By Ellen Kuwana

Neuroscience for Kids Staff Writer

October 7, 2004

Dr. Richard Axel

Image courtesy of Howard Hughes Medical

Institute |

Dr. Linda Buck

Image courtesy of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research

Center |

Usually when the phone rings in the wee hours of the morning, it's bad

news. Not so when the Nobel Prize Committee in Sweden makes their

congratulatory phone calls. Researchers Richard

Axel, MD, a professor at Columbia University (New York, NY) and Linda

Buck, PhD, a professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

(Seattle, WA) each received a wake-up call on October 4, 2004. Their

groundbreaking research about the genes involved in the sense of smell

-- and how that information is transmitted to and translated in the brain

-- is being honored with the 2004 Nobel Prize in

Physiology or Medicine. The prestigious award, the highest honor a

scientist can receive, comes with a $1.3 million check that will be split

between Dr. Axel and Dr. Buck.

Axel and Buck tackled an area of research in which little was known

previously: how the sense of smell, or olfaction, works. The

numbers generated from their work speak for themselves. There are more

than 1,000 different genes involved in the sense of smell; this, then, is

the largest gene family known in the human genome. This represents 3% of

the human genome, demonstrating how vital our sense of smell is to our

survival; we need to detect food and discern if it's still edible (not

rotten or poisonous), for example. Most animals use smell to find food,

avoid predators and interpret their environment.

|

The two researchers share a common past: Dr. Buck did her

post-doctoral

work in Dr. Axel's lab in the early 1990s. Both researchers are Howard

Hughes Medical Institute investigators, an honor that recognizes their

innovative research with financial support.

The long path to becoming a research neuroscientist:

- K-12 education

- College degree (4 years)

- Graduate school/research for Ph.D. (anywhere from 3-7 years) or

medical school for an M.D. (4 years)

- Post-doctoral work (1-6 years in an established scientist's lab; some

researchers complete one or more "postdocs."

- Job hunt

|

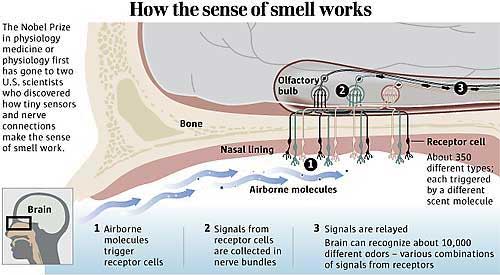

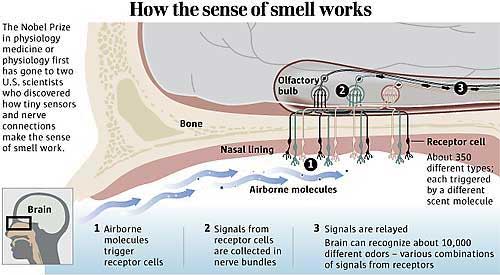

The sense of smell results from a complex interplay between the nose and a

part of the brain near the front called the olfactory bulbs. Within the

skin (epithelium) inside the nose - are you sitting down? - are up to

12 million olfactory receptor neurons; each neuron sends

a single dendrite to the epithelium. The dendrite houses 5-20 hair-like

projections, called cilia, that contact the mucus. The cilia contain the

odorant receptors. The other part of the neuron sends a single axon through the bony plate above the nasal cavity to the

olfactory bulb.

projections, called cilia, that contact the mucus. The cilia contain the

odorant receptors. The other part of the neuron sends a single axon through the bony plate above the nasal cavity to the

olfactory bulb.

Once an odor is detected, an electrical signal travels along the neuron

straight to the olfactory bulb in the brain. From the olfactory bulb,

which is like the switchboard for smell information in the brain, the

information is routed to other parts of the brain, including limbic areas. The sense of smell, therefore, is

linked strongly to memories and emotion. By using chemicals in the lab to

trace the pathways involved in smell, the researchers have been able to

map how certain smells trigger the olfactory receptors, and how the

information is conveyed by neuronal signals to the olfactory bulb and on

to other parts of the brain.

Drs.

Buck and Axel tackled a two-part question about smell:

- How do

mammals detect so many different chemicals as having smell?

- How does

the brain translate information (about smell) into perceptions?

|

Buck chose a novel approach to solve the mystery of how the nose-brain

system recognizes the thousands of odor molecules (called "odorants")

floating around us in the world. The question was: Did many very specific

receptors detect the odorants, or only a few receptors, working overtime?

The approach was: Search for the genes encoding receptors found only in

the nose, instead of searching for the receptors themselves. Buck's former

mentor, Axel, called this approach "an extremely clever twist."

The research to solve this receptor mystery borrowed clues from other

studies on receptors.

Clue one: Many receptor

proteins have a similar structure: they

cross the cell membrane seven times, creating a zig-zag shape that

resembles a snake.

Clue two: These proteins often

interact with

another type of protein, G-proteins, to transmit signals to the inside of

the cell.

Clue three: These proteins

often share stretches of DNA in common.

These clues helped Buck to design probes (think of a fishing hook shaped

for a certain fish) to identify these sequences in rodent DNA. The better

you

know what you are fishing for, the better you can design the "hook" to

catch it.

By carefully designing the "hook," or probe, Buck saved years of work.

Once genes had been identified in rodent DNA, a similar approach was used

to fish out the genes in collections of DNA from other species such as

humans, mice, dogs, catfish and salamander.

Buck is expanding her research on odorant receptors to other types

of receptors, such as those involved in bitter tastes, sweet tastes and

pheromones. Pheromones

are chemicals produced by animals to signal to others in their species.

The first pheromone, identified in the 1950s, was an attractant signal for

silkworm moth mating. Research on insects, though, is much easier than on

humans, and the topic of human pheromones is controversial. Don't invest

in that pheromone-enhanced perfume yet. The jury is still out on whether

you can improve your attractiveness by exuding certain chemical signals.

Animals have a vomeronasal organ (VNO) that responds to pheromones, but no

such organ has been pinpointed in humans. Axel has noted that if humans

have one, it's most likely disrupted by plastic surgery in those who have

nose jobs.

Buck is expanding her research on odorant receptors to other types

of receptors, such as those involved in bitter tastes, sweet tastes and

pheromones. Pheromones

are chemicals produced by animals to signal to others in their species.

The first pheromone, identified in the 1950s, was an attractant signal for

silkworm moth mating. Research on insects, though, is much easier than on

humans, and the topic of human pheromones is controversial. Don't invest

in that pheromone-enhanced perfume yet. The jury is still out on whether

you can improve your attractiveness by exuding certain chemical signals.

Animals have a vomeronasal organ (VNO) that responds to pheromones, but no

such organ has been pinpointed in humans. Axel has noted that if humans

have one, it's most likely disrupted by plastic surgery in those who have

nose jobs.

Image courtesy of the Nobel

Foundation

| A former student's (Ewen Callaway) recollection on

Linda Buck's

approach to scientific questions: "In my discussion with

her, I was struck by her openness to different solutions to basic problems

in neurobiology. She was willing to embrace a theory different from her

own as long as it was based on careful research and good science. She was

also extremely creative. I had read the literature pretty thoroughly

before I met with her, and still she opened my eyes to a number of ideas

about the molecular biology of smell that had not been explored by other

scientists."

Officials at Columbia University, where Axel has spent his entire research

career, responded to the news of the Nobel Prize with praise for Axel:

"...his research solves the puzzle of how we translate sensations

around

us into knowledge that is key for our survival..."

--Columbia University President Lee Bollinger

"(Their) experiments represent the highest form of creativity,

scientific

discipline and scholarship."

--David Hirsch, executive vice president for research

|

Did You Know?

|

- Perfume makers claim that they can identify as many as 5,000

different

types of odorants. (Kandel, et al., Principles of Neural Science, 4th Ed.,

page 625).

- Mice have approximately 1,000 odorant receptors encoded by an

estimated 1,500 genes. Humans have around 350 odorant receptors. ( "Mechanisms

Underlying Perception and Aging" from the HHMI)

- Bloodhounds have approximately 4 billion olfactory receptor cells;

humans have approximately 12 million of these cells. (Shier, D., Butler,

J. and Lewis, R. Hole's Human Anatomy & Physiology, Boston: McGraw Hill,

2004.)

- Dr. Linda Buck is the 11th woman to receive a Nobel Prize in sciences

in the 103 years the prizes have been awarded.

|

|

projections, called cilia, that contact the mucus. The cilia contain the

odorant receptors. The other part of the neuron sends a single axon through the bony plate above the nasal cavity to the

olfactory bulb.

projections, called cilia, that contact the mucus. The cilia contain the

odorant receptors. The other part of the neuron sends a single axon through the bony plate above the nasal cavity to the

olfactory bulb.

![[email]](./gif/menue.gif)