Chapter 9: DIAGRAM OF THE

| Contents | |

|---|---|

| The Admonition for Mindfulness Studio | 178 |

| Comments of Chu Hsi and Others | 179 |

| T'oegye's Comments | 180 | Commentary |

| The Centrality of Mind and Its Cultivation | 181 |

| Mindfulness through Propriety: Beginning from the External | 182 |

| Mindfulness as Recollection and Self?Possession | 185 |

| Mindfulness as Reverence | 187 |

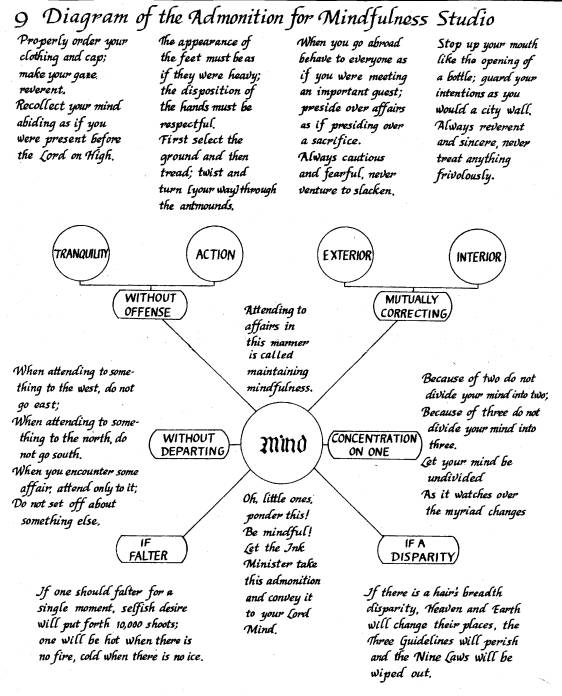

Mindfulness stands at the heart of Chu Hsi's teaching as it is understood by T'oegye, and in this chapter T'oegye presents the text which served as his own source of inspiration, constant reflection, and self-examination. Describing his early formation, he says: "The Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate in the Hsing-li ta-ch'üan gave me a start [in learning]; the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio was the matter for my practice."1 In later years the Admonition was pasted to the wall of his study as a constant reminder; in this he was following the example of Chu Hsi, who composed the Admonition and put it on the wall of his study.

As the comments in this chapter indicate, the Admonition approaches mindfulness topically, presenting its various applications to activity and quiet, to external deportment and internal attitudes. In addition to the text in the last chüan of the Hsing-li ta-ch'üan where T'oegye first encountered it, the Admonition appears in the ChuTzu ch'üan-shu, 85, and in the final chiian of the Classic of the Mind-and-Heart. The text as presented here follows a variant reading found in the Classic,2 and most of the comments T'oegye appends to it likewise appear there. Thus this chapter, as well as the one which precedes it, directly reflects the continual influence of Chen Te-hsiu's Classic on T'oegye's thought.

178 Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio

The Admonition for Mindfulness Studio

Properly order your clothing and cap and make your gaze reverent; recollect your mind and make it abide, as if you were present before the Lord on High.4 The appearance of the feet must be as if they were heavy, the disposition of the hands respectful. First select the ground and then tread; twist and turn [your way] through the antmounds.5

When you go abroad, behave to everyone as if you were meeting an important guest; preside over affairs as if presiding at a sacrifice.6 Always cautious and fearful,7 never venture to slacken. Stop up your mouth like the opening of a bottle, and guard your intentions as you would a city wall. Always reverent and sincere,8 never venture to treat anything frivolously.

When attending to something to the west, do not go east; when attending to something to the north, do not go south. When you encounter some affair attend only to it; do not set off about something else. Because of two [matters to be dealt with] do not divide your mind into two; because of three do not divide your mind into three. Let your mind be undivided9 as it watches over the myriad changes. Attending to affairs in this manner is called maintaining mindfulness. Both action and tranquility should be without offense; one's exterior and interior should mutually rectify one another.

If one should falter for a single moment, selfish desire will put forth ten thousand shoots;10 one will be hot when there is no fire, cold when there is no ice.11 If there is a hair's breadth disparity [from what is right] Heaven and Earth will change their places;12 the Three Guidelines will perish and the Nine Laws will be wiped out.13

Ah, little ones, ponder this! Be mindful! Let the Ink Minister take this admonition and convey it to your Lord Mind!

Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio 179

Comments of Chu Hsi and Others

Chu Hsi says: "If a circle is to be proper, its curve must be round and in accord with the norm provided by the compass; if a square is to be proper, its angles must be square and in accord with the norm provided by a square. `Antmounds' refers to the mounds made by ants; there is an old saying which speaks of mounting a horse and twisting and turning [one's way] through the antmounds. This refers to the fact that the path lying between the antmounds is tortuous and narrow; thus it is a difficult feat to mount one's horse and twist and turn, threading a path through them without breaking one's gait."14

"Stopping up one's mouth like the opening of a bottle means not saying anything recklessly. Guarding one's intention as one would the wall of a city means preventing any depravity from entering."15

And again he says: "One who would be mindful must focus his attention on one thing. If at first there is one matter and another is added, then [one's mind becomes divided] into two, for that makes two matters. If originally there is one matter and two are added, then [the mind becomes divided] into three, for that makes three matters.16 Faltering for a single moment refers to the temporal aspect; `a hair's breadth disparity' is said in terms of the matter itself."17

Wu Lin-ch'uan18 says: "The Admonition consists of ten sections of four lines each. The first section says that in tranquility one should be without offense, and the second that in action one should be without offense. The third speaks of the correctness of one's external [deportment], and the fourth of the correctness of one's interior [dispositions]. The fifth speaks of how, when the mind is proper, it will fully reach to the matter in hand [without being sidetracked], while the sixth speaks of concentrating on one thing [at a time] in dealing with affairs.

180 Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio

The seventh sentence is a general conclusion to the first six. The eighth describes the ills which attend upon not succeeding in being `without departing' and the ninth describes the ills that follow from not being able to `concentrate on one [thing].' The tenth sentence is a general conclusion to the entire work."19

Chen Te-hsiu20 says: "There is nothing more that could be said about the meaning of mindfulness. Those whose wills are firmly set upon pursuing sage learning ought to become thoroughly versed in this and go over it repeatedly."21

T'oegye's Remarks

Master Chu, in his own prefatory remarks to the above Admonition says: "After reading the Admonition on Concentrating on One Thing, by Chang Ching-fu [Shih],22 I took its general purport and made this Admonition for Mindfulness Studio and put it on the wall of my study as a reminder for myself."23 And again: "This is a topical treatment of mindfulness, so the exposition is made from a number of standpoints."24

I would suggest that this exposition of the topics offers a good foundation for the actual practice [of mindfulness]. Wang Lu-chai (Po)25 of Chin-hua arranged the topics to make a diagram and achieved this kind of clear and well-ordered presentation in which everything finds its proper place. One should personally experience and get a taste of its meaning, cautioning oneself and using it for self-reflection in the course of daily life and in whatever comes to mind. If one assimilates it in this way, he will never doubt but that "mindfulness constitutes the beginning and the end of sage learning."26

Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio 181

Commentary

The Centrality of Mind and Its Cultivation

The centrality of the mind-and-heart in self-cultivation is graphically evident in this diagram. T'oegye discusses the importance of the mind and the essentials of its cultivation as follows:

The mind is the foundation of all affairs and the nature is the origin of all good; therefore when the former Confucians discussed learning they unfailingly regarded "recovering the errant mind"27 and "nurturing the virtuous nature"28 as the very first thing to which one must apply oneself as the means whereby one fulfills his fundamental constitution. This they regarded as the foundation for fulfilling the Tao and developing the full extent of one's virtue; as for the essence of the way to apply one's effort, what need is there to seek it in anything else!

Likewise it is said: "Concentrate on one thing without departing [from it],"29 "Be cautious, be apprehensive."30 The application of concentrating on one thing runs throughout both the active and quiet states, while the field of caution and apprehension is entirely in the not-yet-aroused state. Neither of these can be omitted. And regulating the exterior in order to nurture the interior is an even more urgent matter. Therefore instructions such as the "Three Self-examinations,"31 the "Three Things Valued,"32 and the "Four Things Not Done"33 all concern responding [to affairs] and dealing [with others]; this likewise is what is meant by nurturing one's fundamental constitution. If one does not approach it in this fashion and one-sidedly emphasizes applying himself to just the mind, it is rare not to fall into Buddhist views. (A, 16.6b-7a, pp. 404-405, Letter to Ki Myŏngŏn)

In this passage three aspects of the cultivation of the mind-and-heart emerge: (1) maintaining a concentrated, self-possessed state of mind ("concentrate on one thing without departing"); (2) a reverential dimension ("be cautious, be apprehensive"); (3) beginning by regulating the external in order to cultivate the internal. These aspects also are evident in Chu Hsi'sAdmonition for Mindfulness Studio. We shall discuss each in turn, beginning with the third.

182 Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio

Mindfulness through Propriety: Beginning from the

External

Traditional Confucianism had simply taken the whole person as the object of self-cultivation. It approached this through a relatively common-sense, externalistic methodology which stressed forming a good character through self-discipline and the inculcation of good habits, with the disciplined observance of the rules of propriety serving as a major means to this end. When Buddhism entered East Asia, it brought with it a new focus on the inner life of the mind, and its sophisticated meditative techniques for the transformation of consciousness made Confucian methodology look embarrassingly simple and superficial by contrast. When the Neo-Confucian movement finally revitalized the Confucian tradition after centuries of Buddhist predominance, it is not surprising that it was characterized by a new awareness of man's interiority, now taking the mind-and-heart as the central object of self-cultivation and elaborating the doctrine of mindfulness as the appropriate and essential methodology. The Neo-Confucians had learned much from the Buddhists.

Maxims of the traditional propriety, such as the "Four Things Not Done," however, continued to have a serious place in self-cultivation. Chu Hsi's Admonition begins, one notes, not with the inner life of consciousness but with dress, demeanor, physical comportment, and one's attitude in dealing with others. But this external self-discipline is now given an explicitly internal orientation: "Regulate the external in order to nurture the interior," as T'oegye puts it. Many passages emphasize this as the most concrete and practical approach to regulating the mind-and-heart. T'oegye says:

I have heard that the ancients, wishing to preserve the mind-and-heart that is without form or shadow, would unfailingly apply themselves to that which has form and shadow that could be relied upon and maintained. This is what the "Four Things Not Done" and the "Three Things Valued" of Yen Hui and Tseng Tzu are. Therefore in his letter replying to He Shu-ching Master Chu says: "From the level of Yen Hui or Tseng Tzu34 on down, it is necessary to apply one's practice to matters such as one's seeing and listening, one's

Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio 183

speech and demeanor one's way of expressing oneself. For man's mind has no form and its coming and going is not fixed; one must preserve and settle it in accord with an established norm, then of themselves both the inner and outer will become steady. This is the absolute essence of day-to-day practice. If you examine it in this light, you will realize that the inner and outer have never been separated, and what is described as being serious, properly ordered, controlled, and grave, is truly the means by which one preserves one's mind-and-heart. "35 . . . One may not split the inner and the outer into two separate matters and regard the outer as coarse, shallow, and easy to do, while regarding the inner as subtle and mysterious and a practice difficult to attain. (A, 29,12a-b, p. 682, Letter to Kim Ijŏng)

While the above passage emphasizes the practicality of this kind of approach, it is also clear that the practicality is conjoined with a value orientation expressed in terms of avoiding a Buddhistic devaluation of the external in attending to the internal. Confucian self-cultivation has as its final goal not some kind of personal, inner enlightenment, but the proper conduct of human relationships and government. Neo-Confucians enlarged that tradition by introducing a more personal, inner dimension to self-cultivation that held the promise of a kind of personal fulfillment or awakening: one could become a sage. But Confucian sagehood could never be divorced from the external perfection of man as a social being, and true to this tradition the Ch'eng-Chu school makes every effort to hold the internal and external together as two aspects of a single unity. Proper deportment in dress, speech, and conduct are not only useful stratagems for controlling the mind, but important values in themselves. Thus underlying the stress on this approach is an ultimate Confucian concern for the external world of human society and the proper conduct of human relationships. This is the distinctively Confucian dimension of the cultivation of the mind-and-heart. As T'oegye said above (see previous sec.): "If one does not approach it in this fashion and one-sidedly emphasizes applying himself to just the mind, it is rare not to fall into Buddhist views."

As the theory of mindfulness developed, a number of different descriptions of it emerged; some of these were more externalistic, others more directly descriptive of a state or condition of the mind. If mindfulness entailed some kind of altered state of consciousness,

184 Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio

one might see a progression from external to internal practice in these descriptions, but such is not the case. Thus T'oegye sees the externalistic approach as not only most concrete and practical, but as encompassing what is signified by more internally oriented descriptions:

Now, in seeking where to begin applying your effort, you should take Master Ch'eng's "properly ordered and controlled, grave and quiet"36 saying as the first matter. If you practice it for a long time and are not neglectful, you will personally experience that you have -not been deceived by his saying that "then the mind will become single and will not offend by wrong or depraved thoughts."3' If your exterior is grave and quiet and your mind within is single, then what is referred to as "Focus on one thing; do not depart,"" what is described as "The mind is recollected and does not allow a single thing [to have hold on it]"39 and what is called "always being bright and alert"40 will all be included in it without having to depend on a separate particular form of practice for each item. (A, 29.13a-b, p. 683, Letter to Kim Ijŏng)

A final matter of importance for T'oegye in making the externalistic approach primary has to do with the delicate balance between neglecting to make enough effort and going too far, artificially forcing oneself or "helping [the corn] grow" by pulling on it, as described by Mencius.41 Especially with regards to a mind-oriented cultivation, forcing could be disastrous, but some effort is obviously necessary. T'oegye himself ruined his health as a young man by excesses in this regard and never fully recovered it. T'oegye feels that the external approach, which admits of simple and concrete norms, offers an important advantage in this respect:

[Yi Tokhong]42 said: The explanations of mindfulness are multiple; how can I avoid being ensnared in the problem of being either negligent or artificially helping [it grow]?

[T'oegye] said: Although there are many explanations, none are more to the point than those of Ch'eng [I], Hsieh [Liang-tso], Yin [T'un], and Chu [Hsi]. But among those who pursue learning, some wish to apply themselves to practicing "always being bright and alert," others to "not allowing a single thing [to have hold on their minds]";43 thus they set their minds in advance on seeking [a particular condition] or they go about trying to manage [the

Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio 185

mind] a particular way. It is very rare that this does not give rise to the problem of "pulling up the shoots [to help them grow]"44 But if one, not wishing to "help it grow," does not use even a little deliberateness, it is likewise rare that this does not end up with the situation of neglecting the work and not doing the weeding.

For beginning students nothing is better than devoting one's practice to being "properly ordered and controlled, grave and quiet."45 In this there is no place for searching after [a particular mental condition] or trying to manage [the mind] in a particular way; it is just a matter of establishing oneself in accord with the fixed norm (lit. "square, compass, and ink-line"), being "cautious and watchful in the hidden, secluded places [where you are not observed],"46 and not allowing the mind-and-heart to get away the least bit." Then, after practicing this for a long time, one naturally becomes "always bright and alert," one naturally does "not allow a single thing [to have hold on the mind]"-and this without the least problem regarding being negligent or helping [it grow]. (ŎHN, 1.14b-15a, B, pp. 795-796)

In conclusion, we might note that while T'oegye thus emphasizes the externalistic approach to mindfulness, he by no means excludes a more internalistic, even meditative, approach. The passages we have seen have dealt mainly with how to begin to approach mindfulness. For beginners the external approach is relatively easier and safer, and insures a proper value orientation. But for the more advanced, the cultivation of a deep inward quiet through meditation also has its place. This will be taken up in the discussion of the next chapter.

Mindfulness as Recollection and Self-Possession

While attending to external propriety may be the most effective or secure method of approaching mindfulness, the essence of mindfulness is rather a matter of a constantly maintained state of mental recollection and self-possession, a state in which one may quietly focus on the matter at hand. This is what such definitions as "always bright and alert," "the mind is recollected and not a single thing is allowed [to have a hold on it]," or "Concentrate on one thing;

186 Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio

do not depart,"48 are trying to formulate. The last of these, which appears at the center of our diagram, became a favorite description of mindfulness in the Ch'eng-Chu school; although it is a description of a mental state, at the same time it is more like the externalistic approach discussed above in being specific and concrete and immediately practicable.

The ability to concentrate upon the matter at hand is an obvious condition for both the investigation of principle and responsiveness to principle embodied in the affairs with which one must deal. But T'oegye explains that this single-minded focus cannot become an end in itself:

[In your letter] you say that when you are thinking of one thing and something else presents itself, you try to avoid relaxing [your attention] to consider it. This likewise is a matter of the mind's not having two [simultaneous] functions and is fitting with respect to applying oneself to "concentrating on one thing." Nevertheless, if one explains it one-sidedly like this, I fear it will also prove to have aspects which obstruct principle .... If the mind meets a certain matter to which it ought to respond and does not respond, then it is being obstinately insensitive and fails to exercise its proper office. If one deals in this way with the ten thousand changes, how will one be able to attain due measure and degree! . . . If when one meets a number of affairs which come up together he attends at one moment to the left, at the next to the right, once to that, once to this, how could they be properly considered when all mixed up like that. They are to be considered in turn and dealt with in turn; it is just a matter of the mind's self-mastery being present and preeminent as the governing principle (kung) of the multitude of affairs. Then the subtle wellsprings of the affair at hand will finally appear, the four limbs will be silently instructed, and none of the intricacies of the matter will be missed. (A, 28.17b-18a, p. 660, Letter to Kim Tonsŏ)

Mindfulness as the ability to quietly focus the mind is different from simply becoming engrossed or absorbed in a situation, a case in which the object possesses the mind and becomes an obstacle to dealing appropriately with the flow of changing events. The mind must focus on a situation in order to think it through and handle it correctly, but the power of concentration must be rooted not in the attraction of the object, but in the mind's self-possession, which frees

Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio 187

it from the hold of any object and hence from the power of any object to inappropriately distract it. T'oegye praises a description of "concentrating on one thing" sent him by Yi I (Yulgok) for bringing out these nuances:

Your discussion of the meaning of "concentrating on one thing without departing" and "dealing responsively with the ten thousand changes" is very good. Your quoting Master Chu's "Following the matter [at hand] one responds as appropriate; the mind fundamentally is not predisposed to have any particular thing [as its object]," and Mister Fang's "The midst [of the mind] is empty, but there is a master there," makes it even more precise.49 (A, 14,24b, p. 372, Letter to Yi Sukhŏn)

Ultimately it is this empty self-mastery of the mind which makes possible the quiet concentration on the matter at hand. "Empty" in this context means not only the absence of any particular object, but more fundamentally, the absence of factors which predispose one to particular objects, that is, the absence of self-centered desires for personal gain, reputation, and the like which give things a hold over the mind. In this respect, mindfulness goes beyond mere mental selfdiscipline, for the perfection of this kind of self-mastery demands a high level of moral cultivation.

Mindfulness as Reverence

Chu Hsi's Admonition for Mindfulness Studio says, "Recollect your mind and make it abide, as if you were present before the Lord on High . . . When you go abroad, behave to everyone as if you were meeting an important guest; preside over affairs as if presiding at a sacrifice." The term kyŏng (ching), which we have been translating as "mindfulness," more traditionally meant rather "reverence." While the translation of kyŏng/ching as "mindfulness" brings out the technical Neo-Confucian understanding of it as a method of constant mental self-possession and single-mindedness, these passages in the Admonition

188 Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio

are a reminder that the traditional sense of the term also remains. In fact, not only does reverence remain as an aspect of mindfulness; one might well say that it is the inner soul or animating force which inspires the methodological practice of mindfulness. If "mindfulness" bespeaks the method, "reverence" bespeaks the fundamental attitude, the motivation which is the deeper meaning of the method.

Neo-Confucians easily alternated the language of principle and ancient concepts of divine governance to emphasize the ultimate seriousness of cultivating the mind-and-heart and attending with mindful reverence to daily affairs. T'oegye exhorts King Sŏnjo:

Thus the Book of Odes speaks of reverence for the Tao of Heaven, saying: "Reverence it, reverence it! Heaven is lustrous, its Mandate is not easy! Do not say it is lofty and high above; ascending and descending, it watches daily over your affairs."50 For with regard to the issuing forth of the principle of Heaven, there is nothing in which it is not present and no time that it is not so. If in one's daily conduct there is a slight deviance from the principle of Heaven and one slips into following [selfish] human desire, this is not how one reverences Heaven .... The oversight of Heaven is bright and perceptive; how can it but be feared! Therefore the Odes again says: "Fear the majesty of Heaven; at all times maintain [your awe]. "51 . . . This is the nature of the principle of reverencing and fearing Heaven. Likewise Mencius says: "Preserving one's mind and nurturing one's nature is the way to serve Heaven." 52 The Tao of serving Heaven is just a matter of preserving and nurturing the mind and the nature and that is all. (ŎHN, 3.23a-b, B, p. 830)

The ancient Book of Odes frequently referred to a personal, transcendent Being who watches over and governs the affairs of men. By the time of Confucius, however, this belief was already evolving into less personalistic concepts such as Heaven or the Tao. The object of religious reverence and awe was not abandoned and lost in this process, but rather rendered immanent as a governing or directive agency within the universe itself. The Neo-Confucian formulation of the philosophy of principle or the Supreme Ultimate was the heir of this process. Principle is immanent within the things of the world, the affairs of human society, and in man's own nature, but it does not thereby become mundane; rather it indicates that within

Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio 189

the mundane which itself demands our ultimate seriousness and reverence.

The ordinariness of daily life, however, easily dulls the awareness of the ultimacy incorporated therein. As a corrective, Neo-Confucians at times self-consciously used the archaic, more overtly religious language of the Book of Odes to renew the proper sense of that in which they were engaged. One of T'oegye's favorite passages in the Classic of the Mind-and-Heart illustrates this clearly:

The Book of Odes says: "The Lord on High watches over you; do not be of two minds." And again it says: "Do not be of two minds, do not be negligent; the Lord on High watches over you."53

This is followed with the comment:

In my humble opinion, what is meant by this ode is such that, although its immediate reference is to attacking [the evil king] Chou, nevertheless when one who pursues learning (chants these verses), in the course of daily life there is a shivering feeling, as if the Lord on High were actually watching over him; then how can this but be of great help in his keeping out depravity and fostering sincerity. Or again, there are those who see what is right but are not necessarily courageous in doing it, or because of considerations of benefit and harm, gain and loss, divide their minds. These likewise should learn to taste these words in order to become more determined.54

These remarks distil the essence of the sense of reverence and seriousness, the "fear of the Lord" which is the inner spirit of mindfulness. The "as if" is no hindrance: the "shivering feeling" of reverent awe is as appropriate to a life lived in the immanent presence of the Supreme Ultimate or principle as it is to being in the presence of the Lord on High. Thus for a man like T'oegye this passage hits just the right note: "I have a deep love for its words; every time I recite and savor them I am moved more than I can say."55

NOTES

9. Diagram of the Admonition for Mindfulness Studio

1. ŎHN, 1.206, TGCS, B, p. 798.

2. See below, note 9.

3. Reference to I-shu, 18.3a.

4. Reference to I-shu, 11.2a, a paraphrase of Odes, #266.

5. According to Chu Hsi's explanation, YL, 105.8a, these are not the familiar small anthills, but hillocks or towers of mud which are found in north China; they are close together, the path between them being like narrow, twisting alleys.

6. Analects, 12:2.

7. Odes, #195, also quoted in Analects, 8:3, and Classic of Filial Piety, ch. 3: "Always cautious and fearful, as if overlooking a deep gulf, as if treading on thin ice. "

8. Book of Rites, ch. 24, On What is Proper in Ancestor Sacrifices (Li chi cheng-i, chuan 47, in Shih-san thing chu-shu, p. 1593): "How reverent! How sincere! As if [fearing] not to succeed, as if about to lose it; their filial and reverent dispositions are indeed perfect!"

9. The versions of the Admonition found in Chu Tzu ta-ch'uan, 85.6a, and Hsing-Li ta-ch'üan, 70.24a have ching ("discerning, refined") instead of hsin ("heart, mind") in this phrase, a reading which would make it a quote of the Book of Documents, pt. 2, 2.15; "The human mind is insecure, the mind of the Tao is subtle; be discerning, be undivided. Hold fast the Mean!" The text as it appears in the annotated and supplemented version of the Classic of the Mind-and-Heart (Hsin-ching fu-chu, 4.21a) has the reading followed by T'oegye.

10. A paraphrase of I-shu, 15.9a.

11. Paraphrasing Chuang Tzu, ch. 11, which says of man's mind-and-heart: "Its heat is that of burning fire, its cold that of solid ice," a reference to the feelings of anger and fear, respectively.

12. Ssu-ma Ch'ien's preface to the Shih chi (Shih chi, chüan 130): "Miss it by a hair's breadth and it becomes a discrepancy of a thousand li. " He ascribes the saying to the Book of Changes, but it is no longer to be found there. The saying became a commonplace of which Neo-Confucians were particularly fond. It applies both to dealing with affairs, and even more to the world of the intellect, where it was felt slight inaccuracies might ramify into a serious departure from the true Tao--especially slipping into Buddhism.

13. The "Three Guidelines" are the bonds between ruler and minister, father and son, and husband and wife, the former providing the standard for the latter in each of these relationships. The "Nine Laws" refers to the nine sections of the Grand Plan (Legge, Book of Documents, V.4), which constitute a virtual charter for civilization.

14. YL, 105.8a, abbreviated.

15. YL, 105.8a.

16. YL, 105.82.

17. Quoted in Hsin-ching fu-chu, 4.216.

18. Lin-ch'uan was the honorific name of Wu Ch'eng (1249-1333); his courtesy name was Yu-ch'ing, and he is also known by another honorific name, Tsao-lu. He was a leading Yüan dynasty exponent of the Ch'eng-Chu school of thought. An account of him appears in the Ihak T'ongnok, 10.8a-1 lb, TGCS, B, pp. 507-509.

19. Quoted in Hsin-ching fu-chu, 4.226.

20. On Chen, see Introduction, note 23.

21. Hsin-ching fu-chu, 4.226.

22. On Chang Shih, see chapter 7, note 29.

23. Chu-tzu ta-ch'üan, 85.56.

24. YL, 105.76.

25. The courtesy name of Wang Po (1197-1274) was Hui-chih, and Luchai was his honorific name. He was a leading scholar who studied with He Chi, a disciple of Chu Hsi's son-in-law and chief doctrinal heir, Huang Kan. The doctrine of mindfulness was one of his chief concerns, and this diagram arose through his own attempt to make Chu Hsi's Admonition the norm and guide of his daily life. For an account of him, see Sung-Yüan hsüeh-an, chüan 75.

26. Paraphrase of YL, 12.76.

27. Mencius 6A:11.

28. Ibid., 7A:1.

29. I-shu, 15.1 a.

30. Doctrine of the Mean, ch. 1.

31. Analects, 1:4: "Tseng Tzu said: `Everyday I examine myself on three points: In acting on behalf of others, have I been loyal; in my intercourse with friends, have I been faithful to my word; regarding [the instruction] that has been passed on to me, have I versed myself in it."

32. Analects, 8:4: "With regard to the Tao, the gentleman especially values three things: that in his deportment and manner he keep far from violence and heedlessness; that in regulating his countenance he keep near to good faith; that in his words and tones he keep far from lowness and impropriety."

33. Analects, 12:1: "Yen Yüan said: "I beg to ask the items [involved in overcoming oneself and returning to propriety].' The Master said: "Do not look at what is contrary to propriety, do not listen to what is contrary to propriety, do not say what is contrary to propriety, make no movement which is contrary to propriety' "

34. Confucius' two foremost disciples.

35. This is a slightly abridged quote from a letter of Chu Hsi to He Shu-ching which T'oegye cites in his account of He Shu-ching (Ihak T'ongnok, 3.7a, TGCS, B, p. 311). However the passage does not appear in any of Chu Hsi's 32 letters to He which appear in Chu Tzu ta-ch'üan, chüan 40, nor is it included in T'oegye's abridged edition of Chu Hsi's letters, the Chusŏ chŏryŏ.

36. I-shu, 15.66.

37. I-shu, 15.66.

38. I-shu, 15.1 a.

39. A saying of Ch'eng I's disciple, Yin T'un. On Yin, see above, chapter 4, number 8.

40. This is Hsieh Liang-tso's expression of what constitutes mindfulness. See HLTC, 46.146. On Hsieh, see above, chapter 7, number 41.

41. Mencius 2A:2.

42. On Yi Tŏkhong, see above, chapter 3, nunber 22.

43. On these sayings, see above, numbers 40 and 39 respectively.

44. Mencius, 2A:2.

45. Ch'eng I's description, I-shu, 15.66.

46. Paraphrase of Doctrine of the Mean, ch. 1.

47. Reference to Mencius, 6A:11.

48. See above, notes 40, 39, 38 respectively.

49. The original letter from Yi I appears in Yulgok chŏnsŏ (The Complete Works of Yi I), 9.26-3a. I have not been able to locate the original source of either of these quotations. According to the annotation in T'oegye munjip koch'ung, 4.306 (TGCS, B, p. 1141) the "Mister Fang" referred to is Fang Feng-ch'en (fl. c. 1250), a Sung dynasty scholar. His courtesy name was Chün-hsi, and his honorific name was Chiao-feng.

50. Odes, #288.

51. Odes, #272.

52. Mencius, 7A:1.

53. Hsin-ching fu-chu, 1.46; the passages quote Odes #236 and #300 respectively.

54. Hsin-ching fu-chu, 1.Sa. T'oegye (Reply to Cho Sagyŏng, A, 23.31b-32a, p. 563) notes that there is some doubt about the ascription of this passage to Chu Hsi, since it cannot be found in his commentary on the Odes, but he nonetheless feels it is possible the passage comes from somewhere else in Chu's works and is not inclined to ascribe it to the pen of Chen Te-hsiu.

55. Reply to Kim Tonsŏ, A, 28.22b, p. 662.