Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | OK Tribal Gaming Dispute | References

Neville Bonner – Mauna Kea

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Mauna Kea | References

Mauna Kea is a dormant shield volcano located in Hawaii, with the tallest summit in the region at almost 14,000 feet above sea-level. Mauna Kea is considered a sacred place for the native people of Hawaii, because of it’s many sites of natural and cultural significance such as traditional cultural properties, buildings and trail systems. The land is rich with objects of cultural significance that maintain the cultural identity of the Hawaiian community.

In addition to Mauna Kea’s cultural significance to Native Hawaiians, the land is also known for being the optimal spot for astronomers to stargaze and conduct research due to its high elevation, unblemished air, and distance from any cities. In addition to objects and sites of cultural significance, Mauna Kea is also home to many observatories and telescopes owned and operated by eleven different countries.

In 2014, there was a proposal for a new telescope to be constructed on the summit of Mauna Kea, the $1.4 billion Thirty Meter Telescope. When/if built, this telescope would be the most powerful and advanced optical telescope on the planet. However, the plan has been received with much opposition from Native Hawaiians who refer to Mauna Kea as the core of their culture. At 18 stories tall 1.4 acres wide, the Thirty Meter Telescope would be another tarnish to a sacred, ancient landscape which holds cultural significance dating back hundreds of years. To the Native Hawaiians, the construction of the telescope represents the recurring issue of indigenous land rights and whether these scientists have a right to build this telescope on their sacred land in the first place. After Hawaii was annexed to the United States, there was a boom of development on Hawaiian land, which contributes to the lack of credibility in the U.S. government’s promise to preserve and protect Hawaiian land currently.

On the proposed first day of construction, peaceful protest ensued on Mauna Kea’s summit and has persisted ever since. As of today, the telescope has not been built, but scientists are lobbying for its completion. However, some scientists are divisive about the issue as well, stating that although the telescope would be extremely critical in advancing astronomical research, they themselves do not have the right to develop on the sacred mountain. Protesters currently are hoping the court case opposing the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope reaches the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, the developers claim to be on track to completion by 2024.

Regarding this event, Neville Bonner would support the Native Hawaiian’s peaceful protest against the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope in Mauna Kea. During his time, Bonner was supportive of Aboriginal activists when they utilized their right to express themselves and speak against the injustices Aboriginal peoples faced. However, Bonner would believe that utilizing political methods would be far more effective than a peaceful protest. Instead of directing his attention onto the scientists, Bonner would face the white government who has the final say on constructing the Thirty Meter Telescope to show that indigenous peoples are capable of doing more than protests. He believed that the best way to bring change to the Aboriginal community was to reform the oppressive political system. Bonner would show the U.S. government that indigenous peoples’ rights are to be honored and given the proper political support. To the non-indigenous politicians who do not understand indigenous cultures, Bonner would speak for the spiritual relationship indigenous peoples had with their lands. Only in the government would he have the opportunity to push the issue and force the non-indigenous politicians to listen to the problem involving Mauna Kea, because it is they who wield the power in constructing the Thirty Meter Telescope.

During his life, Neville Bonner was an advocate for indigenous rights, especially land rights. As the chair of the Select Committee on Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, he recommended better protection of Aboriginal sacred lands, as well as the exclusive use of certain lands for Aboriginal communities. Therefore, he would recommend the same to the United States government. Mauna Kea is a sacred land of cultural significance and importance to the Native Hawaiians. Therefore, Bonner would uphold the belief that the United States has a duty to protect these lands, rather than destroy them by building the Thirty Meter Telescope. Bonner would also advocate that Mauna Kea originally belonged to the Native Hawaiians, and therefore the Native Hawaiians currently retain ownership of such lands. Even though Hawaii was annexed by the United States, Bonner would avidly oppose the theft and destruction of sacred Native Hawaiian lands.

Ely S. Parker – Maori Land Ownership

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Maori Land Ownership | References

The Maori people are indigenous Polynesians currently facing land ownership issues in their home of New Zealand. Between 1250 and 1300 CE, settlers from the Polynesian islands began to make canoe voyages to New Zealand, where they developed into a distinct culture. Europeans arrived In the 17th century. Initially, relations between the Maori and Europeans was amicable, but the Europeans were eager to claim this land for their own. In 1840, after years of negotiations with the indigenous people on the island, the Europeans and Maori leaders signed the Treaty of Waitangi. This treaty established British governance over the island and gave the Maori people the full rights and privileges of British subjects. Most importantly, it guaranteed full ownership of the Maori lands, forests, fisheries and other possessions. The treaty made both parties happy at first, but disputes over the wording of the English and Maori versions of the treaty have lead to problems of land ownership in New Zealand. Since the treaty was established, Maori land has frequently been sold without its peoples discretion. This problem continues today.

In 2004, the New Zealand parliament passed the Foreshore and Seabed Act, which granted the ownership of the intertidal zones all around the island to the government. This zone held plentiful natural resources, such as fish, that the government wanted to sell for extra money. The Maori people, however, had been using those lands since they arrived in the 13th century, so under the treaty, they were rightfully the owners of this land and thus it was illegally claimed by the government.

This act has been protested by the Maori since 2004, and in 2009 the act came under official review and revision. Revisions were put into the Marine and Coastal Area (Takuti Moana) act of 2011. This act made the coastal land public again, and also gave the Maori the right to claim ownership of the land under two conditions. The people had to prove they were holding the land in accordance with their customs, i.e. they were engaged in traditional fishing tactics and generally not abusing the land, and they also had to prove that they have occupied the area from 1840 to now without substantial interruption. Obtaining and presenting this proof to the government was and still is difficult, and thus many people have lost the lands their families have lived on for many generations, despite the fact that the treaty of 1840 granted them full rights.

If Ely S. Parker were alive today and serving the New Zealand government instead of the US, he would have greatly opposed the 2004 FAS act and would have upheld the Treaty of Waitangi. He would have endeavored to make sure that no Maori people would have their land illegally claimed and sold away.

Parker valued fairness above everything else, and at all times in his life sought to uphold the law of the United States. He saw ratified treaties as the final word on disputes, regardless of the contents of the treaty. When Native Americans or white politicians attempted to change treaties, Parker followed the Supreme Court decision of Fellows vs Blacksmith, which stated that a treaty, once ratified, had to be followed whether the Native Americans had knowingly assented or not. In the case of the FAS act, Parker would maintain that the treaty had to be followed, whether whites liked it or not.

Parker was also a pragmatist. He valued the continuation of Native peoples and communities, but he was flexible about methods. He would be eager to support the diversification of Maori incomes, so they were not reliant on fish. As he provided Native tribes with farm equipment and training, he would seek to provide the Maori with resources that would allow them to leave the shore behind. Currently, the Maori use the intertidal zones for fishing, gathering seaweed, travel, and burial grounds. They have a long cultural connection to the land. Parker did not spend much time worrying about cultural heritage. In his early career, he supported land allotments and removal of Native Americans in an effort to compromise. Later in life, he regretted his strong stances on both matters, realizing that many Native Americans had stronger connections to their land than he did. Depending on when in time he was asked about the FAS act, his views on it would evolve.

No matter Parker’s views on the nuances of FAS, he would still uphold the Treaty of Waitangi. He followed the law at all times, carefully overseeing his position as Commissioner of Indian Affairs and taking great pains to keep everything in order. He would never have allowed his own government department to cheat indigenous people out of their land.

Louis Riel (Métis) – Biographical Timeline

Chief Leschi – Schaghticoke Nation Lawsuit

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Schaghticoke Nation Lawsuit | References

In October of 2016 the Schaghticoke Tribal Nation filed a lawsuit against the State of Connecticut claiming the state unlawfully seized the nation’s land and has profited from since 1801 without properly compensating the tribe. The suit is seeking compensation from the state to the tune of $610 million and announcing the tribe’s intention to seek restoration of its federal recognition that was granted in 2004 then revoked the following year.

In 1736, the Colony of Connecticut established 2,400 acres of land in its northwest corner along the border with New York as a reservation for the Schaghticoke people. The state is required to act in the best interest of the Schagticoke people in managing the tribe’s land (which is held in trust by the state for the tribe) and funds as per statutes dating as far back as 1757. Between 1801 and 1918, the state sold or in other ways profited from portions of the reservation promising to compensate the tribe, and today, only 400 acres remain in the hands of the Schaghticoke Tribal Nation. Both the constitution of the United States and of the State of Connecticut mandate proper compensation for any and all land seized by the government, but to this day no compensation has been given to the Schaghticoke people for the 2,000 acres stolen from them. The State of Connecticut is likewise required by Connecticut law to render an annual accounting of the funds of the Schaghticoke Tribal Nation and any profit made from their lands–a mandate that has been similarly ignored.

Were Chief Leschi still alive today, he would certainly not stand for Native lands being stolen and not properly paid for. It is likely that he would even go a step further and demand the return of the land itself and not just compensation. This is a motion the Schaghticoke Tribal Nation has attempted to no avail. In 2010, the Schaghticoke Tribal Nation filed a land claims action for the return of 2,100 acres of the stolen land–the majority of which remains undeveloped and sparsely populated. This suit, however, was dismissed by the Second United States District Court in light of the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ reasoning for revoking the tribe’s federal recognition in 2005–a move resulting from a massive lobbying campaign by members of the government of Connecticut that began when the tribe was granted federal recognition in 2004. The Schaghticoke Tribal Nation appealed the ruling to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals which upheld the District Court’s ruling whereupon the tribe appealed their case to the United States Supreme Court which denied to review the decision.

This assessment of Leschi’s view is based on his actions with regards to the Medicine Creek Treaty and his stand that the Nisquallies be granted proper land–not merely the leftover scraps proposed in the treaty. The negotiation process and treaty terms were rife with grievances against the Native representatives. Washington Territorial Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Isaac Steven expressly instructed the interpreters to only communicate in the crude trade language of Chinook Jargon (a language with only five hundred words and unsuited for negotiating the complex language of treaties) and not the full language in which the representatives were fluent, Lushootseed. Stevens arrived at the negotiating table with a pre-drawn treaty and, by most accounts, strong-armed the Native representatives into signing instead of listening to their perspective and negotiating terms that fit their needs. Yet, Leschi, a man with a reputation for level-headedness and a renowned moderator, was willing to look past these and plenty other grievances, but he would not waver on securing a proper land deal for his people.

The 1854 treaty granted the Nisquallies a reservation of 1,280 acres made of the least desirable land that could be found along the Puget Sound. It was made of densely forested rocky hillsides and marshy shoreline unsuitable for farming with no access to the rich prairie land or Nisqually River from which Nisquallies drew most of their food and wealth–not to mention their name which literally translates to “people of the grass country.” Accepting these terms would have meant relegating his tribe to dependence on outside forces as the vast majority of the land that enabled Nisquallies’ self-sufficiency and livelihoods was being stripped away. Such an arrangement was so unacceptable for Leschi that there are several accounts claiming he stormed out of the negotiations without signing the treaty and that his signature was forged. The subsequent war that erupted the following year in 1855 between United States forces and several tribes around the South Puget Sound area under Leschi’s leadership forced Governor Stevens back to the negotiating table. New reservation lines were drawn giving both the Puyallup and the Nisqually greatly expanded borders on much more productive and desirable land–one of the very few instances in United States history whereupon a war with Native Americans resulted in better treaty terms for the Native Americans.

Considering his determination to prevent his people from essentially getting ripped off and to defend their ability to function as a sovereign nation, and the fact that, of everything in the negotiation process and treaty terms that could cause grievance, it was the land issue that drew the greatest opposition and resistance from Leschi, were he alive today he would in no way stand by and permit the State of Connecticut to break their own laws in order to unjustly (and unlawfully) steal land from the Schaghticoke Tribal Nation.

Katie John (Athabaskan) – Leadership Qualities

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Atlantic Salmon | References

Strong-Willed

Strong-Willed is great word to use to describe Katie John. She was raised in an environment that many would not be able to withstand. Substance living is arguably one of the best ways for both personal health and the health of the planet. However, substance living requires strong people because it is not easy.

She learned English as a teenager. Learning a new language past the age of ten is proven to be far more difficult than when a child. She was married young and raised so many children. She then helped create a written alphabet for the language that she was raised with. Part of her being strong-willed is the will to keep her language alive, while so many factors of western culture is trying to erase it.

To credit her will once again, she started a court case to have Alaska state permit substance fishing. She was determined and fought for this for the remainder of her life. A huge part of her culture and the way she was raised is substance living. Once again Western culture tries and eliminate an indigenous culture, Katie John saw it as her duty to keep her language and way of living still going.

Frank

John did not mince words, beat around the bush, or play games. Throughout her life, she spoke plainly and directly about the issues she fought for and against. It did not matter who you were, what your status was, or what you thought of her, Katie John just told you what she thought. This was apparent in her leadership in Mentasta Village, where she once told her own son and other tribal members that they had to leave the village for a certain amount of time, and could not come back until they changed their ways.

Further, when she went to the Supreme Court to fight for substance rights, she did not change the frank way in which she talked, and in fact, seemed to utilize it as a way to break through the formal barriers of the court. After the court case had been determined in favor of her and the tribe, then Governor Tony Knowles could have appealed on behalf of the state of Alaska, and she simply invited him to their fish camp, which was illegal at the time. They spent the day together, and she spoke in her frank manner about the importance of fish to her people and their way of life. However, this is not to say she spoke with humor, or without intelligence, and when the Governor accidentally let a fish fall back into the river, she asked if he had granted it a “gubernatorial pardon.”

Determined

Being that Katie John was well known for obtaining rights for her people, it is clear to see that this job was not easy. Challenges she faced, especially that of being a Native woman, come to show how determined she was when standing up for what she believed in. Katie John knew well what things to take in consideration that would potentially be both positive or negative, but did not let that stop her from reaching her goals.

Katie received many rejections over the period of years in which she fought for her and her peoples rights, that including the one towards the Alaska Board State of Fisheries. This movement that began in 1985 by Katie herself, continues up to this day, even after her passing. This comes to show that although what she fought for was what she believed to be their rights, she was determined to do this not only for the period of time in which she lived, but for the future of her people. Despite many obstacles Katie faced while trying to obtain their rights, she did it all with love and honor and did not stop fighting up until her last days, making her a very respected Native American woman.

Katie John (Athabaskan)- Biographical Timeline

Carl Gorman (Navajo) – Bear Ears National Monument

Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Bear Ears National Monument | References

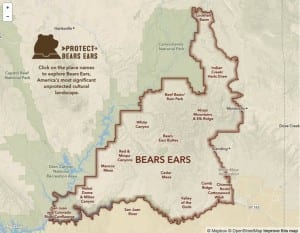

President Trump recently announced to reduce the size of the Bear Ears National Monument and the Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah by 85 percent. On December 4th, 2017, Trump gave back about two million acres of land back to the local officials. This will open the sacred Native American lands and forested highlands to oil and gas drillers, coal and uranium miners, and to build more roads. By doing so, Trump pleased small government and business proponents in Utah. The ancient artworks at Bear Ears National Monument will be destroyed along with the area’s ancient Native American petroglyphs. Bears Ears holds great cultural significance to the Navajo and Hopi tribes, as well as the Zuni Pueblo, the Ute Mountain Ute, and the Southern Ute tribes. This reduction represents the largest decrease of federal land protection in US history and could threaten the area’s tribal culture.

The monuments were preserved under the efforts of President Obama and President Clinton, but these efforts will be erased due to the reductions signed by President Trump. The monuments in Southern Utah have long been opposed by state leaders. Obama and Clinton created them under the Antiquities Act, which gives presidents authority to unilaterally protect any federally owned area from development, with few restrictions. President Obama said the monuments were meant to safeguard “important cultural treasures, including abundant rock art, archaeological sites, and lands considered sacred by Native American tribes.” Though Trump disagrees with that and thinks that the past democratic administrations have severely abused the purpose of the century-old law, Antiquities Act.

Although Trump’s actions can expand the economy, he faced immediate backlash from environmentalists and American Indian tribes who say his actions threaten sensitive and culturally significant areas. Bear Ears houses some of the oldest Native American rock paintings and engravings. All of which are very fragile and without the protection of the government, they will be destroyed. Many Native Americans believe that their heritage is traded for short term corporate profits. A group of five native tribes along with 13 environmental organizations have filed suit against the Trump administration to protect these monuments. Legal experts say that the Antiquities Act gives presidents authority to create national monuments, but does not give them the power to cut or abolish them altogether. Boundaries of national monuments have been modified more than 80 times since congress created the Antiquities Act and no group has fought against it in court, so this will the be first time.

Even though majority of Native Americans and environmentalists are against Trump’s actions, there are still a handful of Native Americans who applaud Trump’s move. About two percent of Navajo’s are in support of Trump’s administration to slash the monuments. The southeastern part of Utah has about 31 percent poverty rate and a median income about 24 percent lower than the national average. The believe that by wiping out the monuments, more job opportunities would be available through cattle farming, ranching, mining, and logging.

If Carl Gorman were still alive today, he would certainly not stand for their scared land to be given back to the government for economic gain. He would stand by his tribe and environmentalists to protest Trump’s actions. Gorman would use his status as a prominent artist and professor at UC Davis to speak out against the stolen land. This assumption is speculated because Gorman was a Indian artist himself. After World War II, Carl attended Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, California. He was a proud Navajo who used his art to express and showcase his history and traditions. Throughout the rest of his life, he continued to paint. His interests with Navajo culture led him to manage the Navajo Arts and Craft Guild and Direct the Native Healing Sciences with the Navajo Nation. Gorman also became a professor at University of California Davis focusing on Native Art. It can be seen that throughout his life, whether it was during WWII or post-war, he was a proud Navajo. His interests in art was also clear. With that being said, because of his love of art and cultural appreciation, he wouldn’t want Bear Ears National Monument to be decreased by 85%. With him being an art lover, he certainly would not want the ancient rock work and history to be destroyed. He would hope they can be preserved and appreciated forever.