How to prototype

You think you understand your design problem. You have an idea of how to solve it. Now you just have to build it, and problem solved, right?

Wrong. Here are several ideas why just building something is the wrong next step:

- Building things takes a long time and is very expensive, and usually much more than anyone thinks. Don’t spend 6 months engineering something that isn’t useful.

- Once you have built something, what if it doesn’t work? You’ll have done all of that building and have to throw it all away, or worse yet, you’ll try to make your solution work, even though it never will, because of the sunk cost fallacy 3 3

Lehey, R. L. (2014). Letting go of sunk costs. Psychology Today.

. - What if you build something and not only does it not solve the problem, but your understanding of the problem was all wrong? Then, not only do you have to throw away what you build, but you have to reframe the problem.

Designers avoid these problems by making and testing prototypes . At the beginning of a project, there are many uncertainties about how something will work, what it will look like, and whether it addresses the problem. Designers use prototypes to resolve these uncertainties, iterate on their design based on feedback, and converge toward a design that best addresses the problem.

This means that every prototype has a single reason for being: to help you make decisions. You don’t make a prototype in the hopes that you’ll turn it into the final implemented solution. You make it to acquire knowledge, and then discard it, using that knowledge to make another better prototype.

Because the purpose of a prototype is to acquire knowledge, before you make a prototype, you need to be very clear on what knowledge you want from the prototype and how you’re going to get it. That way, you can focus your prototype on specifying only the details that help you get that knowledge, leaving all of the other details to be figured out later. Let’s walk through an example. Imagine you’re working with a community of assisted living residents who want the ability to easily order a pizza without having to remember a phone number, make a phone call, or share an address. You have an idea for a smart watch application that lets you order delivery pizza with a single tap. You have some design questions about it. Each of these design questions demands a different prototype:

- Will residents accidentally order pizza? How would you find out without having to build the whole thing? Perhaps you wouldn’t build anything, and you’d just study the occurrence of accidental taps in smart watch platforms. Or perhaps you’d take an existing single-tap smart watch application and pretend it was your single tap pizza ordering application, seeing if you accidentally activate the app’s single app functionality.

- What feedback do residents need that their pizza is on the way? You could look at the feedback that the online ordering gives and design a UI that gives the same feedback. Or, you could simulate the feedback with text messages, setting up an experiment where you pretend to be the application and give the feedback the app would give via messages.

- Would residents feel safe ordering pizza from their watch? This is harder to build a prototype for, since to find out, you’d need to actually give people the capability. Perhaps you’d extend your existing pizza delivery smartphone app with the watch functionality (building it for the phone instead of the watch) and see if anyone uses it as part of a beta program. If you see high demand, you could get data on how many of those smartphone users have smart watches and then decide whether to take the risk of building the actual watch application.

As you can see, prototyping isn’t strictly about learning to make things, but also learning how to decide what prototype to make and what that prototype would teach you. These are judgements that are highly contextual because they depend on the time and resources you have and the tolerance for risk you have in whatever organization you’re in.

You don’t always have to prototype. If the cost of just implementing the solution is less than prototyping, perhaps it’s worth it to just create it. That cost depends on the skills you have, the tools you have access to, and what knowledge you need from the prototype.

Because the decision to prototype depends on your ability and your tools, good designers know many ways to prototype, reducing the cost of prototyping. A designers’ prototyping toolbox is extremely diverse, because it basically contains anything you might use to simulate the existence of your design. Let’s discuss a few genres of prototypes that are common in the software industry, ranging from low to high fidelity.

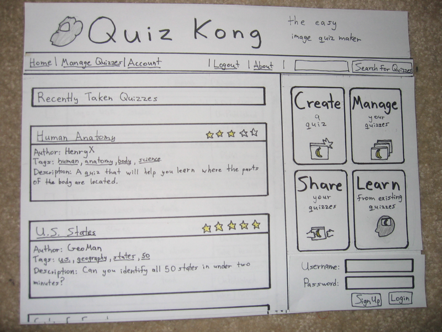

The fastest and easiest form of prototype is a sketch , which is a low-fidelity prototype that’s created by hand. See the drawing at the top of this page? That’s a sketch. Get good at using your hands to draw things that you want to create so that you can see them, communicate them, and evaluate them. With enough skill, people can sketch anything, and they almost always do it faster than in any other media. On the other hand, because they have the least detail of any prototype (making them low-fidelity), they’re most useful at the beginning of a design process.

Another useful prototyping method is bodystorming :

In this method, rather than using our hands, we use our whole bodies to simulate the behavior and interactions we want to explore. Like sketching, it’s incredibly fast, and doesn’t really require any special tools.

Sketching and bodystorming are the lowest-fidelity methods of prototyping, requiring very little to prepare. If you’re willing to get some paper, pens, and tape, you can also try creating paper prototypes

Whereas a sketch is just an informal drawing used to facilitate communication, a paper prototype is something you can actually test. Creating one involves creating a precise wireframe for every screen a person might encounter while using a design, including all of the feedback the user interface might provide while someone is using it. This allows you to have someone pretend to use a real interface, but clicking and tapping on paper instead of a screen. If you plan the layout of an interface in advance, then decide which parts of the interface you need to change in order to test the interface with someone, you can build one of these in less than an hour.

With even more time, you can use video and video editing to show interactions with an interface:

Another popular technique is called Wizard of Oz prototyping 1,2 1 Hoysniemi, J., Hamalainen, P., and Turkki, L. (2004). Wizard of Oz prototyping of computer vision based action games for children. Conference on Interaction Design and Children (IDC).

Hudson, S., Fogarty, J., Atkeson, C., Avrahami, D., Forlizzi, J., Kiesler, S., Lee, J. and Yang, J. (2003). Predicting human interruptibility with sensors: a Wizard of Oz feasibility study. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

A more recent example is late-night host James Corden prototyping gesture-based musical instruments for his Apple Watch (with the help of his band):

Beyond these low-fidelity methods are a wide range of higher fidelity prototyping tools, which support rapid prototyping of particular genre of designs, such as web and mobile applications. Tools like these, including Figma , InVision , Adobe XD , and Sketch , support collaboration, interactive wireframes, and workflows for importing and exporting to other media. The level of fidelity that these tools offer allow you to closely mimic a final product without having to build a final product, but they take much more time to use, because you have to make more decisions about more details.

Clearly, there are lot of different media you can use to answer a design question. Which one to use depends on the time/fidelity tradeoff that you’re willing to make 4 4 Sauer, J. and Sonderegger, A. (2009). The influence of prototype fidelity and aesthetics of design in usability tests: Effects on user behaviour, subjective evaluation and emotion. Applied Ergonomics.

Of course, after all of this discussion of making, it’s important to reiterate: the purpose of a prototype isn’t the making of it, but the knowledge gained from making and testing it. This means that what you make has to be closely tied to how you test it. What aspect of the prototype is most critical to the test, and therefore must be high fidelity?What details can low-fidelity, because they have less bearing on what you’re trying to learn?Who will you test it with, and are they in a position to give you meaningful feedback about the prototype’s ability to serve your stakeholders’ needs?As we will discuss in the coming chapters, these questions have their own complexity.

References

-

Hoysniemi, J., Hamalainen, P., and Turkki, L. (2004). Wizard of Oz prototyping of computer vision based action games for children. Conference on Interaction Design and Children (IDC).

-

Hudson, S., Fogarty, J., Atkeson, C., Avrahami, D., Forlizzi, J., Kiesler, S., Lee, J. and Yang, J. (2003). Predicting human interruptibility with sensors: a Wizard of Oz feasibility study. ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing (CHI).

-

Lehey, R. L. (2014). Letting go of sunk costs. Psychology Today.

-

Sauer, J. and Sonderegger, A. (2009). The influence of prototype fidelity and aesthetics of design in usability tests: Effects on user behaviour, subjective evaluation and emotion. Applied Ergonomics.