What designers do

When I was an undergraduate, I didn’t have a clue about design. Like most students in technical fields, I thought design was about colors, fonts, layout, and other low-level visual details. I knew enough about user interfaces to know that design mattered , I just didn’t know how much or why.

Then I went to grad school to get a Ph.D. at Carnegie Mellon’s Human-Computer Interaction Institute , where I studied not only computer science and behavioral sciences, but design as well, combining these fields together into my expertise in Human-Computer Interaction. Suddenly I was surrounded by designers, and taking design classes with design students in design studios. Quickly I learned that design was much, much more than what was visible. Design was where ideas came from. Design was methods for generating ideas. It was methods for evaluating ideas. It was ways of communicating ideas. I learned that design was problem solving 4 4 Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development.

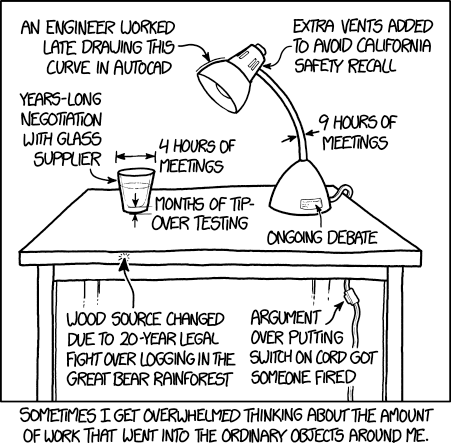

After some time, I also realized that if design was problem solving, then we all design to some degree. When you rearrange your room to better access your clothes, you’re doing interior design. When you create a sign to remind your roommates about their chores, you’re doing information design. When you make a poster or a sign for a club, you’re doing graphic design. We may not do any of these things particularly well or with great expertise, but each of these is a design enterprise that has the capacity for expertise and skill.

Many people design extensively, but not professionally. For example, there are countless communities that come together to design, learn, and envision futures, all without formal design education, and yet still creating all kinds of things that sustain people in their communities. Consider LOL! , a makerspace in the Fruitvale district of Oakland, California, which is part of the Bay Area Consoritium of hackerspaces, and brings together people of color, immigrants, women, youth, transgender, queer, and low-income communities. Together, members of the local community come together to teach and learn design skills, to bring together art, crafts, computer programming, and electronics to meet the specific needs of the community, whether they might be food, energy, clothing, shelter. All of this is design , albeit without the venture capital, design degrees, and profit motive.

What does it mean to do design professionally then? In way, professional design is just design for pay, in a formal organization, often (but not necessarily) with a profit motive. Consider all of the job titles that have a little (or a lot) of professional design embedded in them:

- Graphic designers take information and find ways to present it in a way that efficiently engages people in understanding that information. As a grad student, I took several graphic design courses and learned just how hard this is to do (not the least of which because the Adobe Creative Suite has such a steep learning curve).

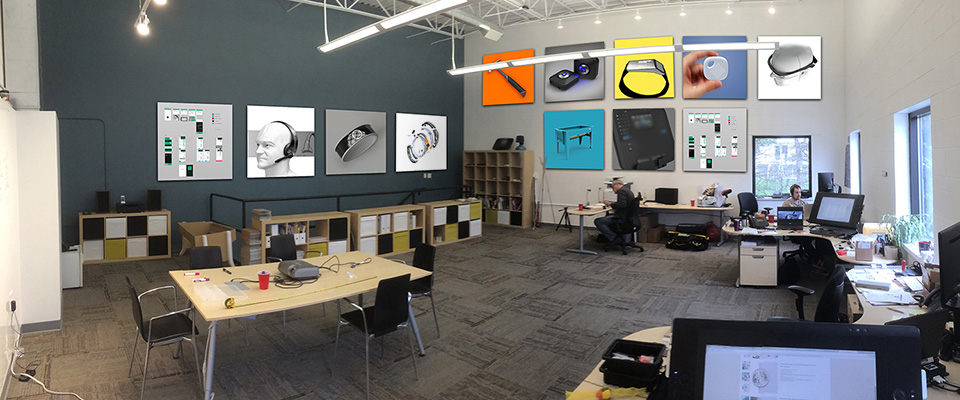

- Interaction designers envision new kinds of interactions with interactive technologies, usually as part of design consultancies. Some work on contract, helping other companies envision new products, others work “in-house”, designing for their company. Many of the graduates of the University of Washington’s Masters in Human-Computer Interaction + Design become interaction designers.

- User experience (UX) designers design and prototype user interfaces, defining the functionality, flow, layout, and overarching experiences that are possible in a product. In many bigger companies, UX designers determine what software engineers build.

- User experience (UX) researchers understand problems deeply so that designers can envision solutions to those problems or improve existing products.

- Product designers/managers investigate market opportunities and technical opportunities and design products that capitalize on those opportunities in a competitive landscape. The person that envisioned Airbnb ? A product designer. Mark Zuckerberg when he envisioned Facebook with the help of his investors and co-founders? A product designer.

- Software engineers do many kinds of design. They design data structures, algorithms, and software architectures. Front end developers occasionally help with interaction design, unless they work in an organization that has dedicated interaction designers.

In professional contexts, design is often where the power is. Designers determine what companies make, and that determines what people use. But people with the word “design” in their job title don’t necessarily possess this power. For example, in one company, graphic designers may just be responsible for designing icons, whereas in another company, they might envision a whole user experience. In contrast, many people without the word design in their title have immense design power. For example, some CEOs like Steve Jobs exercised considerable design power over products, meaning that other designers were actually beholden to his judgement. In other companies (some parts of Microsoft, for example), design power is often distributed to lower-level designers within the company.

What is it that all of these design roles have in common? They all involve these essential skills:

- Seeking multiple perspectives on a problem (sometimes conflicting ones). There’s no better way to understand what’s actually happening in the world than to view it from as many other perspectives as you can.

- Divergent thinking . This is the ability to creatively envision new possibilities. When designers consider alternatives in parallel 2 2

Dow, S. P., Glassco, A., Kass, J., Schwarz, M., Schwartz, D. L., & Klemmer, S. R. (2010). Parallel prototyping leads to better design results, more divergence, and increased self-efficacy. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI).

, they design better things. - Convergent thinking . This is the ability to take a wide range of possibilities and choose one using all of the evidence, insight, and intuition you have.

- Exploiting failure . Most people avoid and hide failure; designers learn from it, because behind every bad idea is a reason for it’s failure that should be understood and integrated into your understanding of a problem.

- Externalizing ideas as sketches, prototypes, writing, and other forms. By doing this, designers express details, often revealing which parts of an idea are still ill- or undefined.

- Maintaining emotional distance from ideas. If you’re too attached with an idea, you might not see or accept a better one that you or someone else discovers.

- Seeking critique . No one has enough perspective or knowledge to know everything good and bad about design on their own. Seeking the perspective of others on an idea helps complete this picture.

- Justifying decisions . No design is acceptable to everyone. Designers must be able to justify a choice, compare it to alternative choices, and explain why the choice they made is the “best” choice relative to the tradeoffs.

In a way, all of these skills are fundamentally about empathy 5 5 Wright, P., & McCarthy, J. (2008). Empathy and experience in HCI. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

...designers tend to unconsciously default to imagining users whose experiences are similar to their own. This means that users are most often assumed to be members of the dominant and hence “unmarked” group: in the United States, this means (cis) male, white heterosexual “able-bodied,” literate, college educated, not a young child and not elderly, with broadband internet access, with a smartphone, and so on. Most technology product design ends up focused on this relatively small, but potentially highly profitable, subset of humanity. Unfortunately, this produces a spiral of exclusion, as design industries center the most socially and economically powerful users, while other users are systematically excluded on multiple levels

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. MIT Press.

Given all of these skills, and the immense challenges of enacting them in ways that are just, inclusive, anti-sexist, anti-racist, and anti-ableist, how can one ever hope to learn to be a great designer? Ultimately, design requires practice. And specifically, deliberate practice 3 3 Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Rmer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review.

References

-

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. MIT Press.

-

Dow, S. P., Glassco, A., Kass, J., Schwarz, M., Schwartz, D. L., & Klemmer, S. R. (2010). Parallel prototyping leads to better design results, more divergence, and increased self-efficacy. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI).

-

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Rmer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review.

-

Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development.

-

Wright, P., & McCarthy, J. (2008). Empathy and experience in HCI. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).