Biographical Timeline | Leadership Qualities | Lakota Education | References

Background

Most Americans agree that obtaining a post-secondary education is essential to a brighter future. However, the Eurocentric education system of the United States has failed Native students and is not suited for their success. An important factor behind Native students not excelling in the education system is the terror and shame inflicted on Indigenous peoples, because the schooling for Native children is used as a weapon to further coerce assimilation.

One tribe in particular, the Lakota, on the Sioux reservations of the Oglala and Pine Ridge, the effects of colonization and intergenerational trauma are still prevalent today. Contributing to the high rates of incarceration, suicide and use of drugs and alcohol. Sadly, the life expectancy of Lakota men is only 48 years old. Though most of these issues are in response to the Relocation Acts the US government forced upon previous generations, where Natives were encouraged to leave their reservations and create lives in bigger cities. However, the Relocation Act possessed an unrealistic optimism and didn’t address issues like racial discrimination or segregation. This act destroyed and disrupted Native Culture, eventually leaving Natives homeless and struggling. The Relocation Act of 1956 is a major contributor to the high number of Native Americans living off the reservations.

On average, according to the Bureau of Indian Education, 90 percent of Native students attend public schools off the reservation. In these public schools, white students are twice as likely to succeed than Native students. When students lack the basic resources offered to every other community, it hinders the progress that they are able to make. When it comes to graduation, only 70 percent of the students graduate. A large number of Native students are left feeling invisible and their dream of going to college is not in the near future. Action is needed for the Lakota, because half of their population is under the age of 25 and the overall mental health of the students is declining.

Resilience

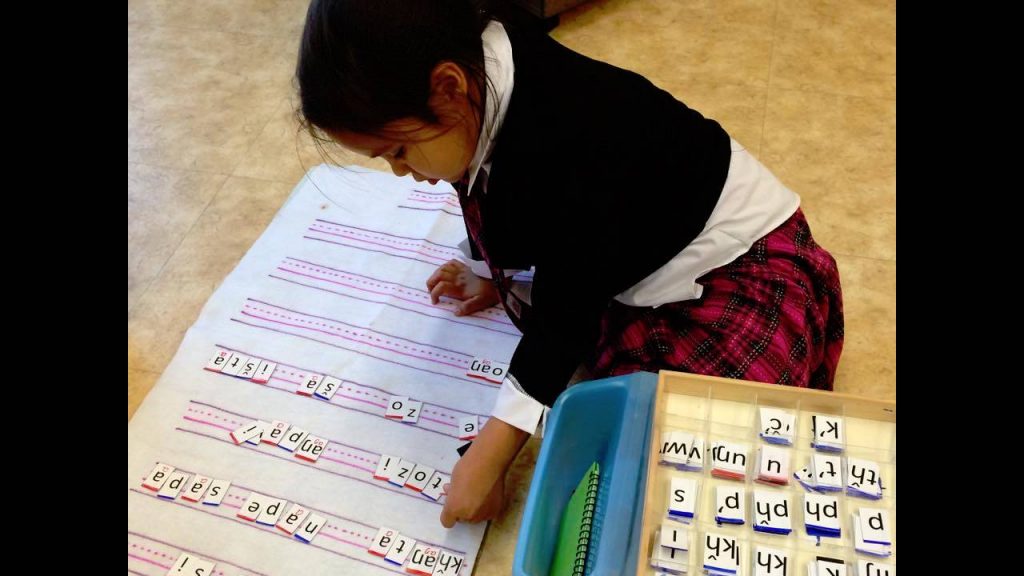

Despite these statistics, there are Lakota students who show their resilience by continuing their education. Some have been accepted into prestigious colleges like Yale University, for example. Along with the increasing numbers of teens attending college, a school called “Red Cloud Indian School” offers students an alternative option for school, focusing on the Lakota culture, teachings, and language. At Red Cloud High school, the students are required to take 4 years of Lakota language. Also, the National Indian Education Association has been able to create a plan with state education to consult with tribes on the needs of tribal students. Aside from the state education, within the public schooling, schools have been implementing and evaluating Native language immersion. NIEA has also offered schools for additional funding for drop-out prevention, and mental health services. The Lakota community approves of the immersion of culture into the schools because it offers economic and social contributions.

Hilaria’s Position

Hilaria Supa Huamán, a Quechua Peruvian activist and politician, is recognized for her part in the fight for the rights of Indigenous peoples. Being an Indigenous person, practicing her traditional ways and speaking her Native language of Quechua, she understands the importance of one’s culture. One of Hilaria’s core issues is the fight for Indigenous and peasant education rights.

Hilaria would agree that the United States school system is suited for white students to succeed, while the lack of resources for Native students keeps these communities in a vulnerable position. Vulnerability is enshrined in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia where Chief Justice John Marshall deemed Indians not as foreign nations, as previously stated in the Constitution’s Commerce Clause, but instead as “domestic dependent nations.” This kept the tribal nations dependent on the federal government. Forms of dependency are displayed in the education structure today, like the allocation of fewer funds to low socio-economic schools creating a need for more federal funding. It appears that the federal government’s intent was to create reliance by Natives, in a ward-guardian relationship, in order to maintain control over Indigenous peoples.

It appears that Hilaria would lobby for more federal funding for public schooling in the lower socio-economic Indigenous communities in order to create a more equal learning experience. For the Lakota in particular, Hilaria would emphasize the importance of integrating the traditional Lakota culture for the students and allocate funds for culturally relevant activities like after school programs but also culture programs during regular school hours. When it comes to the organization of the social structure in schools, I feel that she would assist the schools in creating models of education for the students which were not based off of the colonial mindset but rather change the focus toward a more matriarchal societal structure. She might begin an outreach program for Native girls, much like her organization FEMCA, to inform the girls about their heritage, to encourage them to learn and practice their ceremonies, and to help them understand that they are the bearers of culture. As President of the Education Commission, she worked tirelessly for the education rights of the Quechua, and she would most likely do the same for the Lakota.