Sapience

George Mobus

The University of Washington Tacoma,

Institute of Technology

Part 1. An Introduction to Sapience

Part 2, The Relationships Between Sapience, Cleverness, and Affect

Part 3, The Components of Sapience

Part 4, The Neuroscience of Sapience

Part 5, The Evolution of Sapience

Preface

This should be viewed as a work of integration and synthesis rather than a report on original scientific research of my own. I will include some aspects of my own work where appropriate, but the majority of what I write about in this series of working papers is a distillation of much fine research done by many others in many related, but usually distinct disciplines. It is highly cross-disciplinary in nature and may challenge some readers to pursue more education in one or more diverse fields.

The anchor for this work, that which has provided an overall motivation for it, is I think a legitimate research question that can and should be pursued intellectually. The implications of any answer that is even close to the one I will present has extraordinary practical ramifications.

The basic question has been with me from an early age as I noticed that the world as advertised didn't seem to line up with the world as I experienced it. The question is basically this: Why, if our species is so smart and creative and rational, do we seem to make such errors of judgment when pursuing our interests and end up making things worse rather than better? I will give examples below.

The question stems from a deep interest in understanding the human psyche, how we think, and how do we make decisions. It is spurred on by the observation that so many people seem to be oblivious of the conundrum posed by my question. Most people seem to think nothing of the fact that we claim one thing for ourselves and yet actually behave in a completely different manner. Is this “doublethink” ala George Orwell? Or are our brains wired in ways that prevent us from seeing reality? Of course there is always the possibility that it is me who is out of touch with reality. So at least I would be interested in what kind of psychosis I might be suffering from!

Most of my educational efforts have been directed toward coming to grips with these issues. Even my doctoral dissertation focused on a key aspect of how the brain works (and ultimately how the mind works) in the form of how our neurons encode causal relations as a basis for controlling behavior. I used a computer to explore this avenue so I ended up with a PhD in computer science even if the framework of my research was really neurobiology. All of my questions have revolved around the key question of how does the brain work, and how well does it do its job. I spent no small amount of time studying classical artificial intelligence (AI), which led me into cognitive psychology topics. I wanted to get a better understanding of what we really meant by intelligence. So when I got my first academic job I continued the use of my learning algorithm from my dissertation work in the context of a more fully developed autonomous agent that could learn to modify its behavior when conditions in its environment changed. I built more elaborate robots with more elaborate brain-like control systems modeled after simple animal brains.

That, along with my on-going interest in matters neurobiological, led me deeper into the exploration of how the brain as a whole might work, especially understanding the issues of memory encoding and representing percepts and concepts in cortical networks. But ultimately it has led me into questions of how those encodings were used in thinking and behavior control.

All the while the psychological paradox of our supposed intelligence even while we continued to do stupid things continued to haunt me. More evidence was emerging that showed we were not the logical or rational decision makers that we had assumed we were. Indeed as the evidence grew that we were actually pretty bad at making certain kinds of judgments I began to suspect that we humans lacked something essential as we confronted increasingly complex social and technical problems. Such problems could not be solved by rational thinking alone. My experiences working on committees in academia, ostensibly working on very much less complex, local problems compared with the massive global ones provided me with a clue. Working among people who were, presumably, among the smartest in the world, but who, outside of their domain of expertise demonstrated a certain lack of critical thinking when it came to other kinds of issues, convinced me that what humans lacked, in general was not sufficient intelligence (of the logical/rational kind) but sufficient judgment. Particularly I noticed a lack of experience-based judgment, that which comes from developing what might be called a more ‘generalized’ judgment. Why I noticed this may have been due to the breadth and depth of some of my own life experiences that had covered a variety of activities and jobs.

Following that thread I found myself getting into the literature on wisdom. At first this was the general literature that included cultural views of wisdom, what it was, how you recognized it in others, and how it developed in those who embodied it. Later I found the psychological literature and was surprised to learn how advanced some of the thinking was on the issues of judgment and wisdom. And it struck me, somewhere along the way, that this is exactly what is missing in the common person. The attainment of wisdom for individuals was nearly absent in the population as a whole. The more I read about how wisdom functioned, when if functioned, the more I came to realize that the lack of this facility is what was causing our otherwise brilliant people to make such horrible decisions in so many arenas of life.

My observations of the judgment behaviors of very smart people can be explained if we posit that our culture has come to have a low regard for wisdom. Many very smart people believe that high intelligence can compensate for experience-based judgment, for wisdom. Indeed our modern western culture eschews wisdom as irrelevant in too many cases due to our obsession with youth and a notion that the past does not provide much insight into the current situations. This is reinforced by our obsession with new technologies that often seem to put older people to a disadvantage in keeping up. I have seen several young, smart people ignore the advice of their elders on the grounds that their own intellects and explicit (domain) knowledge could surely trump whatever thoughts an older person could have. Of course, if the majority of people do not possess the native facility to build wisdom over their lifetimes, no matter how intelligent they are, then most of the time the elders are not as wise as might be needed. And the younger people are not wise enough to recognize true wisdom when they hear it!

Good judgment requires several components. First one must have the native mental facilities for learning from life experiences. One must be able to intuit which experiences should be attended to, and extract the meaningful lessons from those experiences. Those experiences must be significant, life altering ones. Both joys and sorrows must provide understanding. And the brain has to integrate those experiences into the background of knowledge already attained. The lessons of experience must expand and deepen the tacit knowledge of the knower. The mental facility also means that the experiencer learn from mistakes as much as, perhaps more, from successes. Indeed the experiencer must recognize when she has made a mistake and self-honestly own up to it. This seems hard for most people to do. They frequently do not even recognize that they have made a mistake, let alone be able to learn from it.

It takes a long time to build up the kind of tacit understanding of the world and how it works from the integration of life experiences. Wisdom is often associated with age. But it also takes a brain that is able to facilitate the accumulation of tacit knowledge needed to provide the intuitions that support good judgments. Much has been written about the nature of wisdom, how one gets it, what one does with it, etc. Now there is a growing body of literature regarding the psychological aspects of wisdom, especially, it seems, as pertains to geriatrics and observations of the elder years. But very little has been done with regard to what must be going on in the brain in order to support wisdom as it develops. We have many researchers exploring what goes on in the brain that we would call intelligence or creativity or affect (and combinations of those) but almost nothing that looks at the brain systems that support wisdom development. I hope the approach here may offer impetus to that effort.

Part 1. Introduction to the Concept of Sapience

Why Haven't We Developed a More Perfect World?

If we are such a clever species, why is the world the way it is, and heading in a bad direction?Unless one has one's head buried in the sand it would be pretty hard to miss the major trends in the world that suggest that, indeed, we finally do find ourselves in that ‘hand basket’ heading to a very hot place.

In the case of our world's climate, this may be literally true. Global warming is now clearly disrupting what we humans had gotten used to as a ‘normal’ climate. We developed our agriculture/food systems based on what was normal and now it looks like the chaotic climate is going to disrupt food production. And the best science tells us that the rapid change in global average temperature is due to human use of fossil fuels in the industrial economy.

The current use of fossil fuels, which grew exponentially since the onset of the Industrial Age, is very clearly causing a global shift in climate. Many very rational people recognize the connection and call for a cessation of the use of fuels. But really how rational is this? It turns out that our whole economic system is dependent on the burning of those fuels. If we simply stopped using them, and there is no real viable replacement for the energy needs to keep the economy going, then our system would crash nearly instantly and billions of people would be left without means for producing food or obtaining water or providing shelter. How is that rational? Of course, the irrational response, coming mainly from the right side of the political spectrum, is to deny that burning fossil fuels is the cause of this conundrum.

But here is what is extremely telling about our current situation. We have actually known, that is science has provided us with the knowledge, of the effects of burning fossil fuels for many decades. Indeed some might argue that we could have worked out the consequences over a century ago. If we knew, if we understood the situation, then why did we keep doing it? We were far less dependent on fossil fuels at the end of the 18th century, basically we relied on coal for industry and whale oil for lighting. We were still much less dependent at the end of the 19th century when some scientist began to alert us to what they saw as the potential problem. We could have put the brakes on then and been more cautious in developing our reliance on fossil fuels. Why didn't we?

Even more telling, in the story of mankind's use of fossil fuels, is the very fact that we have long known that their quantities were finite. We have known for a very long time that there is just so much of the stuff in the earth and that it would one day become so difficult to extract that it would, in effect, be gone. We've known this for a very long time. We could even, if we had taken the time to test it, measure the rate at which the energetic cost of obtaining the next unit of energy was rising. We could have estimated from those measurements, along with knowledge of how much of the stuff we'd already used up, to determine when we would effectively run out as we kept increasing our use at exponential rates. The math is a little demanding, but not really that hard to do.

In fact, many people have done the math not just for fossil fuels but for a variety of resources that are either finite or constrained by finite resources. Thomas Malthus, the late 18th and early 19th century political economist readily deduced the relationship between population growth and food availability. He essentially laid out the notion of carrying capacity as a limitation on human populations. Of course, his thesis was about a principle that, ceteris paribus, would take effect to limit the human condition. He was not concerned with what would happen if technology, like the Green Revolution were to make all other things not equal. The question he left us with was: “Under what conditions would this principle ultimately obtain?” We did not really do a good job of asking that question.

Well, that isn't entirely the case. Some of us did. Paul R. and Anne Ehrlich raised concerns in The Population Bomb about what would happen if population continued to expand exponentially. Rachel Carson sounded the alarm regarding the potential dangers of unrestricted uses of pesticides in Silent Spring. Donella H. and Dennis Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III provided actually compelling evidence of what to expect from runaway growth of population and the economy (consumption of resources and production of pollutants) in The Limits to Growth. And these are really just a few examples of the very few people who have actually grasped the significance of what we humans were doing and understood there would be consequences.

And, this is the point. The vast majority of humanity, and especially the very clever beings who heard these warnings, simply did not heed the calls. The most clever of all came up with all kinds of reasons why these authors and others were just simply wrong. Rather than wisely attending to the warnings and taking caution, perhaps even calling for more investigation and testing, they simply invented rationalizations to brush those concerns aside so that the rest of humanity could get on with the business of economic growth and prosperity.

There is a stark reality rapidly asserting itself into the consciousness of all those happy consumers and wealthy bankers who failed to take notice of the potential problems. It is becoming clearer with each passing day that the Cassandras were right to varying degrees. The global climate is clearly changing in chaotic fashion. We are running out of fossil fuels and many other resources. All of the clever economists were wrong. All of the clever politicians were wrong. All of the clever citizens going about their business as usual were wrong. And now the consequences loom large and dangerous.

There are many reasons that people have been able to ignore the evidence and the legitimate reasoning of science. Or as Upton Sinclair said: “It’s hard to make a man understand something when his livelihood depends on him not understanding it.”

Very intelligent and creative minds can be usurped by deeply held emotional motivations. When someone has been imbued with beliefs that support their life history, especially their comfortable circumstances, and they do not have the wherewithal to question those beliefs (as will become clear below), then something else takes place in the mind. Rather than produce rational reasoning, they can produce rationalized reasons. They can find ways to justify their preconceptions without actually realizing they are doing so. It is done quite often at a subconscious level so as not to raise suspicions of the conscious thinker. And the remarkable thing is that to the conscious observations of the thinker, the rationalizations appear to be perfectly rational. Moreover, the motivation to do so is increased if the introduction of a contrary conception suggests a threat to their preconceptions. Denial is an extraordinarily common reaction to the implications of global warming or peak oil. There are a number of suggested evolutionary reasons why these seemingly dysfunctional mechanisms work the way they do. In some cases it can be argued that denial and rationalization might have lent fitness to our early ancestors. My own view is that it is more likely that the circumstances of life did not test these lackings as dysfunctions. They were never selected against per se. Rather another mechanism emerged that, if fully developed, could override or dampen the effects of these more emotionally motivated responses. This new feature was selected for, initially, but never reached the level of strength needed to completely reign in the dysfunctions.

As yet another example of very smart, clever people able to avoid rational thinking, the persistence of the belief in economic and population growth is spite of all the evidence to the contrary stands out as a testament to the lacking of something beyond cleverness in the majority of human minds. Read any opinion piece by renowned economists — people with PhDs — or listen to the various economic and political talking head pundits in the media, or listen to the rhetoric of the President of the United States. They all believe that the only way the economy can be healthy is if it is growing. The simple rationalization is that such an economy produces jobs and creates additional wealth — the tide that raises all boats. Somehow the fact that infinite growth in any real physical system is not even possible in principle never seems to occur to them. They manage this mental legerdemain by believing that the economy is somehow NOT a physical system. Money is not considered a physical constraint so it can grow forever. Moreover, it can generate itself. Investment in an interest bearing account will magically produce more money. What they fail to remember, it seems, is that the only way that works is if the saved money is lent out to do some real physical wealth producing work. It is easy for the mind so steeped in the belief in the growth of money to ignore inconvenient realities because something very fundamental is lacking from their mental processes that would better guide their intelligence in thinking rationally.

As a species we have also failed to learn from history to some degree. Humans have made egregious errors throughout time, too many to enumerate here. We have had wars, civilization collapses, and recurring brutalities and never seem to learn that much of it was from our own doing. Even seeming natural disasters can be aggravated by our poor judgments as when people repeatedly build homes in known flood plains or on cliffs overlooking a panoramic view when there is evidence that the cliffs might be subject to collapse. As clever a beast as we are, we are not very good at thinking about long time scales, or learning from historical experiences. Something in our brains, or rather something missing from our brains, seems to preclude capturing the wealth of knowledge from history and assembling a tacit model of how things have actually worked. Rather, our minds focus on individual stories and ‘Great Men’ theories as surrogates for that wealth of knowledge. But, of course, it isn't wealthy enough in that surrogate form. We collectively continue to repeat the same mistakes. Our so-called leaders continue to fail across a broad spectrum of decisions that could have been better informed by a greater model of how the world works based on our experience of how it has worked.

Humans have proven themselves good at complex problem solving. They have two mental facilities widely acknowledged as the source of their evolutionary success. They are intelligent in many ways and they are creative in finding new ways to do things. Intelligence and creativity have long been studied scientifically by psychologists. More recently neurobiologists and computer scientists have gotten into the field of study. This work has had some expected results. It has told us what we wanted to hear, that we are far above even our nearest relatives when it comes to intelligence and creativity. But there are also some not-so-pleasent stories to tell. It turns out that we are not as rational (in the sense of deductive logic) as we would like to believe. We are motivated, like all animals, by bodily needs and emotional drives. And it turns out that those emotions very much color our perceptions and conceptions even while we enjoy the illusion of making rational choices. Moreover, our brains don't really work like computers at all. We run on heuristics not algorithms, and those can and do produce non-veridical results in our decisions and subsequent behaviors. We are usually making mistakes. We are not quite as clever as we thought we were.

The combination of intelligence and creativity I like to think of as cleverness. Even if intelligence is not really that rational, still it works pretty well in terms of solving local-scale problems, especially where the costs of small mistakes aren't that great. It has provided our kind with incredible adaptive capabilities as we spread across the globe and invaded numerous different ecosystems. Cleverness worked out pretty well for us as long as the world was relatively simple (by comparison to today's industrial/information age). But it was that very cleverness that created the technologies and procedures that have led to the modern world and all of its complexities. This world is now so complex that ordinary clever people cannot begin to grasp it. And so we blindly follow whatever rules of conduct we are told are the right ones to keep things going.

But cleverness was not enough. As can be seen by the above examples of foolishness in not heeding the warnings of seers, we, as a species, seem to be lacking something crucial that prevents us from using our cleverness in ways that will provide for long-term stability and the affirmation of human and all life. We do not, very often or sufficiently, use our cleverness wisely. Fools rush in where wise men fear to tread. And rush we collectively have.

Wisdom is basically the ability to make sound judgments that guide our decision processes when cleverly solving problems. There seems to be ample evidence that the majority of we humans are not wise in any real meaningful way. And, ironically, it isn't just a matter of being more clever. Some of the most intelligent and creative people in history have been shown to make foolish mistakes too often to simply write off as mere ‘oops’.

My thesis is simply this. Humans evolved just enough capacity for wisdom to be successful in tribal organizations as far as living in the natural world. But at some point in our history our cleverness created a cultural environment that began to select against further development of the capacity for wisdom. Ergo, that capacity could not expand in the same way that the combination of cleverness and culture (especially technology developments) did. The latter overtook and damped down the capacity to develop wisdom in favor of some of those more basic affective drives that guide decisions from the more primitive parts of the brain. Essentially, we created a situation in which the very capacity that had gotten us to the threshold of what I call second order consciousness (conscious of being conscious — explained later) would no longer develop. In a sense it was no longer needed. Cleverness fed through the mechanics of culture would take over as the only, seemingly, needed capacity to thrive in the world.

What little native capacity for wisdom remains in our species must be very poorly distributed in the population. Every once in a while an individual with uncommon insights and good judgment emerges in the limelight, especially focused in crisis situations, and we recognize that quality of wisdom (Nelson Mandela and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi come to my mind) in their advice and decisions. To be sure, many elders display some level of wisdom in conducting their own affairs. Wisdom is historically and culturally associated with age. But also culturally, we most often discount the elderly as not having relevance to a dynamic, progressive society. They are very often shuttled off to some home for the aged and are generally treated as a kind of liability to the economy. Youth is what is favored in the capitalist economic system particularly.

Thus I claim we humans, on average, are stunted when it comes to the capacity for wisdom. That capacity must originate in the brain. It must be based on brain structures and functions that are heritable and developable just as much as is the case for intelligence and creativity. Wisdom, coming with age, is actually a manifestation of that capacity along with the acquisition of life experiences that contribute to our intuitions and judgments. Brains that have a more developed capacity can give rise to greater wisdom later in life.

I prefer to use the term sapience when referring to the capacity of the brain. I use this term because, among other aspects, our species is called Homo sapiens, “man the wise”. This binomial nomenclature designation was bestowed on us by the inventor of the systemics naming system, Carl Linnaeus who thought it best described humans. In a real sense, of course, one of the defining features of humans is their ability to make judgments on issues that have a much wider and longer-term scope than any other animal in nature. It is not likely that chimpanzees think much about what might happen next year if they do thus and so today. Humans do think about the future and ask questions about outcomes of actions taken in the present. So the basic capacity does seem to be present. We do possess a modicum of sapience, surely. But I maintain, it simply isn't enough to overcome our baser tendencies to use our cleverness for short-term gains that will cost us dearly in the long term.

From Whence Cometh Wisdom?

Intuitions and judgments come from deep within the mind, from the subconscious levels of thinking. They arise, as it were, to conscious awareness and have the role of guiding conscious decisions. The mind is doing an incredible amount of work in sorting out all of the variables and conditions that constitute a complex situation. Those men and women who seem to be able to effortlessly provide a recommendation (guidance) in complex social problems that proves to be worthwhile in the long run are noted as ‘wise’ individuals, so long as there are those who are able to recognize the advice and take it (note that in eastern cultures there is still some reverence for the elders as being wise, especially still in agrarian regions) . Most often, and this seems to be a universal characteristic, such individuals are more elderly. The wise elder is an enduring meme in our collective consciousness.

Wisdom is the capacity to make good moral judgments in complex social problems that are life supporting for the majority of a society for the longest time into the future (Sternberg, 1990). Wisdom is a behavior of individuals who are competent in learning life experiences in a manner that gives rise to veridical intuitions later in life. It must be based on a brain function and competency level that increases the likelihood of survival and reproduction of the species or it would not have become a feature of human mentation. It can be argued, from the anthropological record, that early human groups that possessed at least one very wise leader were more fit than other groups in surviving the exigencies of life. Indeed, an argument can be made that the wisdom of the older members of a tribe contributed to the group fitness and thus to the differential success of those groups. Wisdom in the ways of the world was the evolutionary basis for the success of Homo sapiens. Grandparents, the locus of wisdom, could transmit that fitness to their children and especially their grandchildren thus providing a differential reproductive success advantage to their kin group. In the late Pleistocene era, wisdom was a success strategy for early man.

As the genus Homo evolved there was a progressive orientation toward two-partner mating (or some would argue toward mild polygamous mating) as child rearing became more expensive energetically. Along with this arrangement, humans were living longer past their reproductive ages. It seems that these grandparents took an interest in their children's children (perhaps because in a monogamous or semi-monagomous relationship it is easier to trace one's progeny) and their upbringing. An interesting correlated hypothesis, the Grandmother Hypothesis postulates the continued capacity for postmenopausal women to rear youngsters led to stabilization of the family units and contributed to the success of the species.

The development of wisdom depends on the emergence and differential development of brain areas that contribute to capturing, organizing, and recall of tacit knowledge. In Part 4 of this series I will delve more deeply into the neuroscience of sapience as it pertains to the brain, and in Part 5 I will further develop the evolutionary ideas just mentioned, but also consider the future of sapience.

Psychological Constructs

To begin an explication of this hypothesis we need to start with the current understanding of the psychological theories of intelligence, creativity, wisdom, and affect. A considerable amount of work has been done regarding these various ‘constructs’[1]. A great deal of credit for the substantive work in this area should be given to Robert Sternberg who has orchestrated a very useful compendium of work that delineates both the relationships between and the differences between these constructs (Sternberg, 1990; Sternberg, 2003).

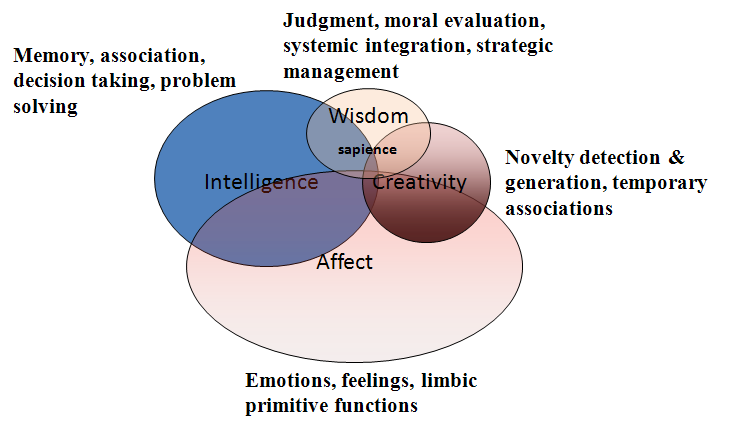

In Fig. 1 I have attempted to delineate these constructs in a kind of Venn diagram. Fundamentally, the four aspects of mental life have both individual characteristics, but also share some characteristics that account for the correlations that a number of researchers have noted in the above referenced works.

Figure 1. There are four major features or constructs to the human mind. The affect system represents the emotional and autonomic systems that we inherited from the most primitive animals (particularly reptiles). Intelligence, creativity, and more recently, wisdom are basic constructs that have been studied by psychology. Of course many other areas, such as perception, are important, but are seen as contributory to these main constructs. The relative sizes of the ovals is meant to convey the sense in which each of these constructs seem to dominate human mentation. Wisdom (sapience) is envisioned as the newest and least developed capacity of the human mind.

Wisdom shares some aspects with both intelligence and creativity (Sternberg, 2003a) as well as having an emotional aspect (Kramer, 1990). This is why I used overlapping ovals in the above post reference. All four components of mentation interact and operate together to produce the complete, normal conscious person.

In the second installment in this series I will break down the relationship between sapience and the other three constructs of mind in more detail. This overview has been meant to simply set up the framework of these relationships. Here I want to further dissect the nature of sapience to delineate it from the common concepts of intelligence and creativity and to disabuse the reader of thinking that sapience is just more of these.

Thinking

The four psychological constructs play unique but mutually interactive roles in the conscious experience of thinking. Our thoughts are shaped by the interplay between them. Actually, our conscious thoughts are, so to speak, only the tip of the cognition iceberg. Our brains carry on far more processing at a subconscious level than most of us might imagine. Since it is, by definition, subconscious, and therefore not ‘visible’ to conscious awareness, our conscious minds can be fooled into believing that the thoughts we experience come from some effortful process, especially from our intelligence. But in fact, they are now thought to emerge as perceptually or conceptually initiated structures. Indeed evidence suggests that a number of structures emerge simultaneously in various parts of the brain, e.g. areas responsible for creatively combining basic concepts in new ways or areas responsible for activating beliefs. These multiple pre-thoughts are then tested and filtered in various ways until something like a fully formed thought emerges into the limelight of conscious awareness. That thought may then be incorporated into an intentional structure such as a sentence or an action.

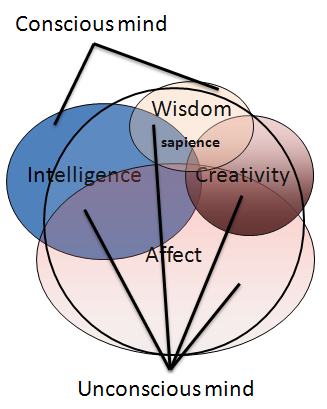

Figure 2. The conscious mind involves a relatively small proportion of our total mental activities. Here the unconscious mind forms essentially a core in which the mental activities of the four constructs operate to produce thoughts that eventually emerge into the outer conscious mind.

It now appears that the subconscious mind does an extraordinary amount of thinking. Most of this thinking is likely to be in the form of pattern recognition, matching, and categorization based on heuristic associations. If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck then it must be a duck. These thoughts emerge as intuitions or, as we will see, judgments that guide decision making. Other forms of thinking correspond with what we normally think of as logical reasoning. This is thinking that is sequential and based on what I think of as ‘tight’ heuristics. These are rules that are nearly like rational reasoning, e.g. syllogistic, or even predicate logic. They involve concepts that are essentially symbol-like (almost non-mutable), but that can be used to represent variables, and combine those symbols according to the tight heuristics such that the derivation of a conclusion is very close to what we would call sound (veridical). Almost all minds can perform the simpler forms of formal logic, but fewer have the ability to perform the higher forms. Nevertheless, the subconscious mind appears to have this facility and produces thoughts that can then be further manipulated by conscious language, as when someone is trying to think through what a logical or likely outcome of a specific action might be.

This process can be most readily seen in certain kinds of games, like chess. Master chess players use a combination of logic and pattern recognition/manipulation to decide on their moves. They examine the board and the pattern of pieces calls into their subconscious minds all similar patterns that have previously been encountered by that player. Those patterns are tagged with affective valence (see Part 2 for more explanation) as well as tacit weighting having to do with prior wins and losses. The mind then filters all of the relevant patterns as well as uses the reasoning system to make a move decision. Part of the decision is rational and part intuition or judgment.

Several authors in psychology have posited the existence of two thinking systems as just described (c.f. Sloman, 2002 for a review). They view the use of these two systems in terms of both working on a problem simultaneously and then the mind essentially resolving any differences or choosing one solution over the other. In a very real sense this is the ‘heart versus head’ conundrum that most of us experience at various times in our lives. In Part 4, The Neuroscience of Sapience, I will delve much deeper into the kinds of neural structures that might underlie these two, what we might think of as extremes, of thinking. I will argue there that I suspect the seeming dual systems of thinking is actually just the psychological observation of the two ends of a spectrum of neural processing structures that actually share some basic architectures. Combined with the conscious vs. subconscious processing, its apparent duality, this actually provides for a generally very smooth global thought processing. The same kinds of neural structures, composed of similar kinds of neurons, can simply produce more rule-like or more pattern-like processing. Indeed, in some instances it takes both working together to even represent things like the variables needed for predicate-style logic.

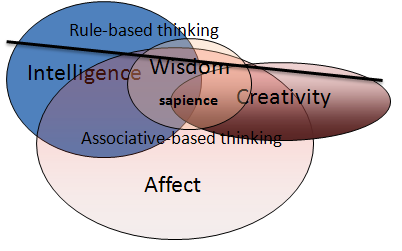

However, the twin dualities of conscious versus unconscious and logic-like versus pattern-like processing serve reasonably well in understanding some of the more mysterious aspects of the mind. Figure 3 shows a slightly different image of the four mental constructs, shifted around a little and with a line demarcating a (somewhat arbitrary) boundary between logical and pattern processing. Note that the latter occupies a much greater fraction of all of the construct areas.

Figure 3. A hypothetical division of the mind between two complementary processing systems, a logic-like system responsible for rule-based reasoning, and a pattern processing system responsible for similarity matching. The latter is shown as having a much greater amount of total mental capacity and accounts for almost all affective processing, most creativity, and a fair amount of intelligence and sapience. Logical reasoning is relegated to smaller portions of each. However, intelligence, which is what most people think of in terms of logical reasoning, carries the weight for thinking things through rationally.

The line dividing the logical (rule-based) from the pattern (associative) forms of thinking is placed to indicate that much more actual thinking takes place in the form of pattern-processing and associations than logic and rule-based inferences. Most humans, most of the time, deal with the world as they find it by pattern matching with memories of similar situations rather then thinking through the logical inferences. This is because most life situations do not require thinking through of the sequences of premises to conclusions. If we have had life experiences that encoded in our memories as meaningful situations, we will preferentially draw upon those experiences and linkages to meaningful outcomes to guide action decisions in the here and now. Besides, thinking logically requires considerably more work and time and most people have difficulty thinking through the situation when too many variables are involved (seven plus or minus two variables seems to be the average size chunks that most people can handle).

Most of our thinking is associative, and most of it takes place in the subconscious. A small smattering, then, takes place in conscious awareness and involves sequences of rules applied to propositions and variables, what most of us think of as thinking. Indeed one very plausible explanation for the conscious mind (or evolutionarily, what is consciousness for?) is that it evolved as an addendum to our ordinary supervisory functions (e.g. impulse control) specifically to orchestrate logical thinking. In fact several authors liken the conscious mind to a conductor of an orchestra. Some more elaborated supervisory functions need to selectively (and programmatically) activate specific other cognitive functions at just the right time in order to produce what we experience as conscious thinking, especially the experience of talking ourselves through a situation in our heads (silently).

I will return to this whole subject and provide some more details of how this might be accomplished in neural tissues and brain regions given what we currently understand about these. But here I would like to point out a simple fact. Though I have referred to the conscious process of thinking as a logic-like system, in fact it is highly prone to many kinds of errors. It is not fully constrained to only use a priori true premises or axioms (in math and deductive logic). Nor is it constrained to only use valid inference rules. Indeed we invented mathematics and formal logics, done by writing the symbols and rules down in an external representation, precisely because our brains have greater or lesser degrees of competence when trying to think through more complex problems and situations. Unfortunately, the formal systems we invented don't scale to most real life situations and complexities. For that we humans rely on other mechanisms to convey patterns that can be combined and manipulated (as I inferred above) in what we call stories or narratives. These, some of universal experience, can be combined and recombined in ways to produce new, interesting stories. Our fictional prose and poetry reflect our attempts to capture almost-rule-like, language-based patterns that can be shared around, not just for entertainment, but to teach lessons and educate the young. Such story construction, involving all parts of the cognitive constructs, are examples of how the supposed two systems cooperate to produce hybrid thoughts, neither purely logical nor purely associative.

The Components of Sapience

I would now like to start deconstructing the functions of sapience in the cognitive framework established above. In this introduction I will outline the components of sapience that seem the most salient at present. In Part 2 I will expand on this theme paying particular attention to the interrelationships between the components so that we understand how they interoperate to produce human thinking and consciousness. In Part 3 I will delve even deeper into each component, as it were peeling the layers of the onion to reveal more detail.

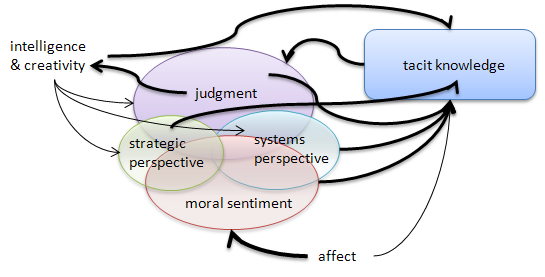

In a manner similar to the diagram of the mind introduced above in Figure 1, Figure 4 below shows a diagram of the components of sapience. The four components are judgment, moral sentiment, strategic perspective (thinking), and systems perspective (thinking). Each will be described briefly along with their relationships to the other mental components of intelligence, creativity, and affect. In the figure they are shown overlapping because they all interrelate to one another in very complex ways in exactly the same way that intelligence, creativity, affect, and sapience interrelate.

Figure 4. Sapience decomposed into four basic functions, judgment, moral sentiment, strategic perspective, and systems perspective.

The arrows, from and to external functions, in the figure are meant to roughly represent the recurrent messages that pass between functions (and presumably between brain centers that are involved in processing them). The overlapping of central functions in sapience means to convey the tight integration of these functions without explicitly representing it with arrows. Note the thick arrow from judgment to intelligence & creativity. This is meant to convey the effect judgment has on these processes (see below).

Note also the box labeled ‘tacit knowledge’. This is the storehouse of implicit memory encodings that connect conceptual memories in functional ways. It is, in effect, our model (or models) of how the world works. All of the functions of mind (intelligence & creativity - I&C - and affect) and all of the functions of sapience affect tacit knowledge. I&C act to form concepts and their relations and link them to the tacit knowledge store. Affect tags each such linkage with valence (good or bad affect; Damasio, 1994).

Judgment informs what new knowledge should be incorporated and how it should be integrated into our existing tacit storehouse. Similarly, strategic and systems perspectives help guide this process (knowledge acquisition) as well as helping interpret stored strategic and systems knowledge for the judgment function. Finally, moral sentiment, our sense of rightness and wrongness, guide the integration with respect to our social mores and rules of conduct.

Judgment

The capacity for judgment has started to come under the study of psychology and neuroscience in recent years. Judgment is one of those ineffable capacities that seems somehow related to intuition and yet clearly is linked with rational thinking and decision making. On the one hand, our judgments come unbidden from somewhere in our minds to guide our decisions, yet most of us do not really have a conscious experience of forming a judgment (Hogarth, 1980, see esp. page 1). It is just something we all do.

Judgment is an integral part of decision making. In Part 2 of this series of papers I will delve more deeply into that relationship and show how the mechanics of decision making, a function of intelligence, is mediated and shaped by judgment. For now note that we make judgments about almost everything without really thinking about it. More primitive minds are guided in decision making (presumably without conscious thought, or at least a language) more by affective drives than by intelligent reasoning, and those drives are built-in. I refer here to the primitive reptilian brain which is reactive to environmental cues that trigger emotion-like responses. The classic fight-or-flight response is a good example. In those minds there is no higher consideration of the circumstances or overriding of the initial response because there is no higher brain functions to evaluate the ‘real’ situation or broader context of the cues. The affective modulation of decision processing had worked very well through the evolution of the reptiles. The evolutionary hardwiring of responses to cues based upon temporally immediate survival considerations was sufficient as a control for behavior. We humans (and all mammals) have inherited this basic judgment system. And, all too often, it can take the upper hand in modulating our more rational sides, as when you lose your temper and behave badly as a result.

Human minds have an added advantage in being able to bring more complex learned knowledge to bear on decisions even when we are not consciously trying to do so. That does not mean we are completely rational in our choices. Quite to the contrary the system of acquiring tacit knowledge and bringing it to bear in judgments guiding decision making is far from perfect, as we will see. Our brains have many built-in biases that keep us from making completely rational decisions (see: Gilovich et al, 2002). And, indeed, it seems that most humans tend to rely more on their affective system guidance in most day-to-day or ordinary sorts of decision problems (like what socks to wear) than the experience-based approach. The reason is actually quite rational in the sense of saving time and energy. Most of the time our affective inputs to simple decisions work reasonably well. In a simpler world, where our major concerns involved conspecifics (both us and them) and nature (predators and prey) the kinds of judgments we needed to make were relatively simple. They needed lots of tacit knowledge, to be sure, but were about things that could readily be learned and understood in our model of the world. But as the world changes more rapidly and gets more complex our native judgment capacities are being put to the test. As Robin Hogarth puts it (1980):

However, the increasing interdependency and complexity of modern life means that judgment now has to be exercised on matters with more important consequences than was ever the case in the past. Moreover, the frequency with which people are called upon to make important judgments in unfamiliar circumstances is growing.The modern world is putting our capacity to build an adequate storehouse of tacit knowledge and our capacity to make critical judgments from whatever knowledge we are able to obtain to the test, most severely.

Complex problems and the decisions needed to solve them require more effort and time. The brain has to kick into a mode of decision making that requires more rigorous thinking, both conscious and subconscious. Thus it is not unreasonable that we relegate much of our everyday decision processing to guidance from the limbic system and the paleocortical brain[2] more than from the neocortical brain (See Part 4). As we will see the circuits for affective and more primitive experiential (e.g. routine patterns stored in the paleocortex) inputs to decisions are already in place and a very rapid activation of those circuits is all that is needed to produce reasonable decisions. But when the problems are really complex and convoluted, emotions, feelings and simple patterns cannot provide adequate guidance. That is where tacit knowledge comes into the picture. That is where sapience takes an upper hand, sometimes needing to down modulate the affective inputs, sometimes overriding them entirely.

Good judgment is necessary for good decisions. The more complex a problem, especially social problems, the larger the scale of involvement. More factors are involved. More people will be affected. More time will be needed. One has to think about the future and what impact the current actions will have on that future. The scope of space and time is much greater and the possible variations are literally too numerous to work through in a purely logical sense. Such problems have a more ‘global’ scale of impact and that poses a serious problem for judgment.

The reason is relatively simple. Every problem is composed of a network of sub-problems that all affect one another (see below on Systems Perspective). Yet the conscious mind must focus on one local problem at a time. If all that is brought to bear on decisions regarding that local problem is intelligence (and a smattering of creativity) there will be a tendency to try to find what we call a ‘local optimum’ solution. The reason is that we typically only have local explicit information to use in forming a decision about what to do. That local information will not include the fact that just around the next bend, out of our local (i.e., conscious) view, is an obstacle or a precipice — other related sub-problems that might be made worse by solving the current problem for its optimum. We are forced to make decisions using our intelligence and the best local information we can muster. But it does not guarantee us that we are making the right decision in a global sense. In fact there are many examples of how solving a local sub-problem for an optimum will make the global problem much worse. Tacit knowledge, if it is relatively complete and relatively valid (if our models of the whole is good) can then come into play subconsciously to alter or shape the intelligent decision making to override local optimization if there is a chance of lowering the global optimization of the larger problem.

Hence, we higher mammals, and especially humans, have brains that allow us to build a storehouse of global knowledge over our lives (if we survive!) and use that to guide intelligence in making that decision based on local information. Fortunately many decision points have characteristics of situations we have seen in the past. As such we can apply our implicit knowledge, gained in the past, to anticipate the results of a current decision. Even this does not guarantee an absolutely correct decision. But it is better than only using local information alone. There is a category of computational algorithms that mimic this concept somewhat called dynamic programming. The basic idea is to build a table of prior decisions that were successful on the chance that the same decision point may be encountered later in the computation. Then rather than solve the decision again, the algorithm simply looks in the table to extract the solution. This is a major time saver in many kinds of decision problems (and a kind of machine learning). Unfortunately computers are constrained to working on only a small piece of information at a time whereas the brain can do a massively parallel search for the needed information (See Part 4).

The more comprehensive a model (tacit knowledge) we have the more likely our decisions will prove adequate. Comprehensive here means covering a larger scope of space and a longer time scale. The more and varied life experiences we have had and the more lessons we have learned about those experiences the more power we bring to bear on the present local situation. This is why the brightest people who have lived long seem to be the wisest in general. They have brains capable of storing large knowledge sets with reliable and ready access to memories. They have in their age lived long and experienced more than average. And those experiences and their meanings are encoded in tacit form. It gets back to brain competency. The brain of someone who has a higher level of sapience has the competency to acquire the right kinds of tacit knowledge and has the competency to use that knowledge to maximize the likelihood of making good decisions in a complex, fast moving world.

Another critical aspect to sapient judgment is the capacity to judge one's own judgments. One of the attributes of wisdom seems to be the capacity for a wise person to not pass judgments on some issues when their tacit knowledge does not include experiences that apply. In other words, a wise person knows when they do not know enough to offer a judgment (which has the form of an opinion). They, like everyone else, could still rely on the built in heuristic models (Part 3 will offer details of how this works) and form opinions on these subjects. But their sapience includes the capability to recognize their own limitations and can prevent or override an urge to offer an opinion even when one has no real, efficacious tacit knowledge with which to form such opinions.

All ‘merely’ (nominally) sapient humans are strongly motivated to construct explanations about happenings in the world, even when they do not have adequate information with which to do so. They construct these explanations anyway as forms of casual or informal hypotheses with the possibility that gaining additional information might allow them to refine or modify their tentative explanation in the future. This is actually a part of the building process for gaining tacit knowledge. But it can work against most people when they do not recognize that their tentative hypotheses are just that. When they, instead, fail to recognize that they do not really have the tacit knowledge needed to form more sound judgments, they offer up opinions anyway! One can witness this phenomenon most starkly in people who hold nominal leadership positions in organizations or society. Their own self-image as well as the expectations of their ‘followers’, puts pressure on them to have the answers. Yet, and especially in a culture that values youth, they tend not to have the tacit knowledge to form efficacious judgments. Even so they are compelled to form an opinion. The followers can only hope that either the leader is uncommonly brilliant and can apply rational logic using explicit knowledge or gets lucky and guesses a good solution. But they cannot count on the leader being wise.

Moral sentiment

Altruism evolved in social mammals (and birds) as a means of increasing the fitness of the group over that of individuals (Sober & Wilson, 1994) and the general fitness of the species. We evolved a sense of right and wrong behavior in ourselves and others. The specifics of many practices and social mores vary from culture to culture, but all cultures have rules of behavior that reflect the inner sense of moral and ethical sentiments. Moral sentiment appears to be a universal property of human cognition.

While many religious and conservative people believe that moral reasoning (the 'axioms' and rules) comes from a higher power, the scientific evidence that our brains are hardwired by evolution to base judgments on inherent, and subconscious, moral sentiments is now solid.

The drive to moral reasoning is built into us as social creatures who need to cooperate more than compete within our tribe. Higher moral sentiments provide guidance to our acquisition and use of tacit knowledge and our modulation of the limbic system's automatic responses to prevent unreasoned actions. We have the ability to inhibit our tendency to get even with someone who has hurt us. We have the ability to inhibit our tendency to want to bed the first beauty we could otherwise seduce. Higher sapience means that we will exercise this control over our primitive urges. Moral sentiment and higher judgment work together to produce that which we think of as a significant difference between ourselves and mere animals.

There is another, perhaps even more important, aspect of moral sentiment that needs to be mentioned. Moral sentiment is driven primarily from the affective component of the mind. And one of the most powerful aspects of affect is love (hate is potentially even more powerful, but only for the lower sapient mind). That is, the human sentiment to cherish other beings in various ways, as mates, as offspring, as neighbors and friends, etc. is one of the most important factors in social organization and the sense of moral motivation. When all is right with the world, we love one another. This attractive force runs deeper in sapience than is generally appreciated. It is not just gushing emotion. It is a real basis for caring and thus motivation for thinking about the good for all. Wise persons, throughout history, have often been described as loving their constituents.

Systems Perspective

One of the main problems with a notion of higher sapience being dependent on more brain power in acquiring massive amounts of knowledge is that the brain is, after all, limited in its ability to encode memories. However, the memory capacity of the brain depends on how the knowledge is encoded. We now know that our memories are not simple recordings of happenings or images. Rather the brain builds conceptual hierarchical codes to represent things, relationships, movements, and so on. The brain re-uses representations through complex neural networks which allow sharing low level features among many higher-level concepts. The brain also organizes concepts in a hierarchical classification scheme that allows ready associations. For example our hierarchy of 'mammal-dog-fido' associated with 'dog-pet-fido' allows us to relate other kinds of dog-like animals and compare features, such as 'mammal-wolf-teeth-aggressive' with 'mammal-dog-teeth-friendly(mostly)'.

It is the organization of concepts into networked hierarchies that allow us to not have to store every little detail with every instance of a thing, place, or action. Rather, we now know that our brains reconstruct memories from cues by activating a specific network of associated neural clusters. The brain is designed to store massive amounts of encoded 'engrams' but only because it knows how to organize the components in such a way that many engrams can share sub-circuits.

There is another trick to organizing knowledge to achieve maximum compression. That is to base the organization of knowledge on universal models that pertain to all aspects of life. The most general such model is systemness, or the nature of general systems. No matter how complex the world seems, it is resolvable into a hierarchy of systems within systems. That is everything is a system and a sub-system of some larger meta-system. Systems have universal properties even though their forms may seem significantly different. Some systems with fuzzy boundaries may not even be readily recognizable. Yet the world, indeed the universe, is organized as systems within systems with varying degrees of inter connectivity, complexity, and organization. Some systems are too small to be detected with the normal human senses (bacteria and single-celled organisms). Some systems are too huge to be readily detected (the galaxy) by ordinary sensory means. Some systems are so diffuse that they cannot be easily categorized as a system (the atmosphere). But as long as there are aggregates of matter and flows of energy there are systems. As an aside, if this were not true, then science could not work as it does!

The mammalian brain is wired so as to perceive and conceive of the world as systems of systems. That is to say, our perceptual systems are genetically organized so as to detect boundaries, coherencies, patterns of interactions and connectedness, and many other attributes of systemness. We see things and we see those things interact in causal ways. We literally can't help it. This built-in capacity is the basis for learning how the world works. Above I alluded to the idea that tacit knowledge was a form of model (or models) of how the world works. And here I claim that the encoding of tacit knowledge begins with the grasp of systems.

To see things as systems and to recognize things interacting with one another in causal ways is, however, not enough for what I am calling a systems perspective. All animals to greater or lesser degrees have the ability to encode systemness (see Part 4). Humans have the added ability to compose models of their world using systemness as a guide to construction of those models in memory. This affords us an ability to play ‘What-if’ games or test possible outcomes by altering some variables and running the models in fast forward. In other words we can think about the future. Even so, as remarkable as this ability might be, most people do it more or less without conscious recognition. It is so natural to do we rarely even consider how marvelous a facility it is.

Sapience goes a step further. It involves thinking about thinking about the future, but also it involves thinking about systemness itself. In other words, higher sapience involves more comprehensive systems thinking. This comes out in several ways. One of the first and most important is the natural tendency to ask questions such as what larger system is this sub-system a part? Effectively sapience drives us to want to understand the context of what we perceive in the immediate arena of interest. Or, we ask what are the sub-systems inside this system (of interest) that make it work the way it does? Curiosity and a willingness to probe deeper or outward are necessary ingredients to support increasing one's tacit knowledge. The sapient person has the formula for how to answer these questions by following the properties of systemness. They know what they are looking for in terms of roles to be played in a systems organization and dynamics even if they don't know in advance what the specific ‘thing’ looks like.

The capacity to quickly organize new information on the basis of systemic principles is what allows some people to learn completely new cultures, jobs, or even careers. They can relate the specifics of a newly encountered system to the general principles of systemness and learn to manipulate the new system based on those principles applying. It is a strong perspective of systemness that allows some people, and especially the more sapient, to build a comprehensive storehouse of tacit knowledge and later to use that knowledge to rapidly adapt to new system particulars. Systems recognition and perspective is at the base of the aphorism "There is nothing new under the sun." Or the expression that "No matter how much things change, they stay the same."

Wisdom is often characterized by a person's ability to deal with ambiguity and uncertainty. This ability is greatly enhanced by the systems perspective. It permits one to be calm in the face of uncertainty, for example, knowing that systems dynamics may seem chaotic (in the vernacular sense) but are really part of the probabilistic nature of the cosmos. Systems thinking gives resolve to the notion that while there may be great ambiguity now, further investigation (gaining additional information) will reduce ambiguity since the systems principles hold universally. In other words, this is the source of faith for the wise. The world will become clear in time!

Strategic Perspective

You may have noticed that the world is forever changing. Systems thinking helps one adapt to change by providing generic templates of systemness that can be used as scaffolding for learning new things. But if one is to do better than simply react to change and hope to adapt then one has to employ a more advanced form of thinking — strategic thinking. As with systems thinking most people are able to do some strategic thinking, at least from time to time. But the vast majority of people stick to logistical and tactical decision making which is why our species has a tendency to discount the future and make near-term decisions on profitability. Strategic thinking is the most advanced form of thinking about the future (mentioned above). It is more than just playing what-if games. It also involves incorporating important global objectives into the models and deriving plans that will be used to drive tactical and logistical thinking into the future. Strategic thinking involves developing a vision of what the future world will be like and then picturing yourself (or your group) integrated into that future world in a way that is both satisfying and sustainable.

The importance of strategic thinking as an individual capacity is just beginning to dawn on some psychologists and evolutionary psychologists. So there isn't yet a large body of literature on this. What exists comes, again, from the judgment literature where people have been studying the systemic biases in human judgment that prevent people from thinking long-term, especially subconsciously. But it should be clear that a wise person is concerned with what will happen in the long run. A wise person will counsel for actions today that will have a positive impact on the future even when he or she will not be a part of that future. Average humans are relatively short-sighted. They cannot really imagine what the distant tomorrow will bring. Or they cannot envision what they need to do in order to fit into that distant tomorrow.

My suspicion is that our species was just starting to evolve higher capacities for strategic thinking (which explains why we even know what strategic thinking is!) as an advancement of our evolving sapience. But with the advent of technology, and especially agriculture, the selection pressures that would have moved us further in that direction were removed. The result is that the vast majority of people do not think very strategically, even about their own lives let alone the lives of their fellow beings and the lives of future generations.

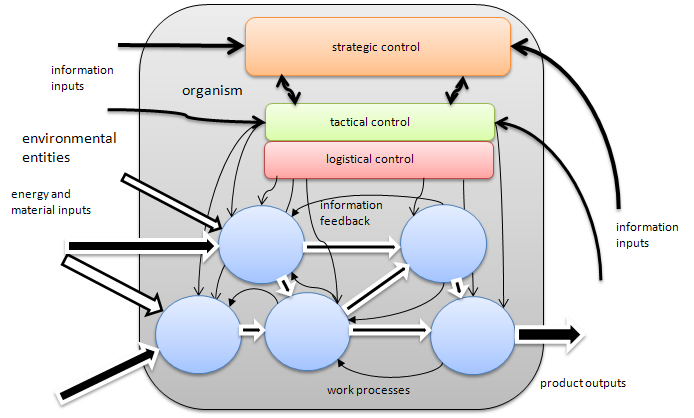

In Part 4, The Neuroscience of Sapience, I will describe the model of the brain that I think best describes the nature of human thinking and accounts for the functions of sapience. Specifically I will show how the hierarchical cybernetic model[3] describes brain architecture and functions as are being elucidated by neuroscience. Briefly, the hierarchical cybernetic model is a description of the management of a complex system based on operational level controls (e.g. the feedback controls used to regulate low-level work processes), logistical level coordination (e.g. the coordination of many operational subsystems and distribution of resources in order to optimize the global behavior of a complex system), tactical level coordination (essentially equivalent to logistical level but focused on coordination with external systems so as to obtain needed resources and avoid external threats), and, finally, strategic level management (as just described above). The human brain is a management and control system that regulates our bodies, our behaviors relative to the external environment, and, even if only weakly, our future.

Figure 5. The brain is a hierarchical cybernetic system that mirrors some of our organizational governance systems. Low level work processes need to get resource inputs from environmental entities. They interact internally by doing work on those resources and passing the intermediate products on to the next process in the system. Certain sub-systems (processes) are tasked with expelling the products (or waste products) out to the environment. This level in the hierarchy requires some feedback cooperative control (arrows with solid heads) but ultimately needs a higher, more integrated level of coordination control from a logistical coordinator that monitors the operations (not shown to avoid clutter) and provides directives to processes to assure the optimal distribution of resources. At the same basic level, the tactical coordinator monitors the immediate external world in order to coordinate the activities of the input and output processors with the availability of resources and product sinks. Monitoring the larger world, including entities not directly involved in input/output, is the strategic manager (actually a planner). This level of management also monitors the coordination levels and then provides goals and plans to that level. The time scale for activities of each level is greater as you go up the hierarchy from operations.

My central claim is that the hierarchical cybernetic theory best explains the current situation with respect to brain functions that give rise to human psychology and behavior. The strategic level of self-management was the most recent capability to emerge and constitutes a deep integral part of sapience. Sapience and the resultant wisdom that might obtain therefrom are ultimately dependent on strategic thinking but not just for the individual. Rather, the whole move toward group success relied on the strategic perspective of the group leader(s), the wise elders, who thought ahead for the good of the whole group. I will revisit this in Part 5, The Evolution of Sapience.

Other Psychological Attributes Associated with Wisdom

The psychological literature on wisdom is full of descriptions of attributes most strongly associated with wisdom, but that do not seem to neatly fit into functional categories. Wise people are often described as having contentment, calmness, peace of mind, and so on, even in the face of stresses and turmoil in their world. The ability to live with ambiguity and uncertainty without becoming anxious is also often noted. And, perhaps most important, wise people have an ability to know when they don't know. That is they are aware of their own knowledge limitations and do not attempt to offer opinions regarding issues for which they have no basic understanding.

I would argue that the latter quality is still one of judgment. As I will discuss in Part 3, we make second-order judgments subconsciously about the quality of our first-order judgments. This is especially important in judging, for example, the strength of evidence that our minds can bring to bear on an opinion (Griffin & Tversky, 2002). Less wise people tend to be overly confident in their own judgments and this is compounded by an inability to recognize their mistakes and learn from them.

The feelings of contentment in the face of adversity, however, would not seem to be recognized as a function of judgment on first blush. But as I will argue in Part 3 when we look at the components of sapience, what I call the judgment processor provides inputs down to the affect system, which includes damping down the outputs of the fear/anxiety processes (also see Part 4, The Neuroscience of Sapience in which I discuss the relationship between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala where such emotions are triggered.) Thus I think many of the attributes that are often ascribe to wise people, having to do with a sense of calmness and even satisfaction with the world as it is found are the result of the relationship between sapience and affect (implied by the overlap in Fig. 1).

It should be no surprise that as one acquires greater wisdom a certain quality of serenity also attends. The systems perspective provides an overall or holistic picture of the workings of the world and with that a sense of the dynamics following a natural course. Even when that course is negative or threatening, the wise person can often take solace in the idea that evolution is unfolding as it should and must. And with the long view of strategic perspective, one can accept the unfolding events as natural. This seeming acquiescence to negative forces may seem to the less wise, especially the young, as a kind of abrogation of caring about what happens. They would ‘fight the good fight’ to overcome any challenge. They might think the elders have just grown too tired to fight and have given up. But the wise elder can recognize the inevitable. They may council against the fight, depending on the circumstances, or they might be content to let the young carry on the fight even when they suspect they will lose. The wise person will have a good sense of when it doesn't hurt to try! With wisdom comes acceptance of the way the world is. If there is an opportunity to make the world a little different such that everyone and everything is better off, so much the better.

Summary

Sapience is the brain basis for what is unique in human cognition. It is significantly evolved in the current human species and demonstrably produces very important executive functions in this species. It is the basis for the development of whatever capacity for wisdom we see in humans. Wisdom develops over the life of an individual as a result of sapience functions obtaining tacit knowledge and using that knowledge to form moral, strategic, and systemic judgments.

Sapience is an inherent, that is genetically mediated, capacity of brains that have greater processing power in key regions of the prefrontal cortex (Part 4). However, it is not sufficiently well developed in the vast majority of the population, which could explain why humanity is in the mess it is in today. We've made some very unwise choices throughout history. We continue to fail to learn from our past mistakes, both individually and collectively. Our lack of wisdom on both fronts will doom us to make more serious errors in the future. It could possibly lead to the extinction of the genus Homo as there are no other representatives of the only talking ape, sapiens.

This has been a basic overview of the thesis on sapience. In Part 2 I will begin to delve much deeper into the relationships between sapience and the other constructs that have been studied most heavily by psychology and neuroscience, intelligence, creativity, and affect. This will, hopefully, establish sapience as a real and separate construct (as wisdom) that might be explored by those sciences in its own light. Part 3 will further develop the concepts described here as the components of sapience, judgment, moral sentiment, systems perspective, and strategic perspective. I will attempt to show how these components are derived from general psychological and neurological knowledge. Then, in Part 4 I will explore the specific neurological basis for my claims regarding the nature of sapience. There I will attempt to bring together some of the most recent research on neuroscience, with my own theoretical work on intelligence, creativity, affect, and sapience as it may be realized in actual brain structures and tissues. Finally, in Part 5 I will explore the genetic, developmental, and evolutionary significance of sapience. This will include looking backward at how sapience evolved as a unique human capacity, how it became stunted by cultural evolutionary forces, and then observe some speculations about what might be in the future. This latter subject is motivated by the concern that modern humans are, in fact, inadequately sapient for the very world we have created from our own cleverness. Human beings will need to evolve a greater sapience in order to have a wiser species if there is to be a human presence in the far future of the Earth.

Footnotes

[1] The term “construct” refers to a set of attributes and functions which can be defined and measured (to some extent) through psychological testing. Other kinds of constructs include personality profiles, thinking styles, etc. I am using the term to index the categories of specific cognitive and affective functions most related to the wisdom. It may be that my use of the term stretches its ordinary psychological meaning. If so I apologize to psychologists who might take issue.[3] “Cybernetics” is the science of control theory. The term ‘control’ carries some unwanted baggage in general parlance, where it can mean ‘command and control’ in a very top-down manner. Hierarchical cybernetics is a model that is applicable to complex, autonomous entities like people or organizations. Modern concepts of such entities cause many people to eschew the word control as having a negative connotation. Therefore I choose to use the term cybernetics to help assuage any preconceived notions about what this model has to say. A preferred alternate terminology includes coordination, cooperation, and management.

References

Note on references: This is not yet what one might call a traditional scholarly work. The references cited in the body and the list below are selected because they summarize the main points and are generally accessible to anyone with a modicum of science education. I do not quote the primary research, but references to it may be found in these authoritative sources.

- Damasio, Antonio R., (1994). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, G.P. Putnum's Sons, New York.

- Gilovich, T., Griffin, D. & Kahneman, D. (eds) (2002). Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Griffin, Dale & Tversky, Amos (2002). “The Weighing of Evidence and the Determinants of Confidence”, in Gilovitch, et al (2002), pages 230-249.

- Hogarth, Robin (1980). Judgement and Choice, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Kramer, Deirdre A., "Conceptualizing wisdom: the primacy of affect-cognition relations", in Sternberg, Robert J. (ed.) (1990). Wisdom: Its Nature, Origins, and Development, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Sloman, Steven A. (2002). “Two Systems of Reasoning”, in Gilovich, T., Griffin, D., & Kahneman, D. (eds), Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Sober, Elliott & Wilson, David Sloan (1998). Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

- Sternberg, Robert J. (ed.) (1990). Wisdom: Its Nature, Origins, and Development, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Sternberg, Robert J. (2003). Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Sternberg, Robert J., "Wisdom and its relations to intelligence and creativity", in Sternberg, Robert J. (ed.) (1990a). Wisdom: Its Nature, Origins, and Development, Cambridge University Press, New York.