Technology and the Quality of Teachers' Professional Work:

Redefining What It Means to Be an Effective Educator

Stephen T. Kerr

University of Washington

Paper prepared for the CCSSO Educational Technology Leadership Conference

January 13-14, 2000

REVISED DRAFT -- March 17, 2000

Address for correspondence:

Stephen T. Kerr

115 Miller Hall

University of Washington

Box 353600

Seattle, WA 98195

(206) 685-7562; (206) 543-8439 [fax]

stkerr@u.washington.edu

Technology and the Quality of Teachers' Professional Work:

Redefining What It Means to Be an Effective Educator

Stephen T. Kerr

University of Washington

Start with a scenario. Call it "Student Teaching, 2033":

We have taken a trip via time machine. It is 2033. We are watching a student in a teacher preparation program in a large Midwestern university preparing a portfolio of materials that will serve both as evidence of successful completion of the program and also as an important starting point for their future work as a practicing professional. All of the materials in the portfolio are electronic. There are several items that we recognize -- lesson plans, bits and pieces of student projects, evidence of student achievement gathered using varied assessment tools.

But there are other things here that are unfamiliar to our eyes -- descriptions of the student-teacher's work that incorporate video clips of classroom activities; there are numerous items that are themselves annotated with video, audio, and textual elements by the student-teacher, the cooperating teacher, the supervisor, students, and other student teachers from the same cohort. There are also reflections on the work of other teachers in the school that are similarly annotated by the student teacher, as well as by other educators in the school. There are documents that attest to the school's efforts over the academic semester when the student-teacher was present to address an especially problematic set of issues around the reading achievement of a group of newly arrived immigrant children from Macedonia; these incorporate a variety of animated graphic representations of the effectiveness of different sorts of instructional approaches and classroom grouping strategies. Finally, the portfolio includes video, audio, and textual interactions around tough instructional and assessment issues with a number of practicing teachers in the student-teacher's field from other schools across the district, region, and state.

We have the chance to ask the student-teacher one question, and after some thought, we say, "What difference do you think this technology will make to your work as a teacher?" There is a brief pause -- the question seems puzzling. Finally, the student teacher responds, "I don't think of it as 'technology' now -- it's just a part of what teachers do. I know from the courses I took on history of education that there was a time when teachers pretty much did their own thing, and they didn't have many opportunities to share how they worked with one another, but it all seems like ancient history. For me, being a teacher really means capturing the essence of my good professional practice with kids, and sharing that practice with my colleagues in ways that they can use and expand on. I was involved in using MuLTeaLs and ProXChG not just from the beginning of my work at the university, but also while I was still a student in high school -- we would annotate some of my teacher's materials for her. It's the only way that I can see to really work as a professional today. I kinda think of the old way as like how doctors must have worked before they had ways of telling each other what procedures and drugs worked and which ones didn't."

Today, the scenario may seem far-fetched. But while none of these technologies is sufficiently developed at present to be used by teachers in the sort of routine, day-to-day way described here, all exist in at least kernel form today. The possibilities outlined here suggest important changes for the future development of teaching, not only as an enterprise oriented toward furthering the intellectual development of students, but also as a professional activity involving intensive collaboration among peers. This paper proposes that technology must not only affect the ways in which instruction is done, but also penetrate the ways that teachers work together as professional colleagues. The perspectives outlined here are based on several co-mingling streams of research: (1) how we think of teachers' work as professional activity; (2) how teachers are prepared (through both pre- and in-service education) to collaborate professionally with each other in support of improved practice; (3) how technology can be used in aid of collaborative professional work (sometimes called CSCW, or Computer-Supported Collaborative Work). These research findings are outlined first. Next is presented a set of criteria for how we could judge the success or failure of efforts to use technology to support teachers' professional collaboration through such "virtual communities of practice," together with some relevant examples of how technology is contributing to such communities today. Finally, suggestions are offered for how states could both encourage and assess the abilities of teacher candidates to work professionally in these new ways.

Teachers' Work as Professional Activity

Are teachers truly "professionals"? The question is an old one; the answer clearly depends on what we mean by "professional." Sociologists who study work and occupations have described features that define a "profession" – a well-defined body of knowledge that new practitioners have to master; social consensus that only members of this occupational group will be allowed to address certain key matters of life and death, well-being, relationships with others, and so on; control from within the profession of standards that determine who is admitted and who not; codes of ethics and methods for handling renegade or deviant practitioners; and the ability and willingness to use political and social power in support of the profession's aims and members.

Whether teaching "qualifies" as a profession under such a definition is a matter of debate. Those who have examined education have suggested that perhaps it is best seen as a "semi-profession" (Etzioni, 1969); after all, control of standards for entry, advancement, and discipline does not lie wholly in the hands of teachers themselves, and the field does not have well-codified bodies of theory and practical techniques that predictably lead to replicable results. This latter point is one that bears careful attention for our purposes here.

For a professional to work as such, that individual must not only learn how to practice as a member of that field. They must also develop a concern, shared with other members of the profession, for moving practice forward, for contributing to the improvement of technique and for communicating those new perspectives to others. Physicians do this through articles written for medical journals about unexpected combinations of symptoms and how they sorted these out, about new surgical procedures, about unusual cases that did or did not respond to treatments in particular ways. They also learn about new developments in drugs from the representatives of pharmaceutical companies who visit their offices, about problems that have arisen in a particular hospital via in-house conferences to discuss what went wrong in specific cases, and about threats of new bouts of infectious illnesses that are circulated by relevant state and federal agencies. Others commonly recognized by sociologists as professionals – lawyers, architects, accountants, and so on – have similar (but not identical) mechanisms for describing, sharing, and commenting on changes in practice. There is, in other words, a culture of professional growth and development that emphasizes the individual's responsibility to share significant new information with peers, and to pay attention to such information circulated by others in the profession.

Teachers generally do not have such a culture of shared professional information exchange. While individual educators may and do take the initiative to publish descriptions of new techniques in professional journals and at to present them at conferences, many do not. While most school districts offer some form of in-service or continuing professional education to teachers, many participants in these efforts describe them as marginally effective at best – teachers assemble for an afternoon or a few hours on a weekend and are given "quick-fix" solutions to some problem, activities or approaches that can be directly and immediately implemented with little need for extra preparation or thought. The characterization of these as "sheep-dip solutions" is both colorful and, sadly, accurate.

One of the reasons that collegial interaction and development of professional norms for sharing information about practice have not developed more rapidly among teachers may be the dominance of traditional educational research studies as the principal way to discuss changes in education. But while professors in colleges of education and policymakers have learned how to read and use this sort of information, it remains foreign to most teachers. As Dede (2000, in this series) notes, "Teachers find direct knowledge of others' practices much more convincing than conventional forms of research evidence" (p. 10). Virtual learning communities, in other words, may provide a new avenue for teachers to exchange useful, specific information about changes in practice.

Preparing Teachers to Collaborate Professionally: The Role of Technology

A major problem with the current model of teacher preparation is that it does little to prepare future teachers to take on this responsibility of contributing to the growth of the profession through enhanced intra-professional communication. While teachers are often encouraged to "work as a professional team" and to participate in forms of information sharing, they often do not receive concrete examples of how to do this as part of their pre-service training. And, when they move into regular teaching positions, they typically find that the amount of time available to participate in any sort of professional development activity is woefully small. The issue of teachers' professional development has been seen as a serious one by many who have studied the present status of the teaching profession. For example, the National Commission on Teaching and America's Future made a series of recommendations on improving teachers' professional development, including making it a regular part of expectations for the teacher's day, and using learning networks more intensively (What Matters, 1996).

A number of studies have reviewed efforts to encourage teachers to engage in more intensive forms of professional sharing. Typically, such programs may involve some regular release time to participate in professional development groups, special weekend or other opportunities to work together at set intervals, or summer programs that bring teachers together for a workshop session during the summer. In some cases, these summer programs involve follow-up sessions held during the regular school year. For example, one comparative study of state-level teacher networks formed to offer these kinds of professional development opportunities suggested that:

they are more popular than conventional approaches to professional development, and they do offer many teachers deeper, more useful opportunities than are available from other sources. (Firestone & Pennell, 1997, p. 263)

Another recent review of efforts to promote teacher learning notes that:

Yet, almost to a study, the one consistent result is that helping teachers to learn to discuss and think and talk critically about their own practice can be painful and consumes considerable energy. Groups have to move beyond politeness and "that's fine for you" to … critical colleagueship. This involves developing norms, a language, trust, and a sense that change is desirable and expected, not merely possible. (Wilson & Berne, 1999; p. 200)

A few projects have attempted to bring technology to bear – especially videos of teachers' activity – as a catalyst to spur professional development. A study done for the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards (Frederiksen, Sipusik, Gamoran, and Wolfe, 1992; see also Gamoran, 1994) investigated the ways in which "video clubs" could provide a forum for teachers to present and talk about their work more deeply than was possible in traditional discussion groups. Among other things, viewing and commenting on video clips of teachers' lessons provided a fuller sense of the classroom context, the variety of students present, the types of interruptions or interaction problems that might distract students from the work, and the detailed nuances of teacher-student dialogue. But the opportunity went further than this. As the researchers concluded:

As it evolved, the computer has transformed many existing technologies and created entire new fields of human endeavor. We believe that Video Clubs have the same generative potential along the dimension of improving teaching practice. The dynamic that generates this potential is the construction by classroom teachers of a language of practice that is predicated on understanding the actual, imperfect working conditions inherent in a classroom. … The result is a multimedia library of teaching lore that will evolve over time, and which will include prototypical video segments of life in the classroom, along with a rich and evolving set of commentaries that contain the collective wisdom of the teaching profession. (p. 105)

This notion of the creation of a new "language of practice" is an important one to which we will return later. It is important to note, however, that the introduction of video into a classroom setting, especially where teachers and their activities are the subjects of the taping, is not something that teachers are likely to react to with equanimity. In a study that focused on enhancing dialogue among teachers around the creation of an interdisciplinary English-Social Studies curriculum, Wineburg & Grossman (1998) found that asking teachers to show and discuss videos of their own teaching was valuable, but also problematic:

No matter how safe the atmosphere, the act of putting a camera in a classroom raises the specter of evaluation. Moreover, the sheer novelty of watching oneself on tape can be unsettling. But we see videos as a key to overcoming the culture of privatism that pervades schools. Some teachers in our group had worked side-by-side for 20 years and had never seen one another teach until our first video club. (p. 352)

Many studies have pointed to the value of teachers' working collaboratively to support technology-based changes in instruction. The paper in this series by Thompson, Schmidt, and Stewart (2000, pp. 9-10) describes the range of activities engaged in by participants in the eCOMET project, including "after-school and summer workshops, … classroom modeling sessions, one-on-one mentoring programs, and small-group curriculum and technology project development sessions." The suggestion here is to make these kinds of transactions routine and expected, recordable, and shareable, via technology, with teachers across boundaries of space and time.

Teachers' interest in developing the ability to share results of their own work with colleagues through virtual communities of practice may need to grow in parallel with their awareness of the value of these approaches as learning experiences for their students. As Becker (2000, in this series) notes, "the relatively small minority of the computer-using teachers who selected having students 'communicate electronically with other people' (only 9% of all computer-using teachers) had, overall, the most constructivist philosophies. The next-most philosophically constructivist teachers were those who chose 'presenting information to an audience' and 'learning to work collaboratively' as their main objectives for student computer use" (p. 14).

While Becker's data did not explicitly address the issue of teachers' use of technologies to support intraprofessional communication and development, other findings from the same study indicate that teachers who are more familiar with and more frequent users of multiple types of software tend to be more constructivist in their teaching beliefs. We might assume that these same teachers, in the spirit of constructivist inquiry, would be more willing and more interested to share information about their own teaching with their peers. Other findings by Becker from a study of technology-using teachers in reform-oriented schools, show that 70% of teachers who use technology regularly with their students "reported they were now more willing 'to be taught by students' than three years previously" (p. 26), a quality that would support the sort of intensive exchange of pedagogical experience envisioned here.

Multimedia Languages for Teacher Learning (MuLTeaLs) in Action

We can think of the kind of system suggested in the opening scenario as a "Multimedia Language for Teacher Learning," (MuLTeaL for short). Its purpose is not simply to foster easier administrative manipulation of data by or for teachers. Rather, it is proposed here as a vehicle for a new kind of teacher activity – not just learning to become a member of a profession that one practices in the same ways until one retires, not simply absorbing new information on an occasional basis, but exchanging and commenting upon each others work with the aim of improving practice generally. This is a grand goal, and its complexity and challenge may doom it, but the potential rewards are also large. Let us consider for a moment what such a language might look like, what features it might have, what preparation teachers might have to use it, and how its use (to say nothing of its development) might be encouraged by relevant state and federal agencies.

Multimedia languages for communicating classroom practice. Such a language would need to provide a reliable way to capture and describe instruction – teachers' intentions, specific goals and instructional strategies, planned organization of classroom materials and activities, characterizations of (or readily accessible information about) learners, interactions among students as learning activities occur (including all the typical variation, incipient chaos, and unintended excursions that accompany learning in a classroom setting), and careful ways to record, accumulate, examine, and display varied results from the lesson. The language would also need to be easy to learn; teachers would need to find it relatively simple to figure out how to "speak" (record their own instructional activities), "read" (parse other teachers' recorded lessons), and "write" (participate in conversations with other professionals about the shape of lessons, the variables that make a difference, the problems of organization, ways of handling diverse student needs and learning styles in the classroom, and perhaps most importantly, the ways of assessing student learning and sharing resulting data with other teachers.) The language would need to provide useful information – in other words, it would need to give teachers something that they would find helpful, something that would lead them to use it, day by day. (Think of the numbers of people around the world who study English with a kind of desperation in the hope that someday that knowledge will enable them to live a better life.) And finally, the language would need to be not only utilitarian, but also enjoyable, pleasurable, interesting. It would need to lead the teacher into novel and surprising insights into the character of teaching in particular subjects, with particular students.

Grammar and syntax of the language: What grammatical and syntactical elements might a MuLTeaL actually have? While this is mostly conjectural, we can suggest several: (1) Video to capture the essence of instructional interaction, including use of multiple cameras to portray the entire scope of the classroom; (2) Multimedia to show at the same time students and teachers on split screens, student computer screens overlaid on that, capabilities to zoom in on particular activities, and so on; (3) Annotation of the above materials, by the teacher, via inserted text, audio commentary, animated overlays or other tools to isolate action, show and compare individuals, and so on; (4) Comment on others' work, by teachers other than the one who made the original recording, using all the methods and approaches described above, and also allowing for the insertion of materials illustrating their own practice; and (5) Comparative data analysis to permit examination of statistical or other data that illustrate differences between approaches, and that allow aggregation/disaggregation of information at different levels of granularity – individual student, class, grade, school, district, instructional approach, student characteristics, etc. These could be linked to particular instructional patterns, or they could be accessed and used as part of other efforts to improve instruction in schools, districts, etc.

Many of these technologies exist in some form today (Dede, 2000, pp. 15-16), but making them easily accessible to average teachers will require careful development work. For example, recording, editing, and publishing multimedia materials and examples from classroom practice in hypermedia format will allow the richness of instruction to be easily captured; providing teachers with more sophisticated user interface management systems will be necessary if the work is to be done in reasonable time; high bandwidth networks will be required to enable teachers in different locations, as well as teacher-educators and pore-service teacher education students, to access the materials thus created; software that supports computer-supported collaborative work will be critical if teachers are to see these tasks as shared professional responsibilities; the size of the files and databases created will require use of multiple read-write optical disk systems in conjunction with networks; and so on.

Examples of these approaches are seen in a few projects now under way. One of the best examples of this sort of organization of materials, records, video clips, and other items to document teachers' professional practice is discussed in Lampert and Ball's Teaching, multimedia, and mathematics (1998; see also DeMonner, 1998). The environment described here includes a special SuperCard application that allows users to interact seamlessly with such other applications as Netscape, ClarisWorks, and Adobe Acrobat:

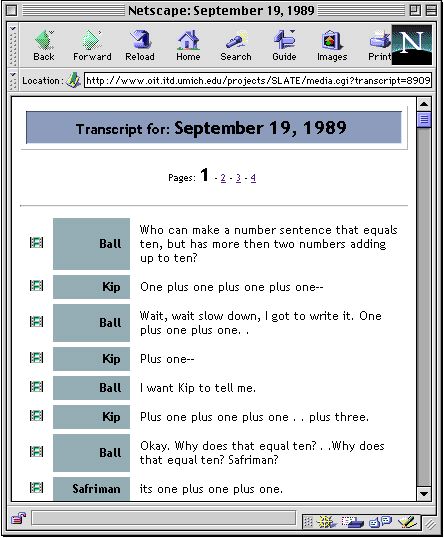

Individual session transcripts are cross-linked to video clips via the Web:

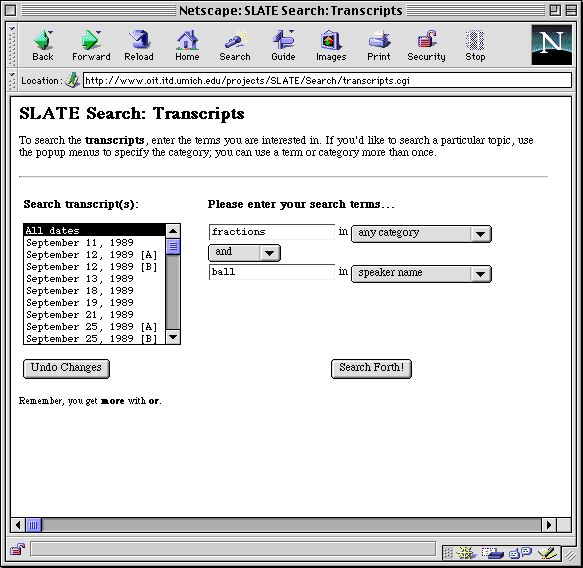

Users can query the system for particular types of information, and save the results as HTML documents:

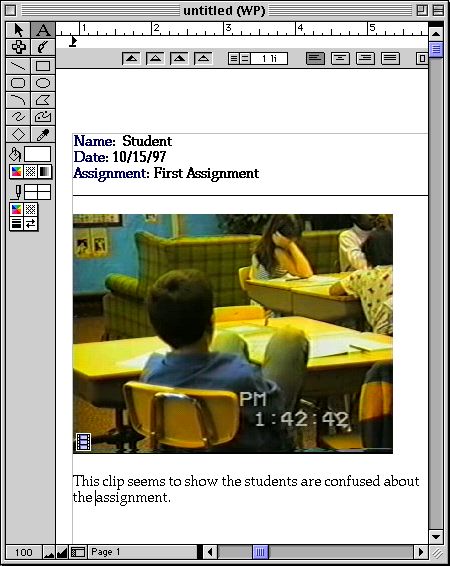

Students using the system take advantage of templates created in ClarisWorks, allowing drag-and-drop video editing, text editing, and graphics production:

Other types of materials provided by the system include digitized copies of student work, seating charts, and teacher journals.

A second example of multimedia in the service of virtual communities of practice is seen in the work of the Bridging Research and Practice group at TERC. Here, researchers and practitioners have prepared "videopapers" -- complex multimedia records of classroom experience. A videopaper typically includes: video of teaching sessions, examples of graphics prepared by students as a part of these sessions, written records of the dialogue accompanying the sessions, and commentary by participants and others on what happened. (See Carraher, Schliemann, & Brizuela, 1999, 2000; and Nemirovsky & Solomon, 2000).

Another example of the emergent form that virtual discussion of teaching can take is seen in the work of Janet Bowers and her colleagues (Bowers, Doerr, Masingila, & McClain, 1999). Here, the interface to a complex teaching case study is designed explicitly to encourage pre-service math teachers to engage in deep and focused exploration of how an exemplary math instructor's classroom "works." The interface looks like this:

Distinctive features here include videos of several days of classroom lessons, transcripts of the videos that advance as the video plays and that also contain embedded hypertext links to additional materials and samples of student work, lesson plans, seating charts of students in the classroom, as "issues matrix" that highlights pedagogical and mathematical issues that arise in the lessons, and a "floating notebook" that allows the user to make notes. Additional orienting features of the interface -- search functions for the video transcripts and bookmarking video segments -- encourage the user to cross-compare among examples.

These three examples, however, are mostly conceived of as cases to improve the work of pre-service teachers, rather than as in-progress works by practicing teachers. Moving to that level of everyday use will be the next step in this evolution of new virtual communities of professional practice.

Language learning: Where and how? Learning to "speak, read, and write" MuLTeaL would take some time in 2033, but not nearly as long as it takes the average teacher today to figure out how to edit HTML scripts, or to set up and become familiar with a major set of instructional programs. Practices urgently pressed upon groups of teacher education faculty in the hope their charges will become more computer-literate will need to be used here yet again – regular faculty at SCDEs would need to demonstrate these approaches in their own courses, labs would need to be well-equipped (or perhaps all the tools will be software based), as would clinical faculty. Use of MuLTeaLs would likely be especially welcomed by instructors in courses where it is critical to show interactions that can occur: different approaches to math and science teaching, for example, or teaching about diversity in different parts of the USA, or showing other teachers working with special needs students.

In teacher preparation, MuLTeaLs would need to be used extensively by both higher education faculty, clinical faculty, and cooperating teachers as a demonstration of how to bring technology to bear to improve professional development. Especially valuable would be their use for observation by supervisors, and the possibilities they present for cross-comment and analysis by other beginning teachers. Clinical faculty (teachers on short-term leave from local school districts and working in the teacher preparation programs of SCDEs) would also become extremely proficient in the use of MuLTeaLs, and would not only demonstrate their use but also encourage student teachers and demonstrate varied methods of using them. Regular faculty in higher education would similarly use them regularly as part of their teaching, and would be engaged in constant efforts to improve the languages themselves -- adding new ways of annotating or commenting on lessons, developing new ways to capture and show data, subjecting their own teaching to the hard discipline of analysis and comment by others.

Under this sort of model, work on assessment becomes a central element in teacher preparation, for teachers learn not only how to assess the work of their charges in the classroom, but also how to assess their own work: How to scrutinize it with an eye toward improvement, how to let go of feelings of "ownership" of particular approaches or strategies, if the data do not support their effectiveness, how to deal with varied sorts of data from varied sources, and how to present those data in various sorts of arrays so as to make them more meaningful and useful. In this effort, all the parties will need to be involved -- student teachers, higher education faculty, supervisors, cooperating teachers, and other school personnel. These relationships are further outlined and detailed by Means (2000, in this series). Of particular importance here are the links among teacher preparation (at both pre-service and in-service levels), the ways technology interacts with both models of instruction and models of assessment, the types of outcomes deemed important for both teachers and students, and how work towards desired outcomes is supported by the school environment.

Conceptual Issues in the Development and Use of MuLTeaLs

There are a number of conceptual issues involved in the introduction and development of MuLTeaLs. None of these is easy to deal with, as they are all deeply embedded in the practices of teaching as enacted by thousands of teachers daily. Nonetheless, technology makes it possible to think about the improvement of practice in new ways, and so old ways of conceptualizing the routines of daily life for teachers need to be subjected to new attention.

Breaking down teacher solitude: Some 25 years ago, Dan Lortie's Schoolteacher (1975) noted the "solo practitioner" as the model of teaching most commonly encountered. Other commentators and researchers since then have also observed that the preferred mode of practice for most teachers is to work alone; Judith Warren Little has written extensively about the problems that this creates for improving teachers' professional practice (Little, 1982, 1985, 1990). Comments on involving teachers in intense scrutiny of their own work typically note the difficulty the process presents for them, especially when it requires self-disclosure via video. Thus, the process of creating an interest and eagerness among teachers to engage in this sort of activity (or at least some substantial core cadre of them, so that the process could become something of a norm of practice) would take special effort. Incentives can play some role here, but ultimately the pressure must come from within the profession itself, just as it has begun to push recently for a more central role in the design of teacher education programs, in enabling reform efforts, and in managing schools through site councils.

Risking exposure: The bottom line here is simple; it is a claim that treating one's own instructional practice as experimental can lead to dramatically different -- better -- results for learners. Knowing whether this is in fact true will require a different pattern of behavior from educators, a pattern in which the exposure of one's own faults is taken as a given, and one's own practice becomes the object for experimentation and attention. There are other risks here -- that some teachers will be too flip, try too many different approaches, hide from accountability under the guise of experimentation. The links between experimentation and achievement must be established early on to avoid this problem. But, most importantly, we must find ways to encourage teachers not only to try new approaches, but also to document those using the kinds of technology that are now becoming available via broadband networks, improved software for image capture and manipulation, insertion of varied kinds of text and graphic commentary, and approaches for editing and distributing multimedia productions via the Internet. It is the documentation, the sharing, and perhaps most importantly, the cross-commentary on others' work that is most central here.

The State Policy Environment

What role is there for the state and the federal government in the process of creating and encouraging the use of the sorts of virtual communities of professional practice? What follow are some policy implications based on the foregoing description and analysis. It should be noted in advance that much of what is suggested here requires strong additional efforts from within the profession to move in the directions indicated in the immediately preceding section, especially the issues of braking down solitude and risking exposure. If these cannot be dealt with, the use of the approaches described here will necessarily remain limited to a few enthusiasts; if they can, the structure of teaching as a profession may shift in ways that will allow it to better support large-scale reforms.

Encourage virtual communities of professional practice. There must be straightforward encouragement to SCDEs and TEPs to create both the languages themselves, but perhaps more importantly the environments in which their use would make sense. In a traditional teacher education program, much emphasis is placed on the development of practical skills, some on the acquisition of particular knowledge deemed important by the schools and society (ability to deal with students from diverse backgrounds, information on legal aspects of education, and so on). There needs to be an outside source of encouragement to work toward the development of a common language that allows teachers to share the results of their work across settings; some of that can come from individual institutions, but more needs to come from the states and the federal government. For example, the State of California, in the final report of its Computer Education Advisory Panel (Final Report, 1998), devotes much space and attention to the use of technology as a tool to support student learning, and to its potential as a teacher productivity aid, but no mention is made of the possibilities of teachers using technology to exchange with one another information about their own teaching for professional development purposes.

Major technology organizations such as ISTE and the Milken Exchange put most of their emphasis on either student learning via technology, or on teacher learning to use basic technology and their Internet. (See, e.g., descriptions of the Academy for Technology Leadership; ISTE, 1999). In a 1999 report prepared by the Milken Exchange, only four states reported continuing education requirements pertaining to teachers' technology proficiency for certification maintenance or renewal (Lemke & Shaw, 1999, p. 6).

States wield a large stick with SCDEs and TEPs with regard to their accreditation and program approval. While there have been serious efforts in recent years to enhance TEPs through increased technology content, that effort has mostly been focused on acquaintance with computers, use of web-based materials in the classroom, and use of teacher productivity tools (gradebooks, e-mail, etc.) A deeper focus on encouraging the development of virtual communities of professional practice, on developing the language of intraprofessional communication, and on finding ways to encourage teachers to address each other, via technology, about their successes and failures in the classroom, will be important here. Obviously, the claim that such programs are effective in improving the quality of instruction should not be taken at face value -- careful assessment studies would also need to be promoted that would shed further light on the relationship among professional development, practice, and achievement. Ways of conceiving of such a model of change are outlined by Means (2000, in this series). Only if this set of connections can be well established would the significant costs implied by the scenario presented here be worth incurring.

Include technology-based professional communication in pre-service assessments of teacher preparation to use technology. One step toward teachers' broader involvement in the sort of virtual community of professional practice envisioned here would be through preparation and use of electronic teaching portfolios as a requirement in TEPs. Some programs, such as that at the University of Washington, currently offer pre-service teachers the opportunity to create such portfolios (Student Work, 2000). But the current portfolio format and requirements push and pull on the pre-service teacher from multiple directions; the needs are many: to complete program requirements and satisfy state standards, to present themselves well in using the portfolio as a job-search tool, and (perhaps) to begin to engage with peers in a intraprofessional community of practice. And as Means (2000, in this series) notes, at present "portfolios represent work products, not work process" (p. 11). Moving pre- and in-service teachers (and those who scrutinize their portfolios) away from that assumption, and towards a situation in which an electronic portfolio is seen as a "work in progress," will require careful effort. States could assist in this process by encouraging not only that SCDEs require electronic portfolios of pre-service teachers, but also that they design these to serve multiple purposes -- evidence of proficiency in technology use (the creation of the portfolio itself), as collections of technology-assisted (and other) instructional examples, and as vehicles for virtual exchange of professional information among professionals.

Work with relevant professional groups to support technology-based interchange for professional development. The kinds of changes in practice suggested here would also not be possible without the support of teacher unions at local and state levels. The link between observation and evaluation is well-established in teachers' minds, and so practitioners (whether classroom teachers generally, clinical faculty, or cooperating teachers) would be unlikely (and arguably unwise) to adopt the kind of self-critical approach to one's own work implied by MuLTeaLs without corresponding changes in the ways that local schools and districts think about teacher evaluation. Strong guarantees would need to be in place that teachers would not be held accountable for admitting problems and showing an experimental attitude toward their own practice.

The experience of Thompson et al. (2000, p. 11) with eCOMET illustrates that such a "risk-taking" approach to practice can emerge when supportive conditions are in place. Negotiation of provisions to encourage development of virtual communities of practice would become a routine part of bargaining at the local levels , and state-level organizations would also need to take a leading role in developing, encouraging use of, and improving the ways of capturing and sharing models of teacher practice via MuLTeaLs. And, of course, all of this proceeds in an environment already made more complex by the need to address, as part of professional development, the challenges of educational reform and implementation of standards (Stein, Smith, & Silver, 1999).

Provide incentives for teachers and LEAs to use technology collaboratively in the service of reform. One way to approach this complex set of issues would be for states to require districts to engage in multi-school comparisons of attempts to implement technology-based reform and meet new standards. Knowing that one's own school was to be compared to others in a district, based on very detailed analysis of data from individual classrooms, could provide a powerful impetus for interest in and a willingness to share information among teachers in that school or district. Doing this effectively would require states and districts to make available on-line large amounts of comparative data, so as to encourage teachers' curiosity about the conditions (especially instructional approaches) that lead to differing levels of success in different environments.

Offer teachers professional development opportunities sufficient to the complexity of the task. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, state and federal agencies could work toward improving the availability of time for educators to create, exchange, use, and learn from the kids of information that MuLTeaLs would make possible. Numerous studies have shown that teachers commonly feel pressed for time, and that time to engage in professional development efforts, even of the most prosaic kind, is a rarity for most teachers. Learning to use a MuLTeaL would be a significant time commitment for a teacher (at least at first, as the technology itself was developing), and using it on a regular basis would require time both to create one's own materials, and to comment on others' (an essential aspect of the process, if use is to become regular). Arranging and organizing teachers' work schedules so as to make this kind of professional effort feasible should be come a priority for local an state agencies charged to improve the quality of teaching and the enhancement of educational outcomes. In the long run, this sort of time for professional development may ultimately become more important for educators than reductions in class sizes.

Collect empirical support for the efficiacy of virtual communities of practice. It was noted above that there must be empirical support for the value of this sort of approach. No agency, no state, no federal government can invest in the substantial costs that development of MuLTeaLs would entail without significant evidence that their use made a difference in teaching. Perhaps it would not. But the strong suggestion from other professions is that practice, when subjected to careful attention buy concerned professionals other than oneself, improves. We need to document this for teaching, and if it holds here as well, we need to work carefully to provide the tools on a wide scale to allow teachers to talk among themselves about the elements of practice that work, and to approach their practice in new ways as a result. It may well be that this, in addition to the use of technology in support of classroom instruction with learners, represents a critical future impact of technology on education.

References

Becker, H. J. (2000). Findings from the Teaching, Learning, and Computing Survey: Is Larry Cuban right? Paper prepared for the Educational Technology Leadership Conference, Washington, DC, January 13-14, 2000.

Bowers, J., Doerr, H. M., Masingila, J., & McClain, K. (1999). Making weighty decisions: A case study of mathematics teaching and learning. Available online at URL:

http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/faculty/jbowers/overview.htm.

Carraher, D., Schliemann, A. D., & Brizuela, B. M. (1999). "Bringing out the Algebraic Character of Arithmetic" paper presented at symposium, Toward a research base for algebra reform beginning in the early grades, presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Montreal, Canada, April 21, 1999. Available online at URL: http://www.terc.edu/mathofchange/PAPERS/BRPAERAdoc.pdf

Carraher, D., Schliemann, A. D., & Brizuela, B. M. (1999). Bringing out the Algebraic Character of Arithmetic. Videopaper prepared for presentation at the Videopapers in Mathematics Education Conference, Dedham, MA, March 9-10, 2000.

Dede, C. (2000). Implications of emerging information technologies for states' education policies. Paper prepared for the Educational Technology Leadership Conference, Washington, DC, January 13-14, 2000.

DeMonner, S. (1998). SLATE: Space for Learning and Teaching Exploration. Available online at URL: http://soe.umich.edu/resources/techserv/slate/slate.htm.

Etzioni, A. (Ed.) (1969). The semi-professions and their organization: Teachers, nurses, social workers. New York: Free Press.

Final Report of the Computer Education Advisory Panel. (1998). California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. Report issued, July, 1998; adopted, December, 1998. Available on-line 12/99 at URL: http://www.ctc.ca.gov/CEAP/CEAP.html.

Firestone, W. A., & Pennell, J. R. (1997). Designing state-sponsored teacher networks: A comparison of two cases. American Educational Research Journal, 34(2), 237-266.

Frederiksen, J. R., Sipusik, M., Gamoran, M., & Wolfe, E. (1992). Video portfolio assessment: A study for the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Gamoran, M. (1994). Informing researchers and teachers through video clubs. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association.

ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education). (1999). The ISTE Academy for Technology Leadership: Mission and profile. Available on-line 12/99 at URL: http://www.iste.org/ProfDev/index.html

Lampert, M., & Ball, D. L. (1998). Teaching, multimedia, and mathematics: Investigations of real practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lemke, C., & Shaw, S. (1999, August). Education technology policies of the 50 states. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Exchange. Available on-line 12/99 at URL: http://www.milkenexchange.org.

Leonard, G. (1968). Education and Ecstasy. New York: Dell.

Little, J. W. (1982). Norms of collegiality and experimentation: Workplace conditions of school success. American Educational Research Journal, 19(3), 325-340.

Little, J. W. (1985, November). Teachers as teacher advisors: The delicacy of collegial leadership. Educational Leadership, 34-36.

Little, J. W. (1990). The persistence of privacy: Autonomy and initiative in teachers' professional relations. Teachers College Record, 91(4), 509-536.

Lortie, D. (1975). Schoolteacher: A sociological study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Means, B. (2000). Accountability in preparing teachers to use technology. Paper prepared for the Educational Technology Leadership Conference, Washington, DC, January 13-14, 2000.

Nemirovsky, R., & Solomon, J. (2000). "This is crazy. Difference of differences!" On the flow of ideas in a mathematical conversation. Paper prepared for Videopapers in Mathematics Education Conference, March 9-10, 2000, Dedham, MA.

Stein, M. K., Smith, M. S., & Silver, E. A. (1999). The development of professional developers: Learning to assist teachers in new settings in new ways. Harvard Educational Review, 69(3), 237-269.

Student Work -- Student portfolio sampling. (2000). A collection of student portfolios from the Teacher Preparation Program, College of Education, University of Washington. March, 2000. Available online at URL: http://depts.washington.edu/tepacct/

Thompson, A. D., Schmidt, D. A., & Stewart, E. B. (2000). Technology collaboratives for simultaneous renewal of K-12 schools and teacher education programs. Paper prepared for the Educational Technology Leadership Conference, Washington, DC, January 13-14, 2000.

What matters most: Teaching for America's future. (1996, September). Report of the National Commission on Teaching & America's Future. Kutztown Publishing Co., Kutztown, PA. Available at URL: http://www.tc.columbia.edu/~teachcomm/

Wilson, S. M., & Berne, J. (1999). Teacher learning and the acquisition of professional knowledge: An examination of research on contemporary professional development (pp. 173-209). In A. Iran-Nejad and P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Review of research in education. Vol. 24. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Wineburg, S., & Grossman, P. (1998, January). Creating a community of learners among high school teachers. Phi Delta Kappan, 79(5), 350-353.