Coordinated Searching and Target Identification Using Teams of Autonomous Agents

Many modern autonomous systems actually require significant human involvement. Often, the

amount of human support and infrastructure required for these autonomous systems exceeds

that of their manned counterparts. This work involves increasing both the tactical and

strategic decision making capabilities of various autonomous systems. The application

considered is the problem of searching for targets using a team of heterogeneous agents.

The system maintains a grid-based world model which contains information about the probability

of a target being located in any given cell of the map. Agents formulate control decisions

for a fixed number of time steps using a modular algorithm that allows for capabilities and

characteristics of individual agents to be encoded in several parameters. The resulting

search patterns executed by the agents guarantee an exhaustive search of the map in the

sense that all cells will be searched sufficiently to ensure that the probability of a

target being located in any given cell is driven to zero. This system was simulated

using high fidelity simulations with heterogeneous agents in complex and dynamic environments.

After performing successfully in simulation, these algorithms were then verified and validated

on a distributed human-in-the-loop simulator. This system allows a human operator to handle

low level tasks such as state stabilization and signal tracking while preserving the contributions

of the autonomous algorithm. Finally, flight test results are presented showing the benefits of

augmenting a human system with these types of autonomous algorithms.

Autonomous Target Identification

A primary goal in a searching mission is typically to find a target in some region. As an agent performs its search, it may encounter the target it

is searching for or it may encounter an object which produces a sensor reading but is not the desired target (a false anomaly). The main challenge

in this situation is to correctly identify or classify these encountered anomalies. Typically, the target identification process is handled by a

human operator. It is the operator's responsibility to monitor sensor outputs and determine if readings correspond to the desired target, false

anomalies, or extraneous noise. Many unmanned systems carry optical sensors such as cameras or infra-red imaging devices. Autonomously processing

the output of these sensors and classifying readings requires significant computational resources and effort and in many cases, a human operator will

outperform a computer generated algorithm in terms of classification accuracy and reliability. This can be mainly attributed to the fact that the

output of the sensor is a complex multi-dimensional set of data with many features being explicit and more easily extracted and recognized by a

trained human operator. As the number of agents involved in the search mission increases, so does the required number of human operators. A large team

of expensive agents with sophisticated sensors may not be the most effective system.

A more scalable and implementable team would be comprised of several smaller agents with less complex sensors. These more primitive sensors may output

a smaller dimension signal which a human operator may have difficulty interpreting. Automating the target identification process may have more promise

in this context. In a noisy environment, it becomes difficult for a human operator to classify sensor readings and assign confidence in these readings

because the useful features are hidden in the signal. In this situation, the useful features in the signal can be extracted and then used to train a

machine learning algorithm to perform the classification which may have better accuracy and reliability than the human operator.

This work contributes to the large area of research in autonomous target identification. The main research focus is to develop a system which processes

the output from a low dimensional sensor and extracts relevant features from which to train a classifier. Some topics covered in this chapter include

sensor models of environments and targets, machine learning algorithms for autonomous target identification, and investigation of the use of particle

filters instead of the traditional HMMs to incorporate temporal smoothness and regularity into the target identification system.

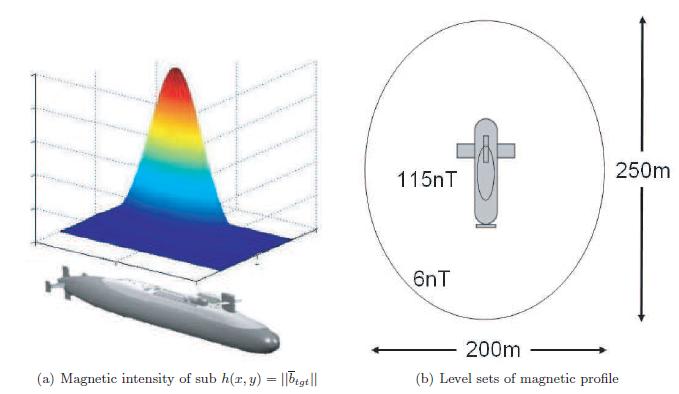

The example used in this work involves an agent searching for a target based on its magnetic signature. The agent is equipped with a simple scalar

magnetometer which can measure the magnetic field magnitude at its current location. The unique contribution of this research is a highly accurate target

identification system which uses low dimensional sensor returns to classify anomalies.

Figure 1: Proposed magnetic signature of submarine

Occupancy Based Maps

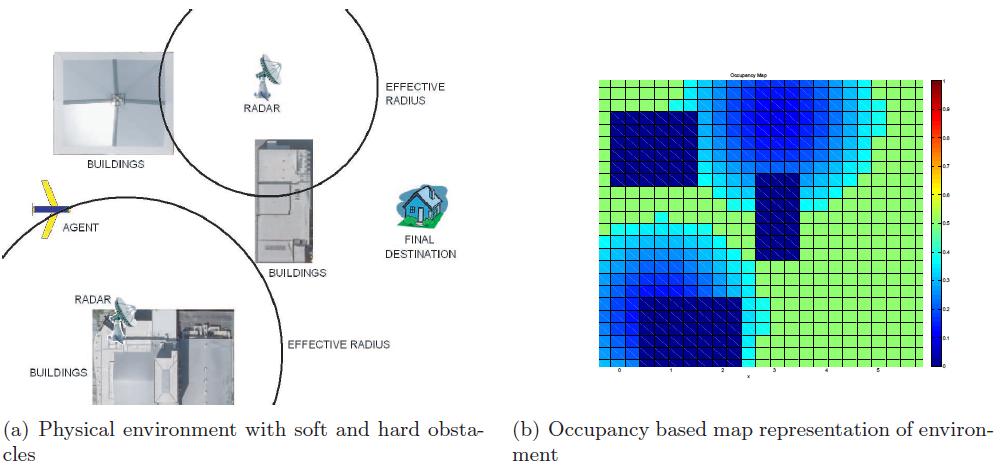

In order to effectively search a two dimensional domain for a target, the system must keep track of the state of the world in terms of possible target locations.

To do this, an occupancy based map is employed. Recall that these constructs were originally formalized by Elfs

but we add functionality such as Bayesian score updates and time varying models to the maps to accommodate our algorithm.

The search domain is discretized into rectangular cells. Each cell is assigned a score which is the probability that the target is located in that cell. This is similar

to a two dimensional, discretized probability density function. The spatial domain of the occupancy based map consists of a

box where x is between some interval and similarly for the y dimension.

Figure 2: Abstraction of environment into an occupancy based map

Multi-Agent Searching

With the occupancy map framework in place, the strategic searching strategy can be addressed in this chapter. The problem of searching an area using a team of

possibly heterogeneous, autonomous agents is still an open problem. Many of the sources in the current literature provide methods

to perform this mission with varying degrees of success. For example, randomized coverage methods are unable to provide guarantees regarding map coverage and

target detection. Other approaches such as Bayesian searching have difficulties embedding information about a complex environment into the algorithm. In terms

of sub-tasks such as path planning, methods such as evolutionary computation may prove to be prohibitively expensive in terms of computational resources.

This section focuses on addressing these issues and developing a modular and scalar algorithm that can be applied to this situation.

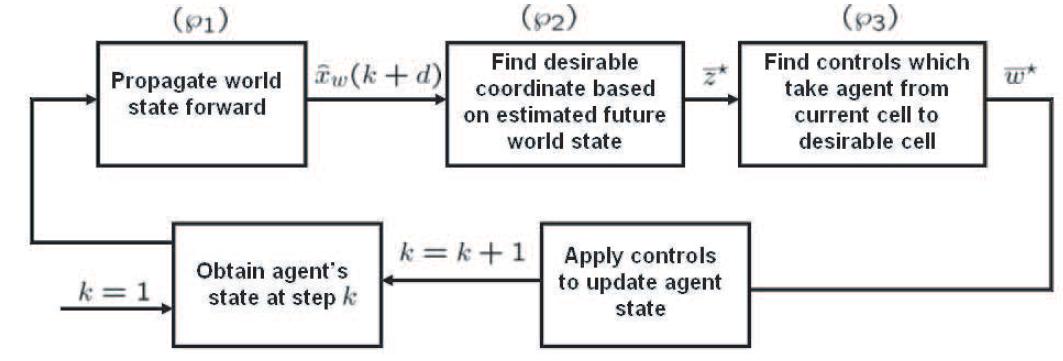

Figure 3: Single agent search strategy

The search algorithm is modular in the sense that it is comprised of three main steps. Each step is somewhat independent of the others and different algorithms can

be used to accomplish the same goal within any of the three main steps. The first step involves propagating the world state (the occupancy map) forward in time.

By providing a predictive aspect to the problem, each agent can then make control decisions based on the predicted future state of the world rather than only using

the current information. Once the system generates a predicted future world state, each agent determines a desirable coordinate to visit in the future. The desirability

of a location is measured using a complex objective function. This formulation allows for each agent in the team to have a different set of parameters and therefore,

each agent can have its own notion of desirability. Finally, once this desirable coordinate is determined, a path through the environment that transitions the agent from

its current location to the desirable coordinate can be applied.

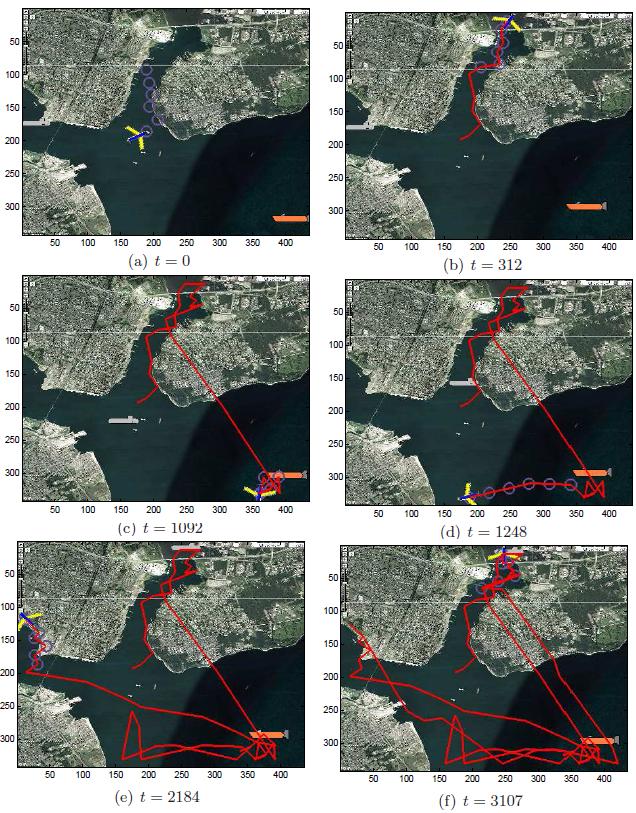

Figure 4: Agent patrolling harbor in New York using single agent search strategy

Human-in-the-Loop Simulation

A large part of the research in this dissertation is directed toward the development of algorithms that govern the actions of a single UAV or a team of UAVs

at an abstract level. These algorithms apply to other unmanned vehicles as well. These algorithms govern high level behaviors such as task and path planning,

but we assume that low level algorithms already exist to handle tasks such as state stabilization and signal tracking.

The end goal for many of these algorithms is fully autonomous behavior without input from human operators. However, there are many benefits for allowing

human interaction with the system. Verifying and validating a fully autonomous algorithm through an unmanned flight test requires significant logistical

planning and development. Many other UAV subsystems that are not directly related to the core strategic algorithm must be developed in order to support

the mission. Furthermore, these autonomous flight tests must be conducted in controlled airspaces and under strict supervision. All of these factors greatly

increase complexity and development time of the overall system. Many of these problems can be addressed simply by introducing human decision making and

interaction at very specific points in the system.

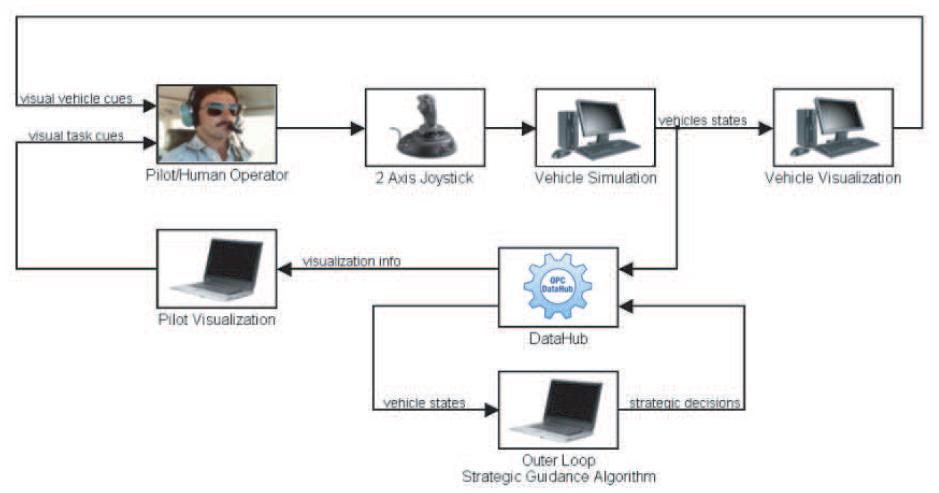

This chapter investigates a ground based, distributed testing environment which is used at the Autonomous Flight Systems Laboratory to test high level

algorithms by using a human operator in place of several low level systems. In this fashion, the overall system operates in a manner very similar to

the fully autonomous system. This approach offers many benefits. The main advantage is that the high level algorithms can be implemented and tested

much faster and with significantly less effort. In addition, applications can be developed for a standard Windows based environment instead of embedded

real time systems. Furthermore, the algorithms can be tested in unrestricted airspace due to the fact that they are operating as a pilot-assistance system

which the pilot is free to ignore at any point.

The main drawback with this architecture is the introduction of a human operator or pilot who may behave in a non-deterministic fashion. To alleviate

this problem, a distributed ground based simulator is used to train potential pilots to interact efficiently and consistently with the system.

Figure 5: System architecture for ground based distributed human-in-the-loop simulation

Flight Testing

The last step in the verification and validation process of the autonomous algorithms involves a real time flight test. This chapter describes the various

components necessary for the flight test. This section investigates the hardware used during the setup and how it integrates with the overall system architecture

described previously. The setup and experimental methodology of the test are detailed in the full dissertation.

Figure 6: Flight test hardware

References

-

C. W. Lum, "Coordinated Searching and Target Identification Using Teams of Autonomous Agents"

PhD Dissertation University of Washington,

March 2009 [.pdf]

-

C. W. Lum, R. T. Rysdyk, and J. Vagners, "A Search Algorithm for Teams of Heterogeneous Agents with Coverage Guarantees"

Submitted to the AIAA Journal of Aerospace Computing, Information, and Communication [.pdf]

-

C. W. Lum, R. T. Rysdyk, and J. Vagners, "Rapid Verification and Validation of Strategic Autonomous Algorithms Using Human-in-the-Loop Architectures"

Submitted to the AIAA Journal of Aircraft [.pdf]

-

C. W. Lum and J. Vagners, "A Modular Algorithm for Exhaustive Map Searching Using Occupancy Based Maps"

Proceedings of the AIAA Infotech@Aerospace Conference,

April 2009** [.pdf]

-

C. W. Lum and R. T. Rysdyk, "Feature Extraction of Low Dimensional Sensor Returns for Autonomous Target Identification"

Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference,

August 2008 [.pdf]

-

C. W. Lum, M. L. Rowland, and R. T. Rysdyk, "Human-in-the-Loop Distributed Simulation and Validation of Strategic Autonomous Algorithms"

Proceedings of the AIAA Aerodynamic Measurement Technology and Ground Testing Conference,

June 2008* [.pdf]

-

C. W. Lum and R. T. Rysdyk, "Time Constrained Randomized Path Planning Using Spatial Networks"

Proceedings of the AACC American Control Conference,

June 2008 [.pdf]

-

C. W. Lum, R. T. Rysdyk, and A. Pongpunwattana, "Occupancy Based Map Searching Using Heterogeneous Teams of Autonomous Vehicles"

Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference,

August 2006 [.pdf]

|