:

- Define a focus so that my questions center around a theme relative to my design goals.

- Brainstorm set of possible questions that you hope will teach me about the problem I’m trying to understand.

- Review the questions for the issues above, identifying any wording issues or assumptions.

- Prepare an organized list of the questions that you want to ask.

- Find a few people that you think will have insights about the problem you’re trying to understand and schedule time to interview them, estimating how long the interview will take.

- “Pilot” the interview, testing the questions and seeing how long they take, refining the questions, the timing, and the order until it best achieves the goals of your focus.

- Schedule as many interviews as you have time for, recording each one with permission, either as handwritten notes or audio

- During an interview, first establish rapport, sharing things about yourself so that my informant trusts you and is willing to share things about themselves.

- With all of those notes or audio, analyzing what everyone said, synthesizing a perspective on what the problem is.

For examples of great interviews, consider any of those by Fresh Air host Terry Gross . She’s particularly good at establishing rapport, showing sincere interest in her guest, and asking surprising, insightful questions that reveal her guests’ perspectives on the world.

Interviews are flawed and limited in many ways. They are out of context; they require people to remember things (which people tend not to do well). That means your understanding of a problem could be biased or flawed based on fabricated memories, misrepresentations, or even lies. Another downside of interviews is that participants may change their responses to please the interviewer or conform with societal expectations for how a person should behave, based on the context of the interview. This is called participant response bias 4 4 Dell, N., Vaidyanathan, V., Medhi, I., Cutrell, E., & Thies, W. (2012). Yours is better! Participant response bias in HCI. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

Contextual Inquiry

The second method we’ll talk about is the exact opposite of an interview: rather than asking someone to tell you about their life in the abstract, you directly observe some aspect of their life and have them teach you about it.

You go to where someone works or lives, you watch their work or life, you ask them about their work or life, and from these observations, make sense of the nature and dynamics of their work or life.

This approach, called Contextual Inquiry , is part of a larger design approach called Contextual Design 1 1 Beyer, H., & Holtzblatt, K. (1997). Contextual design: defining customer-centered systems. Elsevier.

I’m not going to cover the whole method or approach here, but these are the basics:

- Like an interview, define a focus . There’s too much to observe to see everything, so you have to decide what to pay attention to.

- Perform an inquiry in a real context.

- Create a partnership between you and your informant. You act as an interested learner, they act like a knowledgable expert. It should feel like a master/apprentice relationship.

- Don’t generate questions in advance; think of them as you observe.

- Focus on questions about the work that is happening in context.

- Record audio, photos, notes, and any other raw data you can use later to interpret

As with an interview, once you have your data, it’s time to step back and interpret it. What did you see? What implications does it have for the problem you’re solving? How does it change your understanding of the problem?

Here’s an example of what a contextual inquiry looks like and feels like:

This contextual inquiry is good in that it happens in context: the inquiry happens in an actual grocery store, in the place where the student shops. However, it fails in that the debrief devolves a bit into an interview, out of context. There’s nothing wrong with interviews, but that’s not the point of a contextual inquiry: the answers he provides to questions outside the grocery store are likely to be different in subtle but important ways than if he had been asked in context.

Like interviews, contextual inquiries are not perfect. They’re extremely time consuming and so it’s rare that you can do more than a few in a design project. That makes it hard to generalize from them, since you can’t know how comparable your few observations are to all of the other people in the world you might want to design for.

There is no right method for understanding problems. Every design context has its own constraints, whether money, time, skill, or circumstance. Consider, for example, the COVID-19 pandemic, which required many people to work from home to prevent community spread. Suddenly, designers who might have wanted to observe people in their work spaces with a contextual inquiry might mean observing their work at home . How could they watch someone using a computer, when the only camera in someone’s home might be the one pointing at their face? Every design situation requires a careful account of context; effective designers simply know their options and choose the right method for the situation.

Of course, if one is following the operating principles of design justice 2 2 Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. MIT Press.

References

-

Beyer, H., & Holtzblatt, K. (1997). Contextual design: defining customer-centered systems. Elsevier.

-

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. MIT Press.

-

Coyne, R. (2005). Wicked problems revisited. Design Studies.

-

Dell, N., Vaidyanathan, V., Medhi, I., Cutrell, E., & Thies, W. (2012). Yours is better! Participant response bias in HCI. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

-

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2011). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Sage.

-

Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. MIT Press.

-

Trufelman, A. (2016). On average. 99% Invisible.