3D Visual Output

In the last chapter, we discussed how interfaces communicate data, content, and animations on two-dimensional screens. However, human visual perception is not limited to two dimensions: we spend most of our lives interacting in three-dimensional space. The prevalence of flat screens on our computers, smartwatches, and smartphones is primarily due to limitations in the technology. However, with advances in 3D graphics, display technology, and sensors, we’ve been able to build virtual and augmented reality systems that allow us to interact with technology in immersive 3D environments.

Computing has brought opportunities to create dynamic virtual worlds, but with this has come the need to properly map those virtual worlds onto our ability to perceive our environment. This poses a number of interdisciplinary research challenges that has seen renewed interest over the last decade. In this chapter, we’ll explore some of the current research trends and challenges in building virtual reality and augmented reality systems.

Virtual reality

The goal of virtual realityvirtual reality: Interfaces that attempt to achieve immersion and presence through audio, vidoe, and tactile illusion. (VR) has always been the same as the 2D virtual realities we discussed in the previous chapter: immersionimmersion: The illusory experience of interacting with virtual content for what represents, as opposed to the low-level light, sound, haptics and other sensory information from whic it is composed. . Graphical user interfaces, for example, can result in a degree of immersive flow when well designed. Movies, when viewed in movie theaters, are already quite good at achieving immersion. Virtual reality aims for total immersion, while integrating interactivity.

But VR aims for more than immersion. It also seeks to create a sense of presencepresence: The sense of being physically located in a place and space. . Presence is an inherent quality of being in the physical world. And since we cannot escape the physical world, there is nothing about strapping on a VR headset that inherently lends itself to presence: by default, our exerience will be standing in a physical space with our head covered by a computer. And so a chief goal of VR is creating such a strong illusion that users perceive the visual sensations of being in a virtual environment, actually engaged and psychologically present in the environment.

One of the core concepts behind achieving presence in VR is enabling the perception of 3D graphics by presenting a different image to each eye using stereo displays. By manipulating subtle differences between the image in each eye, it is possible to make objects appear at a particular depth. An early example using this technique was the View-Master , a popular toy developed in the 1930s that showed a static 3D scene using transparencies on a wheel.

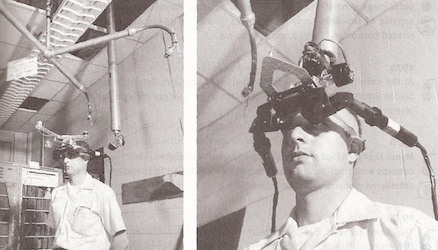

One of the first virtual reality systems to be connected to a computer was Ivan Sutherland’s “Sword of Damocles”, shown below, and created in 1968. With his student Bob Sproull, the headmounted display they created was far too heavy for someone to wear. The computer generated basic wireframe rooms and objects. This early work was pure proof of concept, trying to imagine a device that could render any interactive virtual world.

In the 1990s, researchers developed CAVE systems (cave automatic virtual environments) to explore fully immersive virtual reality. These systems used multiple projectors with polarized light and special 3D glasses to control the image seen by each eye. After careful calibration, a CAVE user will perceive a fully 3D environment with a wide field of view.

Jaron Lanier, one of the first people to write and speak about VR in its modern incarnation, originally viewed VR as an “empathy machine” capable of helping humanity have experiences that they could not have otherwise. In an interview with the Verge in 2017 , he lamented how much of this vision was lost in the modern efforts to engineer VR platforms:

If you were interviewing my 20-something self, I’d be all over the place with this very eloquent and guru-like pitch that VR was the ultimate empathy machine — that through VR we’d be able to experience a broader range of identities and it would help us see the world in a broader way and be less stuck in our own heads. That rhetoric has been quite present in recent VR culture, but there are no guarantees there. There was recently this kind of ridiculous fail where [ Mark ] Zuckerberg was showing devastation in Puerto Rico and saying, “This is a great empathy machine, isn’t it magical to experience this?” While he’s in this devastated place that the country’s abandoned. And there’s something just enraging about that. Empathy should sometimes be angry, if anger is the appropriate response.

While modern VR efforts have often been motivated by ideas of empathy, most of the research and development investment has focused on fundamental engineering and design challenges over content:

- Making hardware light enough to fit comfortably on someone’s head

- Untethering a user from cables, allowing freedom of movement

- Sensing movement at a fidelity to mirror movement in virtual space

- Ensuring users don’t hurt themselves in the physical world because of total immersion

- Devising new forms of input that work when a user cannot even see their hands

- Improving display technology to reduce simulator sickness

- Adding haptic feedback to further improve as sense of immersion

Most HCI research on these problems has focused on new forms of input and output. For example, researchers have considered ways of using the backside of a VR headset as touch input 10,12,18,25 10 Jan Gugenheimer, David Dobbelstein, Christian Winkler, Gabriel Haas, Enrico Rukzio (2016). Facetouch: Enabling touch interaction in display fixed uis for mobile virtual reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Yi-Ta Hsieh, Antti Jylhä, Valeria Orso, Luciano Gamberini, Giulio Jacucci (2016). Designing a willing-to-use-in-public hand gestural interaction technique for smart glasses. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

Franklin A. Lyons (2016). Mobile Head Mounted Display. U.S. Patent USD751072S1.

Eric Whitmire, Mohit Jain, Divye Jain, Greg Nelson, Ravi Karkar, Shwetak Patel, Mayank Goel (2017). Digitouch: Reconfigurable thumb-to-finger input and text entry on head-mounted displays. ACM Interactive Mobile Wearable Ubiquitous Technology.

Rahul Arora, Rubaiat Habib Kazi, Fraser Anderson, Tovi Grossman, Karan Singh, George Fitzmaurice (2017). Experimental Evaluation of Sketching on Surfaces in VR. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

Jan Gugenheimer, Dennis Wolf, Eythor R. Eiriksson, Pattie Maes, Enrico Rukzio (2016). GyroVR: simulating inertia in virtual reality using head worn flywheels. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Benjamin Long, Sue Ann Seah, Tom Carter, Sriram Subramanian (2014). Rendering volumetric haptic shapes in mid-air using ultrasound. ACM Transactions on Graphics.

Samuel B. Schorr and Allison M. Okamura (2017). Fingertip Tactile Devices for Virtual Object Manipulation and Exploration. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

Alexa F. Siu, Mike Sinclair, Robert Kovacs, Eyal Ofek, Christian Holz, and Edward Cutrell (2020). Virtual Reality Without Vision: A Haptic and Auditory White Cane to Navigate Complex Virtual Worlds. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

Andre Zenner and Antonio Kruger (2017). Shifty: A weight-shifting dynamic passive haptic proxy to enhance object perception in virtual reality. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics.

Inrak Choi, Heather Culbertson, Mark R. Miller, Alex Olwal, Sean Follmer (2017). Grabity: A wearable haptic interface for simulating weight and grasping in virtual reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Hrvoje Benko, Christian Holz, Mike Sinclair, Eyal Ofek (2016). NormalTouch and TextureTouch: High-fidelity 3D Haptic Shape Rendering on Handheld Virtual Reality Controllers. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Some approaches to VR content have focused on somewhat creepy ways of exploiting immersion to steer users’ attention or physical direction of motion. Examples include using a haptic reflex on the head to steer users 15 15 Yuki Kon, Takuto Nakamura, Hiroyuki Kajimoto (2017). HangerOVER: HMD-embedded haptics display with hanger reflex. ACM SIGGRAPH Emerging Technologies.

Akira Ishii, Ippei Suzuki, Shinji Sakamoto, Keita Kanai, Kazuki Takazawa, Hiraku Doi, Yoichi Ochiai (2016). Optical marionette: Graphical manipulation of human's walking direction. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Other more mainstream applications have included training simulations and games 27 27 Zyda, M. (2005). From visual simulation to virtual reality to games. Computer, 38(9), 25-32.

Pan, Z., Cheok, A. D., Yang, H., Zhu, J., & Shi, J. (2006). Virtual reality and mixed reality for virtual learning environments. Computers & Graphics.

Jarrod Knibbe, Jonas Schjerlund, Mathias Petraeus, and Kasper Hornbæk (2018). The Dream is Collapsing: The Experience of Exiting VR. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

Augmented reality

Augmented realityaugumented reality: An interface that layers on interactive virtual content into the physical world. (AR), in contrast to virtual reality, does not aim for complete immersion in a virtual environment, but to alter reality to support human augmentation. aa Augmented reality and mixed reality are sometimes used interchangeably, both indicating approaches that superimpose information onto our view of the physical world. However, marketing has often defined mixed reality as augmented reality plus interaction with virtual components. The vision for AR goes back to Ivan Sutherland (of Sketchpad ) in the 1960’s, who dabbled with head mounted displays for augmentation. Only in the late 1990’s did the hardware and software sufficient for augmented reality begin to emerge, leading to research innovation in displays, projection, sensors, tracking, and, of course, interaction design 2 2 Azuma, R., Baillot, Y., Behringer, R., Feiner, S., Julier, S., & MacIntyre, B (2001). Recent advances in augmented reality. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications.

Technical and design challenges in AR are similar to those in VR, but with a set of additional challenges and constraints. For one, the requirements of tracking accuracy and latency are much stricter, since any errors in rendering virtual content will be made more obvious by the physical background. For head-mounted AR systems, the design of displays and optics are challenging, since they must be able to render content without obscuring the user’s view of the real world. When placing virtual objects in a physical space, researchers have looked at how to match the lighting of the physical space so virtual objects look believable 16,22 16 P. Lensing and W. Broll (2012). Instant indirect illumination for dynamic mixed reality scenes. IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR).

T. Richter-Trummer, D. Kalkofen, J. Park and D. Schmalstieg, (2016). Instant Mixed Reality Lighting from Casual Scanning. IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR).

Sergio Orts-Escolano, Christoph Rhemann, Sean Fanello, Wayne Chang, Adarsh Kowdle, Yury Degtyarev, David Kim, Philip L. Davidson, Sameh Khamis, Mingsong Dou, Vladimir Tankovich, Charles Loop, Qin Cai, Philip A. Chou, Sarah Mennicken, Julien Valentin, Vivek Pradeep, Shenlong Wang, Sing Bing Kang, Pushmeet Kohli, Yuliya Lutchyn, Cem Keskin, Shahram Izadi (2016). Holoportation: virtual 3d teleportation in real-time. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Interaction issues here abound. How can users interact with the same object? What happens if the source and target environments are not the same physical dimensions? What kind of broader context is necessary to support collaboration? Some research has tried to address some of these lower-level questions. For example, one way for remote participants to interact with a shared object is to make one of them virtual, tracking the real one in 3D 19 19 Ohan Oda, Carmine Elvezio, Mengu Sukan, Steven Feiner, Barbara Tversky (2015). Virtual replicas for remote assistance in virtual and augmented reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Blaine Bell, Tobias Höllerer, Steven Feiner (2002). An annotated situation-awareness aid for augmented reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Blaine Bell, Steven Feiner, Tobias Höllerer (2001). View management for virtual and augmented reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Cimen, G., Yuan, Y., Sumner, R. W., Coros, S., & Guay, M. (2017). Interacting with intelligent Characters in AR. Workshop on Artificial Intelligence Meets Virtual and Augmented Worlds (AIVRAR).

Some interaction research attempts to solve lower-level challenges. For example, many AR glasses have narrow field of view, limiting immersion, but adding further ambient projections can widen the viewing angle 5 5 Hrvoje Benko, Eyal Ofek, Feng Zheng, Andrew D. Wilson (2015). FoveAR: Combining an Optically See-Through Near-Eye Display with Projector-Based Spatial Augmented Reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

Enylton Machado Coelho, Blair MacIntyre, Simon J. Julier (2005). Supporting interaction in augmented reality in the presence of uncertain spatial knowledge. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

From smartphone-based VR, to the more advanced augmented and mixed reality visions blending the physical and virtual worlds, designing interactive experiences around 3D output offers great potential for new media, but also great challenges in finding meaningful applications and seamless interactions. Researchers are still hard at work trying to address these challenges, while industry forges ahead on scaling the robust engineering of practical hardware.

There are also many open questions about how 3D output will interact with the world around it:

- How can people seamlessly switch between AR, VR, and other modes of use while performing the same task?

- How can VR engage groups when not everyone has a headset?

- What activities are VR and AR suitable for? What tasks are they terrible for?

These and a myriad of other questions are critical for determining what society chooses to do with AR and VR and how ubiquitous it becomes.

References

-

Rahul Arora, Rubaiat Habib Kazi, Fraser Anderson, Tovi Grossman, Karan Singh, George Fitzmaurice (2017). Experimental Evaluation of Sketching on Surfaces in VR. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

-

Azuma, R., Baillot, Y., Behringer, R., Feiner, S., Julier, S., & MacIntyre, B (2001). Recent advances in augmented reality. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications.

-

Blaine Bell, Steven Feiner, Tobias Höllerer (2001). View management for virtual and augmented reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Blaine Bell, Tobias Höllerer, Steven Feiner (2002). An annotated situation-awareness aid for augmented reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Hrvoje Benko, Eyal Ofek, Feng Zheng, Andrew D. Wilson (2015). FoveAR: Combining an Optically See-Through Near-Eye Display with Projector-Based Spatial Augmented Reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Hrvoje Benko, Christian Holz, Mike Sinclair, Eyal Ofek (2016). NormalTouch and TextureTouch: High-fidelity 3D Haptic Shape Rendering on Handheld Virtual Reality Controllers. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Inrak Choi, Heather Culbertson, Mark R. Miller, Alex Olwal, Sean Follmer (2017). Grabity: A wearable haptic interface for simulating weight and grasping in virtual reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Cimen, G., Yuan, Y., Sumner, R. W., Coros, S., & Guay, M. (2017). Interacting with intelligent Characters in AR. Workshop on Artificial Intelligence Meets Virtual and Augmented Worlds (AIVRAR).

-

Enylton Machado Coelho, Blair MacIntyre, Simon J. Julier (2005). Supporting interaction in augmented reality in the presence of uncertain spatial knowledge. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Jan Gugenheimer, David Dobbelstein, Christian Winkler, Gabriel Haas, Enrico Rukzio (2016). Facetouch: Enabling touch interaction in display fixed uis for mobile virtual reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Jan Gugenheimer, Dennis Wolf, Eythor R. Eiriksson, Pattie Maes, Enrico Rukzio (2016). GyroVR: simulating inertia in virtual reality using head worn flywheels. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Yi-Ta Hsieh, Antti Jylhä, Valeria Orso, Luciano Gamberini, Giulio Jacucci (2016). Designing a willing-to-use-in-public hand gestural interaction technique for smart glasses. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

-

Akira Ishii, Ippei Suzuki, Shinji Sakamoto, Keita Kanai, Kazuki Takazawa, Hiraku Doi, Yoichi Ochiai (2016). Optical marionette: Graphical manipulation of human's walking direction. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Jarrod Knibbe, Jonas Schjerlund, Mathias Petraeus, and Kasper Hornbæk (2018). The Dream is Collapsing: The Experience of Exiting VR. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

-

Yuki Kon, Takuto Nakamura, Hiroyuki Kajimoto (2017). HangerOVER: HMD-embedded haptics display with hanger reflex. ACM SIGGRAPH Emerging Technologies.

-

P. Lensing and W. Broll (2012). Instant indirect illumination for dynamic mixed reality scenes. IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR).

-

Benjamin Long, Sue Ann Seah, Tom Carter, Sriram Subramanian (2014). Rendering volumetric haptic shapes in mid-air using ultrasound. ACM Transactions on Graphics.

-

Franklin A. Lyons (2016). Mobile Head Mounted Display. U.S. Patent USD751072S1.

-

Ohan Oda, Carmine Elvezio, Mengu Sukan, Steven Feiner, Barbara Tversky (2015). Virtual replicas for remote assistance in virtual and augmented reality. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Sergio Orts-Escolano, Christoph Rhemann, Sean Fanello, Wayne Chang, Adarsh Kowdle, Yury Degtyarev, David Kim, Philip L. Davidson, Sameh Khamis, Mingsong Dou, Vladimir Tankovich, Charles Loop, Qin Cai, Philip A. Chou, Sarah Mennicken, Julien Valentin, Vivek Pradeep, Shenlong Wang, Sing Bing Kang, Pushmeet Kohli, Yuliya Lutchyn, Cem Keskin, Shahram Izadi (2016). Holoportation: virtual 3d teleportation in real-time. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST).

-

Pan, Z., Cheok, A. D., Yang, H., Zhu, J., & Shi, J. (2006). Virtual reality and mixed reality for virtual learning environments. Computers & Graphics.

-

T. Richter-Trummer, D. Kalkofen, J. Park and D. Schmalstieg, (2016). Instant Mixed Reality Lighting from Casual Scanning. IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR).

-

Samuel B. Schorr and Allison M. Okamura (2017). Fingertip Tactile Devices for Virtual Object Manipulation and Exploration. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

-

Alexa F. Siu, Mike Sinclair, Robert Kovacs, Eyal Ofek, Christian Holz, and Edward Cutrell (2020). Virtual Reality Without Vision: A Haptic and Auditory White Cane to Navigate Complex Virtual Worlds. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI).

-

Eric Whitmire, Mohit Jain, Divye Jain, Greg Nelson, Ravi Karkar, Shwetak Patel, Mayank Goel (2017). Digitouch: Reconfigurable thumb-to-finger input and text entry on head-mounted displays. ACM Interactive Mobile Wearable Ubiquitous Technology.

-

Andre Zenner and Antonio Kruger (2017). Shifty: A weight-shifting dynamic passive haptic proxy to enhance object perception in virtual reality. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics.

-

Zyda, M. (2005). From visual simulation to virtual reality to games. Computer, 38(9), 25-32.