If you are not interested in my blog and just want to view the latest earthquake activity you can you can link to the daily histogram and hourly histogram of earthquake counts here. You may need to refresh your browser if you have looked at them before and you should read my footnote [1] to understand what is being shown.

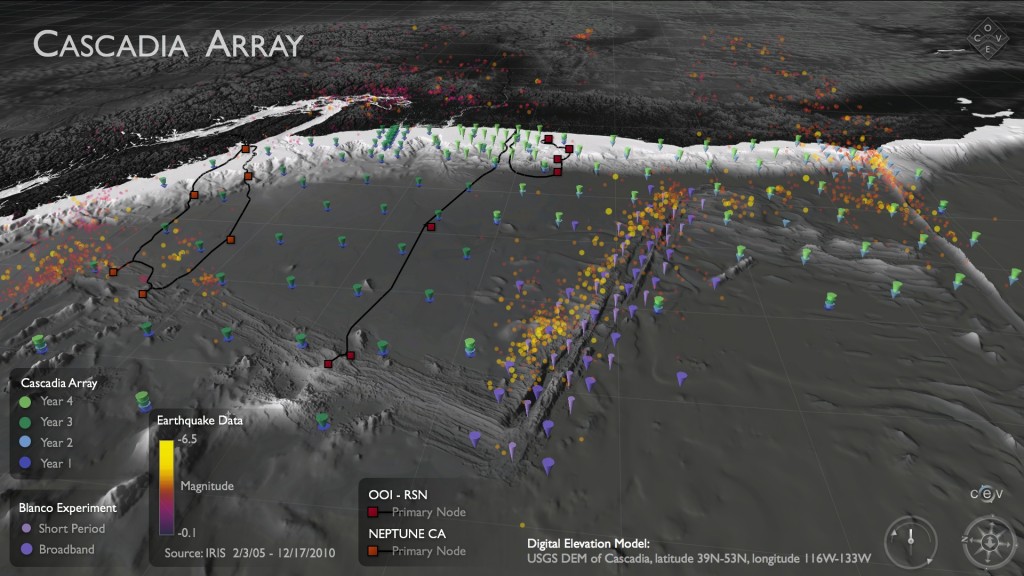

On December 15, the Consortium of Ocean Leadership announced the release of preliminary data from seismometers on the National Science Foundation’s Ocean Observatory Initiative (OOI) cabled observatory (announcement here ) through the Incorporate Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) Data Management Center (DMC). The cabled observatory was installed by the University of Washington (UW) in a marathon effort this past summer but this is the first data to be released for public consumption. It has been a decade since I was involved in the seismic monitoring component of a prototype observatory experiment on the Endeavour segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge, so the release real time data from Axial Seamount was quite exciting. I am even more excited now that I have had time to look at it; the data shows that the volcano is restless and lends support to the growing expectation that an eruption may occur fairly soon.

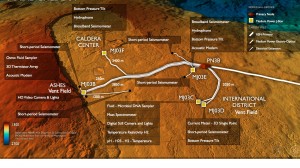

Configuration of the OOI cabled observatory on the summit of Axial Seamount (the figure was created for the OOI by the UW Center for Environmental Visualization and is available on the OOI website)

The cabled seismic network at Axial Seamount comprises 2 broadband and 5 short period seismometers in and around the summit caldera and another broadband 25 km to the southeast at the foot of the volcano. The seismometers record ground motions at a sample rate of 200 Hz but because of the US Navy’s concerns about the potential of the seismic network to record submarines, the initial live stream was limited to 8 Hz. Live streaming of the 200 Hz data commenced on January 7 and at present data has been backfilled to mid-November with several gaps of a few days; one is due to a network outage and others due to Navy testing. As operations continue, the 8 Hz stream will remain live, but at times the Navy will divert the 200 Hz data so that it can be screened for signals of interest before being either released or, hopefully not too often, embargoed. The 8 Hz data will be fine for many seismic applications but for my interest in monitoring the microearthquakes on the volcano, the 200 Hz data is important.

The OOI management has been cautious about releasing pre-commissioned data because they would prefer first to ensure its quality. However, in practice they do not have the staffing or expertise to evaluate all the data they are collecting so releasing it to the community is a pragmatic approach to quality control. Within a few days of the data coming on line, Anne Tréhu at Oregon State University took a quick look. She noted that overall the data is encouraging and of high quality, but also identifying some problems. The 200 Hz data streams included regular data gaps (13 minutes was missing every half an hour), a problem that is not present in live-streaming data and which has now been resolved for diverted data. More recently, Paul Bodin in the UW Department of Earth and Space Sciences has identified a timing problem with the two broadband seismometers at Axial summit. Their recordings of earthquakes are offset a few seconds from nearby short period seismometers. The cabled observatory engineers are presently working to rectify it (Note: the timing problem was successfully resolved as of January 23, 2015). These kind of teething problems are to be expected with any new seismic network; any network or field seismologists should feel very lucky if they have never had to wrestle with data gaps and timing problems! By releasing the data, the OOI has empowered seismologists who care about the program to get engaged and provide constructive input to improve the quality of its data.

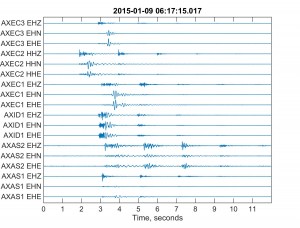

Example of a microearthquake recorded by the OOI cabled seismic network at Axial Seamount. On the EHZ (vertical) channels up to 4 water column reverberations of the P-wave are visible. On the EHN/EHE (horizontal) channels the S waves are characterized by higher amplitudes and lower frequencies.

In the past when I analyzed marine microearthquake data, my work started with the laborious and time consuming process of copying files of seismic data onto my computer, setting up and checking a relational database to organize the seismic time series and metadata, and installing complex software to access the data from my preferred analysis software (MATLAB®). However for this project I have discovered a really nifty piece of software created at the IRIS DMC called Iris Matlab Fetch (irisFetch.m) which uses java commands to directly bring chunks of data directly from the DMC into Matlab. It is not super fast and I can only grab a few hours of data at a time but it enabled me to start playing happily with the data within an hour of sitting down at my computer. Like Anne Tréhu and Paul Bodin one of the first things I noticed was the high quality of the waveforms.

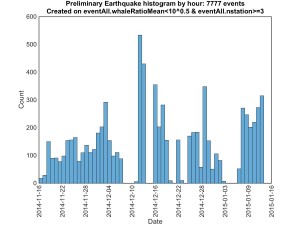

Daily histogram of earthquake count at Axial Seamount. Click on the image (and reload the resulting web page) to see an updating version of the histogram [1].

The OOI plans to release additional selected pre-commissioned data from the RSN with a tentative release date of January 30 (announcement here). It is going to be interesting to see the live streams of bottom pressure, tilt and hydrothermal time series to get a more complete picture of what the volcano is up to.

[1] Footnote: The daily and hourly histogram plots show preliminary estimate of the number of earthquakes detected by at least 3 seismometers. To detect events, the data is first filtered with a 4 Hz high pass filter and a trigger is registered every time the RMS amplitude in a moving 0.5-s-long window exceeds that of a 10-s-long window immediately before by a factor of 2. Events are identified when triggers are observed on at least 3 stations and 5 channels within a 1-s-long window. Events are classified as earthquakes (rather than fin whales) if on average the waveforms have more power in the 5-15 Hz band than the 15-30 Hz band in a 2-s-long window following the trigger. There are several long data gaps and quite a few smaller ones when no data is available and and other times when regular gaps that are offset in time between stations limit the number of recording stations at a given time and thus the ability to detect events.