Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Sixties Scoop Settlement | References

Louis Riel exemplified a myriad of impressive characteristics. Specifically, he sought to preserve the culture of the Métis. He did so by persevering through uprisings, and strategically fighting against the Canadian Government to better the lives of his fellow Métis.

Preserver of Culture

Riel sought to preserve Métis rights and culture as their homelands in the Northwest came progressively under the Canadian sphere of influence. Riel was an intelligent leader who fought to protect the social, cultural and political status of the Métis in Red River and the Northwest more generally. As tensions mounted among the Métis in 1869 it was clear that strong leadership was needed, and Riel had leadership coursing through his blood. Although Riel’s experiences growing up produced a lifestyle quite different from that of the traditional, buffalo-hunting Métis, it was these people he aspired to lead. He struggled not only for himself but for his people. Riel fought for the Métis and their rights to own land. He battled an unreasonable and irresponsible government while protesting central Canadian political and economic powers. After leading the Métis and bringing Manitoba into Confederation, it is clear that Riel struggled for the Métis, the people of Manitoba and the Northwest. By leading the Métis in a time of economic, political, and cultural turbulence, he was able to provide the nation with a sense hope, strength, and pride. Riel’s execution made him the martyr of the Métis people; he is a heroic rebel who fought to protect his people from the unjust encroachments of an Anglophone national government. It is more than clear that Riel was a rebel with a cause, fighting to preserve his people’s culture and rights.

Persevering

Riel’s perseverance is apparent throughout his career as both a politician and a rebel leader. Despite being threatened by high-ranking government officials, Riel never faltered in his attempts to achieve justice for his fellow Métis. After being convicted by the Canadian government for the murder of Thomas Scott, a warrant was issued for Riel’s arrest and he was exiled to Montana for five years. Although he was in exile during the important governmental elections of 1872 and 1873, Riel was determined to provide a voice for his people. Despite his naturalization in the United States, Riel continued to uphold his status as an influential indigenous individual by fighting against alcoholism within indigenous communities and again campaigning for another governmental institution. Despite gaining a U.S. citizenship and settling down in Montana, Riel valiantly gave up his life in the states when he was appointed to lead the Métis people who were left in distress back in Saskatchewan.

Not long after his return to Canada, Riel issued a Bill of Rights to Imperial Ottawa consisting of the grievances and the compensations the Métis deserved. Although these grievances were neglected by Prime Minister John Macdonald, Riel did not lose hope and continued fighting for the rights of Métis people. He pursued his quest for justice by creating the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan and actively rebelling against the Canadian government in hopes of regaining native rights. As a young man, Riel embodied perseverance as he fought for his fellow Métis; he exemplified this characteristic up until the moment he was hanged. Riel was passionate about the Métis people and believed that they had a right to their freedom, to own property, and to be separate from Canada’s dominion government.

Strategic

Before Louis Riel’s more militant and rebellious approach towards the maltreatment of his fellow Métis, he pursued a more diplomatic alternative to violence. Riel pinpointed unjust governmental actions towards his people and combined his personal vision with a national vision to form the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan. With the provisional government, Riel was able to officially represent his people in the eyes of the public. He filed the Manitoba Act, which stated that Métis lands would be protected, but all other lands were to remain the property of the Dominion of Canada. This act marked the legal resolution of the struggle for self-determination between the Métis and the federal government.

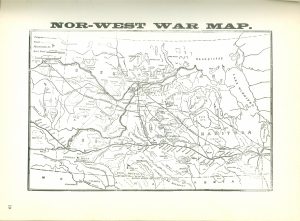

After returning from his exile in 1884, Riel’s first course of action was to collect all the grievances and requests of Métis, half-blood farmers, and prairie natives to be condensed into a Bill of Rights where settlers demanded that they be given title to the lands they occupied, that the districts of Saskatchewan, Assiniboia, and Alberta, be granted provincial status, that laws be passed to encourage the nomadic Indians and Métis to settle on the land, and that the Indians be better treated. After the petition was neglected by Prime Minister Macdonald, Riel retaliated by seizing a church in Batoche, making it both a jail and a storehouse, a tactical move that proved a useful advantage in the fight. While capturing the Church, Riel also strategically cut telegraph lines between cities to delay the notice of the rebellion to the dominion government, providing his rebel forces with more time to effectively retaliate. Familiar with the unsettling outcomes of other native groups who were oppressed in North America, and aware that his more peaceful forms of protest were not effecting change, Riel resorted to war. He sought to strategically help the Métis and other Indigenous groups, whether it be through diplomatic acts or rebellions, Riel acted upon the government’s negligence and fought for the rights of his people.