The Natural History of National Identity in Russian Landscape Painting

James West, University of Washington

The history of both European and Russian landscape painting provides many striking examples of a phenomenon that might be called 'partly projected landscapes' - not the wholly imaginary landscapes that were especially popular in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, but the projection onto actual scenes of a vision, driven by philosophy or fashion or both, of what artist and public alike wished to see in a landscape. In Russia, from quite early in the eighteenth century until well into the second half of the nineteenth, the tension between reality and vision is complicated by a parallel phenomenon, the attachment of content to technique: Russian painters learned landscape techniques from the example of Europe, whether formally through art academy training, either in Russia or in Europe itself, or informally by example from collections of European landscapes in Russia. In Russia both landscape composition and the rendering of landscape details reflected, in obvious or more subtle ways, the scenes painted by European masters, and native Russian scenes often seem to have been refracted through a vision of the landscape of Italy, the Netherlands, France or Britain. The distinctly European-looking scene above left is a painting by Aleksei Voloskov of Marienhof, a country estate close to St. Petersburg. As the national self-awareness of Russian painters intensified from the late eighteenth century through the first half of the nineteenth, the desire to make Russian landscapes unmistakably Russian led many painters to introduce identifiably Russian details into their canvases: people and their dress, artifacts and vehicles, buildings and other structures, and characteristic topographic features. There is nothing unusual about the introduction into landscapes of such national 'signifiers': this was only what landscape painters of most European countries had done at one time or another over the previous two or three centuries.

The history of both European and Russian landscape painting provides many striking examples of a phenomenon that might be called 'partly projected landscapes' - not the wholly imaginary landscapes that were especially popular in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, but the projection onto actual scenes of a vision, driven by philosophy or fashion or both, of what artist and public alike wished to see in a landscape. In Russia, from quite early in the eighteenth century until well into the second half of the nineteenth, the tension between reality and vision is complicated by a parallel phenomenon, the attachment of content to technique: Russian painters learned landscape techniques from the example of Europe, whether formally through art academy training, either in Russia or in Europe itself, or informally by example from collections of European landscapes in Russia. In Russia both landscape composition and the rendering of landscape details reflected, in obvious or more subtle ways, the scenes painted by European masters, and native Russian scenes often seem to have been refracted through a vision of the landscape of Italy, the Netherlands, France or Britain. The distinctly European-looking scene above left is a painting by Aleksei Voloskov of Marienhof, a country estate close to St. Petersburg. As the national self-awareness of Russian painters intensified from the late eighteenth century through the first half of the nineteenth, the desire to make Russian landscapes unmistakably Russian led many painters to introduce identifiably Russian details into their canvases: people and their dress, artifacts and vehicles, buildings and other structures, and characteristic topographic features. There is nothing unusual about the introduction into landscapes of such national 'signifiers': this was only what landscape painters of most European countries had done at one time or another over the previous two or three centuries.

However, the focus here is on the more difficult task which many Russian artists of the second half of the nineteenth century set themselves: to impart national characteristics to a pure landscape that contains no tell-tale elements of a specific human culture. Examples of attempts to do this can be found in both European and American painting, but in 'The Age of Tolstoy' there was a particularly determined effort on the part of some Russian painters to present a national landscape based primarily on geography, flora and fauna. Although in a few cases the plants and animals in question were seldom seen outside Russia, in most cases they had a more generally European distribution, but were characteristic 'climax species' in Russia, familiar to all, and often of emblematic significance in Russian popular culture and folklore. This tendency was especially marked in the always somewhat nationalistic realism of the peredvizhniki, their contemporaries and some of their successors, and it appears to have reflected a conscious effort to counteract the homogenizing effect of the application of generally European landscape painting techniques and styles to the Russian scene. This essay introduces some of the issues surrounding what might be termed 'biological nationalism' in Russian landscape painting, and focuses for illustration mainly on Ivan Shishkin, who provides the clearest, but certainly not the only examples.

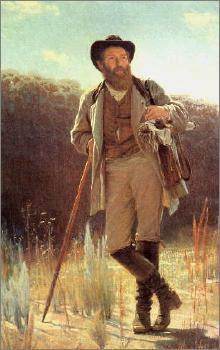

The trend towards biologically accurate landscapes in this period was not confined to Russia and the peredvizhniki: it was a European and American phenomenon, too, and it was fueled by the knowledge painters had of the natural history of the plants and animals they chose to portray. This knowledge had its roots, of course, in the scientific discoveries of the seventeenth and even earlier centuries, but in the nineteenth century two socio-cultural factors in particular brought it to the fore. One was the European-wide enthusiasm for the study of 'Natural History' in a time when the subject had a central place in both the typical secondary school curriculum and the fashionable leisure pursuits of educated people. The other was the enthusiasm for hunting (especially intense among Russians, and not only of the gentry class) and angling, which called for a particular kind of applied natural history: a knowledge of the habitat and behaviour of the quarry, be it fish, flesh or fowl. In his Preparing for the Hunt (1836) [Illustr. 1] Evgraf Fedorovich Krendovsky depicts himself and four of his pupils, and leaves little doubt as to whether Russian artists shared in this particular source of knowledge of the countryside.

Beyond noting that landscape painters were likely by virtue of their education to have at least a basic knowledge of the biology of what they painted, something needs to be said about an aspect of the overall culture of Europe in the relevant period that is very relevant to the type of landscape discussed here, but has received oddly little attention from art historians: the culture of Natural History and the other fields of study that were associated with it.

By the end of the eighteenth century, educated Europeans shared a prominent scientific or quasi-scientific interest not just in the biological environment, but in several subjects thought of as more or less closely related: living flora and fauna, but also palaeontology; local history, but also archaeology; geography, and also geology, as they related to local topography and the local economy; and  'curiosities' - anything egregiously out of the ordinary. The basic study of these subjects was embedded in the curriculum of secondary schools, both public and private, and of universities and 'academies'. It was established, distributed and coordinated through the work of 'Natural History Societies' and 'Field Clubs' that brought amateurs and professionals together, the amateurs often assisting in the researches of the professionals, at least as collectors in the field, and extending them into provincial areas far from the main centers of learning. The societies and clubs published their findings in journals or volumes of transactions, and comprehensive natural histories of particular countries or regions became a popular genre for the educated public, often reinforcing national or regional pride in the unique characteristics of a distinctive environment. Though written for the lay reader, these volumes were intended to provide the beginnings of serious and comprehensive scientific education: they covered the obscure and the invisible as well as the more obvious and ubiquitous forms of life, they introduced the reader to the systematics of living things, employing Latin as well as vernacular names, and they most often included instructions on acquiring or improvising the equipment needed for serious amateur field work, including microscopy and, in the second half of the century, photography. However, even well into the twentieth century, popular education in biological science was often placed in the context of the underlying - and in this period unavoidable - theological issues. The philosophical and theological mindset of the early explorers of ever smaller details of nature made exploration of the microcosm another face of the exploration of the macrocosm. Minutely detailed exploration of the structure of living things was not for them a self-sufficient activity: it was an attempt to answer questions about the cosmos and how the divinity had created it, with the hope of solving riddles that were ultimately religious and spiritual in nature. The pervasive mathematization of the life sciences and their pursuit in a climate of dispassionate objectivity is a phenomenon of the second half of the twentieth century, even if its seeds lie earlier, and projecting this perspective onto the biology of the nineteenth and earlier centuries leads to serious misunderstandings. As late as the early twentieth century, the business of Natural History still retained some of its earlier religious character, with educated churchmen playing a major role in the dissemination and even the generation of natural history and biological knowledge. In Britain, a well-known example is Canon S. N. Sedgwick's widely read The British Nature Book, a comprehensive field-guide covering representative species of the entire animal and plant kingdoms with their scientific names, including sections on practical field work and equipment, which was still in print in 1931. Sedgwick prefaces his manual with a five-page introduction reassuring his young readers that Darwin's account of the evolution of species is fundamentally sound and not incompatible with the teachings of the church, or even the language of the Book of Genesis. [1] To appreciate the intellectual climate in which the Natural Sciences were pursued in the nineteenth century, the cultural historian needs to step away from the present-day perspective and be aware of what occupied the minds of Newton, Linnaeus and Darwin besides what they are chiefly remembered for today. [2] One further widespread component of nineteenth-century thought is important to an understanding of the culture that produced the 'biological landscapes' of the Age of Tolstoy: the idea that the character of a people is closely related to the natural environment in which its culture has developed. This idea was born in the Enlightenment but nurtured through the Romantic revolution and brought to fruition by Hippolyte Taine in the second half of the nineteenth century. The celebrated and influential Russian historian Ivan Egorovich Zabelin has been credited with introducing a similar idea to the circles in which Ivan Shishkin moved: "… the landscape of a country always has a profound and irresistible influence on both the thinking and the poetic sensibility of a people…" [3]

'curiosities' - anything egregiously out of the ordinary. The basic study of these subjects was embedded in the curriculum of secondary schools, both public and private, and of universities and 'academies'. It was established, distributed and coordinated through the work of 'Natural History Societies' and 'Field Clubs' that brought amateurs and professionals together, the amateurs often assisting in the researches of the professionals, at least as collectors in the field, and extending them into provincial areas far from the main centers of learning. The societies and clubs published their findings in journals or volumes of transactions, and comprehensive natural histories of particular countries or regions became a popular genre for the educated public, often reinforcing national or regional pride in the unique characteristics of a distinctive environment. Though written for the lay reader, these volumes were intended to provide the beginnings of serious and comprehensive scientific education: they covered the obscure and the invisible as well as the more obvious and ubiquitous forms of life, they introduced the reader to the systematics of living things, employing Latin as well as vernacular names, and they most often included instructions on acquiring or improvising the equipment needed for serious amateur field work, including microscopy and, in the second half of the century, photography. However, even well into the twentieth century, popular education in biological science was often placed in the context of the underlying - and in this period unavoidable - theological issues. The philosophical and theological mindset of the early explorers of ever smaller details of nature made exploration of the microcosm another face of the exploration of the macrocosm. Minutely detailed exploration of the structure of living things was not for them a self-sufficient activity: it was an attempt to answer questions about the cosmos and how the divinity had created it, with the hope of solving riddles that were ultimately religious and spiritual in nature. The pervasive mathematization of the life sciences and their pursuit in a climate of dispassionate objectivity is a phenomenon of the second half of the twentieth century, even if its seeds lie earlier, and projecting this perspective onto the biology of the nineteenth and earlier centuries leads to serious misunderstandings. As late as the early twentieth century, the business of Natural History still retained some of its earlier religious character, with educated churchmen playing a major role in the dissemination and even the generation of natural history and biological knowledge. In Britain, a well-known example is Canon S. N. Sedgwick's widely read The British Nature Book, a comprehensive field-guide covering representative species of the entire animal and plant kingdoms with their scientific names, including sections on practical field work and equipment, which was still in print in 1931. Sedgwick prefaces his manual with a five-page introduction reassuring his young readers that Darwin's account of the evolution of species is fundamentally sound and not incompatible with the teachings of the church, or even the language of the Book of Genesis. [1] To appreciate the intellectual climate in which the Natural Sciences were pursued in the nineteenth century, the cultural historian needs to step away from the present-day perspective and be aware of what occupied the minds of Newton, Linnaeus and Darwin besides what they are chiefly remembered for today. [2] One further widespread component of nineteenth-century thought is important to an understanding of the culture that produced the 'biological landscapes' of the Age of Tolstoy: the idea that the character of a people is closely related to the natural environment in which its culture has developed. This idea was born in the Enlightenment but nurtured through the Romantic revolution and brought to fruition by Hippolyte Taine in the second half of the nineteenth century. The celebrated and influential Russian historian Ivan Egorovich Zabelin has been credited with introducing a similar idea to the circles in which Ivan Shishkin moved: "… the landscape of a country always has a profound and irresistible influence on both the thinking and the poetic sensibility of a people…" [3]

We should turn now to the link between art and what is widely referred to as 'the culture of natural history', a link that derives from the need for copious illustration of the life sciences in the age of the collecting box and the microscope. Illustration was of course necessary for purposes of scientific recording and systematic identification , but it also satisfied another purpose: the presentation of plants, animals and all the 'curiosities' of nature as objects of admiration, with the art of the engraver and colourist as another object of admiration in its own right. It was artists who produced the volumes of botanical and zoological prints that popularized the work of the biologists, but it is very important to acknowledge that, in the educational climate of eighteenth and nineteenth century Europe, the distinction between professional artist and professional biologist was often blurred, particularly in the case of botany, and there is more to the connection than just the aesthetic of the botanical print. The botanical prints of Germany, France and Britain, widely disseminated throughout Europe, including Scandinavia and Russia, have a direct relationship to the study of plants by landscape painters in the period we are dealing with. In the first place, they were a great deal more than just a permanent record of the identifying features of a living plant [Illustr. 2: Aegopodium podagraria (Goutweed, Ground Elder), UK, Sept. 2004]: for this function, nothing could replace the herbarium specimen. [Illustr. 3, Note 4: Aegopodium podagraria, the specimen in Linnaeus' herbarium] The botanical print aimed to illustrate the plant more completely, to show its characteristic structure and growth, with marginalia illustrating its minute and microscopic parts, and, in a miniature work of art, the impression it made on the eye of the admiring botanical observer [Illustr. 4: Aegopodium podagraria, print from G. H. von Schubert's Naturgeschichte des Pflanzenreichs, 1854]. At the extreme of this tendency, botanical illustrations became quite elaborate: they might include a group of species from the same environment, and even an element of the appropriate landscape. A late 19th-century coloured print of Feathergrass (Stipa pennata) on a Russian steppe [Illustr. 5] provides a perfect demonstration of the distance between the fully-realised botanical illustration and the basic herbarium specimen [Illustr. 6, Note 4: Stipa pennata, the specimen in Linnaeus' herbarium]. The nineteenth-century culture of botany had a dual focus: the scientific recording of plant species both local and exotic, and the depiction of them, often in their natural environments, for their aesthetic appreciation. This culture sometimes had a visible effect on landscape painting of a certain kind. Turner is celebrated for paintings that capture the interaction of light and terrain, and convey the overall texture of a landscape by almost impressionistic means. [Illustr. 7: J.M.W. Turner, The Upper Falls of the Reichenbach (1802)] On the other hand, his watercolour of The Crook of the Lune, looking towards Hornby Castle [Illustr. 8], painted between 1816 and 1818, is an example of another kind of landscape that was in Turner's repertoire. It is the sweeping view that is a Turner hallmark, but it is unusually finely detailed, and the foreground corners contain particularly detailed shrubs, roots and plants. There is a reason for this: it is one of a series of twenty watercolours commissioned by Dr Thomas Dunham Whitaker, 'antiquarian and topographer', to be engraved as plates for The History of Richmondshire, published by Longman's between 1819 and 1823. English county 'histories' in the nineteenth century typically gave at least as much space to the natural history of the county as to its history in the more usual sense. In other words, the context of this watercolour is not the mainstream of nineteenth-century landscape painting as such, but a different genre that belongs within the aesthetic of bio-geography: high-quality illustrations of the topography and natural history of areas of the country whose educated populace took a pride in the distinctive natural environment of their native region. The aesthetic of landscape painting is blended here with that of maps, 'prospects', and botanical prints and engravings. Interestingly, Ruskin, in the Age of Tolstoy, praised this watercolour for its "fidelity to the minutiae of nature." [5]

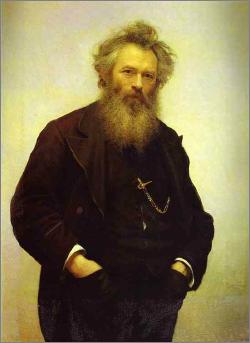

How does Ivan Shishkin, the leading Russian practitioner of the biologically accurate landscape, fit into this picture? Though he was born into a provincial Russian merchant family, Shishkin's education was not very different from that of many basically schooled but more extensively self-taught men and women who became artists with a biological bent - or biologists with an artistic bent - in Europe. Natural History had a secure place in the curriculum of Russian gimnazii, both public and private, and even seminaries, whose aim was to educate children for more walks of life than just the priesthood. [6] The curriculum for Russian secondary education was in fact established by a set of rules and edicts promulgated very early in Alexander I's reign, in 1803 and 1804, in comprehensive detail that included elaborate instructions for the field trips on which the teacher of Natural History was to take his pupils. [7] This curriculum had changed little by the 1840s, when Shishkin attended the boys' gimnaziia in Kazan' for four years - paradoxically, it was not until later in the century, when Shishkin was in his prime, that the place of Natural History in the curriculum was sharply reduced in favour of Classical languages. Perhaps more importantly, Shishkin's father was a self-taught but widely-read local historian and antiquarian with an interest in all aspects of the Elabuga region, who plied his son with reading materials and encouraged his natural inclination to study a range of subjects. Later, in the diary he kept during his stays in Germany and Czechoslovakia as an art student, Shishkin leaves hints that his art studies were accompanied by at least some study of the natural history of the new environments in which he found himself. On 11 July 1862, during a prolonged stay in Prague, he writes of a visiting Czech friend: "Yesterday Kolar and I worked on botany, he keyed out the plants he had collected, and we also worked with the microscope." On 15 July: "Jakobi arrived this morning from Dresden; we visited the museum again, and saw some manuscripts and books with miniatures by Czech artists, but there was a particularly rich collection of geological specimens, a lot of impressions of prehistoric plants." [8]

How does Ivan Shishkin, the leading Russian practitioner of the biologically accurate landscape, fit into this picture? Though he was born into a provincial Russian merchant family, Shishkin's education was not very different from that of many basically schooled but more extensively self-taught men and women who became artists with a biological bent - or biologists with an artistic bent - in Europe. Natural History had a secure place in the curriculum of Russian gimnazii, both public and private, and even seminaries, whose aim was to educate children for more walks of life than just the priesthood. [6] The curriculum for Russian secondary education was in fact established by a set of rules and edicts promulgated very early in Alexander I's reign, in 1803 and 1804, in comprehensive detail that included elaborate instructions for the field trips on which the teacher of Natural History was to take his pupils. [7] This curriculum had changed little by the 1840s, when Shishkin attended the boys' gimnaziia in Kazan' for four years - paradoxically, it was not until later in the century, when Shishkin was in his prime, that the place of Natural History in the curriculum was sharply reduced in favour of Classical languages. Perhaps more importantly, Shishkin's father was a self-taught but widely-read local historian and antiquarian with an interest in all aspects of the Elabuga region, who plied his son with reading materials and encouraged his natural inclination to study a range of subjects. Later, in the diary he kept during his stays in Germany and Czechoslovakia as an art student, Shishkin leaves hints that his art studies were accompanied by at least some study of the natural history of the new environments in which he found himself. On 11 July 1862, during a prolonged stay in Prague, he writes of a visiting Czech friend: "Yesterday Kolar and I worked on botany, he keyed out the plants he had collected, and we also worked with the microscope." On 15 July: "Jakobi arrived this morning from Dresden; we visited the museum again, and saw some manuscripts and books with miniatures by Czech artists, but there was a particularly rich collection of geological specimens, a lot of impressions of prehistoric plants." [8]

Shishkin's contemporaries - friends and family, teachers and students - frequently referred to his study of the forests that were his favourite subject, and his legendary insistence on accuracy in portraying them, but Shishkin does not seem to have been involved with an existing culture of natural history in quite the same way as Turner, who sometimes placed his artistic talent, through commissions, at the service of those whose business was to record the scenery and wildlife of a region. He appears rather to have set out to create such a culture within the realm of landscape painting itself, recording in meticulous detail a type of Russian landscape that seemed to him to epitomize the nation as a whole. But there is plentiful evidence that even the many who admired him did not quite understand what Shishkin was doing, and there is an often encountered notion that Shishkin's passion for detail cost him something in expressing the emotive appeal of the scenes of Russian nature that he painted. I. N. Kramskoi, in a letter to F. A. Vasil'ev on 5 July 1872, wrote that Shishkin "amazes us with his knowledge", and when he is working from nature he is in his element. "But when something else is needed, then… You know. I think he's the only one among us who has really made a study of the landscape, in the best sense, ... But he doesn't have those spiritual nerves that are so receptive to the sound and the music in nature, and are particularly active not when they're occupied with form and the eyes see it, but, on the contrary, when nature is not before one's eyes, and there remains the general sense of things, the dialog among them and their real significance in the life of the human spirit, and when a real artist under the influence of nature generalizes his instincts, and thinks in dots and tones and carries them to the kind of vision that only needs them to be formulated in order for him to be understood. Of course, people understand Shishkin: he expresses himself clearly and makes an irresistible impression, but how fine it would be if he also had a vein in him that could turn itself into a song." [9] This seems an oddly harsh judgement of an artist who worked as passionately as Shishkin did to 'get the scene right', and to make it possible for the trees and plants of his beloved forests - his Russia - to sing their own song. It is in fact an indication of the extent to which the origin of Shishkin's painterly vision lay in a naturalist's approach to the natural world, combining scientific study with aesthetic appreciation, that was perhaps already beginning to seem old-fashioned. As we move on to look in more detail at some of Shishkin's work, it must be emphasized that it is wrong, or at least anachronistic, to assume that botanical and zoological exactitude must be dispassionate: that assumption reflects the misunderstanding of the climate of nineteenth-century natural history to which I made reference earlier. As a realm of scientific enquiry, Natural History was pursued both passionately, and with a strong component of aesthetic appreciation, and even a kind of moral duty, that lent themselves naturally to the expression of strongly-felt national and regional loyalties. Moreover, if botanical field-work was pursued with enthusiasm in Europe, it was pursued in Russia with the added passion of the hunt.

And yet the nature of Shishkin's realism is puzzling enough to need some further explanation. The claim that he practiced an almost photographic degree of realism in his landscape paintings has become a well-worn cliché, and the observation is not always intended as a compliment. We know that Shishkin spent a great deal of time looking at forest scenes and sketching them, we know he had his students learn basic drawing skills by working from photographs, some of them of his own paintings. It is probable that in the winter season he himself worked from photographs, and he is one of a number of  prominent Russian painters of his period who are said to have worked at one time or another as photo colourists (Kuindzhi was another). Was Shishkin's apparent hyper-realism linked to his interest in photography, and if so, how? The answer to this question goes to the heart of the problem of 'partly projected landscapes', and has to do with Shishkin's use of photographs as a study tool.

prominent Russian painters of his period who are said to have worked at one time or another as photo colourists (Kuindzhi was another). Was Shishkin's apparent hyper-realism linked to his interest in photography, and if so, how? The answer to this question goes to the heart of the problem of 'partly projected landscapes', and has to do with Shishkin's use of photographs as a study tool.

Where the study of the world of nature is concerned, the photograph injects a particular kind of visual truth into what the viewer sees. There is abundant experimental evidence of the extent to which the eye generally sees what the brain prompts it to see: in other words, sees what already makes sense to the viewer in some prior conception of how things ought to look. [10] But the camera, except when the photographer deliberately makes use of distorting techniques, registers a scene without subordinating the details to the overall picture, or one kind of detail to another. Moreover, when a photograph of normal dimensions is viewed, every part of the flat image is equally in focus: without changing the focal length of the eye, the viewer can see every detail represented in the photograph, whatever its distance from the observer in the original three-dimensional scene. Nineteenth-century artists and photographers, and members of the educated public, were aware of the peculiar quality of photographic images from the era of the Daguerreotype, even before the middle of the century. Early photographers, if they were not producing strictly utilitarian images, quickly developed a conventionally 'painterly' aesthetic where composition was concerned, but they also presented the problem of a very unpainterly uniform depth of detail, which flattened perspective and undermined some of the basic compositional techniques of painting. The earliest landscape photographs lacked a photographic equivalent of aerial perspective (the convergence over distance of colours, or shades of grey, into increasingly attenuated tones, with an accompanying decrease in definition of detail). The more sophisticated practitioners of Daguerreotype photography compensated for this effect by finding other ways to build depth into their images, most often by composing scenes in which perspective lines were artificially prominent, as in this c.1848 view of a street in Saint Pierre, Martinique, by an unknown French photographer [Illustr. 9, Note 11]. The building whose façade closes the far end of the street is as sharply detailed as the houses in the foreground, and the eye would perceive it almost in the same plane as the foreground if it were not for the converging perspective lines of the street. More importantly for our purposes, the uniformly detailed property of early landscape photographs made it difficult for the eye to edit the clutter, disorder and apparent lack of structure that are often characteristic of the natural world.

What lay behind Shishkin's passion for biologically exact detail was almost certainly not a simple quest for the ultimate in illusory realism. His most detailed paintings capture something of the sheer untidiness of a real forest, but they are none the less edited versions of the scene - and 'edited' in this context means 'structured'. It is much more likely that photographs helped him (and his students, whether or not they fully appreciated this) to find the true structure of the scenes to which he was drawn, a structure deeper than the conventional, simplistic vision of how forests and the plants within them grow - deeper, that is, than the conventions of landscape composition. Extensive landscape views, receding from the detail of the foreground into the vanishing simplification of the background, demand a structure, but have a way of suggesting naturally the handful of compositional clichés that have tended to dominate landscape painting throughout its history. Intensive landscape views, close-ups of a foreground so rich that it essentially precludes a background (which describes many of the paintings we are discussing) also demand a structure, but the artist who does not see all the living components of the scene and understand their organic relationship to each other will tend to impose one through simplification, at the risk of serious distortion of the essential nature of the scene as it would be perceived by a viewer who understood its biology. For this kind of view, photography helps the artist to find a structure in the complexity of the detail, rather than invent a structure through the selective omission of detail. The difference in approach can be illustrated by comparing a landscape painting with a naturalist's photograph of the same subject. The landscape artist sees the scene in its entirety: a grouping of trees, the water in which they are reflected, and the reed-bed that separates the trees from the water in a pleasing overall composition [Illustr. 10: Apollinarii Vasnetsov: Pond at Akhtyrka, 1880]. The naturalist sees the same scene as a number of distinct habitats, knows how its various components are ecologically related and what lives and grows in each micro-habitat, and will look at the scene one habitat at a time, with a more penetrating eye, from the perspective of biological rather than conventionally artistic structures [Illustr. 11: Reed-bed in a pond, USA, July 2004. The half-concealed bird is a sub-adult Green Heron (Butorides virescens )].

In the way in which Shishkin depicted the characteristic vegetation and the compositional structure of his intensive landscapes, the tension between the eye of the landscape painter and that of the naturalist can be illustrated by relating his paintings and studies to both photographs and botanical prints.

An obvious starting point is the depiction of Russian forests for which Shishkin is celebrated, and the details within them that he carefully explored. Forest in Mordvinovo (1891) [Illustr. 12] is a good example of the forest scenes by Shishkin that have always evoked amazement at the level of detail with which the painter has represented both the trees and the forest floor, with its preponderance of mosses, ferns and a few other characteristic plants. However, even if the scene looks 'wild' to the eye of most viewers, real forests of this type generally have a much less tidy structure, as a comparison with a photograph makes clear [Illustr. 13]. Shishkin did often include broken branches, fallen trees and forest debris in his paintings [Illustr. 14: Pine Forest (1885)], but even in these cases he introduced some compositional simplification into the scene as a camera would have recorded it. This occurred not just in the process of painting the scene, but sometimes before the painting even began. Kramskoi, for example, remembers Shishkin in 1872 preparing for one of his long sessions of working from nature by carefully rearranging the forest to his liking, clearing away undergrowth and breaking off intrusive branches [12]. Stands of water within forests had a particular appeal for Russian painters including Shishkin, and are the subject of several of his sketches, such as Over the Water (1880s) [Illustr. 15] and Pond (1870s) [Illustr. 16]. What is interesting about these sketches is that Shishkin appears to have 'edited' the scene, whether physically or in his imagination, to give the water more visibility: forest vegetation is characteristically denser in the vicinity of water, and forest pools are more typically overgrown, choked with trees and aquatic plants, and difficult to approach [Illustr. 17: WA, USA, 2004].

It is important to remember that wild as his forest scenes may appear, Shishkin, too, looked for some level of compositional simplification even as he was painting the vegetation with an unusual degree of attention to detail. However, what he sought was not the conventional compositional schemas of the extensive landscape: instead, he sought out the natural composition of the intensive landscape, the structures inherent in each of the living components of the forest or other natural scene. The plants and other details that he studied, sketched, and then included in his large forest canvases were predominantly those with a strong inherent structure of their own that would complement that of the trees.

Ferns feature frequently in Shishkin's forest-scapes. His Ferns in the Forest at Siverskaia (1883) [Illustr. 18] is a good example, and particularly interesting because the fern covering the forest floor is Pteridium aquilinum (Bracken, in Russian orliak ) which is primarily a plant of open heaths, and does not grow as commonly in woodland as species of the genus Dryopteris, such as D. filix-mas (Male Fern, Shchitovnik muzhskoi ) [Illustr. 19: UK, September 2004]. Shishkin did on occasion paint Dryopteris ferns, whose fronds emanate from a central rootstock, giving a structure that resembles a bunch of  feathers, but Bracken has a more satisfying tree-like structure, with several erect main stems from which the leaves branch out at intervals more or less horizontally. Shishkin's more open mixed woodland with an understory of Bracken gives the effect of one forest inside another, forming a 'nested' composition that is especially satisfying to the naturalist.

feathers, but Bracken has a more satisfying tree-like structure, with several erect main stems from which the leaves branch out at intervals more or less horizontally. Shishkin's more open mixed woodland with an understory of Bracken gives the effect of one forest inside another, forming a 'nested' composition that is especially satisfying to the naturalist.

Grasses are another type of erect plant that displays varied and attractive structures. A small painting by Shishkin, Birch and Rowan (1878) [Illustr. 20], portrays two less imposing trees in a setting that features grasses, which were presented in botanical illustrations no less attractively than the more showy flowering plants [Illustr. 21: Early 19th c. print of Festuca pratensis].

Fungi, too, exhibit pleasing structures [Illustr. 22: Lepiota cristata, USA, 2004], and were the subject of some of the most attractive botanical prints. Shishkin's sketch with the title A Thicket (1879) [Illustr. 23], aside from its similarity to Illustr. 20, is remarkable for the cluster of fungi in different stages of development in the lower left corner [Illustr. 24: Detail of Illustr. 22], which includes the white-spotted cap of what is probably the well-known and widely distributed Amanita muscaria, and mirrors the conventional depiction of fungi in botanical illustrations, whether in the ninetenth-century [Illustr. 25: 19th-c. print: Poisonous fungi, including Amanita muscaria] or in our own time [Illustr. 26: Beverly Hackett, Amanita muscaria (1978)]. In Illustr. 23, typically for Shishkin, the cluster of fungi that is so reminiscent of a botanical print is placed in a context of woodland, again adding a smaller to a larger structure. Shishkin exhibits the same predilection when he portrays another form of 'added structure': the bracket fungi that frequently grow on dead trees and felled stumps, as in his sketch entitled Felled Forest (1880s) [Illustr. 27]. One of the commonest and most widespread of such fungi, found throughout Eurasia and North America, is a familiar sight in a variety of forest environments [Illustr. 28: Ganoderma applanatum, USA, 2004].

In his Spider-web (1880s) [Illustr. 29] Shishkin portrays yet another frequently encountered forest sight that has a structural appeal: the web of an orb-weaving spider suspended as if by magic between sometimes astonishingly distant trees [Illustr. 30: Detail of Illustr. 27], an object which presents a challenge to the artist and even to the photographer [Illustr. 31: Suspended orb-web, USA, 2004. The web here is suspended not from the ferns visible in the background, but from the trunks and limbs of trees at a distance between 10 and 20 feet.].

The margins of forests are a distinct ecological zone, typically rich in flowering plants and shrubs that benefit from both full light and some of the shelter provided by adjacent trees. From the artist's point of view, they have a structure of their own, and Russian landscapists often depicted the vegetation of forest margins and adjoining meadows. Isaak Levitan's Meadow at the Forest's Edge [Illustr. 32] portrays a variety of meadow flowers against the dark background of a line of trees in a manner that is impressionistic, but conveys their structure quite accurately, with an identifiable Harebell (Campanula sp.) in the foreground. Shishkin's Flowers on the Forest's Edge. (1893) [Illustr. 33] also hovers on the borderline between impressionism and botanical accuracy, while his study A Forest Edge (1885) [Illustr. 34] is both more elaborate and more accurate.

More interesting still is the portrayal by Russian landscape artists of the commonest wildflowers and weeds for their own sake, in clusters that display their characteristic structure. Clustered weeds were a frequent subject of Shishkin's sketches and studies, such as Wildflowers (1884) [Illustr. 35] in which the dominant plant is a thistle (Carduus ?crispus). Such studies have a clear relationship to the long tradition of botanical illustration, which makes it all the more remarkable that Russian painters sometimes incorporated prominent clumps of humble weeds into otherwise quite conventional extensive landscapes. Arkhip Kuindzhi in his celebrated Morning on the Dniepr (1881) [Illustr. 36] has a thistle dominating from an elevated position a river view that stretches to a distant horizon. The flowers surrounding the foreground thistle are being visited by insects, including two butterflies [Illustr. 37]. The colourful butterfly on the right is identifiable as a Small Tortoiseshell (Aglais urticae, Russian krapivnitsa) [Illustr. 38, Note 13: Aglais urticae on Knapweed (Centaurea nigra), UK 2004], while the butterfly on the left can be recognized as most probably a Green-veined White [Illustr. 39, Note 14: Pieris (Artogeia) napi, Russian briukvennitsa, on Scabious (?Knautia sp.), UK, 2003]. In the immediate foreground of Morning on the Dniepr the white umbellifers with dark spots in the center of the umbel are easily identifiable as Wild Carrot (Daucus carota) [Illustr. 40], which is distinguished by one or two dark purple or wine-coloured flowers at the center of its otherwise white inflorescence. The butterflies in Kuindzhi's Morning on the Dniepr reflect the common practice of depicting insects on plants in botanical illustrations, and the beetles (Rhagonycha fulva) photographed on Wild Carrot in Illustr. 40 motivate that convention: feeding or pollinating insects are the rule rather than the exception on plants observed in natural surroundings. For Kuindzhi, it was apparently important that the butterflies and plants one might assume to be incidental details in his panoramic view of the Dniepr should be recognizable as particular, and familiar, species. Interestingly, insects are largely absent from Shishkin's work, and during his period of study in Switzerland, his friend Jakobi felt this lack keenly enough to amuse himself by adding them to Shishkin's sketches. [15]

Like Kuindzhi, Shishkin incorporated a stand of weeds into the foreground of one of his best-known extensive landscapes, Midday. Near Moscow (1869) [Illustr. 41], but it was more characteristic of his approach to landscape to focus on the intensive at the expense of the extensive setting. It is tempting to see something inherently photographic in this turning away from the more usual landscape vision, since the resulting effect is easily achieved in photography through a combination of camera angle, framing and cropping. In this simple example of a conventionally composed extensive view [Illustr. 42], an area of sky in the upper left quarter of the picture, bounded by a horizon of distant houses, is balanced by a clump of middle-ground trees and bushes in the upper right quarter, and a group of tall weeds anchors the foreground in the lower half. In a different cropping of the same exposure, the trees become a horizonless background, and the weeds become a thicket of wild carrot, thistles and grass, creating a composition that is different from that of the conventional landscape, but no less interesting: an aesthetically pleasing organic structure of interwined or superimposed botanical forms and textures [Illustr. 43]. The culmination of this approach for Shishkin was two studies of Aegopodium podagraria (Goutweed or Ground Elder; in Russian snyt') executed in the 1880s. Goutweed is planted in America as an attractive ground cover, but it is familiar in Russia and much of Europe as a persistent weed that is difficult to eradicate. The first of these studies [Illustr. 44] shows a patch of Goutweed in the well-lit angle between a wooden shed and a fence, with a glimpse of a more distant background beyond the trees behind the fence. In the second [Illustr. 45] the viewing angle is lower, and the background is closer, darker and denser, much of it consisting of an ill-lit fence that occupies the upper part of the canvas, with the comparatively well-lit Goutweed standing out against it. For the connoisseur of the Russian forest, weeds could become a miniature forest close to home.

What then made the biologically accurate landscapes of Shishkin and many Russian landscapists of his generation 'national'? The regional floras and faunas that are characteristic of northern Russia, including the forest floras, are neither unique nor confined to Russia, nor even restricted to the Palaearctic bioregion in general. Climax species are by definition widespread, and whole ecosystems can be closely similar in appropriate climates and geological conditions at similar latitudes across the world. A least in Europe, national identity is therefore seldom invested in particular species (though the Edelweiss in Switzerland and the Tyrol may immediately spring to mind, or the reindeer in Lapland and the extreme north of Siberia), and it is just as seldom invested in a particular mix of dominant species. Where plants are concerned, there are indeed rare endemics found only in restricted areas of Russia, including the areas in which Shishkin and others worked, but these are most often distinguishable from more common species only on close examination by a specialist, and they are not the plants that appear in the landscapes of Shishkin and his compatriots: it is the widespread climax species that feature in their paintings. Where animals are concerned, Ursus arctos arctos, the Eurasian Brown Bear, has more of a claim to be an emblem of the specifically Russian forest environment, as evidenced by the pervasive popularity throughout the twentieth century of Shishkin's Morning in a Pine Forest (1889) [Illustr. 46], which could be encountered from the cover of a third-grade school reader from 1960 [Illustr. 47, Note 16] to the pages of the satirical humor magazine Krokodil in the 1980s [Illustr. 48]. Even so, bears in a forest setting are not exclusively emblematic of Russia: they are to be found today throughout the relevant European ecological regions (formally, the Scandinavian and Russian Taiga and the Sarmatic Mixed Forests), including Eastern Europe and Northern Scandinavia, with isolated populations in the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Balkans and Greece. Meanwhile, the equivalent ecological region in the Nearctic has two closely related subspecies, U. a. middendorffi and U. a. horribilis, and an abundant population of the similar Ursus americanus, the American Black Bear, which despite its common name is as likely to be brown as black. Canada and the United States have bestowed on the bear at least as large a place in their popular visual culture as have the Russians, and given the strong similarity in the climax vegetation of the Russian and North American bear habitats, it would in fact be difficult to attribute an uncaptioned painting of bears in a boreal forest to the appropriate continent, unless the artist had included at least one plant, bird or animal that occurs on one continent but not the other, and portrayed it accurately enough to allow certain identification. In the case of plants, the indicator species would probably not be trees, colourful flowering plants or fungi, but obscure and less conventionally aesthetic components of the forest undergrowth, which a landscape artist would be tempted to treat impressionistically as background rather than depict in identifiable detail. As an example, in the densely forested foothills of the Cascade Mountains in Washington State, USA [Illustr. 49: bear habitat in Western North America], there is an abundant population of bears, and scenes like Shishkin's Morning in a Pine Forest are relatively commonplace. What betrays the location of this habitat is the prominent component of the forest understory in the foreground of Illustr. 49, Oplopanax horridus (Devil's Club), which does not occur in Eurasia [Illustr. 50, Note 17: Oplopanax horridus at close quarters]. There is a similar indicator in the background of Illustr. 22: not the fungus, which even when photographed at a range of a few feet cannot be unambigously distinguished from Lepiota species occurring in Russia, but the Western Sword Fern (Polystichum munitum) that is its setting [Illustr. 22, Note 18].

What then made the biologically accurate landscapes of Shishkin and many Russian landscapists of his generation 'national'? The regional floras and faunas that are characteristic of northern Russia, including the forest floras, are neither unique nor confined to Russia, nor even restricted to the Palaearctic bioregion in general. Climax species are by definition widespread, and whole ecosystems can be closely similar in appropriate climates and geological conditions at similar latitudes across the world. A least in Europe, national identity is therefore seldom invested in particular species (though the Edelweiss in Switzerland and the Tyrol may immediately spring to mind, or the reindeer in Lapland and the extreme north of Siberia), and it is just as seldom invested in a particular mix of dominant species. Where plants are concerned, there are indeed rare endemics found only in restricted areas of Russia, including the areas in which Shishkin and others worked, but these are most often distinguishable from more common species only on close examination by a specialist, and they are not the plants that appear in the landscapes of Shishkin and his compatriots: it is the widespread climax species that feature in their paintings. Where animals are concerned, Ursus arctos arctos, the Eurasian Brown Bear, has more of a claim to be an emblem of the specifically Russian forest environment, as evidenced by the pervasive popularity throughout the twentieth century of Shishkin's Morning in a Pine Forest (1889) [Illustr. 46], which could be encountered from the cover of a third-grade school reader from 1960 [Illustr. 47, Note 16] to the pages of the satirical humor magazine Krokodil in the 1980s [Illustr. 48]. Even so, bears in a forest setting are not exclusively emblematic of Russia: they are to be found today throughout the relevant European ecological regions (formally, the Scandinavian and Russian Taiga and the Sarmatic Mixed Forests), including Eastern Europe and Northern Scandinavia, with isolated populations in the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Balkans and Greece. Meanwhile, the equivalent ecological region in the Nearctic has two closely related subspecies, U. a. middendorffi and U. a. horribilis, and an abundant population of the similar Ursus americanus, the American Black Bear, which despite its common name is as likely to be brown as black. Canada and the United States have bestowed on the bear at least as large a place in their popular visual culture as have the Russians, and given the strong similarity in the climax vegetation of the Russian and North American bear habitats, it would in fact be difficult to attribute an uncaptioned painting of bears in a boreal forest to the appropriate continent, unless the artist had included at least one plant, bird or animal that occurs on one continent but not the other, and portrayed it accurately enough to allow certain identification. In the case of plants, the indicator species would probably not be trees, colourful flowering plants or fungi, but obscure and less conventionally aesthetic components of the forest undergrowth, which a landscape artist would be tempted to treat impressionistically as background rather than depict in identifiable detail. As an example, in the densely forested foothills of the Cascade Mountains in Washington State, USA [Illustr. 49: bear habitat in Western North America], there is an abundant population of bears, and scenes like Shishkin's Morning in a Pine Forest are relatively commonplace. What betrays the location of this habitat is the prominent component of the forest understory in the foreground of Illustr. 49, Oplopanax horridus (Devil's Club), which does not occur in Eurasia [Illustr. 50, Note 17: Oplopanax horridus at close quarters]. There is a similar indicator in the background of Illustr. 22: not the fungus, which even when photographed at a range of a few feet cannot be unambigously distinguished from Lepiota species occurring in Russia, but the Western Sword Fern (Polystichum munitum) that is its setting [Illustr. 22, Note 18].

What became a national characteristic of Russian landscape paintings in the second half of the nineteenth century, then, was not so much the depiction of particular species or groups of species, since even those that came to be regarded in Russia as emblematic of the nation were no less so in the landscapes of other cultures in ecologically similar regions. Rather, what made the paintings in question distinctive was their high degree of attention to bio-geographic detail, which owed something to two components of the culture of natural history: botanical illustration and nature photography. From the biological point of view, there was little in the intensely focused landscapes of Shishkin and many of his contemporaries that was peculiarly Russian, but they showed an unusual willingness to let unpeopled landscapes, and fragments of landscapes, speak for themselves, on the assumption that the soul of their nation was invested in the microcosms of its forests, steppes, and rivers, or even just in a good stand of weeds. In his Morning on the Dniepr Kuindzhi took the trouble to make two butterflies identifiable, but both of them occur commonly throughout Eurasia, and one has an extensive range in North America while the other has been recorded there; what is more distinctively Russian about this painting is that a clump of the most ordinary wildflowers, complete with the butterflies that frequent them, is made to dominate an extensive view of one of this vast country's most famous rivers.

The quest of many late nineteenth-century Russian landscapists for the natural biological structure of a scene tended to endow the microcosmic landscape with the monumental scale of the macrocosmic. The key to the composition of the intensive Russian landscapes of Shishkin and many of his contemporaries is the tension between the two universes of nature, the 'macro' and the 'micro': between the vast worlds of the impenetrable forest or the sky above, and the receding levels of detail of a few living organisms viewed in their intimate details, if necessary through a lens. It is this second universe that was so assiduously explored by naturalists in late nineteenth century Europe and America with the help of sketchbook and camera, and both their methods and their scientific vision of the world affected those who painted nature. In the tradition of most of the world's landscape painting in any age, landscape images have a cosmological function, and suggest an ordering of the visible universe. Shishkin in particular was no exception, but the microcosmic order he tried to capture and convey does not reflect the traditional principles of landscape composition, Russian or European, and is not fully understood by most viewers of his paintings, in his own time or ours.

* * * * * * *