ANESTHESIA FOR MAXILLOFACIAL TRAUMA

JOHN BRAMHALL PhD MD

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON, SEATTLE.

ASSESSING THE PATIENT

Evaluate the usual ABCs, get reports from initial care providers

then exercise your own judgement about the state of the patient.

Is the victim awake, alert and cooperative or unconscious/obtunded?

Extensive injuries requiring immediate resuscitation and corrective

surgery or isolated facial injury for elective repair? Possibility

of C-spine injury or closed head injury (mechanism of trauma)?

Is the victim scheduled for surgery? What procedures? Is general

anesthesia required? If regional techniques are planned, is airway

security an issue? Don’t have your actions dictated by generalists

less experienced than you in airway management.

Personally emphasize the need for early airway control and neurologic assessment of the head injured trauma patient, because the rapid development of facial edema obscures the pupils and obstructs the upper airway - the eyes and lips are the "shock organs" of the face and develop edema rapidly after blunt facial trauma. Evaluate the pupils, look for lateralizing neurologic abnormalities and accurately assess the level of consciousness of the patient while securing the airway of the trauma patient with facial injuries. Changes in the level of consciousness, pupil size, and development of clinical signs of intracranial hypertension, i.e., hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular breathing patterns, must be documented; "assume the worst until proven otherwise."

Ask yourself, is the victim cyanotic, apneic, dyspneic, dysphoric, agitated? Are accessory muscle being recruited? Is the victim leaning forward, drooling blood, gagging, wheezing, gasping, choking? Is the victim supine and likely to aspirate blood or vomitus at any moment? Can the mouth be opened, the neck extended, the tongue and uvula visualized? Are there lacerations to the larynx, dislodged teeth, clots of blood in the mouth? Is direct laryngoscopy feasible or do you anticipate need for fiberoptic? Are there relative contraindications to an awake intubation (victim already asleep, intoxicated, irrational, psychotic?). Do you have to act immediately?

EVALUATE THE INJURIES - SOFT TISSUE vs. BONE

FRACTURES:

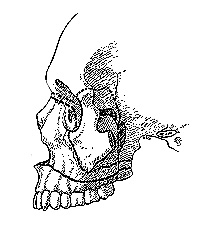

Significant bone trauma can co-exist with only modest soft tissue

injury; similarly, dramatic soft tissue injury may occur in the

absence of facial fractures. Mandible fractures will typically

involve the ramus; a bilateral fracture

may mobilize a bone segment and result in impaction of the upper

airway. The force of impact may be transmitted to the condyle

or directly to the TMJ, making the mouth difficult to open. Zygomatic

arch fractures may similarly affect jaw opening thus complicating

tracheal intubation. Chemical, electrical or flame burns can cause

extensive tissue damage to the face and also to the airway; edema

and tissue sloughing can result in difficult spontaneous breathing

and can also greatly complicate airway management. Facial fractures

were classified by LeFort:

ONE: Maxilla;

TWO: Midface; THREE: Separation of midface structures from cranial

skeleton (which may lead to shear injury of the base of the brain,

and will generally represent an absolute contraindication for

nasal intubation, naso-gastric tube placement or even for aggressive

mask ventilation until evaluation by radiology or MFS service).

ONE: Maxilla;

TWO: Midface; THREE: Separation of midface structures from cranial

skeleton (which may lead to shear injury of the base of the brain,

and will generally represent an absolute contraindication for

nasal intubation, naso-gastric tube placement or even for aggressive

mask ventilation until evaluation by radiology or MFS service).

EVALUATE THE INJURIES - BLUNT vs. PENETRATING

TRAUMA

Blunt trauma is commonly seen in cases of assault, falls, traffic

accidents and work-place injury. The classic penetrating injury

of the face is the gun-shot wound, but also often results from

motor vehicle accidents. Penetrating injuries will frequently

involve bleeding, loss of skeletal support, fragmentation of teeth

and bone, and extensive tissue swelling; ability to ventilate

may be seriously affected and normal anatomical landmarks may

be obliterated, making airway assessment and definition very problematic.

Blunt trauma may appear to involve less facial rearrangement but

airway definition may be even more difficult in cases of severe

mid-face trauma.

Blunt trauma causing extensive facial injury should alert you to the possibility of concomitant cervical spine injury and closed head injury. There may be spinal fractures or dislocations; there may be cerebral contusions or intracranial hemorrhage; it is difficult to assess sensory and motor deficits in unconscious patients. Until the spine is cleared formally exercise appropriate caution and avoid all manipulation of the neck; consider the necessity for head CT or placement of intracranial pressure monitors prior to surgery under anesthesia.

ESTABLISH A PLAN OF ACTION

Do you need to define the airway now, if so how are you going

to proceed? What resources will you need? What difficulties can

you anticipate? Is there a risk that you can make things worse?

If the airway is patent and the patient is ventilated effectively,

then you can move on to establish a plan for surgical anesthesia;

most maxillofacial surgery will necessitate tracheal intubation.

MANAGE THE AIRWAY

Conscious patients are usually able to control their own airway;

make a very careful analysis of the situation before inducing

unconsciousness. If the upper airway is closed or obliterated

and you feel that intubation is likely to be difficult and time-consuming

you probably have to move immediately to a surgical airway. Even

cricothyrotomy or laryngeal jet ventilation can be very difficult

with a struggling patient. Don’t attempt emergent tracheostomy

unless you are highly skilled in the maneuver. It may be possible

to open the airway simply by applying a jaw thrust, or applying

traction to the mandible but unless this attempt is immediately

successful proceed to surgical airway.

If the circumstances are not so dire then establish a rational plan for securing the airway trans-orally. Consider the feasibility of direct laryngoscopy, the use of the LMA, the need for fiberoptic devices and associated airway anesthesia. Call for skilled assistance, make sure you have adequate equipment (suction, oxygen, ventilation device etc.) and make sure plan "B" and plan "C" are clearly defined and ready for immediate execution if needed. Emergencies are not good opportunities for trying out novel techniques, stick to what you know. If the airway is lost, all other resuscitative interventions are futile.

Mask ventilation has only limited use in facial trauma; there are constant problems attaining appropriate seal and adequate airway opening without applying pressure to fracture sites or extending the cervical spine. Always the risk of forcing blood or bile into the lungs, air into the stomach (or even into the subdural space). Far better to define and protect the airway definitively. All the usual techniques are open to you they are listed below, in the order in which they are most frequently considered. Follow the ASA algorithm for airway definition - it’s there to help you and will stop you from inadvertently burning bridges!

DIRECT LARYNGOSCOPY

Can be impossible, or unwise in

certain circumstances, but generally offers the most rapid route

to the establishment of a secure, protected airway. Consider this

approach first, then think of relative or absolute contraindications

before proceeding. DL invariably involves muscle relaxation (induced

or intrinsic), hypnotic induction and re-alignment of the airway;

these can all be profoundly dangerous in cases of extensive maxillofacial

trauma. Again, burn no bridges and plan your escape routes in

the event of trouble.

FLEXIBLE FIBEROPTIC BRONCHOSCOPE [FFB]

The FFB is probably the most useful instrument

in skillful hands. Allows awake intubation with minimal distress

in the appropriately reassured and medicated patient. Copious

blood, bile or oral secretions can make life difficult, as can

extensive pharyngeal edema or tissue rearrangement. Even if there

is a partially occluded airway, the fiberoptic can frequently

be advanced into the trachea if the patient is spontaneously breathing,

and thereby "blowing bubbles", identifying the route

from the trachea. Consider simultaneous mask

ventilation during fiberoptic evaluation of the oropharynx; and

note that venturi oxygenation (and a degree of CO2

clearance can be attained by intermittent insufflation via

the aspiration channel. Success with the technique is often dependent

on the quality of airway topical anesthesia.

LMA & Fastrach

The LMA can be very useful in stenting the upper airway, but in

itself does not protect the airway and does not permit positive

pressure ventilation when pulmonary or thoracic compliance is

limited. The "fastrach" LMA

facilitates formal tracheal intubation and may well come to account

for success in many emergent airway manipulations.

BULLARD/WU LARYNGOSCOPE

Useful when mouth opening and/or neck extension is limited. Essentially

curved laryngoscope blades that contain a fiberoptic bundle facilitating

a view of the oropharynx from the blade tip. A disadvantage is

that the blade forces the pharynx to adopt the geometry of the

blade.

RETROGRADE WIRE

Blind technique so there is a risk to using this approach in traumatized

airways and in cases of extensive midface fracture; however use

of retrograde wire placement can be life saving when ongoing hemorrhage

makes direct visualization of airway structures impossible.

LIGHT WAND

Another blind technique, not nearly as useful as the wire.

PERCUTANEOUS (TRANS-TRACHEAL) JET VETILATION

Consider this route if the airway is completely obstructed and

other approaches have failed or seem doomed a priori. Puncture the cricothyroid membrane with a 14

gauge catheter (or central line introducer), secure the catheter

confidently; connect a source of moderate-pressure oxygen (50

psi) and institute jet ventilation by intermittently injecting

oxygen for 1 second and allowing passive exhalation for 2-3 seconds.

The airway is not protected, the oxygenation source is tenuous

and complications such as barotrauma and subcutaneous emphysema

are common, so this is a technique for urgent, temporary oxygenation/ventilation,

not a definitive airway.

CRICO-THYROIDOTOMY

Emergent lifesaver! Palpate thyroid notch and prominence of cricoid

below it, cricothyroid membrane is the depression above the cricoid

cartilage. Make a vertical skin incision, push into membrane

(scissors, hemostat, etc.) and spread open airway. Endotracheal

or tracheostomy tube may be placed.

Once patient is stabilized, cricothyrotomy is revised to formal

tracheostomy in the operating room to

avoid the development of subglottic stenosis. Tracheostomy is

an elective procedure and requires skill, sterility and surgical

equipment.

ANESTHETIC

Choice of anesthetic technique is quite open, but bear in mind

that many facial reconstructions are long cases, have intermittent

intervals of intense stimulation and may involve significant blood

loss; play close attention to fluid management. Surgeons will

demand unencumbered access to the face and neck, may request controlled

hypotension at times and may also require intraoperative assessment

of nerve integrity. Secure the tube appropriately.

There are a number of variables to be considered (awake or asleep, sitting or supine, iv or inhalation technique, rapid sequence induction or controlled hypnosis, cricoid pressure needed?). Whether urgent or elective, it will be the rare maxillofacial case that does not require tracheal intubation.

Induction should always be smooth and controlled; hypertension may be harmful if it provokes recurrent or increased bleeding; hypotension will be harmful if cerebral perfusion is compromised in cases of closed head injury. Consider the possibility of globe injury when presented with orbital trauma; consider the possibility of losing a tenuous airway when paralytics are administered.

Maintenance can be based on volatile agent, intravenous agent or opioid; pay particular attention to fluid balance on long cases, particularly those involving reconstructive tissue flaps. The goal, as always, is a stable, immobile patient who is either insensate or compliant and cooperative. The goal for emergence is, again, for a smooth, gentle, rapid wake-up followed by safe, atraumatic extubation. There will be occasions when a deep extubation is appropriate, but these are quite infrequent in the context of maxillofacial trauma, particularly if the jaw is wired. If the patient is to remain intubated ensure adequate paralysis and/or sedation before leaving the operating suite.

One final comment: the practicing anesthesiologist will frequently encounter patients who were victims of facial trauma in the past. They may well have abnormal airway anatomy as a result of traumatic injury, surgical reconstruction and scar contractures (particularly in the case of burns). It is very wise to make a thorough survey of previous anesthetic records and a very complete evaluation of the patient before embarking on a course of airway manipulation that may involve some unanticipated, and tortuous, twists and turns - both physical and metaphoric.

PERTINENT REFERENCES

Bramhall, J & Cullen B.F. (1999)

Anesthesia for Trauma

(in) Current Surgical Therapy (ed., Trunkey)

Mosby, Philadelphia (in press)

http://www.trauma.org/anaesthesia/airway.html