Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Healthcare for Indigenous Veterans | References

Hilaria Supa Huamán – Leadership Qualities

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Lakota Education | References

Brave

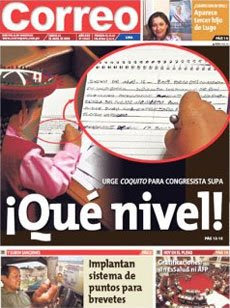

Hilaria Supa boldly perseveres in her activism despite the constant criticism and barriers she has faced, truly embodying bravery. While she experienced violence, racism, and sexism, she confronted these and rose above the challenges to international prominence. In the late 1990s she protested the forced sterilization of Indigenous women. Government officials, including President Alberto Fujimori and local Health Ministry doctors either denied that it occurred or argued it was beneficial for the “family planning” of Indigenous families. Even other Indigenous leaders criticized Supa’s role in opposing this crime. Hilaria Supa showed resilience in the face of these protests, struggling for months so those affected could get the compensation they deserved. In 2006 she was elected to the Peruvian Congress. As a result, she received many negative comments, specifically ones directed towards her lack of formal education and her L2 Spanish abilities. However, she responded diligently, describing the experience of her youth and early adulthood and its impact on her education and opposing the racist tone in these criticisms. Additionally, she took her oath in Quechua, which grew the anti-Indigenous sentiments that came with her election. Congresswoman Martha Hildebrandt criticized Supa saying that Spanish should be the only language used in Congress. Further verbal and visual harassment, such as racist depictions of Indigenous peoples, reached a national audience on television. We choose this quality because Hilaria Supa bravely faced a racist and sexist society, surmounting every challenge to articulate the rights and desires of the Indigenous peoples of Peru.

Strong-willed

Hilaria Supa exemplifies a strong-willed leader. From her earliest activism, she never took no for an answer. Despite living in a patriarchal and racist society, she fought to give the peasant and Indigenous women of Anta province a voice, creating and leading movements and organizations such as the Federation of Peasant Women of Anta (FEMCA) to defend their common interests. She understood where colonial modes of relations were harmful and criticized the prevailing culture that contributed to alcoholism, malnutrition, domestic abuse, and financial instability. She also pushed for a return to traditional knowledge in a society that outright rejected Indigenous foods, medicines, and farming techniques. Furthermore, Hilaria Supa’s strong will enabled her to push through her disabilities to benefit the society that surrounded her. She has suffered from arthritis since her early life but that didn’t stop her activism. In her memoir, Supa recalled travelling on horseback to remote villages, sleeping in the cold, and relying on local charity in order to spread her messages of women’s rights, peasant’s rights, and Indigenous rights. Hilaria Supa’s strong-willed nature ties in directly with her bravery, as both enabled her to face the challenges of an oppressive system and work for a more free and equal society.

Empathetic

Hilaria Supa has taken on an active role in an attempt to restore justice to the indigenous peoples of Peru. Hilaria’s mission is based on empathy and her fight for the indigenous people was fueled by personal experience. With her political platform she continues to shine the spotlight on the neglected and marginalized Native communities. Hilaria empathizes with the people she fights for because she, too, had grown up with a background of poverty, Spanish as a second language, and no formal education. Also having experienced sexual assault from her husband, Hilaria felt compelled to take on more roles for Indigenous women’s organizations and to educate Peruvian women, Quechua or not, on abuse and domestic violence. When Hilaria urged the Peruvian government and the UN to stop the encroachment of Indigenous lands, promoted education for indigenous people, and exposed the illegal sterilization of Indigenous men and women, it showed her desire for equality for the peasants and Indigenous peoples. When Hilaria learned of the racist sterilization practices, she lobbied for women to be compensated. She assisted these women in their battle against the corrupt dictatorship of Alberto Fujimori because she knew what it was like to be seen as a second-class citizen. We know that empathy fuels connection, it allows us to experience the emotions of others on their level and to be able to feel their feelings with them, and that is exactly what Hilaria did when she met with the peoples she fought for and listened to their concerns.

Hilaria Supa Huamán – Biographical Timeline

John Trudell – Biographical Timeline

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson – Leadership Qualities

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Colonial Gender Violence | References

Brave

Leanne Simpson has created a wide range of literature and research addressing numerous amounts of issues within Indian country. Her discussions touch on issues that are often overlooked or internalized within Indian country. She pushes the envelope and shows true fearlessness by addressing issues that are further perpetuated within the community by the community. For instance, Simpson addresses the damaging effects of heteropatriarchy within Indigenous communities by “queering resurgence”. Leanne has created dialogue that provides a voice for Native women and two-spirit/queer Indigenous folks. In Queering Resurgence: Taking on Heteropatriarchy in Indigenous Nation Building, she addresses and dissects the the topic of involving more Native women in nation-building. Simpson explains that hearing the statement “we need more women involved in nation-building” sounds like an effort to improve the community on the surface, but this statement invalidates the immense amount of work and leadership roles that Indigenous women have been involved in for centuries. Leanne fiercely addresses issues that other Indigenous leaders do not prioritize or dissect. Many Indigenous leaders focus on the battle with dismantling and decolonizing the damage solely caused by the colonizer but fail to address the toxicity that exists within these communities that are further perpetuated by community members. Leanne bravely critiques the patriarchal tendencies engrained into Native communities in efforts to further decolonize and build relations. She provides a voice for community members that are marginalized within their own communities. In many cases there are situations where colonial patriarchy and community power dynamics can be disguised as traditional and cultural practices. Simpson provides examples such as, the perpetuation of colonial gender roles, pressuring women to wear certain articles of clothing in ceremonies, the exclusion of LGBTQ2 individuals from communities and ceremony, the dominance of male-centered narratives regarding the Indigenous experience, and the lack of recognition for women and LGBTQ2’s voices, experiences, contributions and leadership. Leanne Simpson shows true bravery by fighting for the interrogation of heteropatriarchy to become a part of Native communities decolonizing project. Her speech is radical and defies some extreme traditionalist’s beliefs and practices and forces communities to acknowledge their lack of inclusivity, patriarchal, and heteronormative tendencies that are normalized and engrained into community practices and protocols.

Visionary

Leanne Simpson throughout her life has continued to maintain focus on her vision of reforming the social issues of First Nations. She has strategically put her efforts in areas she deems will result in the greatest aid to her cause. This includes participating in the Idle No More movement and attempting to help gender-based violence and protect indigenous homelands by revisiting Canada’s Indian Act. Simpson also helps to turn her ambitions into reality through other means that may seem unorthodox relative to physically protesting/reforming. Simpson holds a PhD from the University of Manitoba and has written numerous novels (Islands of Decolonial Love, Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back, The Gift is in the Making, etc.) that educate the common reader on Indian traditions, customs, and oppression. The philosophy she attempts to spread is contrary to that of “extractivism”, which is the removal of Earth’s natural resources, assimilation of Natives, the removal of Indigenous ideals, and cultural appropriation. Through her protests and novels she attempts a resurgence in Indigenous ideology, intelligence, and community.

Creative

Leanne Simpson is a renowned Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg artist, musician, poet and writer, who has been widely recognized as one of the most compelling Indigenous voices of her generation. Her work intersects between story and song, bringing audiences into a rich and layered world of sound, light, and sovereign creativity. Her latest album, f(l)ight, was released in 2016. f(l)ight is a collection of story-songs that effortlessly interweaves Simpson’s complex poetics and stories of the land, spirit, and body. Simpson’s work breaks open the intersections between politics, story and song. Leanne Simpson creates work that is a form of activism and resistance, addressing issues such as discrimination within her community. She created a music video for her song-poem “Leaks” from the album Islands of Decolonial Love. The video is shares the story of a young Anishinaabekwe experiencing racism for the first time, the poem is the voice of the mother realizing that she cannot protect her daughter from such injustices and acts of hate, but she can influence her in healing from these experiences. The video shows visuals of Leanne with her daughter on the land of the Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg. The film is about living as an Anishinaabekwe, displaying the powerful connection to the land and the importance of passing that knowledge down to future generations. She states in the poem, “you are not a vessel for white settler shame”, teaching her daughter to take pride in her Indigenous identity and the importance of decolonizing her self-image. The poem and visuals are a notion of resistance, teaching her daughter to find healing through her land relations and cultural practices.

Katie John (Athabaskan) – Leadership Qualities

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Atlantic Salmon | References

Strong-Willed

Strong-Willed is great word to use to describe Katie John. She was raised in an environment that many would not be able to withstand. Substance living is arguably one of the best ways for both personal health and the health of the planet. However, substance living requires strong people because it is not easy.

She learned English as a teenager. Learning a new language past the age of ten is proven to be far more difficult than when a child. She was married young and raised so many children. She then helped create a written alphabet for the language that she was raised with. Part of her being strong-willed is the will to keep her language alive, while so many factors of western culture is trying to erase it.

To credit her will once again, she started a court case to have Alaska state permit substance fishing. She was determined and fought for this for the remainder of her life. A huge part of her culture and the way she was raised is substance living. Once again Western culture tries and eliminate an indigenous culture, Katie John saw it as her duty to keep her language and way of living still going.

Frank

John did not mince words, beat around the bush, or play games. Throughout her life, she spoke plainly and directly about the issues she fought for and against. It did not matter who you were, what your status was, or what you thought of her, Katie John just told you what she thought. This was apparent in her leadership in Mentasta Village, where she once told her own son and other tribal members that they had to leave the village for a certain amount of time, and could not come back until they changed their ways.

Further, when she went to the Supreme Court to fight for substance rights, she did not change the frank way in which she talked, and in fact, seemed to utilize it as a way to break through the formal barriers of the court. After the court case had been determined in favor of her and the tribe, then Governor Tony Knowles could have appealed on behalf of the state of Alaska, and she simply invited him to their fish camp, which was illegal at the time. They spent the day together, and she spoke in her frank manner about the importance of fish to her people and their way of life. However, this is not to say she spoke with humor, or without intelligence, and when the Governor accidentally let a fish fall back into the river, she asked if he had granted it a “gubernatorial pardon.”

Determined

Being that Katie John was well known for obtaining rights for her people, it is clear to see that this job was not easy. Challenges she faced, especially that of being a Native woman, come to show how determined she was when standing up for what she believed in. Katie John knew well what things to take in consideration that would potentially be both positive or negative, but did not let that stop her from reaching her goals.

Katie received many rejections over the period of years in which she fought for her and her peoples rights, that including the one towards the Alaska Board State of Fisheries. This movement that began in 1985 by Katie herself, continues up to this day, even after her passing. This comes to show that although what she fought for was what she believed to be their rights, she was determined to do this not only for the period of time in which she lived, but for the future of her people. Despite many obstacles Katie faced while trying to obtain their rights, she did it all with love and honor and did not stop fighting up until her last days, making her a very respected Native American woman.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson – Colonial Gender Violence

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Colonial Gender Violence | References

During the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) special chiefs gathering in Gatineau, Québec in early 2016, the Liberal leader announced that his government had begun the process to create the inquiry into the nearly 1,200 indigenous women and girls who have been murdered or who have gone missing in Canada over the past three decades. Across Canada, activists, aboriginal leadership and many of the families of missing or murdered Aboriginal women have been calling for a national inquiry for more than a decade. First Nations Communities have been seeking to ensure a safe and violence-free future for all Aboriginal bodies across Canada. The previous Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, failed to take any action to investigate these decades of genocide towards First Nations Canadian women and Two-Spirit people. It is critical for our Canadian Government to consult with victims’ families and Aboriginal leaders to gather the views of our First Nations people on the design, scope, and parameters of the full inquiry of the murders and missing First Nations women across Canada. Aboriginal women make up just 4% of Canada’s female population but constitute the staggering rate of 16% of all women murdered in the country. First Nations, Inuit and Metis women are three times more likely to report experiencing violence. The Canadian justice system itself is responsible for perpetuating violence against Aboriginal bodies and has been set up to serve a society built on Indigenous erasure. Law enforcers are often the offenders/perpetrators of these crimes committed.

Leanne Simpson addresses this epidemic of colonial gender violence throughout Indian Country in Not Murdered, Not Missing: Rebelling Against Colonial Gender Violence. Simpson begins by explaining, “White supremacy, rape culture, and the real and symbolic attack on gender, sexual identity and agency are very powerful tools of colonialism, settler colonialism and capitalism, primarily because they work very efficiently to remove Indigenous peoples from our territories and to prevent reclamation of those territories through mobilization. These forces have the intergenerational staying power to destroy generations of families, as they work to prevent us from intimately connecting to each other. They work to prevent mobilization because communities coping with epidemics of gender violence don’t have the physical or emotional capital to organize. They destroy the base of our nations and our political systems because they destroy our relationships to the land and to each other by fostering epidemic levels of anxiety, hopelessness, apathy, distrust and suicide. They work to destroy the fabric of Indigenous nationhoods by attempting to destroy our relationality by making it difficult to from sustainable, strong relationships with each other.” Leanne then suggests that it is in our best interests to approach this issue of gender violence as a core resurgence project, a core decolonization project, a core of any Indigenous mobilization. She makes it clear that she is addressing violence against all genders, including the high rates of violence perpetuated against two-spirit/queer Indigenous bodies. Women and Two-Spirit/LGBTQ2 peoples are both at higher risks of being subjected to violence within the structure of settler colonialism. Leanne breaks this down by explaining that one of the many tactics of the colonizer is to use gender violence to remove Indigenous peoples and their descendants from the land, then remove agency from the plant and animal worlds and re-positioning the land as a resource to be used by the colonizer.

Leanne Simpson then states that movements such as Idle No More, where women are on the front lines cannot be used to abolish this violence. Throughout history and continuing to present day, we see that gender violence is the colonial response to Indigenous resistance. Simpson creates a consensus to avoid putting Indigenous women leaders and activists at risk when working to eliminate this violence. Leanne Simpson states, “We must build criticality around gender violence in the architecture of our movements. We need to build communities that are committed to ending gender violence and we need real world skills, strategies and plans in place, right now, to deal with the inevitable increase in gender violence that is going to be the colonial response to direct action and on going activism. We need trained people on the ground at our protests and our on the land reclamation camps. We need our own alternative systems in place to deal with sexual assault at the community level, systems that are based on our traditions and do not involve state police and the state legal system. Her end goal is working towards building Indigenous communities where all genders stand up, speak out and are committed to both believing and supporting survivors of violence and building Indigenous transformative systems of accountability. The answer is within the community to work to protect its women and two-spirit members, we cannot look to the state which is the largest perpetrator of gendered violence to solve this issue.

On speaking out about Gender Violence towards Indigenous women, Leanne Simpson claims that the situation is infuriating. Simpson views the situation as one that impacts every Indigenous person. Leanne Simpson states, “It ends here for Loretta, Bella and all of the other brilliant minds and fierce hearts we’ve lost. It ends here. This is my rebellion. This is my outrage. This is the beginning of our radical thinking and action.” Simpson knows that her reactions to such an event are driven on pure emotion but she is diplomatic- using emotion to drive her activism home when it comes to gender violence. Simpson educates and explains why everyone should feel upset and horrified at the murders. She gives her audience the room to become emotional and driven to make a change in a society where emotional involvement is invalidated.