The Panda Syndrome II:

Innovation, Discontinuous Change, and LIS Education

Stuart A. SuttonAssociate Professor

School of Library and Information Science

University of Washington: Seattle

311 Old Electrical Engineering Building, Box 352930

Seattle, WA 98195-2930

Phone: 206-685-6618

Fax: 206-616-3152

Email: sasutton@u.washington.edu

http://faculty.washington.edu/sasutton/

Journal of Education for Library and Information Science [In press] © 1998 Stuart A. Sutton

Abstract

This article explores the notion of punctuated equilibria in ecological theory and its application to library and information studies (LIS) educational institutions and the LIS profession. We use two separate lenses to explicate the roles of incremental and discontinuous change in the life of organizations in general and LIS organizations in particular. The first lens is the ecological model of organizational change and renewal set out by Michael Tushman and Charles O’Reilly. Tushman and O’Reilly provide a framework for examining the inevitable discontinuities produced through significant innovations which they define as technologies and services that produce a shift in the standard practices of a community that makes them more effective at what they do. The second lens is Peter Denning’s research paths to innovation. Denning’s perspective of research in the academy questions the existing emphasis on the generation of new ideas as the only true path to meaningful innovation. The article asks whether LIS educational institutions are educating professionals capable of functioning in the face of the inevitable discontinuities brought about through significant innovation. Equally significant, the article asks whether LIS professionals are capable of functioning as change agents in the processes of discontinuous change.

1. Introduction

In The Panda Syndrome: An Ecology of LIS Education, Van House and Sutton (1996) propose that the present and future existence of library and information studies education (LIS) can be viewed through a prism of ecological theory. They note that ecology has been used to explain not only the strategies that allow biological species to survive environmental change (Wilson, 1992), but also populations of organizations (Hannan and Freeman, 1989), and the population of professions as they seek to establish or maintain jurisdictional niches (Abbott, 1988). Here, we extend the work of Van House and Sutton by addressing a question to which they only allude: “What happens in ecological theory when a species (be it a biological species, an organization, or a profession) is confronted with something other than the slow processes of incremental change?” In other words, what determines survival when environmental change is rapid, dramatic, and discontinuous?

In general, it is commonly assumed that dinosaurs evolved over millions of years through measured incremental change driven by the forces of natural selection that held some changes more adaptive to the environment than others. Then, for the dinosaurs, a cataclysmic environmental event—a discontinuous change—spelled extinction. We posit here that the lives (and the extinction) of organizations including Library and Information Studies (LIS) academic institutions and the LIS profession are also formed and evolve in the face of two inevitable types of change: slow, stable, incremental change punctuated by rapid, discontinuous change. The focus of this article is on the latter and the complex balance LIS professionals, the profession, and LIS education must maintain in an information environment in which the cycles of slow, stable, incremental change and rapid discontinuous change grow shorter as a result of the increase in developments in information technologies and the social and economic contexts of information.

We examine the complex balance between the two types of change through two separate lenses. First, we use Tushman and O’Reilly’s (1996; 1997) model of the ambidextrous organization in which both forces of change must be accommodated.1 Central to Tushman and O’Reilly’s thesis is the notion of innovation-induced discontinuities. We (as did Tushman and O’Reilly) adopt Denning’s (1996, p. 27) definition of innovation as “a shift in the standard practices of a community that makes them more effective at what they do.”

We assert that synthetic organisms (organizations and professions), unlike their biological counterparts, can ride the wave of what Tushman and O’Reilly call innovation streams by creating forms of discontinuous change that shape the environment in which they exist. In a broad sense, the Tushman and O’Reilly model comports with the position held by Bourdieu (as expressed in The Panda Syndrome) that individuals and groups succeed not only in terms of the defined field of competition but by influencing “the rules and standards by which success is defined, the currency of the competition, the players, and even the boundaries of the playing field.”

Our second lens is Denning’s explication of the four research paths to innovation (1996; 1997): (1) the generation of new ideas, (2) the generation of new practices, (3) the generation of new products, and (4) the generation of new business. Denning provides a framework for designing learning environments in which the processes that lead to innovation can be inculcated.

In the following discussion, we first present Tushman and O’Reilly’s model of innovation within the context of the ambidextrous organization. Emphasis will be placed on their perception of the two types of change that drives the ecology of organizations. First we assume that libraries and other information centers are subject to the same competitive forces as other organizations competing to provide information services and products, and, therefore, that they are subject to the same competitive forces that drive both incremental and discontinuous change in ecological systems. We then move to the central question of the article: “How do we build learning environments that support the development of professionals able to design, implement, and manage ambidextrous organizations that drive the processes of innovation in services and products?”

Having framed the central question in terms of Tushman and O’Reilly’s model and Denning’s typology, we conclude by asking whether the profession’s current matrix of perceptions and appreciations (Van House and Sutton, pp. 139-140)—what Bourdieu calls a people or an institution’s “habitus”—is capable of absorbing and institutionalizing the dexterity necessary for survival in the midst of discontinuous change. More critically, we ask: “Can the profession come to grips with the institutionalization of ongoing innovation, the balancing of incremental and induced discontinuous change, and the educational ramifications of such a balancing for its professional members?”

2. The Tushman and O’Reilly Model: Punctuated Equilibria

Biological evolutionary theory has held that the processes of adaptation to the environment by biological species was one of gradual incremental change across generations. Some of those changes were properly aligned with the environment while others proved maladaptive resulting in extinction—part of the process we call natural selection. But all environmental change is not gradual. Tushman and O’Reilly (1996, p.12) note that in times of rapid change in the environment such as dramatic shifts in the food supply or severe changes in weather, “[r]eliance on gradual change was a one-way ticket to extinction.” Instead of a steady-state of environmental change, the reality is one of “punctuated equilibria”—long periods of gradual change “interrupted periodically by massive discontinuities.” In such cases, survival goes to those species that are lucky enough to possess characteristics appropriate to the new environment.

Tushman and O’Reilly observe (1996, p. 12) that research in organizational ecology “has successfully applied models of population ecology to the study of sets of organizations in areas as diverse as wineries, newspapers, automobiles, biotech companies, and restaurants. The results confirm that populations of organizations are subject to ecological pressures in which they evolve through periods of incremental adaptation punctuated by discontinuities.” Any number of forces may shape these discontinuities including “technology, competitors, regulatory events, or significant changes in economic or political conditions. For example, deregulation in the financial services and airline industries led to waves of mergers and failures as firms scrambled to reorient themselves to the new competitive environment.” (Tushman and O’Reilly,1996, p.11) Faced with such discontinuous change, the goals of management is “reconstituting their organizations to adjust to the new environment.”

Tushman and O’Reilly observe (1996, p.11):

“The real test of leadership, then, is to be able to compete successfully by both increasing the alignment or fit among strategy, structure, culture, and processes, while simultaneously preparing for the inevitable revolutions required by discontinuous environmental change. This requires organizational and management skills to compete in a mature market (where cost, efficiency, and incremental innovation are key) and to develop new products and services (where radical innovation, speed, and flexibility are critical). A focus on either one of these skill sets is conceptually easy. Unfortunately, focusing on only one guarantees short-term success but long-term failure.”

Tushman and O’Reilly’s work demonstrates that organizations, unlike their biological counterparts, need not face environmental discontinuities armed solely with luck. In fact, given the right culture, it is possible for an organization to help engineer to some degree through innovation the occurrence, frequency, and timing of environmental discontinuity even as it maintains productive incremental change with existing services and products—i.e., by performing as an ambidextrous organization. The not so obvious difficulty in the development of an ambidextrous organization is the willingness to build an organizational culture in which some part of the organization is focused on incremental and architectural change in services or products while another plots the demise of those same services and products through significant innovation. The goal, then, is to supplant existing services and products through innovation before the competition gets around to doing so. CEO Platt of Hewlett Packard states: “We have to be willing to cannibalize what we’re doing today in order to ensure our leadership in the future” (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1997, p. 216).

Chief among the factors resulting in the successful design of an ambidextrous organization is the capacity to maintain a dichotomous organizational culture—one that is “simultaneously tight and loose.” (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996, p. 26) They are sufficiently tight to leverage organizational structure, strategy, and processes in support of incremental change while sufficiently loose in their support of alternative subcultures where the entrepreneurial spirit of significant innovation can occur. If necessary, the ambidextrous organization is prepared to separate cultures embodying the two types of change in order to guarantee the survival of both.

“The bottom-line is that ambidextrous organizations learn by the same mechanism that sometimes kills successful firms: variation, selection, and retention. They promote variation through strong efforts to decentralize, to eliminate bureaucracy, to encourage individual autonomy and accountability, and to experiment and take risks. This promotes wide variations in products, technologies, and markets. It is what allows the managers of an old HP instrument division to push their technology and establish a new division dedicated to video servers. These firms also select ‘winners’ in markets and technologies by staying close to their customers, by being quick to ‘kill’ products and projects.” (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996, p. 28)

The concept of “engineering history” in organizational evolution is enticing as a link to Tushman and O’Reilly’s model of the role of innovation in the evolution of organizations. In the broadest sense, innovation is a form of social engineering. March, in his analysis of the “engineering of evolutionary history” states (1994, p. 46):

“Engineering is not the simple art of making changes. It is the art of improvement. The engineering of transportation is an effort to improve outcomes by intervening in the process of movement. The engineering of health is an effort to improve the outcomes by intervening in the process of disease. The engineering of history is an effort to improve outcomes by intervening in the processes of history. We ask not whether we can produce change—which within a branching, meandering history may be relatively easy—but whether we can produce change that can be relied on to be an improvement.”

March (1994, p. 47) provides an explicit statement regarding strengthening organizational evolutionary processes that is congruent with Tushman and O’Reilly’s model of the ambidextrous organization that balances measured, incremental change (what March would consider organization evolution based on “exploitation”) with induced discontinuous change (what March would consider organizational evolution based on “exploration”):

“[I]t is possible to argue that organizational engineering involves simultaneous improving the processes by which organizations seek out or generate new options (exploration) and improving their capabilities for implementing options that prove effective (exploitation). Organizations are engineered so as to facilitate experimentation and protect deviant ideas from premature elimination. At the same time, they are engineered to allow the identification, routinization, and extension of known good ideas. With inadequate exploration, an organization suffers from not having experiments with new options from which it can learn about new possibilities. With inadequate exploitation, an organization suffers from not eliminating bad experiments and not utilizing good ones. [¶]An engineering strategy of maintaining a balance between exploration and exploitation is an attractive goal. Unfortunately, some of the obvious mechanisms of adaptation accentuate, rather than reduce, imbalances between exploration and exploitation. Organizations can be trapped in either excessive exploration or excessive exploitation through short-term adaptive responses to experience.”

2.1 Technology Cycles and Innovation Streams

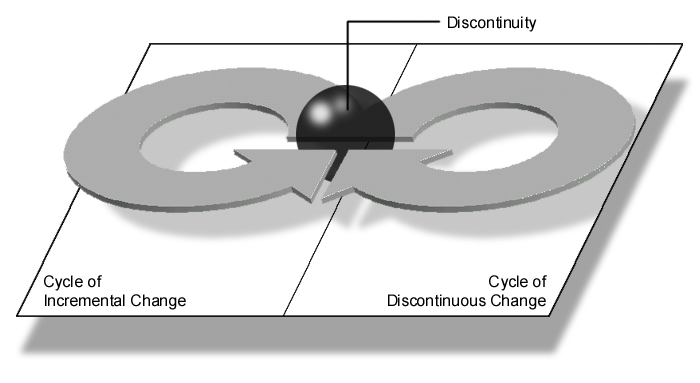

Tushman and O’Reilly (1997, pp. 25-26) frame their discussion of innovation in terms of “a pervasive phenomenon that occurs across industries: the dynamic of technology cycles and innovation streams.” Each cycle consists of three phases. Each begins with a flurry of disparate innovations as a new product or service emerges—witness Beta and VHS videotape formats. Central to each cycle is the emergence of a dominant design.2 This phase is followed by a period of “process innovation” in which refinement of the service or product occurs through incremental and architectural change. A subsequent cycle begins with a new product or service innovation. Innovation streams are the flow and interaction of these innovation-driven cycles over time. Figure 1 (freely adapted from Tushman and O’Reilly, 1997, p. 162) illustrates innovation streams.

Tushman and O’Reilly demonstrate technology cycles and innovation streams with the emergence of the automobile at the beginning of the 20th century with competition among an array of possible technology solutions for basic design and power plant. The Model T Ford established the dominant basic design (type of engine, location of the steering wheel and brake pedal, etc.) followed by a period of design and process refinement at Ford and throughout the industry.

The next technology cycle began with the introduction by General Motors of the fully-enclosed chassis in 1919. Tushman and O’Reilly (1997, p. 27) note that Ford was not prepared for the discontinuous change brought about by General Motor’s introduction of the enclosed chassis and was forced to shut down its River Rouge production facility for a period of redesign and retooling. Ford was caught off-guard as a result of its singular focus on “incremental change and increased productivity.”

Fundamental to the concept of success in Tushman and O’Reilly’s model of the ambidextrous organization is a proactive attention to the dynamics of all three phases of the cycle. And, of equal importance, long-term success depends on managing a continuous sequence of overlapping cycles within the framework of an ambidextrous organization (1997, p. 157).

2.2 General Implications for LIS

Tushman and O’Reilly note two sources of discontinuous change: (1) forces within a maturing organization, and (2) forces from the outside with responses to externally derived innovations. These two sources comport with Baum and Singh’s (pp. 9-11) two interrelated dimensions to the processes of evolution: (1) an ecological dimension that is “concerned with the mutual interactions between ecological entities at the same level of organization,” and (2) a genealogical dimension “related to the reproduction of new entities from old; the replication of routines, organizations and species.”

Historically, there have been few external forces impinging on LIS institutions that might have induced discontinuous change due to the near total occupation by a single profession of the niche defined by librarianship. The only external forces were based in competition for resources among disparate, non-competing services and not in the niche of service itself. As a result, we posit that much of the modern history of LIS has been focused on the genealogical aspects of simple propagation of the profession’s genetic material and slow, internally induced incremental change.

Harris, Hannah, and Harris (1998, p. 166) state: “F. W. Lancaster [1991, p. 4] is clearly correct when he concludes that ‘on the whole, the [library] profession has been neither imaginative [nor] innovative in its exploitation of technology.’” Even when substantial innovations that might have produced true shifts in the community of practice (e.g., the computer) made inroads into LIS institutions, the results were mostly trivial tinkerings at the margins. The community’s application of the computer targeted doing the same “old” things better as opposed to doing better “new” things. Even the introduction of digital networking resulted in only marginal innovations (e.g., improved interlibrary loan through network access to bibliographic utilities). While we do not intend to trivialize the shifts in the standards of practice brought about by these marginal innovations, they are insubstantial when compared to others currently waiting in the wings.

It was not until the recent emergence of both the World Wide Web as an information and publishing environment, and, an array of incipient competitive forces (even in the form of users striking out on their own information quests) that the LIS profession began to sense a truly discontinuous change. As noted by Van House and Sutton (1996), due to the historic isolation of its practice niche and its myopic habitus, the profession (and its practitioners and educators) may be ill equipped to deal with discontinuous change to say nothing of consciously setting out to produce such change.

The central question of this article is concerned with whether the LIS profession can be equipped to meet the challenge of being both the change agents in the processes of discontinuous change and the managers of incremental change. In the end, it is a question of whether LIS professionals can thrive in the context of punctuated equilibria. If the challenge is to be met, it will be the result of our having created learning environments that are substantially different from those we see in our professional schools today. It is to such possible learning environments that we now turn.

3. Creating Learning Environments that Promote Innovation

This article’s central question is: “How do we build learning environments that support the development of professionals able to design, implement, and manage ambidextrous organizations that provide information services and products?” To approach this question, we will define two basic dimensions of professional learning: (1) education in basic competencies necessary to practice in today’s world (legacy knowledge), and (2) education in the processes of innovation (new knowledge).

3.1 Legacy Knowledge: Propagation of the Professional Gene Pool

In exploring the propagation of the LIS profession through LIS educational institutions, we confront the Baum and Singh (1994, pp. 9-11) genealogical dimension—the passing on of the gene pool through “the reproduction of new entities from old; the replication of routines, organizations and species.” The propagation of the genetic pool of any profession is for “its knowledge base, tools, approaches, practices, and values to continue in some form”—i.e., to be passed to a subsequent generation (Van House & Sutton, p. 141). Without question, such propagation is an important function of LIS education.

It is in the context of this role of propagation, that LIS educational institutions hear demands from the LIS profession for greater levels of competency in the academy’s human products. Such demands for competency are neither unfounded nor inappropriate. Denning (1997, p. 275-276) warns of too narrow an interpretation of competency-based education stating that the term “competency” means more than just the simple demonstration of skill or craft knowledge and the ability to act on it. He states (1997, pp. 275-276): “The common theme is that competency in a field includes knowledge of its history, methods, goals, boundaries, current problems, relations to other fields, and an ability to meet or surpass standards defined by those already in the field.” Thus, “competency” defines what it takes to get to home plate and play the game as defined by the profession at any given moment in that profession’s development.

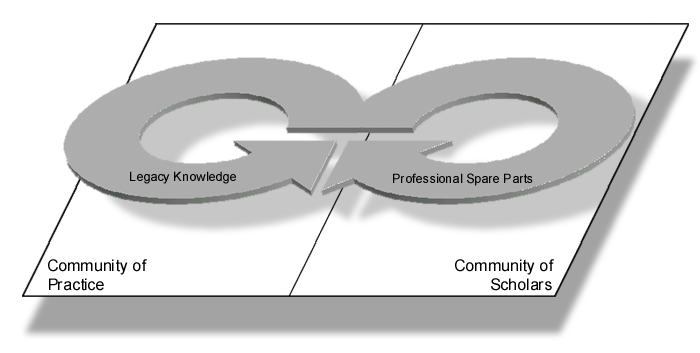

Figure 2 illustrates the cyclical relationship between the LIS community of professional practice and LIS education institutions in terms of the preparation of new professionals to fit the demands of daily practice.

Within the context of change in the LIS professional ecology, Figure 2 represents the steady-state of slow, measured change as well as the occasional, modest architectural innovation. Driven primarily by forces shaping practice within the community, tools and service models incrementally adapt. Within LIS, such incremental developments can be traced across the evolution of tools such as LCSH (both its growth and its application), Dewey, and AACR2, to name but a few. Tushman and O’Reilly (p. 167) capture the general nature of nearly a century of change in LIS professional practice in terms of the cycle denoted in Figure 2:

“During periods of incremental change, organizations require units with relatively formalized roles and responsibilities, centralized procedures, functional structures, efficiency-oriented cultures, highly engineered work processes, … and relatively homogeneous, older, and experienced human resources. These efficiency-oriented units … are often relatively large and old with highly ingrained, taken-for-granted assumptions and knowledge systems. These units are highly inertial, and often have glorious histories …. Their cultures emphasize efficiency, teamwork, and continuous improvement.”

In Figure 2, the roles of both the community and the academy complement this process of incremental change. The forge of daily practice shapes the professional community’s demands on the academy and, to the extent the academy listens, it responds through the production of human spare parts sufficiently competent to assume entry-level responsibilities within the institutions that have traditionally defined the niche of LIS.

Denning (1997, pp. 276-277) describes two “kinds of knowledge” that are useful in assessing the role of the professional academy in Figure 2. The first kind is practical knowledge of the sort just discussed with varying levels of mastery recognized by the community’s practitioners. This form of knowledge is the knowledge behind action. It is the knowledge framed in terms of professional competencies. In general, it is what Massy and Zemsky (undated) call “codified knowledge and algorithmic skills.”

The second kind of knowledge is “awareness of the observer one is.” As humans, we are filled with biases and interpretations of the world that limit our ability to see and to take action because they limit our power to “make distinctions and connections.”

“Each of us has experienced moments when our observer shifted and new actions appeared to us. . . . Unlike skill acquisition, shifts of observer can happen suddenly and can affect performance immediately. Master teachers and coaches know this: they can help the student-apprentice acquire skills and judgment faster by assessing and shifting the student’s observer at the right moment.”

Within the context of Figure 2, the traditional role of the academy with regards to this second kind of knowledge has been to shape and preserve the professional habitus of LIS. Van House and Sutton (1996, pp. 139-140), discussing the concept of habitus as defined by Bourdieu (1990), state:

“Habitus functions as a matrix of perceptions, appreciations, and actions. Habitus is the means by which a field perpetuates itself through the voluntary actions of its members. It gives the appearance of rationality and intentionality to behavior that is less than fully conscious. How individuals interpret a situation and the action they consider possible are unconsciously constrained by their habitus. Action guided by habitus has the appearance of rationality but is based not so much on reason as on socially constituted dispositions.”

When professional LIS educators and practitioners speak of inculcating in the student a controlling sense of professional mission, roles, and values, they speak of shifting the student’s “observer” in order to bring that student within the fold of the profession’s constraining habitus.

However, while a constraining habitus is fundamental to one’s professional perceptions, it becomes maladaptive behavior within the ecology when it serves to limit the power to act in the face of discontinuous change produced within or without the profession. In addition, habitus generally precludes envisioning future states which lie beyond its bounding constraints. Paraphrasing Perelman (1992), to solely frame a view of the LIS profession’s future by the roles denoted in Figure 2 is to build “a vision of the future that is glued to the rearview mirror.” It is a view that has been challenged as fundamentally flawed (see, Van House & Sutton, 1996). While the legacy knowledge of LIS (as well as its habitus) may be critical to meaningful practice today, such knowledge does little to affect the development, extension, or survival of the professional domain in a more competitive, volatile tomorrow. The future depends on innovating beyond the constraints of the existing habitus. Right or wrong, many LIS professionals view the role of passing on legacy knowledge and its controlling habitus to be the primary, if not the only, role of the professional academy.

Therefore, the fundamental dilemma is the one identified by Tushman and O’Reilly. Is it possible to develop a habitus for LIS that is capable of embracing the values of the ambidextrous organization that drives discontinuous change through innovation while accommodating the demands for stable evolution of products, services, and practices of proven value? In order to answer this question, we must look to a second cycle that drives the relationship between the community of practice and the professional academy—a cycle framed in terms of the problem domain of professional practice and the research agenda of the professional academy. It is to this little understood cycle that we now turn.

3.2 Innovative Solutions: Intractable Problems and Academic Research

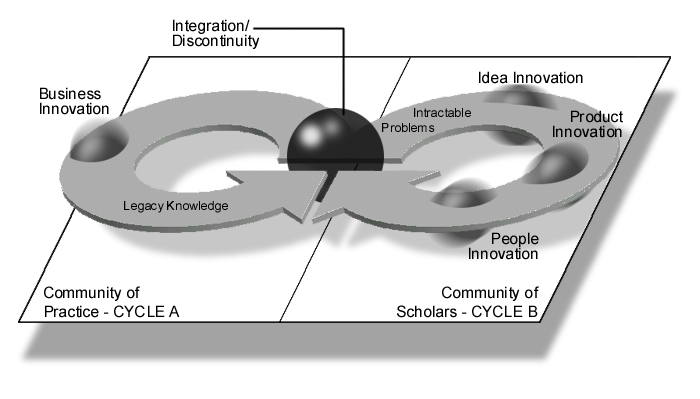

In Figure 3, we provide a statement of the ideal relationship between the context of professional practice (with its community of practice) and the research of its associated professional academy (with its community of scholars).

in Academy and Profession

At the beginning of the research cycle (denoted Cycle B), we see intractable problems stemming from the context of contemporary practice (denoted Cycle A). In this ideal relationship, these intractable problems inform research resulting in innovative solutions that flow back to the community of practice. Implicit in the Figure is our acceptance of Denning’s definition of innovation stated earlier (1996, p. 27): “An innovation is a shift in the standard practices of a community that makes them more effective at what they do.” Further, we accept the statement of Dennis Tsichritzis, Chairman of the German National Research Center for Information Technology (GMD) (Denning, 1996, p.27): “[T]he value of research lies not in the discovery of ideas but in the innovations that eventually result.” The Figure illustrates that basic research—the generation of new ideas—seldom shifts the standard practices of a community without intervention in the form of applied research. In the subsequent paragraphs, we extend the context of Cycle B by examining more closely the various research paths leading to innovation both to clarify the nature of the intervention denoted in Figure 3, and, to provide a framework for defining the role of research in professional schools.

3.2.1 Research Paths to Innovation

Within the context of the university in general and the professional academy in particular, research is the engine that drives innovation. Denning, in exploring the “new social contract for research” in the universities of the next century, holds that contemporary universities are seriously hampered by their belief that basic research—the generation of new ideas—is the only true path to innovation. Building on Tsichritzis work, Denning defines four research paths to innovation: (1) generating new ideas (Tsichritzis’ “idea innovation”), (2) generating new practices (Tsichritzis’ “people innovation”), (3) generating new products (Tsichritzis’ “product innovation”), and (4) generating new business.

Since the founding of the University of Berlin in 1809, the first of these paths (generation of new ideas) has controlled our perception of legitimate university research. As a result, it has been afforded the greatest prestige in the university. The underlying premise is that “[p]owerful new ideas shift the discourse, in turn shifting the actions of those practicing the discourse. Research consists in formulating and validating the new ideas. It places a great deal of emphasis on originality and novelty. The scientific publication process aims to certify originality and novelty through peer review.” However, Denning joins those critics that think that the original educational purpose of research in the university has been “devalued” and that the vast majority of work in pursuit of this path is mediocre, read by few, and seldom cited.

Denning and Tsichritzis’ second path to innovation (generating new practices) aligns substantially with Boyer’s scholarship of teaching (1990). “A teacher initiates people into the practices of a new discourse. Research consists of selecting, clarifying and integrating the principles relevant to the practices. It places a great deal of emphasis on understanding that produces widespread competence.” The roles of questioning, investigating, and synthesizing knowledge as well as developing the narratives by which students gain the competencies of a profession is critical to the development of new professionals capable of engaging in the processes of innovation.

Denning and Tsichritzis third path (generating new products) focuses on the application of knowledge to the development of new, innovative products and services. It is this path that provides the means to shift the standards of practice in a professional community. “New tools enable the new practices, producing an innovation; the most successful are those that enable people to produce their own innovations in their own environments. Research consists in evaluating and testing alternative ways of building a tool or defining its function. It places a great deal of emphasis on economic advantage.” Research along this path is best characterized by industry research and development initiatives and, when it occurs in the university at all, it is almost always through collaborative efforts with government and industry.

Denning’s fourth path to innovation (generating new business) relates to processes rooted in the practices of firms that “continually improve their business designs. Research consists of testing markets, listening to customers, fostering offbeat projects that explore notions defying conventional wisdom, and developing new narratives about people’s roles and identities in the world” (Denning, 1997, p. 283; Denning, 1996, p. 27). In addition to “listening to customers,” it also involves listening to the inner voice that might at times be at odds with the voice of the customer (Lester, 1998). “It places a great deal of emphasis on market identity, position, and exploring marginal practices” (Denning, 1997, p. 283; Denning, 1996, p. 27). This fourth path is the one encountered most frequently in professional practice.

Generally, universities pursue innovation along the first two paths while companies pursue the third and fourth. Universities value research in the descending order described above while companies value the opposite ordering of the paths. Denning notes that the vast majority of what is generally recognize as innovations “have come directly from the third kind of research and only indirectly from the first.”

In Figure 3, education in basic competencies necessary to practice in today’s world flows from Cycle A and becomes an integral part of educating the next generation. Education in the processes of innovation and the creation of new knowledge embodied in Cycle B incorporates three of Denning’s paths to innovation: (1) “generating new ideas,” (2) “generating new products,” and (3) “generating new practices.” The professional human products generated by Cycle B should be prepared to engage in business innovation that continually improves business designs (Denning’s fourth path to innovation).

Factors that result in failure of the dynamic flows of either cycle are maladaptive and lead to an inability to support an LIS academic environment capable of educating professionals in the dual processes of change identified by Tushman and O’Reilly. A failure of Cycle A (lack of transmission of legacy knowledge) produces a human product incapable of acting fully within the context of the existing community of practice as it engages in incremental (and occasionally architectural) change. A failure of Cycle B produces a human product incapable of effecting discontinuous change through substantial innovation or responding effectively to such change when externally produced.

There are three points of frequent failure in the Figure’s two cycles and, therefore, in the model it suggests for supporting ecologically adaptive change. There are common themes in discussions among LIS practitioners regarding the research of their academic colleagues. Among these themes are: (1) LIS academics do not understand the need for the academy to play a role in passing on legacy knowledge; (2) LIS academics are isolated from professional practice and, therefore, are unaware of real world problems and needs of the profession; and (3) as a result of the academy’s isolation, the research performed by LIS academics is viewed as irrelevant in addressing the intractable problems facing the profession. These themes may be summed up by stating that there is a perceived break between the context of community practice and academic research since the intractable problems of the profession appear not to induce research resulting in innovative solutions capable of changing the community’s standard practices. While the assertion that nobody is listening may be true frequently, the perception may also result from breaks at other points in the cycles.

In many cases, the “nobody is listening” themes stem from the academy’s myopic view of acceptable university research—particularly research in professional schools. In striving for academic legitimacy in an environment that primarily values research that focuses on the generation of new ideas (basic, curiosity-driven research) and expressly undervalues applied research (the generation of new products), the academy fosters an environment incapable of integrating the cycles. We can enumerate any number of substantial ideas generated by our colleagues in the LIS academy that failed to produce any innovation impacting standard practices of the LIS profession, or, that took an inordinate amount of time to move from idea to innovation. We posit that many such failures to produce meaningful innovations are the result of failures of the academy to embrace applied research performed entirely within the academy or in conjunction with government or the private sector.

The common result of the singular focus on the generation of ideas as the only legitimate path to innovation is the isolation of professional students from the processes of research. In most LIS programs, basic, curiosity-driven research is the domain of faculty and doctoral students—seldom is it considered the domain of the masters-level professional student. While the use of graduate assistants in some cases may temper this statement, their involvement is usually focused on clerical responsibilities, literature searches, or other similar tasks; and, their numbers are few in relation to the full population of students in professional LIS degree programs. This isolation is not mitigated by the mere presence (occasionally a required presence) of a course in research methods, design, and consumption. As a result, the masters-level professional student is effectively isolated from the processes of innovation.

Absent an active engagement of the LIS professional student in the cycle of innovation, the locus of education frequently shifts to an inordinately heavy focus on reinforcing the genetic pool through legacy knowledge. In such cases, many assert that the academy becomes nothing more than factories for professional spare parts—nothing more than trade schools. However, this is not to say that such a focus exists in all instances where the LIS educational institution has failed to engage the professional student in significant research leading to innovation. There are LIS institutions that intentionally minimize their role as transmitters of the legacy knowledge necessary to contemporary action while providing little means for active engagement in the processes of innovation leading to change.

3.2.2 Integrated Research in Professional Schools

Given Denning and Metcalf’s explication of the four paths to innovation, we now turn to a brief, and incomplete, exploration of educating for innovation in LIS. We begin by joining Denning in his assertion that tomorrow’s successful university-based professional education will consist of the integration of various paths to innovation with the curriculum in order “to teach students the investigative practices of research and the processes of innovation” and the role of those practices in a balanced view of change (1996, p. 26). We assert that a reconceptualization in LIS professional schools in terms of the presence and relationships among the types of research identified by Boyer (1990), Tsichritzis (1997), Denning (1997), and others, is not only in order, but may well determine the ultimate viability of such schools and their professional graduates.

Unlike the deck chairs on the Titanic, we do not suggest that the LIS academy simply reorder its priorities in terms of the paths to innovation. Instead, we suggest that it assume a posture that embraces all of the paths in terms of their inter-related roles in the cycle of change. And, since “[e]volutionary change is produced only by the selection of individuals, rather than the selection of demes, populations, species, or organized social groups” (Campbell, 1994, p. 24), we further suggest that tackling this problem of integration can only be achieved one student at a time. Thus, we posit, that the primary goal of the professional academy is to generate new practices that meet the needs of a changing world through immersion of the emerging professional in the processes of product innovation (informed by new ideas) and business innovation. The second goal is the transmission of legacy knowledge. Both goals support the overlapping cycles of change.

3.2.3 Possible Changes in LIS Education

It would seem that the various directions chosen that lead to integration of the paths to innovation will play pivotal roles in differentiating one successful LIS academic institution from another. While those directions will be many, in the following paragraphs, we will suggest aspects of one.

A cursory examination of nearly all the curricula of LIS schools reveals a relatively extensive use of internship experiences. In many institutions, such experiences are required for the professional degree. Historically, the apprenticeship was the mechanism by which the two kinds of knowledge noted above—practical knowledge behind acceptable professional action and the framing of the apprentice’s professional “observer” were inculcated. In the absence of professional schools, the apprenticeship was the primary instrument by which a profession’s genetic material was passed from generation to generation. As a result, internship serves the genealogical aspects of both simple propagation denoted in Figure 3 and the processes of incremental change. Internship is one context where the student exercises both the codified knowledge and algorithmic skills he or she has learned that are necessary to current practice.

A different sort of student experience is necessary to support the paths to innovation. Potentially, the clinic is such an experience. While taking small definitional liberties, the core focus of the clinical experience on problem solving remains central to our meaning. As defined here, clinic represents a student experience through which new knowledge rooted in the research experience is applied to solving an intractable professional problem. So defined, the clinical experience is not based in the profession’s legacy knowledge and experience but seeks solutions through substantial innovation. Properly structured, the clinical experience can wed the investigative practices of all of the paths to innovation while providing a laboratory for “questioning, investigating, and synthesizing knowledge.”

Isolated examples of the immersion of LIS masters-level students in the processes of product innovation can be found in many LIS institutions. For the past several years, we have worked with a number of LIS students on a federally funded project to develop new tools for organizing and accessing educational materials on the Internet. The project required that the students be actively engaged in the application of new knowledge to the development of a new solution to a systemic problem in the discovery of web-based resources. While the experience not only altered their perceptions of professional identity, it instilled the confidence and the investigative skills necessary to product and business innovation in their professional lives. We posit that these sorts of experiences should be institutionalized. However, doing so on a scale necessary to meet the needs of the full LIS student population will not be without challenge.

4. Conclusion

In this article, we have tried to demonstrate that adaptation to the environment by biological and human-made organisms must take account of the dynamics of punctuated equilibria. Using Tushman and O’Reilly’s ecological model of innovation-induced change in companies and organization, we explore the nature of the research paths to innovation in LIS academic institutions. We conclude that an as yet unattained integration of those paths will be necessary for the LIS academy and the profession to be adaptively engaged in the accelerating cycles of innovation we see on the horizon.

For some time, we have been warned that in the future, most Americans over a lifetime will be engaged in two (and sometimes many more) professional careers. We have been warned of product, knowledge, and skill obsolescence in the context of punctuated equilibria. Lying masked behind the words of CEO Platt of Hewlett Packard that “[w]e have to be willing to cannibalize what we’re doing today in order to ensure our leadership in the future” (Tushman & O’Reilly, 1997, P. 216) is the fact that for LIS to participate fully in the processes of punctuated equilibria, it must embrace the inevitable and deliberate obsolescence of extent professional knowledge and skills. While Tushman and O’Reilly’s model suggests that companies and organizations may be ambidextrous in responding effectively to either internally or externally induce discontinuities resulting from significant innovations, they have little to say of individual human consequences. Discontinuous innovations “tear at the political, structural, and cultural fabric” frequently leading to “revolutionary organizational change” (Tushman & O’Reilly, 1997, p. 222). Highly discontinuous innovations inevitably lead to new knowledge and new practices that displace the old—to cannibalize is to render obsolete. Therefore, for the individual professional, cycles of discontinuous change point to another frequently heard warning—the need for life-long learning. Lifelong learning is the individual human response to the dynamics of a model of change based in punctuated equilibria. So, the question must be asked: “How do we structure LIS educational institutions and the LIS profession to play a continuous role in re-educating the professionals whose knowledge and skills have been intentionally rendered obsolete both from within and without the profession?”

Van House and Sutton (1996, p. 145) close The Panda Syndrome: An Ecology of LIS Education with the warning: “Without a rapid response and fundamental change, LIS education is likely to go the way of the pandas: cute, well loved, coddled, and nearing extinction.” Here, we extend that warning to the LIS profession at large.

Footnotes:

- Tushman and O’Reilly (1997, p. 157) actually identify three forms of change through innovation: (1) incremental change, (2) architectural change (“innovation that reconfigures existing technology”), and (3) discontinuous change.

- The dominant design is not necessarily the superior design. See Tushman and O’Reilly, pp. 157.

References:

Abbott, Andrew D. (1988) The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baum, Joel A.C. and Singh, Jitendra V. (1994) “Organizational Hierarchies and Evolutionary Processes: Some Reflections on a Theory of Organizational Evolution,” IN Evolutionary Dynamics of Organizations, Joel Baum and Jiterdra Singh, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3-20.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1990) In Other Words: Essays toward a Reflective Sociology, Matthew Adamson, Trans. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Boyer, E.L. (1990) Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Princeton: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Campbell, Donald T. (1994) “How Individual and Face-to-Face-Group Selection Undermine Firm Selection in Organizational Evolution,” IN Evolutionary Dynamics of Organizations, Joel Baum and Jiterdra Singh, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 23-38.

Denning, Peter J. (1996) “Business Designs for the New University,” Educom Review, 31(6):21-30.

______________ (1997) “How We Will Learn,” IN Beyond Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing, eds. Peter J. Denning and Robert M. Metcalfe. New York: Springer-Vertag, pp. 267-286.

Hannan, Michael T. and G. Carroll. (1992) Dynamics of Organizational Populations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Harris, Michael H., Stan A. Hannah, and Pamela C. Harris. (1998) Into the Future: The Foundation of Library and Information Services in the Post-Industrial Era. 2nd Edition. Greenwich, CT: Ablex Publishing.

Lancaster, Frederick W. (1991) “Has technology failed us?” In Information Technology and Library Management. A. H. Helal and J. W. Weiss, eds. Essen, Germany: Universitatsbibliothek Essen.

March, James G. (1994) “The Evolution of Evolution,” IN Evolutionary Dynamics of Organizations. Joel Baum and Singh, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 39-49.

Hannan, Michael T. and John Freeman. (1989) Organizational Ecology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lester, Richard K. (1998) “Companies That Listen to Their Inner Voices,” Technology Review 101(3):54-64.

Massy, William F. and Robert Zemsky. (undated) Using Information Technology to Enhance Academic Productivity. [Online] Available: http://www.educause.edu/nlii/keydocs/massy.html.

Perelman, Lewis J. (1992) School’s Out: A Radical New Formula for the Revitilization of America’s Educational System, New York: Avon Books.

Stuart A. Sutton. (1995) Invited Paper: “Core Competencies for the Information Professions and the Evolution of Skill Sets.” Education Libraries 18(3):6-11.

Tsichritzis, Dennis. (1997) “The Dynamics of Innovation,” IN Beyond Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing, New York: Springer-Vertag, pp. 259-265.

Tushman, Michael L. and Charles A. O’Reilly III. (1996) “Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change,” California Management Review. 38(4):8-30.

______________ (1997) Charles A. Winning through Innovation: A Practical Guide to Leading Organizational Change and Renewal. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Van House, Nancy A. and Stuart A. Sutton. (1996) “The Panda Syndrome: An Ecology of LIS Education,” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science. 37(2):131-147, 1996

Wilson, Edward O. (1992) The Diversity of Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.