|

For the first time, science became a central piece of public discourse. Until then, much of what is now considered scientific inquiry was pursued by a relatively small group of academics whose writings did not enjoy widespread circulation. Beginning in the late 17th century, there was a twofold development in academia that would bring about a rapid democratization of scientific knowledge. The first was the foundation of the Paris Academy and the Royal Society of London, two institutions whose primary purpose was to do scientific research and report their conclusions to the public.

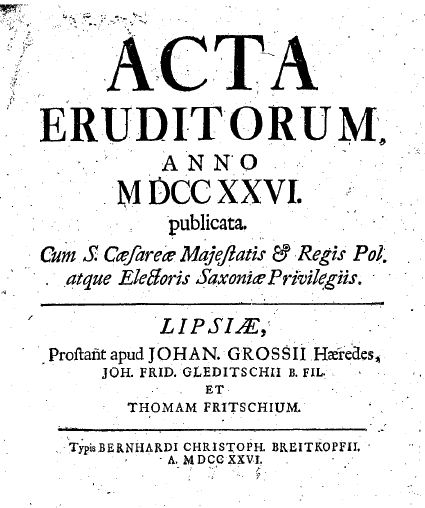

Leonhard Euler's life and work placed him at the center of European scholarship during this time of intellectual growth. Originally from Switzerland, he spent the majority of his career St. Petersburg and Berlin, while maintaining a robust correspondence with scholars across the continent. As part of the European Enlightenment, he was recognized as an exceptional scholar with a wide range of interest across mathematics and the sciences. In addition to the quality of his work, he produced an astonishing quantity of work: historian of science Clifford Truesdell calculated that of all the mathematical and scientific work published during the whole of the 18th century, a full 25% was written by Euler. Euler's prolificacy was aided by a second major development in academic life in the 18th century: the rise of scientific journals. These publications were often produced by the academies themselves (e.g., the Royal Society of London's Philosophical Transactions and the Paris Academy's Mémoires), though a fair number were produced independently (e.g., the Acta Eruditorum and Crelle's Journal). These new journals circulated to a wide audience that included many outside the scientific community. In one sense, these are among the first "popular science" magazines, in that scientific results were reported to an audience of non-specialists. As such, the 18th century was a time when scientific tracts could become bestsellers. One of Euler's books, Lettres à une princesse d'Allemagne (Letters to a German Princess), went through thirty-eight printings in nine different languages, and remained in print for a century.

Resources and Information on Euler's Life and Work:

|